Leontopithecus rosalia, Linnaeus, 1766

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5730714 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5730896 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DF668780-FFF0-FFE3-FF3F-F7DC66AEE641 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Leontopithecus rosalia |

| status |

|

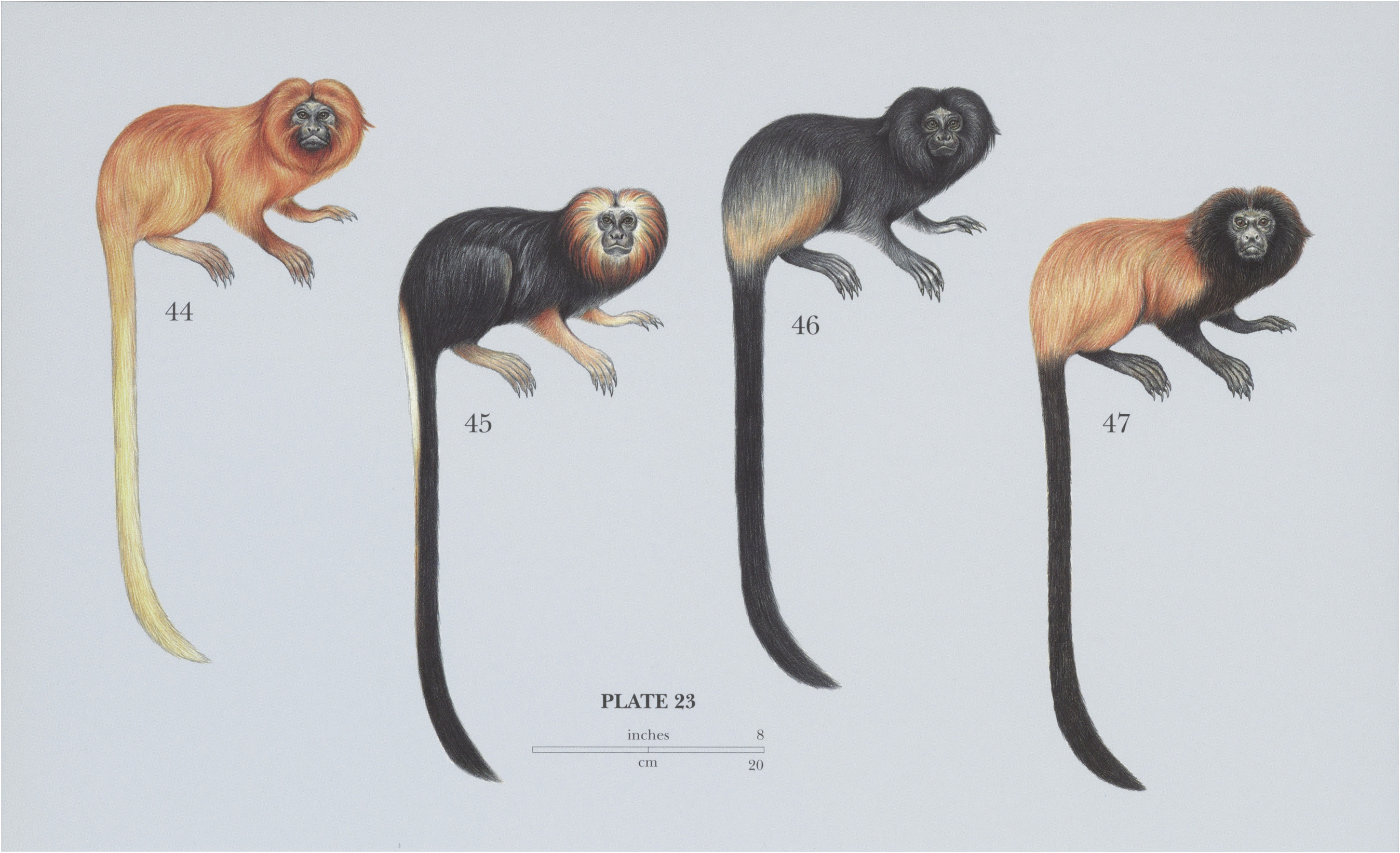

44 View On .

Golden Lion Tamarin

Leontopithecus rosalia View in CoL

French: Tamarin-lion doré / German: Goldgelbes Lowenaffchen / Spanish: Titi lebn dorado

Taxonomy. Simia rosalia Linnaeus, 1766 ,

Brazil. Restricted by A. P. M. Wied-Neuwied in 1826 to the coast between 22° S and 23° S, from the Cabo de Sao Tomé to the municipality of Mangaratiba, and further restricted by C. Carvalho in 1965 to the right bank ofthe Rio Sao Joao, Rio de Janeiro State.

Leontopithecus was formerly believed to comprise three subspecies ( rosalia , chrysomelas , and chrysopygus ), but a comparative study ofcraniodental morphologyin the genus by A. L.. Rosenberger and A. F. Coimbra-Filho in 1984 concluded that they are heterogeneous and individually distinctive with a non-clinal distribution of characters andthat the three taxa then known should be considereddistinct species. A comparative study oftheir long calls also confirmed the distinctiveness ofthe three species. Monotypic.

Distribution. SE Brazil (Rio de Janeiro State), originally the majority ofthe lowland coastal region ofthe State below elevations of 300 m; today largely restricted to two municipalities Silva Jardim and Cabo Frio. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 26-33 cm, tail 32-40 cm; weight 710 cm (males) and 795 g (females). The Golden Lion Tamarin is entirely covered by a coat of golden-orange with the exception oftheface, whichis naked and has a pale purplish tone. There is the occasional patch of orange, brown, or black coloration onthe tail and forepaws.

Habitat. Remnant primary and secondary coastal lowlandforest; occasionally reported from cultivated and secondary regrowth forest. The Golden Lion Tamarin prefers middle and upperlayers ofthe canopy, usually 3-10 m abovetheforest floor. Research onits ecology and behavior in the wild has been ongoing since 1983 in Poco das Antas Biological Reserve an isolated lowlandforest that is largely degraded with little mature old growth left. There, Golden Lion Tamarins prefer swamp (particularly for animal prey) and hilltop forest. Although their sleeping sites are often locatedin hillside forest, they otherwise tendto avoid these areas where foraging microhabitats such as palm crowns, bromeliads, and lianas are uncommon. In 1994-1997, Golden Lion Tamarins were successfully introducedin a forest just to the north in Uniao Biological Reserve; there the forest is better preserved and, as in Poco das Antas, Golden Lion Tamarins prefer swamp andlowland forest, abundant in lianas and bromeliads where they like to forage. They use hillside forest mostly for their sleeping sites.

Food and Feeding. Golden Lion Tamarins eat fruits (generally small, soft and sweet, black, purple, yellow, and red), nectar, gums, and small animals. At Poco das Antas, its diet is 78-4%ripe fruits, 5:6% unripe fruits, 1-5%nectar and gum, 13-6%animal prey, and 0-9%the milk of unripe Astrocaryum (Arecaceae) nuts. Nectaris eaten mainly from Symphonia globulifera (Guttiferae) that they find in the swampy areas but also Syzygium jambos ( Myrtaceae ). Species supplying gum include Anacardium occidentale ( Anacardiaceae ) and Mimosa bimucronata (Mimosoidae). They eat fruits from 63 species in 23 families. Diets of the Golden Lion Tamarins at Uniao were similar: 79-6% fruits, 15-4%animal prey, and 5% flowers and nectar; they used more than 97 species in 21 families. Despite the large numberofspecies found in diets at Uniao, only a few species accounted for the majority ofthe diet through the year. At Poco das Antas, 21 species accounted for 89%ofthe plant part ofthe diet of eight groups of Golden Lion Tamarins during a year ofstudy. At Uniao, seven species accounted for 56% of the feeding observations for a year: Miconia latecrenata ( Melastomataceae ), Sarcaulus brasiliensis ( Sapotaceae ), Cecropia (two species) and Coussapoa (Urticaceae) , Eugenia ( Myrtaceae ), and S. globulifera. Golden Lion Tamarins disperse a significant amount of seeds fromthe fruits they eat. At Uniao, seeds from 76 species overall (78%ofthe fruits in their diet) are ingested and defecated, most of them 10-200 m away from the parent plants. Regarding to animal prey, they forage principally for arthropods and small vertebrates in specific microhabitats, including tree bark, vines, leaflitter accumulations in the crowns ofpalm trees, and mostly epiphytic tank bromeliads, which collect leaves, debris, water, and a distinctive and abundant fauna between their leafaxils.

Breeding. Female Golden Lion Tamarins give birth to twins once, occasionally twice, a year. Mating occurs in August—March. Gestation is short compared with other callitrichids (125-132 days), and most births occur in September—November during the warm wet season when fruit is most abundant. Infants are carried constantly, and mostly by the mother, for the first three weeks, and for the majority ofthe time until eight weeks. By ten weeks ofage, they spend most oftheir time off the backs oftheir carriers. All group members carry young, and when young begin eating solid food, they provision them with food, particularly at 8-20 weeks old. Interbirth intervals are c.194 days, and the ovarian cycle is 18-19 days. Generally only one female breeds in each group, but non-breeding adult females show normal ovarian cycles. Reproductive inhibition ofsubordinate females by the dominant breeding female is behavioral and evidently not through suppression of ovulation, asis the case for marmosets and tamarins. Biannual monitoring ofsocial groups of Golden Lion Tamarins in Poco das Antas Biological Reserve has shown that ¢.70% of them have more than one adult male. In ¢.40% of the groups, these extra males are not sons or brothers of the breeding female and are potential breeders, indicating polyandrous mating on the part of the breeding female. The large majority of groups in the Reserve have only one breeding female, but in ¢.10% of groups, two females breed—mother and daughter in 75% of these cases. An incest taboo means that daughters do not mate with their fathers; when daughters breed, it is because their fathers have been replaced by another male or a second unrelated male has entered the group. Annual reproductive success of breeding subordinate females is lower (less than 50%) than that of the dominant female, and when the subordinate female is successful in bringing up her young, sheis typically the daughter of the dominant female. When a subordinate female becomes pregnant in groups where the only resident male is her father,it is suspected that the pregnancy results from a male in a neighboring group.

Activity patterns. Golden Lion Tamarins are active for c.10-11 hours/day. They become active and stay active longer in the warm rainy season when days are longer. In the cold dry season when both insects and fruit tend to be scarcer, they leave their sleeping sites later and return to them earlier. A year long study of eight groups at Poco das Antas showed that they spent 54-73% of their day resting or stationary, 8-23% eating fruit or plant exudates, 6-12% foraging for animal prey, 7-11% traveling, and 3-5% feeding on animal prey. At Uniao, Golden Lion Tamarins spent 32% of their time traveling, 40% resting and stationary, 9% eating fruit, 12% foraging for animal prey, and 7% in miscellaneous other activities. Differences among groups and between the two sites reflect differences in dispersion, abundance, and quality of foods and foraging sites. Golden Lion Tamarins in Uniao had a lower density and larger home ranges than in other areas. Much of the morning was spent feeding and traveling; they fed on fruit early in the day, and resting peaks occurred around midday. Tree holes (in living trees) are the preferred sleeping sites of all lion tamarins; in a 14-year record of sleeping site use by Golden Lion Tamains in Poco das Antas, 64% were tree holes, and tree holes accounted for ¢.85% ofsleeping sites used more than eight times by any group. Othersleeping sites include bamboo, vine tangles, and bromeliads.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Group sizes of the Golden Lion Tamarin are 2-11 individuals (average 5-4). Groups generally comprise a single breeding pair, and their offspring; groups as such are typically kin. Groups are quite stable, and immigration and emigration events are infrequent. At Poco das Antas, groups experienced an immigration event once every 2-9 years, on average. In 33% of these immigration events, more than one individual entered the group; in all these cases, these were males, and in most, brother duos or fathers and sons. Many of these immigration events follow the loss of one or both of the resident breeding adults. An individual joining, not replacing, adult breeding residents is very rare—once every eleven years on average, and they are nearly always dispersing males, not females. As such, groups of Golden Lion Tamarin have very limited immigration. Lone individuals and singlesex groups are driven away when they approach stable family groups. By three years of age, 60% of the offspring emigrate and only 10% remain in their natal group to four years of age. Most of those that remain become the resident breeder in the group. Females disperse when they are about two years old, males a little later at about two years and three months. Males often move into neighboring groups and situations where they have the potential to breed, which is rarely the case for females. Females become floaters and evidently suffer a higher mortality when dispersing. With more than one adult male, groups are potentially polyandrous, but it is believed that one dominant male monopolizes paternity. Home ranges of Golden Lion Tamarins at Poco das Antas were 21-73 ha (average 45 ha). The relatively high density at Poco das Antas—12 ind/ km? (2 groups/km?*)—is believed to be near or at saturation. With a density of 3-5 ind/ km? (0-5 groups/km?), the introduced population at Uniao (groups translocated from other parts of the species’ distribution) has larger home ranges, 65-229 ha (average 150 ha). Daily movements in the two forests reflect different home range sizes, 1339 m/day on average in Poco das Antas and 1873 m/day in Uniao. Itis possible that groups in Uniao will occupy smaller home ranges as the population increases, but the difference may also reflect variation in distribution and abundance of food resources.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Golden Lion Tamarin is threatened by widespread historical loss of habitat through conversion to agriculture, principally cattle-ranching, and urbanization. Alerted to their rapid decline by A. F. Coimbra-Filho in Brazil and R. A. Mittermeier internationally, a historic meeting was held in 1972 in the National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, called “Saving the Lion Marmoset.” This meeting resulted in the establishment of an effective, exemplary, captive management program by D. G. Kleiman, and eventually the launching of the Golden Lion Tamarin Conservation Program in 1983, which comprised a spectrum of conservation initiatives including captive (Kleiman) and long-term field research (J. Dietz), management of the Poco das Antas Biological Reserve created for the species in 1974 through the efforts of Coimbra-Filho and A. Magnanini in 1968, reintroduction of captive bred lion tamarins (B. Beck), and an environmental education program for the region (L. A. Dietz). The program was a partnership of the National Zoological Park, Centro de Primatologia do Rio Janeiro (CPR]J), and thefirst conservation non-governmental organization in Brasil, Fundacao Brasileira para a Conservacao da Natureza, Rio de Janeiro. From 1984 to 2000, 159 lion tamarins were introduced initially in the Poco das Antas reserve and later into privately owned forest patches in the vicinity. More than 100 zoos were involved, and after 21 years, descendants of captive Golden Lion Tamarins total 589 individuals in 87 groups. In 1991-1992, C. Kierulff carried out a population survey through the entire distribution of the Golden Lion Tamarin and estimated a population of 1000 individuals in 154 km? of forest. After locating twelve isolated and threatened groups in nine localities from 1994 to 1998, Kierulff translocated six of the groups (43 individuals) to an unoccupied forest that is now Uniao Biological Reserve. In 2006, the population at Uniao was more than 220 individuals in 30 groups, and more than 200 births were registered in twelve years. The most recent population estimate for the Golden Lion Tamarin (2008) was 1600 individuals. From the inception, the work was guided by an international conservation and management committee, created in 1981 for the management of the global captive population, but subsequently it was endorsed and is now managed through the Brazilan government to encompass all conservation and research initiatives for the Golden Lion Tamarin. Today, conservation is lead by the Golden Lion Tamarin Association (“Associacao Mico-LLeao-Dourado”) based in the Poco das Antas reserve, and its present challenges include increasing the forest available for the species and managing the widespread presence of introduced marmosets, the Common Marmoset ( Callithrix jacchus ) and the Black-tufted-ear Marmoset ( C. penicillata ). Densities of these hardy marmosets are higher than Golden Lion Tamarins in the forests they invade, and they are a threat through competition and, potentially, disease transmission. The greatest imminent threat is the expansion of a population of Golden-headed Lion Tamarins ( L. chrysomelas ), introduced into a forest patch in the suburbs of Niteroi (first noticed in 2002). In 2009, they numbered 107 in 15 groups and were found only 50 km from where the Golden Lion Tamarin occurs. A major program is underway to capture them because they could displace or hybridize with Golden Lion Tamarins.

Bibliography. Baker & Dietz (1996), Baker et al. (2002), Bales et al. (2001), Ballou et al. (2002), Bridgewater (1972), Brown & Mack (1978), Coimbra-Filho (1969, 1977, 1981), Coimbra-Filho & Mittermeier (1973, 1977b), Franklin et al. (2007), French & Stribley (1985), French, Bales et al. (2003), French, De Vleeschouwer et al. (2002), French, Pissinatti & Coimbra-Filho (1996), Hankerson et al. (2007), Hershkovitz (1977), Holst et al. (2006), Kierulff (2000, 2010), Kierulff & Procépio de Oliveira (1996), Kierulff & Rylands (2003), Kierulff, Procépio de Oliveira et al. (2002), Kierulff, Raboy et al. (2002), Kierulff, Ruiz-Miranda et al. (2012), Kleiman & Mallinson (1998), Kleiman & Rylands (2002), Kleiman, Beck et al. (1986), Kleiman, Hoage & Green (1988), Lapenta & Procopio de Oliveira (2008), Lapenta et al. (2003), Miller & Dietz (2005), Padua et al. (2002), Peres (1989a, 1989b), Perez-Sweeney et al. (2008), Pissinatti et al. (2002), Procépio-de-Oliveira et al. (2008), Rambaldi et al. (2002), Rapaport & Ruiz-Miranda (2006), Rosenberger & Coimbra-Filho (1984), Ruiz-Miranda, Affonso et al. (2006), Ruiz-Miranda, Beck et al. (2010), Rylands (1993c), Snowdon et al. (1986), Tardif, Santos et al. (2002).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Leontopithecus rosalia

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Simia rosalia

| Linnaeus 1766 |