Archaeopotamus, Boisserie, 2005

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00138.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/354487FC-FF8A-FFD9-FF61-3E32AD10F895 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Archaeopotamus |

| status |

gen. nov. |

GENUS ARCHAEOPOTAMUS GEN. NOV.

Description

Diagnosis: Hexaprotodont, characterized by having a very elongate mandibular symphysis relative to its width. This symphysis bears also an incisor alveolar process strongly projected frontally, very procumbent incisors, and canine processes poorly extended laterally and not extended anteriorly. The length of the lower premolar row approaches the length of the molar row. The horizontal ramus height is low compared to its length but tends to increase posteriorly. The gonial angle of the ascending ramus is not laterally everted.

Type species: Archaeopotamus lothagamensis ( Weston, 2000) , from Lothagam , Kenya, Upper Miocene .

Other material: Archaeopotamus harvardi ( Coryndon, 1977) ; Archaeopotamus aff. lothagamensis (Hex. aff. sahabiensis in Gentry, 1999); Archaeopotamus aff. harvardi (see below).

Etymology: ‘The ancient of the river’, to denote that this genus is for now the oldest recorded among wellidentified hippos, in a family closely linked to freshwater.

Geographical distribution: Lake Turkana basin ( Kenya); Baynunah Formation, Abu Dhabi (the United Arab Emirates); Rawi, Lake Victoria ( Kenya).

Temporal distribution: Mio-Pliocene, between 7.5 and 1.8 Mya.

Discussion

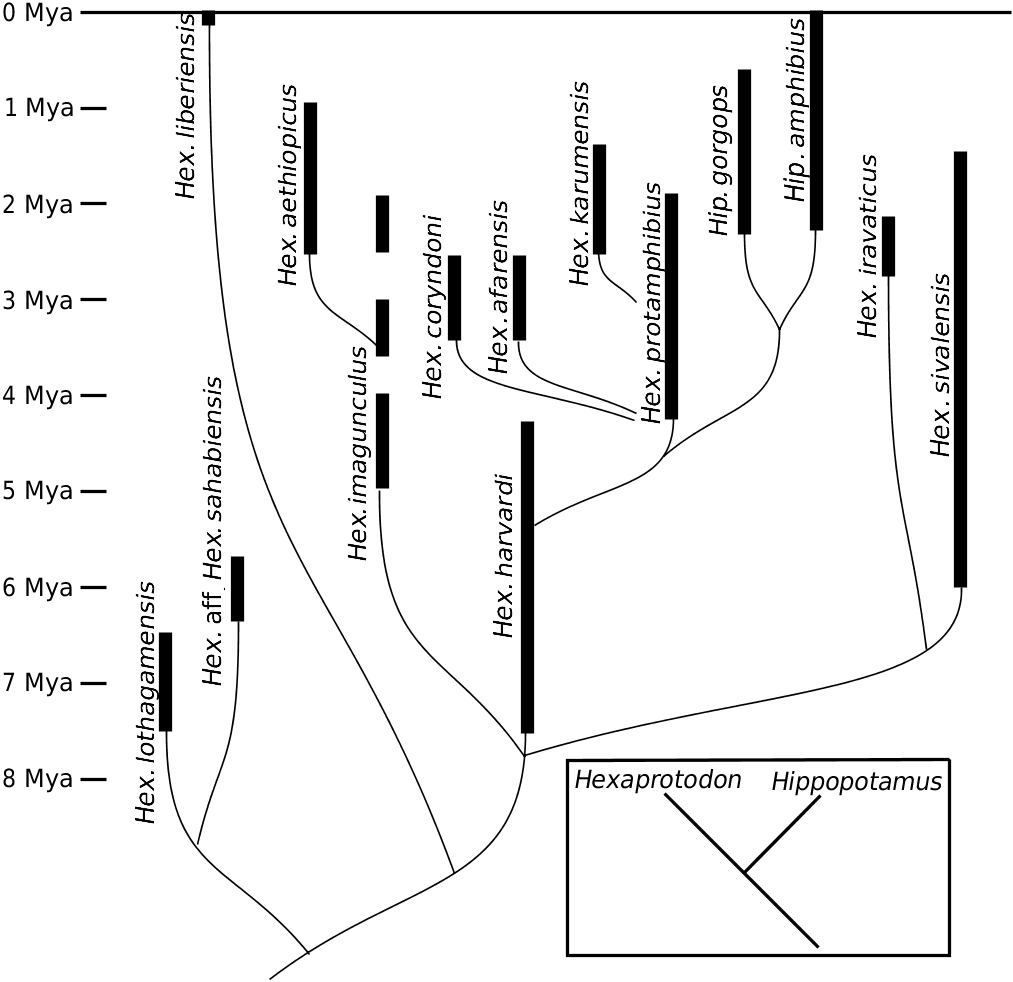

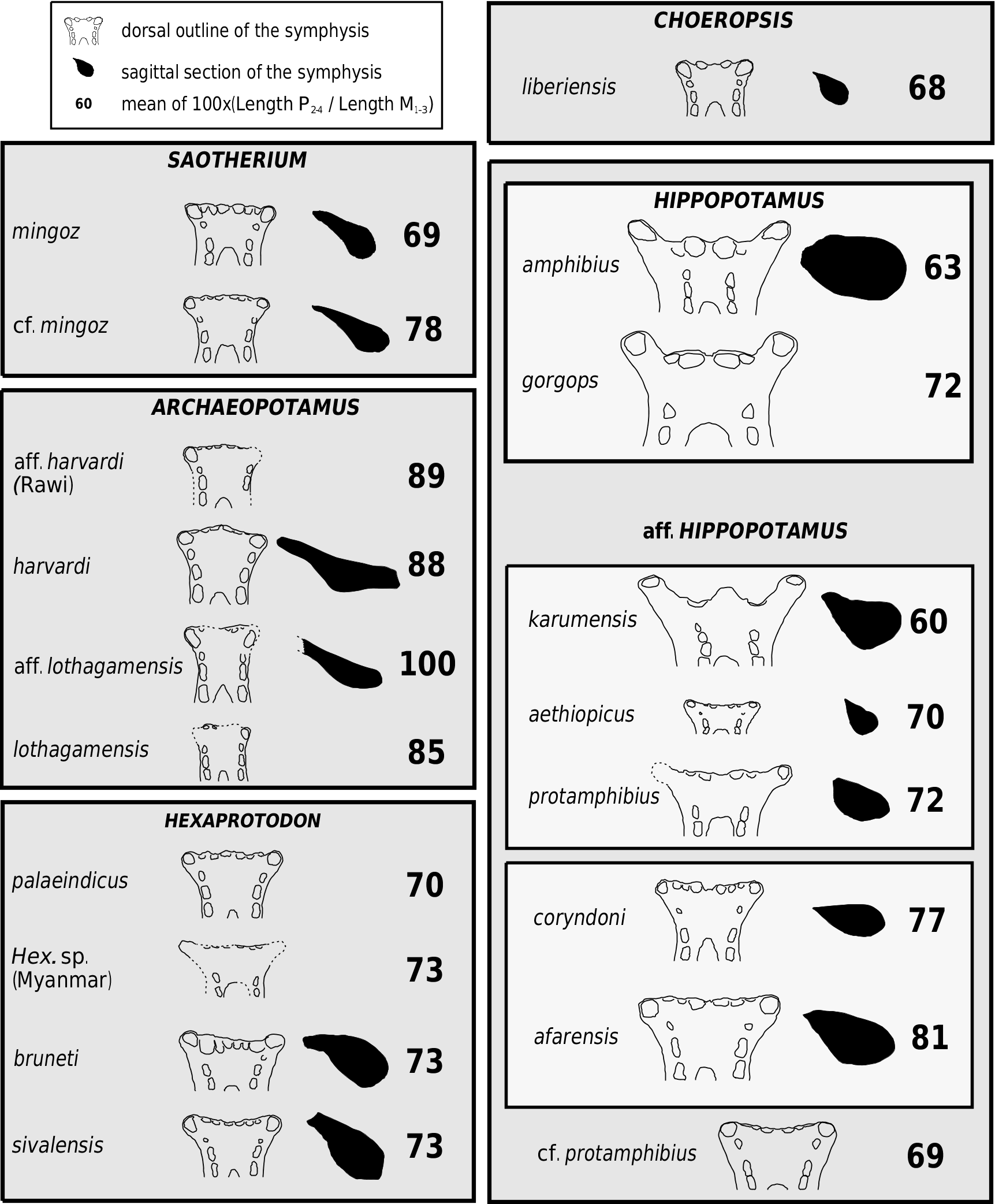

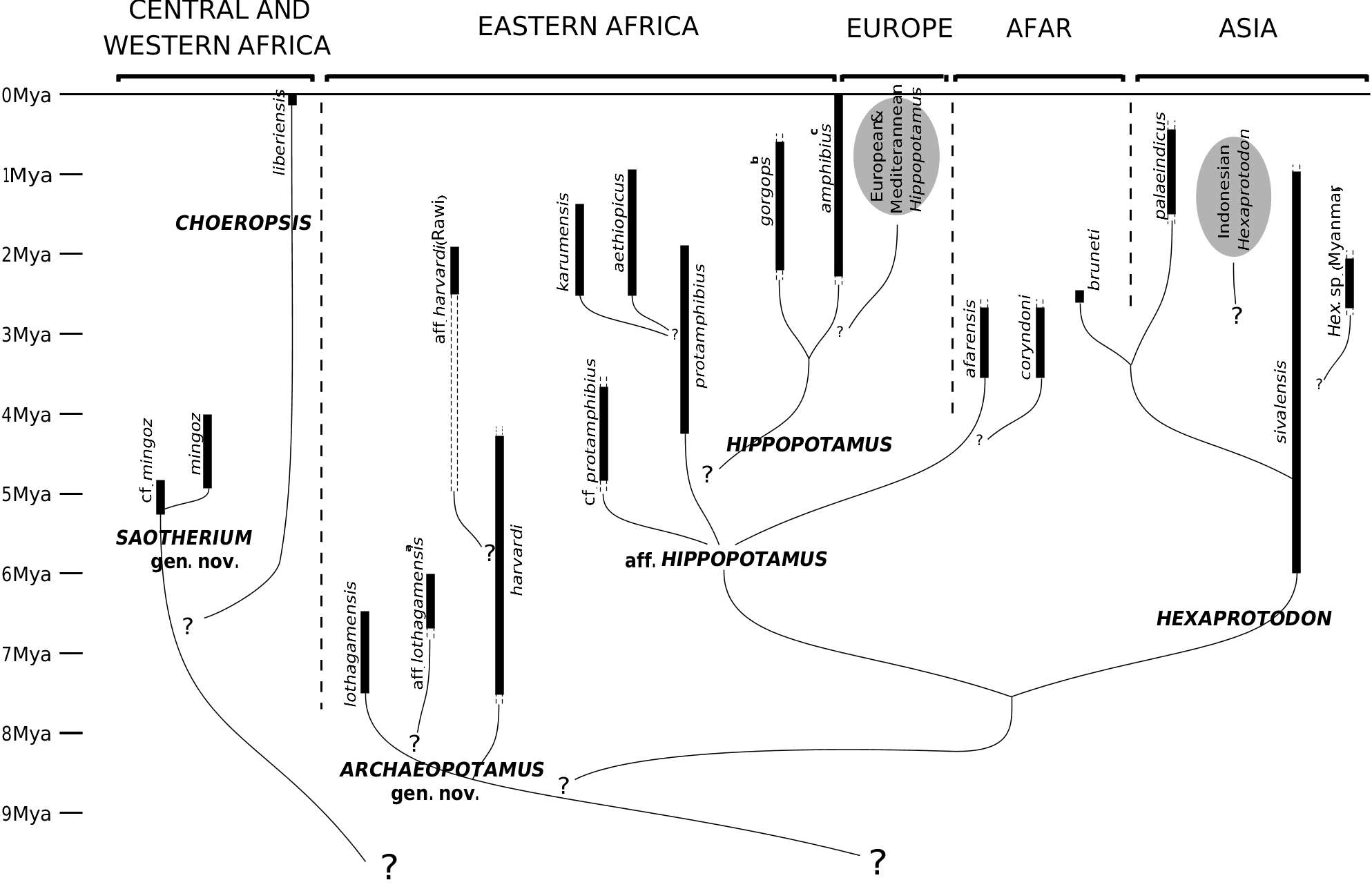

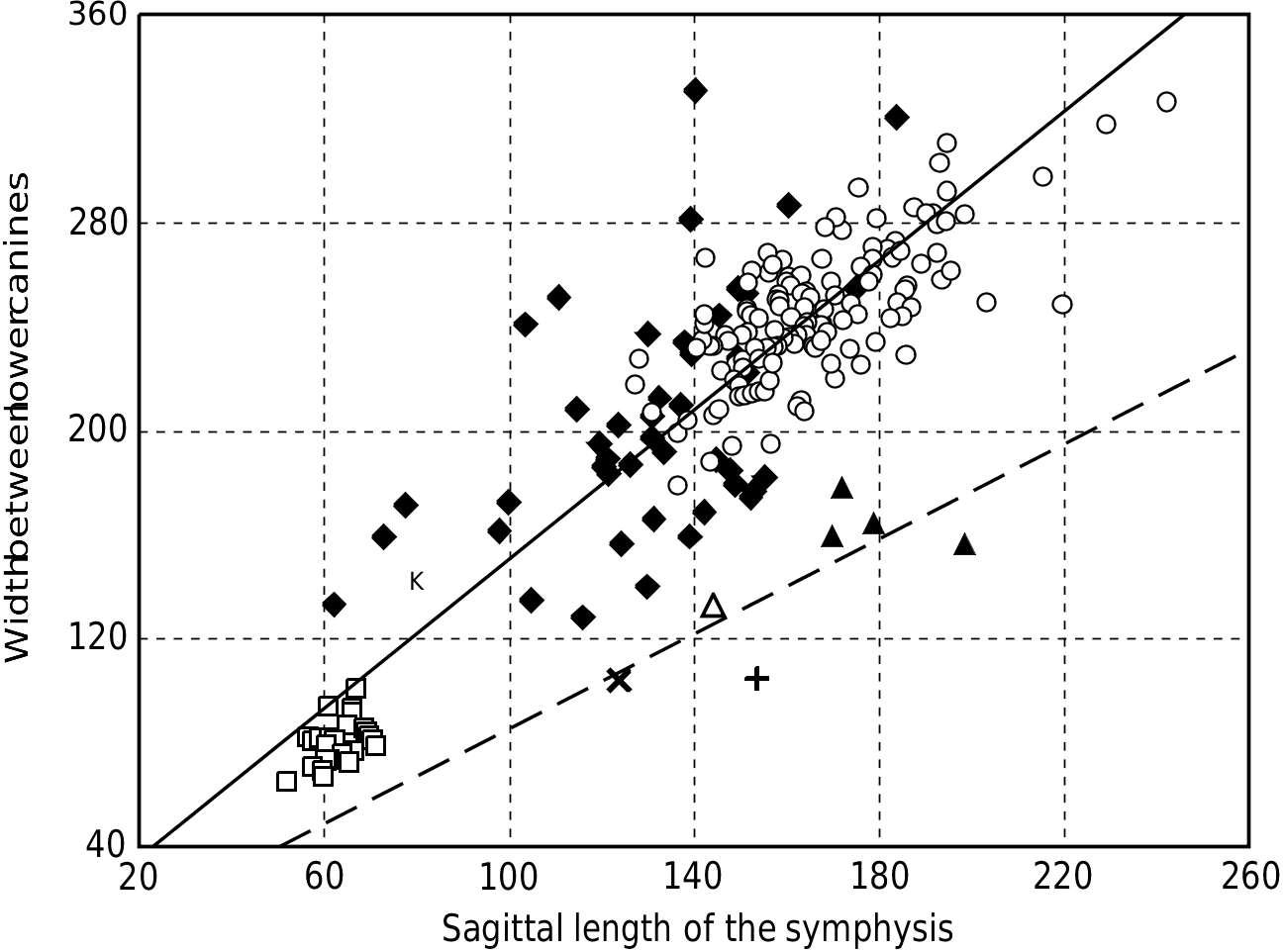

Two Miocene hippopotamids have been recently described from mandible elements: Hex. aff. sahabiensis ( Gentry, 1999) and Hex. lothagamensis Weston (2000) . These mandibles are characterized by their marked lengthening in the sagittal plane together with an almost negligible development of the canine processes, thus accentuating the generally narrow aspect of the symphysis. Weston (2000) indicated also that the small species lothagamensis could be an ‘ontogenetically scaled-down version’ of Hex. harvardi : it compares closely with the juvenile specimens of this larger species (see Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ). The biometrical study of the mandibular symphysis proportions confirmed the close relationship between Hex. harvardi , Hex. lothagamensis and Hex. aff. sahabiensis. As demonstrated in Weston (2000), they show a ratio of symphysis length vs. symphysis width that is strikingly different from the ratio seen in other hippopotamids ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ). There is one exception, this unusual ratio being also known for a mandible recovered at Rawi (Upper Pliocene strata of Kenya), purportedly related to Hex. imagunculus by Kent (1942). This mandible principally shows some anatomical affinities with those of the species harvardi (see remarks below). These hippopotamids are singular in that the gonial angles are not shifted laterally from the axes of the horizontal rami. Finally, the specimens present a relatively long premolar row P/1–P/4 as compared to the molar row M/1–M/3. The mean values of this ratio are lower in other species ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ).

Weston (2000) argued that elongate mandibular symphysis ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ) should be primitive within the family, the hippopotamids showing, in some cases, a trend toward shortening of the symphysis. It seems, however, that this opinion is based on the incidental fact that at the time the Lothagam hippos were the only well–known Miocene hippos and on the presumption that the Hippopotamidae derived probably from an animal having a narrow mandibular symphysis. Several comments are in order:

1. the immediate forerunner of the Hippopotamidae remains unknown, and hence the ancestral morphology is likewise unknown (the symphysis of Kenyapotamus is not sufficiently preserved to further elucidate this issue);

2. Choeropsis liberiensis and Saotherium , as described above, exhibit in many characters a cranial morphology still more primitive than that of Hex. harvardi (notably characters 7, 10, 13, 14), as well as having a shorter mandibular symphysis;

3. a newly recovered, well-documented hippopotamid (still under study) has recently been unearthed in Chad from a level probably contemporary with the lower Nawata Formation of Lothagam ( Vignaud et al., 2002), which also exhibits a symphysis shorter than in the hippos of Lothagam.

Hence, the adjective ‘primitive’ should be applied only with caution to the narrow mandibular symphysis of the Lothagam, Abu Dhabi and Rawi hippopotamids, even if this option cannot be discarded for now.

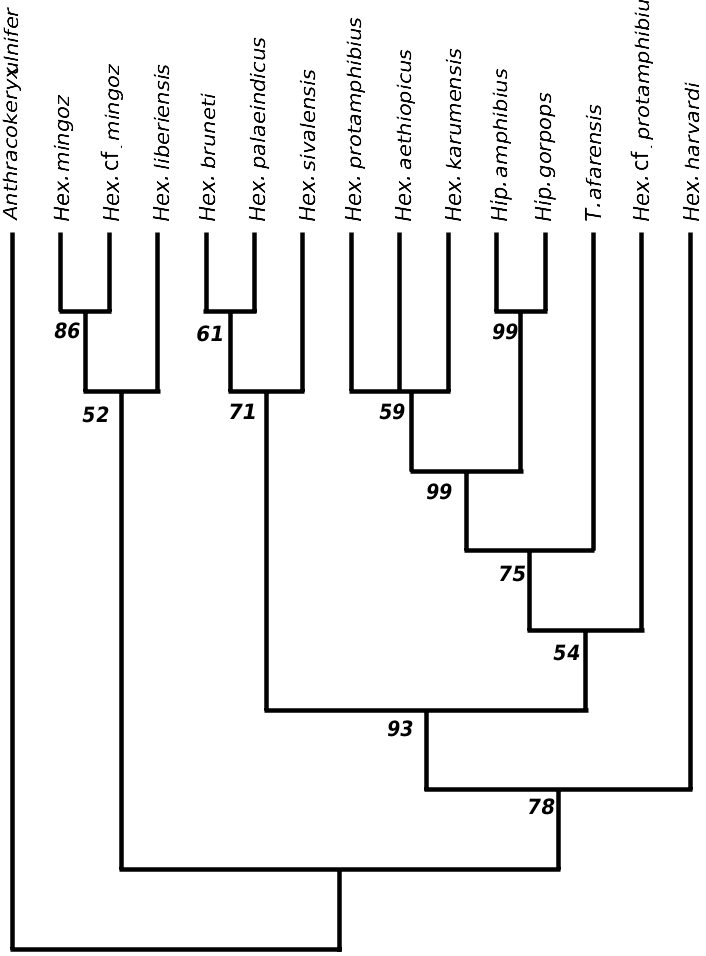

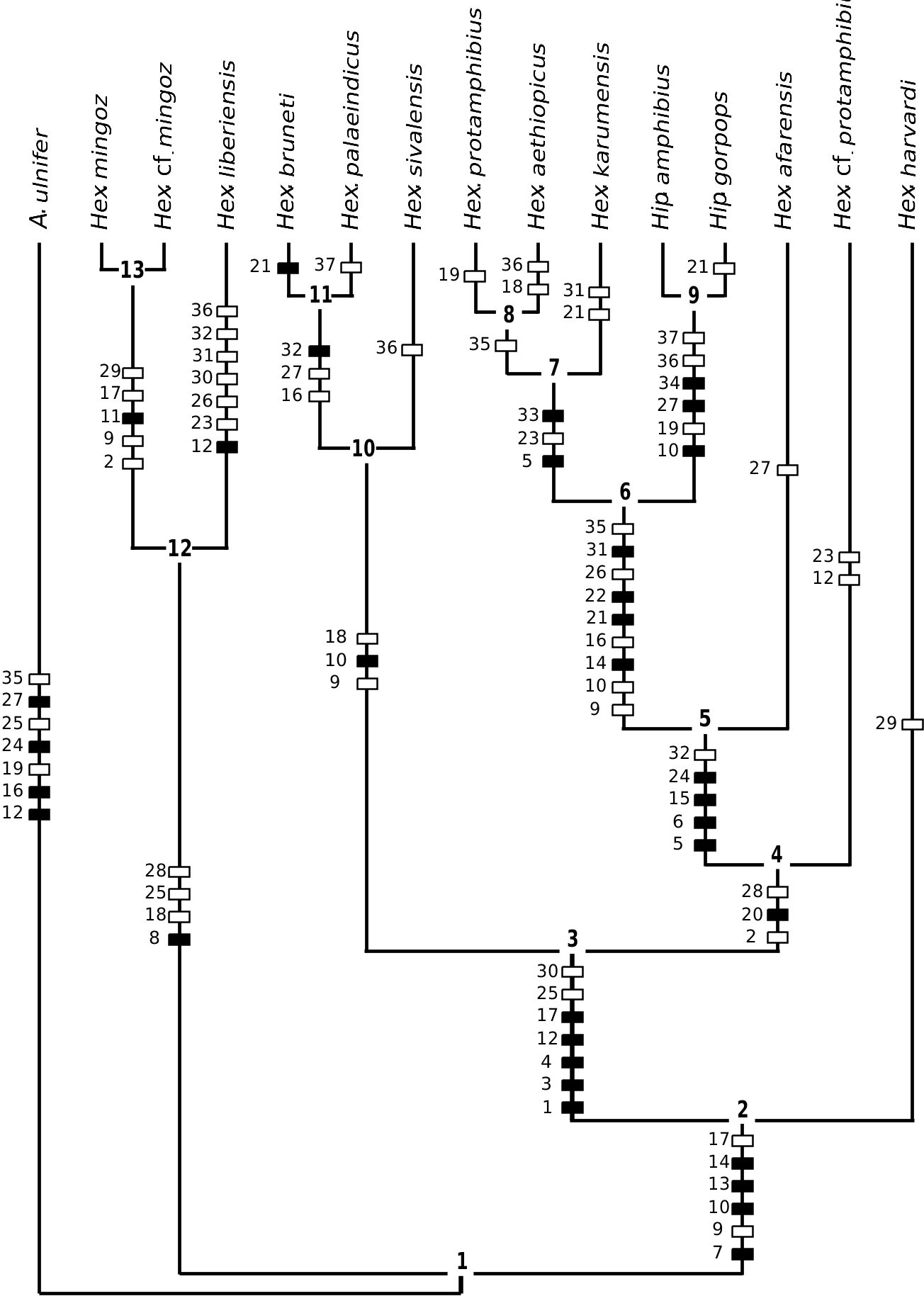

The fact remains that Weston’s (2000) phylogeny placed Hex. lothagamensis and the Abu Dhabi hippo into the sister group of all other hippos ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ), on shared mandibular morphology. Similarly, I propose here to include Hex. harvardi and the Rawi specimen in this same clade. This interpretation is also supported in a recent work ( Boisserie & White, 2004). Owing to the position of Hex. harvardi in the cladistic analysis ( Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 ), this clade, which might informally be called the ‘narrow muzzled hippos’ (after Gentry, 1999), might be the sister group of all other hippos, except of course Choeropsis and Saotherium ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). The great temporal range of harvardi and the late presence (at the end of the Pliocene epoch) of a related form in Rawi appears to indicate that the history of these narrow muzzled hippos constituted an important and distinctive, albeit peculiar, part of the family Hippopotamidae , in terms of its protracted duration and diversity. In order to acknowledge its importance, this clade is elevated here to the genus rank with the name Archaeopotamus .

Weston (2000) suggested that the Abu Dhabi form is more closely related to A. lothagamensis than to A. harvardi : the former two hippos share a canine cross section compressed from side to side and a P/4 with two main cuspids (lingual and buccal) of the same height. On the other hand, the canines of A. harvardi and the Rawi mandible show a less compressed section and their P/4s bear a more reduced and distal lingual cuspid. They differ also from A. lothagamensis and, particularly, from the Abu Dhabi hippo, in having a lower symphysis and the canine processes slightly more developed. However, A. lothagamensis differs from the Abu Dhabi material by its smaller size and some other features ( Weston, 2000). In the latter, the symphysis height and the oblique orientation of the incisors show some similarities to those of S. mingoz . Despite its similarities with A. harvardi , the Rawi mandible is too small and its I/2 too reduced in comparison to the I/1 to be included in this species. For these reasons, the Abu Dhabi material is denoted here as A. aff. lothagamensis , while the Rawi mandible is denoted A. aff. harvardi (see Figs 9 View Figure 9 , 10 View Figure 10 ).

Remarks: (1) When Gentry (1999) first described A. aff. lothagamensis , he called attention to certain resemblances to Hex. sahabiensis from Sahabi ( Libya), and thereupon proposed the designation Hex. aff. sahabiensis. However, the Libyan species is based on such fragmentary material that it appears difficult to ascertain on its position in the phylogeny (see below). Therefore, for the attribution of the Abu Dhabi hippo, it is more realistic to underline its resemblance to the small form of Lothagam. (2) In Weston (2000), Hex. crusafonti from localities of the Miocene (MN-13) of Spain was also considered related to A. lothagamensis and to A. aff. lothagamensis . However, as I have not yet seen these remains, I prefer to exclude them from consideration here.

GENUS HEXAPROTODON FALCONER & CAUTLEY, 1836 View in CoL

Description

Emended diagnosis: Hexaprotodont; characterized by a very high robust mandibular symphysis, relatively short in spite of its canine processes which are not particularly extended laterally; dorsal plane of symphysis very inclined; thick incisor alveolar process, frontally projected; some relatively small differences between the incisor diameters, the I/2 being usually the smallest; laterally everted but not hook-like gonial angle; orbit having a well developed supra-orbital process, and a deep but narrow notch at its anterior border; thick zygomatic arches; elevated sagittal crest on a transversally compressed braincase. Some constant features of this genus appear to be primitive: the strong double-rooted P1/ the quadrangular lachrymal, separated from the nasal bone by a long maxillary process of the frontal.

Type species: Hexaprotodon sivalensis Falconer & Cautley, 1836 , from Mio-Pliocene strata of the Siwalik hills, India / Pakistan .

Other material: In Asia, Hex. palaeindicus ( Falconer & Cautley, 1847) and the perhaps synonymous Hex. namadicus ( Falconer & Cautley, 1847), Hex. sp. indet. from Myanmar and the Indonesian hippos of Pleistocene age (see Hooijer, 1950); and in Africa, Hex. bruneti from Bouri, Afar, Ethiopia ( Boisserie & White, 2004).

Geographical distribution: Principal occurrences in the Indian subcontinent (see specially Lydekker, 1884; Colbert, 1935; Hooijer, 1950): Northern India and Pakistan, Central India, Nepal, Sri Lanka; in Myanmar ( Colbert, 1938); in Indonesia ( Hooijer, 1950); in Ethiopia, Afar depression ( Boisserie & White, 2004).

Temporal distribution: In Asia: end of Miocene in the Siwaliks (5.9 Mya; see Barry et al., 2002) to late Pleistocene in Central India and Indonesia; in Africa: only reported around 2.5 Mya.

Discussion

The central part of the consensus cladogram analysis ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ) comprises two clades: on the one hand, various East African hippopotamids and the genus Hippopotamus ; on the other, the three species sivalensis and palaeindicus of Asia, and bruneti of Ethiopia. This confirms a general consensus, established in the literature since the 19th century and persisting until now ( Falconer & Cautley, 1836; Lydekker, 1884; Colbert, 1935; Hooijer, 1950; Coryndon, 1978; Harrison, 1997; see also Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ), which recognizes one peculiar lineage of hipppotamids within Asia. The singular Hex. bruneti constitutes a presumptive migrant of this lineage into Africa ( Boisserie & White, 2004). This lineage evolved separately as early as the late Miocene, disappeared through extinction only quite recently, and exhibited noteworthy diversity (ten different forms having been recognized by Hooijer, 1950). Given the position adopted in this work with respect to Hippopotamidae systematics, this lineage must represent a genus. Its name must be that initially given to the species sivalensis : Hexaprotodon . Two comments are called for. First, the emended diagnosis of Hexaprotodon is for now based largely on a unique mandibular morphology, especially the high and robust symphysis relative to its other general dimensions ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ). Second, a feature commonly retained in the previous Hexaprotodon diagnoses, the deep posterior groove of the upper canine, has been superseded: in Hex. bruneti , the upper canine is antero-posteriorly compressed and the depth of this groove is attenuated, although it is still obvious and wide, and cannot be confused with the small groove seen in the genus Hippopotamus .

Evolutionary trends: Within this complex lineage, several evolutionary trends can be recognized, for example the increase of the I/3 diameter relative to that of the other incisors (culminating in Hex. palaeindicus and especially in Hex. bruneti ), the increasing elevation of the orbits ( Hex. palaeindicus ); and the increasing height of the molar crowns ( Hex. palaeindicus and Hex. sp. indet. from Myanmar).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Archaeopotamus

| Boisserie, Jean-Renaud 2005 |

HEXAPROTODON FALCONER & CAUTLEY, 1836

| Falconer & Cautley 1836 |