Leontopithecus chrysopygus (Mikan, 1823)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5730714 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5730900 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DF668780-FFF2-FFED-FA09-F78B6721E467 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Leontopithecus chrysopygus |

| status |

|

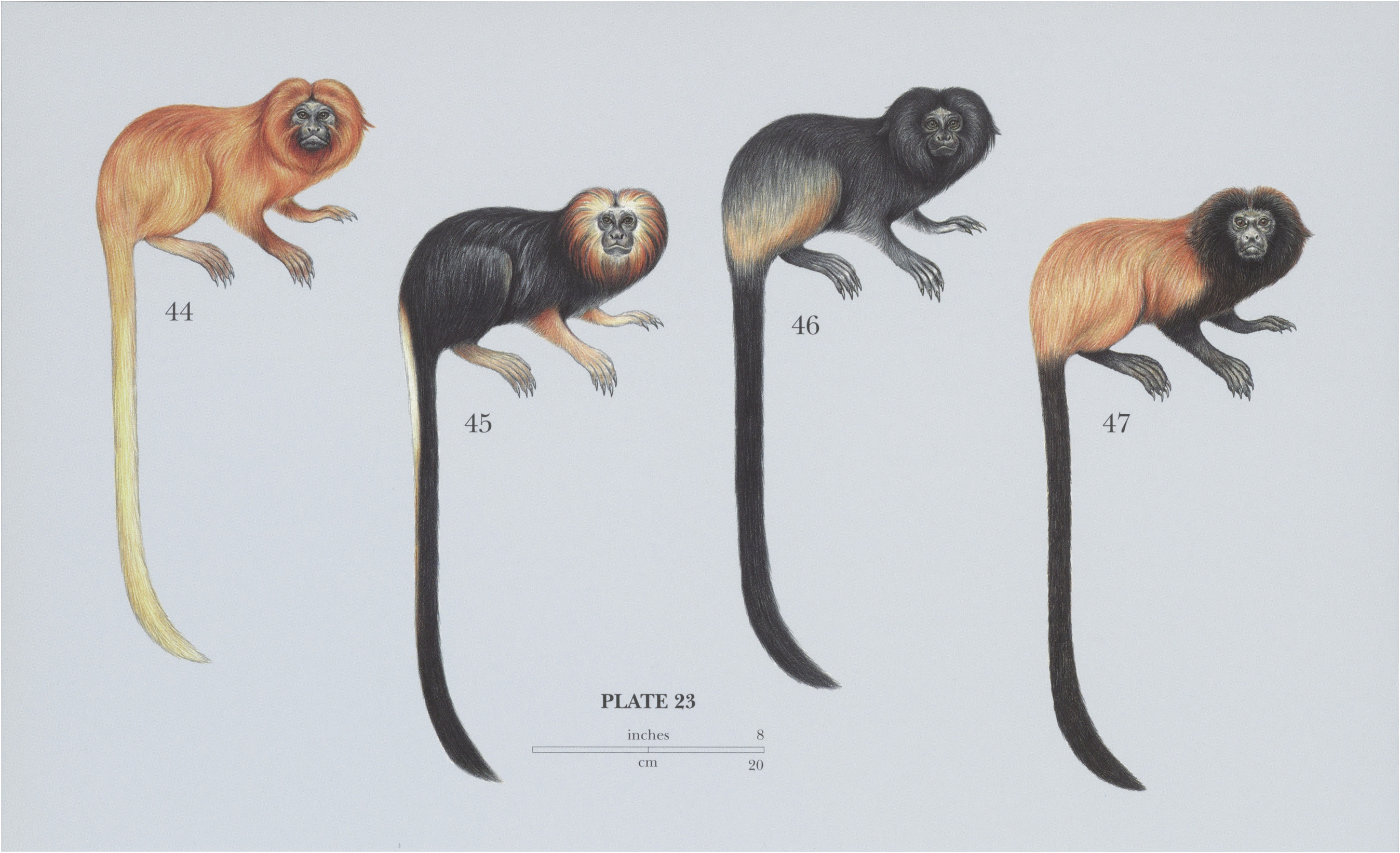

46 View On .

Black Lion Tamarin

Leontopithecus chrysopygus View in CoL

French: Tamarin-lion noir / German: Schwarzes Lowenaffchen / Spanish: Titi len negro Other common names: Golden-rumped Lion Tamarin

Taxonomy. Jacchus chrysopygus Mikan, 1823 ,

Ipanema (= Varnhagem or Bacaetava, near Sorocaba), Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Craniodental analysis of Leontopithecus by A. Rosenberger and A. F. Coimbra-Filho in 1984 found L. chrysopygus to be distinct in its larger size and more robust physique, and they suspected it to be the most primitive member of the genus. A molecular genetic analysis (mtDNA control region) by B. Perez-Sweeney and coworkers in 2008 found that L. chrysomelas was basal in the phylogenetic tree and L. chrysopygus and L. rosalia were derived sister species (also indicated in some craniodental aspects). Monotypic.

Distribution. SE Brazil ( Sao Paulo State), along the N (right) margin of the Rio Paranapanema, W as far as the Rio Parana, and between the upper rios Paranapanema and Tieté; today, known only from eleven widely separated forest patches covering c.444 km”. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 25-30 cm,tail 36—41 cm; weight 540-690 g. Male Black Lion Tamarins are larger than females. They are mostly black with golden-reddish patches on the forehead, rump, base of the tail, thighs, and ankles. The mane is long with a smattering of red-gold hairs.

Habitat. Inland, lowland mesophytic semi-deciduous forest, almost entirely lacking the bromeliads favored as foraging microhabitats by the coastal species of lion tamarins. Black Lion Tamarins particularly use swampy forest for their foraging and sleeping sites and the nectar provided in by Symphonia globulifera (Guttiferae) trees in the dry season. The middle and lower layers of the canopy are preferred.

Food and Feeding. Black Lion Tamarins eat fruits, nectar, gums, and small animals, mainly arthropods. Diets of four groups studied in Morro do Diabo State Park comprised 78% fruits, 14% animal prey, and 8% exudates (gums and nectar). Fruits and exudates came from 53 species in 24 families. Significant in the diets were the sticky soft mesocarp of the fruits of queen palm orjeriva ( Syagrus romanzoffiana, Arecaceae ), along with a remarkable preponderance of Myrtaceae (Campomanesia, Myrcia, Myrciaria, Myrceugenia, Eugenia, Psidium) that are abundant in the forests there. Small fleshy fruits of species of these genera ranked among the top ten items in the diets of the four groups studied and 65% of the fruits eaten overall. Fruit of Annona (Annonaceae) was also important, and they ate fruits of Rhipsalis (Cactaceae) and inflorescences of the epiphytic Philodendron (Araceae) . They ate the nectar of Mabea fistulifera ( Euphorbiaceae ) and gums of Helietta longifoliata, Esenbeckia (both Rutaceae ), and Acacia polyphylla ( Fabaceae ). Observations in the Caetetus Reserve found thatjust five species of plants provide nearly two-thirds of the fruit part of the diet through the year: Syagrus romanzoffiana ( Arecaceae ), Rhamnidium elaeocarpum ( Rhamnaceae ), Celtis pubescens ( Cannabaceae ), and two species of Ficus (Moraceae) . There, they also eat readily available gums of Tapiria guianensis ( Anacardiaceae ), Pilocarpus pauciflorus ( Rutaceae ), Terminalia (Combretaceae) , and Euterpe edulis (Arecaceae) . Animal prey includes Orthoptera (grasshoppers), phasmids (stick insects), beetles, caterpillars, cockroaches, spiders, snails, frogs ( Hyla ), lizards, snakes, and fledgling birds. As in the other lion tamarins, Black Lion Tamarins are site-specific foragers. They poke, probe, and search in dry palm leaves, twigs, and tree cavities and under loose bark. Lacking bromeliads as foraging sites in their native habitats, fronds, flowers, and leaflitter in crowns of palms are particularly important foraging sites; e.g. Syagrus romanzoffiana, guariroba (S. oleracea) and palmetto ( Euterpe edulis ). Sites used most for foraging in Caetetus Reserve were crevices and holes (36-43%) and palm crowns (20-23%), followed by bamboos, lianas, bark, and epiphytes. Black Lion Tamarins forage more for animal prey (19-8% of their time) in the dry season (March—-September) than the wet season (12:8%), and eat less fruit (59-4% vs. 94-3%) and more exudates (29-4% vs. 1-9%).

Breeding. Black Lion Tamarins breed once a year in the early wet season (October—February). Gestation has not been measured but is probably c.125 days, as in other members of the genus. Ovarian cycles average about 23 days.

Activity patterns. Black Lion Tamarins are active for about ten hours a day. They leave their sleeping site shortly after sunrise. Fruitfeeding is predominant in the early morning, after which they travel and forage almost constantly, with a lull to rest around midday. Fruit-eating peaks again in the afternoon before they retire. In a study of a group of Black Lion Tamarins in Caetetus Reserve, traveling accounted for 33-9% of their time, feeding 29-9%, resting 17-5%, foraging 15-8%, and 2-9% engaging in social or other activities. In the dry season when fruit is scarce, they travel more, rest less, and forage for animal prey more than in the wet season. At Morro do Diabo, Black Lion Tamarins consistently use holes in trees as sleeping sites. Of four groups studied there, each had 16-19 holes that they would use, generally not returning to the same one on consecutive nights.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group size is generally small, averaging 4-5 individuals (3-7), usually with a single breeding female and 1-2 adult males. Average home range size for four groups in the Morro do Diabo was 138 ha (range 113-199 ha). At Caetetus Reserve, the home range of a group of 4-6 individuals was considerably larger at 276-5 ha. This group initially had two adult females but one disappeared three months into the study, leaving a single breeding pair. The group at Morro do Diabo traveled 1362-2088 m/day. At Caetetus, a group traveled up to 3000 m/day. The most recent density estimate for the 34,156-ha forest in the Morro do Diabo indicated 3-7 ind/km? and a total population of over 1100. At Caetetus, small groups and large home ranges resulted in a low density of c.1 ind/km?*.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Black Lion Tamarin is threatened by loss of habitat through conversion to agriculture, cattle ranching, highways, and urbanization. Populations remaining today are small and occur in low densities (small groups with large home ranges). Even when protected, the principal problems for the eleven surviving populations are genetic and demographic. Much of their habitat was cleared by the early 1900s, and they were not seen for more 65 years. In 1970, a small population of ¢.100 individuals was discovered by Coimbra-Filho in Morro do Diabo State Park in the south-west of Sao Paulo State. By 1993, a total ofsix populations were known, totaling c.1000 individuals by 2002. Inbreeding, however, remains a problem for the Black Lion Tamarin, and its survival may ultimately depend on exchanging individuals among these widely scattered locales to maintain genetic diversity. Corridors have already been planted, and some translocations have been carried out. It is protected in Morro do Diabo State Park (34,441 ha of which 23,800 ha is forest), Caetetus State Ecological Station (2178 ha), and Mico-Leao-Preto Ecological Station (5500 ha) that includes three forest patches just to the west of the Morro do Diabo State Park. The Instituo de Pesquisas Ecologicas (IPE, founded by C. and S. Padua) set up the first field studies and conservation measures in the region of the Morro do Diabo in 1984, with the pending loss of part of the Park’s forest to the reservoir of the Rosana Hydroelectric Dam on the Rio Paranapamena. The principal measures underway to protect the Black Lion Tamarin focus on surveys (to monitor scattered populations and search for new ones), metapopulation management involving translocations and introductions, preservation of remaining forest fragments (with and withoutlion tamarins), and creation of corridors to link forest patchesto establish larger areas of continuous forest. Ongoing environmental education and awareness programs in the vicinities of protected areas embrace working with regional and local communities to improve their livelihoods, while instigating conservation measures protecting landscapes and natural resources. The captive population of the Black Lion Tamarin, initiated by Coimbra-Filho, founder of the Centro de Primatologia do Rio Janeiro, has never quite thrived as did those for the Golden and Golden-headed lion tamarins. A limited number of founders was one problem, and it was mitigated to some extent by rescuing Black Lion Tamarins during the inundation the Rio Paranapamena by the Rosana Hydroelectric Dam. Today, small healthy populations are maintained in a limited number of breeding centers and zoos in Brazil, Europe, and the USA, which are able to contribute to in situ metapopulation management protocols. Research and conservation measures for the Black Lion Tamarin have been overseen and guided by an international committee created by the Brazilian government in 1987. The total wild population has been estimated at ¢.1840 individuals in two genetically distinct populations: one in the eastern part ofits distribution, including Morro do Diabo, and the other in the western part, including Caetetus. The key to increasing the size of populations and demographic stability lies in forest restoration and creation of forest corridors between forest patches where they occur.

Bibliography. Albernaz (1997), Ballou et al. (2002), Burity et al. (1999), de Carvalho & de Carvalho (1989), Coimbra-Filho (1970a, 1970b, 1976, 1985a), Coimbra-Filho & Mittermeier (1973, 1977b), Cullen et al. (2001), Hershkovitz (1977), Holst et al. (2006), Keuroghlian & Passos (2001), Kleiman & Mallinson (1998), Kleiman & Rylands (2002), Mamede-Costa & Godoi (1998), Medici et al. (2003), Padua et al. (2002), Passos (1997, 1999), Passos & Keuroghlian (1999), Passos & Kim (1999), Perez-Sweeney et al. (2008), Pissinatti et al. (2002), Rosenberger & Coimbra-Filho (1984), Rylands (1993c), Rylands, Kierulff & Pinto (2002), Rylands, Mallinson et al. (2002), Valladares-Padua (1993, 1997), Valladares-Padua & Cullen (1994), Valladares-Padua, Ballou et al. (2002), Valladares-Padua, Padua & Cullen (2002), Wormell & Price (2001).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Leontopithecus chrysopygus

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Jacchus chrysopygus

| Mikan 1823 |