Ateles chamek (Humboldt, 1812)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5727205 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5727284 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/313A8814-2A1C-F327-FA5D-F9C56612FA15 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Ateles chamek |

| status |

|

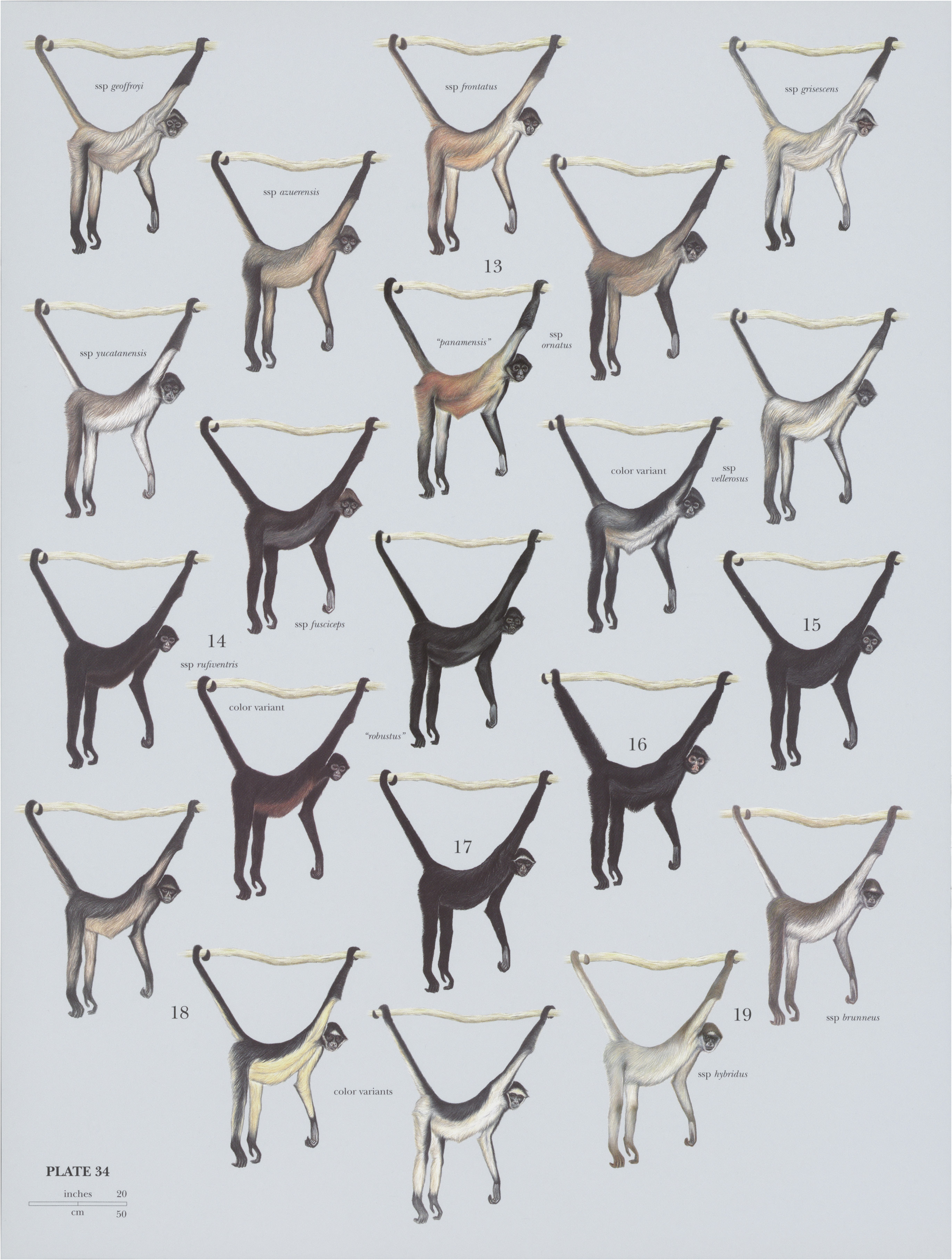

15 View On .

Black Spider Monkey

French: Atéle a face noire / German: Schwarzgesicht-Klammeraffe / Spanish: Mono arana negro Other common names: Black-faced Black Spider Monkey, Chamek Spider Monkey, Peruvian Spider Monkey

Taxonomy. Simia chamek Humboldt, 1812 View in CoL ,

Peru. Restricted by R. Kellogg and E. Goldman in 1944 to the Rio Comberciato, affluent of the Rio Urubamba, Cuzco, Peru.

Hybridization reportedly occurs with A. belzebuth in a restricted zone south of the Rio Maranon in Peru, and there is also a zone of apparent interbreeding with A. marginatus on the east bank of the upper Rio Tapajos, in Brazil. Monotypic.

Distribution. Amazonian Brazil, S of the Rio Amazonas-Solimoes, W of the rios Tapajos-Teles Pires to the Rio Ucayali in NE Peru (where it is replaced by A. belzebuth on the left bank of the lower Ucayali); it crosses the middle Ucayali S of the Rio Cushabatay (a left bank tributary of the Ucayali), extending to the interfluvium of the rios Ucayali and Huallaga, then S along the Cordillera Oriental, and into N & C Bolivia S to ¢.17° S, and from there, NE through Noel Kempff Mercado National Park. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 45-60 cm (males) and 40-52 cm (females), tail 80- 88 cm (males) and 70-80 cm (females); weight ¢.7 kg (males) and c.5 kg (females). The Black Spider Monkey is similar to the Red-faced Black Spider Monkey (A. paniscus ) in overall appearance but slightly smaller and shorter-haired, with largely black facial skin. Older individuals have some depigmenation around the eyes. Fur of adults is entirely black, except for a silvery genital patch and, sometimes, a few white hairs on muzzle, cheeks, and forehead. Infant Black Spider Monkeys have whitish skin around their eyes, pink feet, and sparse fur that appears grayish.

Habitat. Primary lowland terra firma rainforest, lowland subtropical semi-deciduous forest, and riparian and flooded forest. In Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Black Spider Monkeys are observed most often in tall forest but also in “saternejal” forest along the forest-savanna border, in the vicinity of small forest streams, that suffers periodic flash floods. They are found in transitional forest (forest to savanna) in southern Rondonia, Brazil. At Bolivia's Beni Biological Station and Biosphere Reserve, they are restricted to high forest.

Food and Feeding. Black Spider Monkeys have been studied in Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Lago Caiman in Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, and La Chonta and Guayaros forest reserves in Bolivia. At Lago Caiman, R. Wallace recorded a diet of 85-8% fruit, 10-7% flower buds and flowers, and the remainder items such as invertebrates, leaf galls, bark, and fungi. Seventy-eight plant species from c.31 families made up the diet. Fruit made up more than 70% of the diet in all but one ofthe eleven months of the study (63% in July at the end of the dry season). Important species providing fruits included Ampelocera ruizii ( Ulmaceae ), Spondias mombin ( Anacardiaceae ), Ficus americana ( Moraceae ), two species of Brosimum (Moraceae) , and the palm Euterpe precatoria. Black Spider Monkeys ate seeds of a few species in unripe fruits, particularly non-fleshy fruits, in the dry season—believed to be an important source of protein. In a year-long study by A. Felton and coworkers at La Chonta, fruits made up 82% of the diet, leaves 13% (buds and young leaves), and flowers 4:7%; the remainder was palm hearts, rotting wood, aerial roots, stalks, and bark. The plant part of the diet consisted of 63 species from 37 families; Moraceae was the most important in terms of number of species and time spent feeding (61:2% of the feeding records). They also ate caterpillars on leaves of Terminalia oblonga ( Combretaceae ). Fruits of Ficus boliviana and FE trigona, flowers and flower buds of Pseudolmedia laevis (all Moraceae ), and fruit of a species of Myrciaria ( Myrtaceae ) comprised almost 50% of the feeding records throughout the year. Lipid-rich fruits of Virola sebifera (Myristicaeae), although scarce, were highly favored. In 98% ofall fruit feeding events, seeds were ingested whole and defecated; seeds of palm fruits were spat out. Fruit and figs comprised more than 70% of the diet in all months except June (53%), and they ate both ripe and unripe fruits. Ripe and unripe figs (unripe particularly from F boliviana rather than F trigona) were a staple item throughout the year. Black Spider Monkeys preferred ripe figs to other ripe fruit, and unripe figs were eaten even when ripe figs and fruit of other species were available. Unripe figs were apparently selected because they were nutritionally rewarding for their proteins and lipids. At Manu in the diverse forests of the western Amazon, the diet for three months in the dry season was ¢.80% fruit, c.17% leaves, c.2% flowers, and c.1% leaf petioles.

Breeding. Births of Black Spider Monkeys at Manu occur throughout the year, but there is a peak in the early wet season. Infant survivorship up to one year old has been estimated at 67%. Interbirth intervals are c¢.34-5 months. There is evidence that females are able to adjust the sex ratio before birth. Females have a dominance hierarchy that may inhibit the ability of other females to raise male offspring. High-ranking females tend to give birth to male infants more than do the lower ranking females, who produce more female offspring. Infanticide involving a subadult male killing a 4-week old infant was recorded in the population in Manu. Infanticide may be an adaptive behavior of males to reduce the interbirth interval from 2-3-5 years to less than a year.

Activity patterns. Activity budgets of Black Spider Monkeys at Lago Caiman varied throughout the year, determined by changes in dispersion of fruiting trees and fruit abundance. In the dry season (April-August), resting occupied 45-50% of the day, traveling 22-28%, and feeding 17-24%. In the wet season (September—March), Black Spider Monkeys rested less (37-42%), traveled more (30-40%), and spent about the same amount of time feeding, varying between months from ¢.12% to 23%. Social and other activities were relatively constant at ¢.5%. In the dry season, they have smaller daily homes ranges, feeding more on leaves and fewer,less widely dispersed fruit sources. At Lago Caiman, Black Spider Monkeys typically move and feed in the upper forest canopy (91% of all sightings), but they were often seen in the middle canopy and emergent trees. A similar activity budget was recorded for two groups of Black Spider Monkeys in Manu: resting 45%, traveling 26%, and feeding 29%. At the Rio Jiparana in the state of Rondonia, Brazil, they spent ¢.75% of their time in the lower and middle canopy 10-20 m above the ground. About 14% of the observations were in the top of the canopy at 2-25 m above the ground.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Black Spider Monkeys have a fission-fusion social organization, with large groups (sometimes called communities) usually traveling and foraging in subgroups of females and their young, occasionally with a male or multiple males. All male groups are also observed. Group sizes are 37-55 individuals. A group of 55 individuals at Lago Caiman had 15 adult males and 15 adult females—an unusual sex ratio because most groups of Black Spider Monkey are skewed toward females. At Manu, two groups each had five males and 15 and 16 females. An average subgroup size of 3-3 individuals was recorded from a number of localities in Rondonia, and subgroup sizes at Manu average 3-1 individuals (range 2-9), along with solitary individuals. Lago Caiman has a variable subgroup size of c.6 individuals. Females disperse, males are philopatric. Males associate more with other males in the group than with females, but males show more alloparental care than females. Males are territorial, and intergroup interactions occur at home range boundaries, marked by aggressive calling and “ook-barking” when two groups confront each other with 50-150 m between them. Sometimes males, with fur raised (piloerection), charge and chase each other. After one group retreats, ook-barking can continue for an hour or so. Home range sizes are 153-231 ha in Manu, 295 ha at Lago Caiman, and 340 ha at La Chonta Forest Reserve. Mean daily movements are 1977 m (465-4070 m) at Manu and 2338 m (460-5690 m) at Lago Caiman. Males travel farther during the day than females. Over eleven months, males in a group at Lago Caiman traveled an average of 2546 m/day and females 1972 m/day. They also traveled faster: males averaged 957 m/hour and females 778 m/hour. This difference was believed to result from home range border patrolling by males. Males tended to travel in larger subgroups (average 8-5 individuals) when near home range borders than when in more central parts of their home range (7-4 individuals). Adult females occupied, and preferentially used, a core area of the group’s home range. In Bolivia, densities of Black Spider Monkeys are usually 5-25 ind/km?. Densities in the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park (Lago Caiman) are as high as 32 ind/km?®. Density of 31 ind/km? was recorded in terra firma lowland forest in Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Peru. High densities are correlated positively with habitat heterogeneity. Densities in Brazil vary according to forest type: 3-1-9-6 ind/km? in terra firma forests and 2-6-3-6 ind/km? in varzea (white-water flooded forest). Surveys along the Rio Jurua found densities in non-hunted areas as high as 25 ind/km?, but at four hunted locations, Black Spider Monkeys were too rare to be counted at two and densities at the other two were only 0-6-1-3 ind/km?. Average density was 4-2 ind/km?* at eight non-hunted sites in the Amazon Basin and 0-7 ind/km? at ten moderately to heavily hunted sites.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Endangered on The [UCN Red List. The Black Spider Monkey is widespread and common where not hunted for its meat, but it has been extirpated or is threatened by hunting and habitat loss in many areas. It exhibits little or no adaptability to human pressures. Forests in the southern part of its distribution in the states of Rondonia, Mato Grosso, and Acre, in particular, are being devastated along the agricultural frontier moving northward through the Brazilian Amazon. Cattle ranching and forest loss are also widespread in northern Bolivia and south-eastern Peru. Additional threats include hunting and deforestation associated with highway development projects, agricultural expansion for soy production, mining activities in the Peruvian Amazon, and habitat degradation from selective logging, which may affect key fruiting species and forest structure and open up new areas for hunting. The Black Spider Monkey is known to occur in ten protected areas in Bolivia (Ambor6 National Park, Beni Biological Station and Biosphere Reserve, Carrasco National Park, Isiboro Sécure National Park, Madidi National Park, Manuripi-Heath National Reserve, Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Pilon Lajas Biosphere Reserve and Communal Lands, and Rios Blanco y Negro National Reserve); 14 in Brazil (Abufari Biological Reserve, Amazonia National Park, Cunia Ecological Station, Guaporé Biological Reserve, Iqué Ecological Station, Jara Biological Reserve, Jutai-Solimoes Ecological Reserve, Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve, Mapinguari National Park, Pacaas Novos National Park, Rio Acre Ecological Station, Samuel Ecological Station, Serra da Cutia National Park, and Serra do Divisor National Park); and three in Peru (Bahuaja-Sonene National Park, Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve, Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve). It may also be found in the Tambopata National Reserve in Peru.

Bibliography. Aquino & Encarnacion (1994b), Di Fiore, Link & Campbell (2011), Di Fiore, Link & Dew (2008), Felton, Felton, Wood, Foley et al. (2009), Felton, Felton, Wood & Lindenmayer (2008), Gibson et al. (2008), Heltne & Kunkel (1975), Iwanaga & Ferrari (2001, 2002a), Kellogg & Goldman (1944), Peres (1990, 1997a, 2000c), Sampaio et al. (1993), Soini et al. (1989), Symington (1988a, 1988b), Terborgh (1983), Wallace, R.B. (2005, 2006, 2008a, 2008b), Wallace, Mittermeier et al. (2008), Wallace, Painter, Rumiz & Taber (2000), Wallace, Painter & Taber (1998), White (1986).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.