Leontopithecus caissara, Lorini & Persson, 1990

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5730714 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5730902 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DF668780-FFFD-FFEC-FADD-FBA9657CE358 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Leontopithecus caissara |

| status |

|

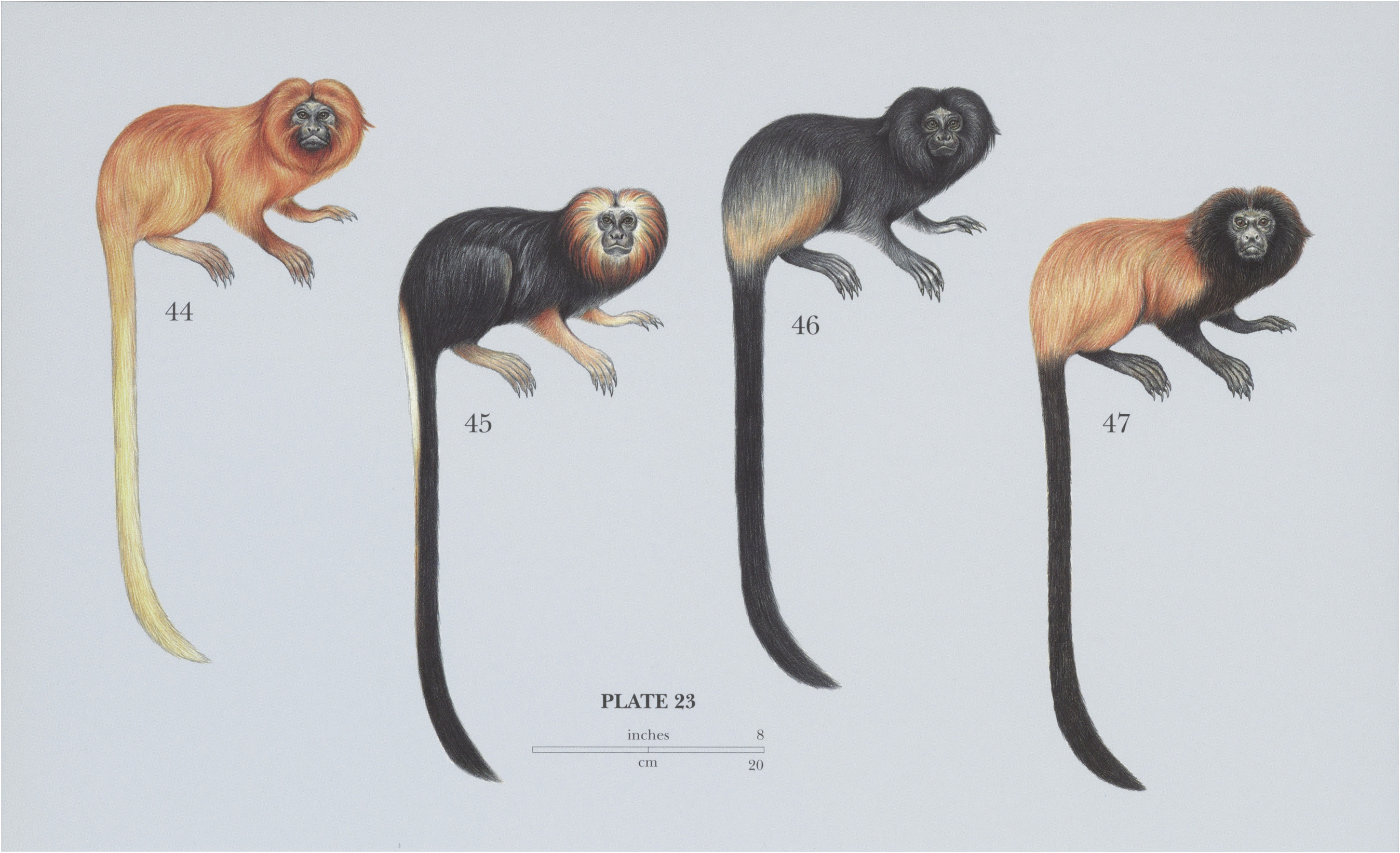

47 View On .

Black-faced Lion Tamarin

Leontopithecus caissara View in CoL

French: Tamarin-lion a téte noire / German: Schwarzkopf-Léwenaffchen / Spanish: Titi le 6n de cara negra Other common names: Superagti Lion Tamarin

Taxonomy. Leontopithecus caissara Lorini & Persson, 1990 View in CoL ,

Barra do Ararapira, Ilha de Superagui, municipality of Guaraquecaba, Parana State, Brazil (25° 18’ S, 48° 11°’ W).

The geographical proximity of L. caissara and L. chrysopygus and the finding that some captive L. chrysopygus show a pelage color pattern very similar to that of L. caissara led to the suggestion that L. caissara was a subspecies or mere color variant of L. chrysopygus . This was refuted by an analysis of the cranial and mandibular morphology by C. Burity and coworkers in 1999, which found L. caissara to be distinct. A molecular genetic analysis by B. Perez-Sweeney and coworkers in 2008 confirmed the conclusion of Burity, and placed L. caissara as a sister species to a clade comprising L. rosalia and L. chrysopygus . Monotypic.

Distribution. SE Brazil (states of Parana & Sao Paulo), on Superagti I, and on the mainland in parts of the valleys of the rios Sebui and dos Patos;its entire distribution is less than 300 km?®. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body c.34 cm,tail ¢.40 cm; weight 540-710 g. The body of the Black-faced Lion Tamarin is orange-gold, with black on the mane, face, chest,feet, forearms, and tail. The transitional region behind the shoulders consists of long golden hairs that are dark brown at the base.

Habitat. Mature lowland coastal forest. On the mainland and the island of Superagiii, Black-faced Lion Tamarins use swamp and inundated areas intensively because of their abundant foraging microhabitats and plants providing fruits and nectar. Dryland forest, however,is where they sleep in tree holes, Indaia palms ( Attalea dubia, Arecaceae ), and epiphytic bromeliads. Mainland groups, in particular, also use secondary forest because of their high densities of preferred fruiting trees. On the mainland, they avoid montane and submontane forest and are not found at elevations above 40 m. The Black-faced Lion Tamarin is the southernmost of any of the callitrichids, and changes in temperature and vegetation with elevation are more abrupt than at lower latitudes. Mountains come close to the sea in this region, and for this reason, their geographic distribution is very small. Middle and upper layers of the canopy are preferred.

Food and Feeding. Thefirst study of the Black-feaced Lion Tamarin indicated a diet of 745% fruits, 129% fungi, 10-3% animal prey, 1:3% gums, and 1% flowers and nectar. Thirty plant species in 17 families have been recorded in its diet. The principal family providing fruits is the Myrtaceae . Overall, nine species accounted for 94% of the plant part of the diet, 31% involving four species of Myrtaceae (Myrcia acuminatissima, M. multiflora, Marlierea tomentosa , and Psidium cattleianum). Tapirira guianensis ( Anacardiaceae ), Syagrus romanzoffiana ( Arecaceae ), Calophyllum brasiliense ( Clusiaceae ), and an unknown species of Myrsinaceae were also significant providers of fruits during the year. Nectar is taken from a number of species of Myrtaceae, Melastomatacae , and Bromeliaceae (Aechmea) . They eat flowers of Aechmea and Marcgravia polyantha ( Marcgraviaceae ), and gum of 1. guianensis is eaten occasionally. An interesting component of the diet is the sporocarp of the ascomycete fungus Mycomalmus bambusinus ( Clavicipitaceae ) that they find on bamboo culms (Chusquea) near the ground. Fungi are eaten in the dry season and early wet season in June—-October and particularly in July-September. Consumption offruit declines in the dry season (April-September). Animal prey include grasshoppers, cockroaches, stick-insects, beetles, insects, spiders, and tree frogs. They forage for animal prey from the ground to c.15 m in the forest canpoy but concentrate more effort at heights of 6-10 m.

Breeding. There is no information available for this species.

Activity patterns. Black-faced lion Tamarins begin their activities at 06:00 h and return to their sleeping sites at ¢.16:00 h. They are most active—feeding and foraging— in the morning at 09:00-12:00 h, after which they tend to rest more until ¢.15:00 h. They spend ¢.56% of their time moving, 29% feeding, 14% in social activities (mainly grooming), and only c¢.1% resting. On the island of Superagtii, they use mainly tree holes as sleeping sites, but on the mainland, they frequently use crowns of Indaia palms, bromeliads, and sometimes termite nests.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of the Black-faced Lion Tamarin are 3-7 individuals. Their home ranges are the largest recorded for any callitrichid. The average home rangesize for seven groups was 300 ha. They travel 1000-3400 m/day. Groups on the island of Superagtii tend to have longer daily movements indicating more dispersed food sources. On the mainland, two groups shared the same home range, with 100% overlap. With their large home ranges, densities are low and estimated at 1-7 ind/km?® on Superagiii.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Black-faced Lion Tamarin was first discovered in 1990 on the island of Superagti. In 2002, the total world population was estimated at less than 300 individuals. Currently, they are believed to number less than 400 individuals. Conservation and management of the Black-faced Lion Tamarin has been overseen by an international committee formed by the Brazilian government in 1992. The Brazilian government,in collaboration with the Instituto de Pesquisas Ecolégicas (IPE), has been carrying out conservation programs for the Black-faced Lion Tamarin since 1995. These activities included ongoing research on its ecology and behavior, management of the Superagui National Park, environmental awareness programs with schools and local communities, and programs to involve local fishing communities in conservation measures and to improve their livelihoods.

Bibliography. French et al. (2002), Holst et al. (2006), Kierulff, Raboy et al. (2002), Kleiman & Mallinson (1998), Kleiman & Rylands, (2002), Lorini & Persson (1990, 1994), Nascimento & Schmidlin (2011), Nascimento et al. (2011), Padua et al. (2002), Perez-Sweeney et al. (2008), Persson & Lorini (1993), Prado (1999), Prado & Valladares-Padua (2004), Prado et al. (2000), Rambaldi et al. (2002), Rodrigues et al. (1992), Rylands (1993c), Rylands, Kierulff & Pinto (2002), Rylands, Mallinson et al. (2002), Valladares-Padua & Prado (1996), Vivekananda (1994).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Leontopithecus caissara

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Leontopithecus caissara

| Lorini & Persson 1990 |