Pseudopaludicola atragula, Pansonato, André, Mudrek, Jessica Rhaiza, Veiga-Menoncello, Ana Cristina Prado, Rossa-Feres, Denise De Cerqueira, Martins, Itamar Alves & Strüssmann, Christine, 2014

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3861.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:FFCFBCF2-F2BF-44ED-ACD7-652643DBE362 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5658229 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E9788256-FFC3-FFB2-FF77-FD1AFC13FC66 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Pseudopaludicola atragula |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Pseudopaludicola atragula sp. nov.

( Figures 1–3 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 )

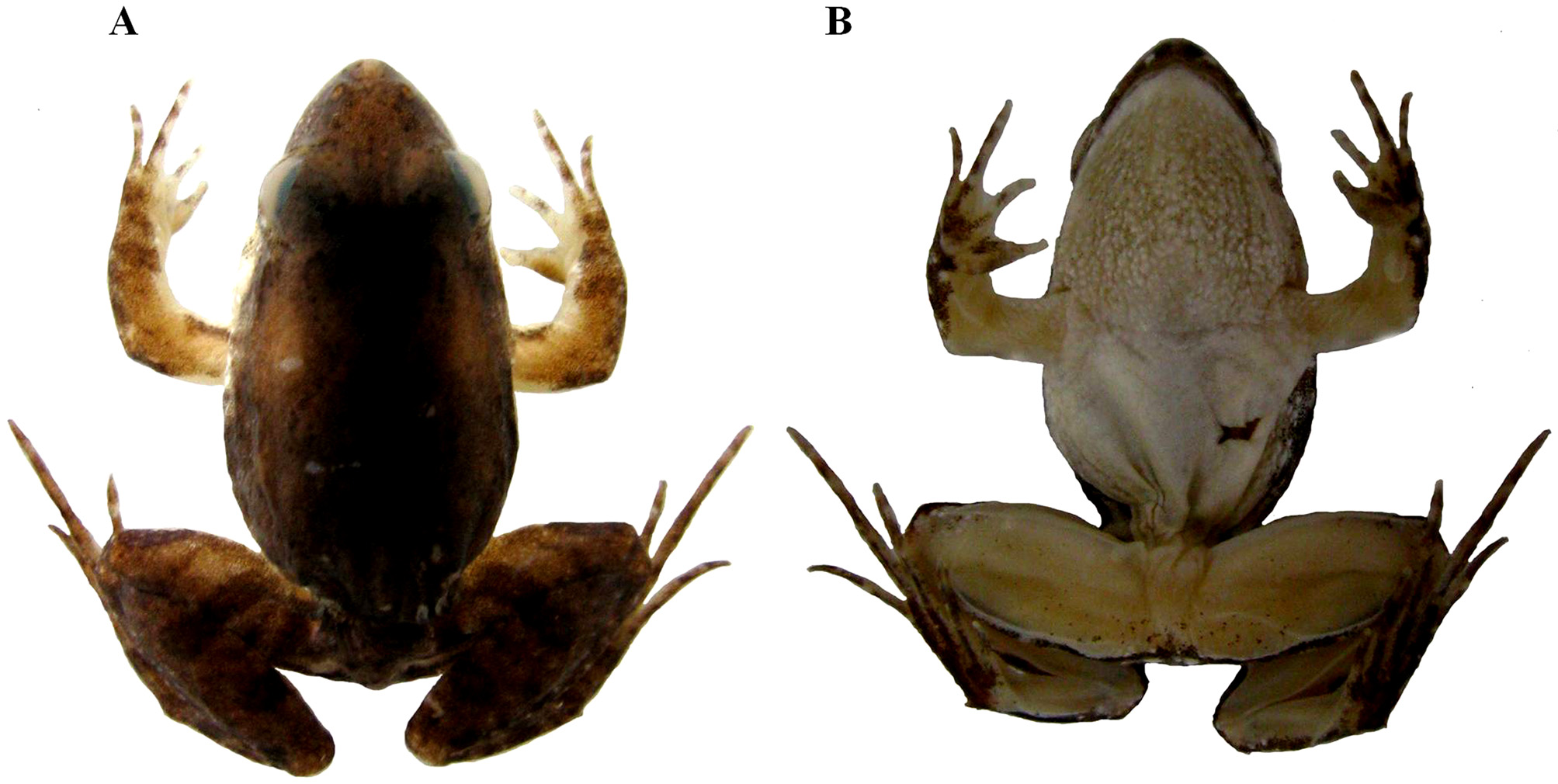

Holotype. Adult male ( UFMT 16576; Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 ) collected on 10 January 2013 by A. Pansonato and J. R. Mudrek, on a permanent swamp ( 20º20’31”S; 49º11’42”W) in the smallholding named “sítio Boa Esperança”, municipality of Icém, northwest region of the state of São Paulo, Brazil.

Paratypes. Three adult males (DZJSRP 8727–8; 8747) collected on 23 February 2005 by C. P. Candeira, R. A. Silva and F. R. Silva; two adult males ( UFMT 16198–9) and one adult female ( UFMT 16550) collected on 0 2 March 2012 by A. Pansonato and R. A. Silva; nine adult males ( UFMT 16200–1; 16551–5; 16557; 16571), three adult females ( UFMT 16202; 16572; 16582), and one juvenile ( UFMT 16556) collected on 10 January 2013 by A. Pansonato and J. R. Mudrek, from the same locality of the holotype. Nine adult males ( UFMT 16203–6; 16576–80), three adult females ( UFMT 16573–5), and one juvenile ( UFMT 16581) collected on 10 January 2013 by A. Pansonato and J. R. Mudrek at district of Nova Itapirema ( 21º04’54”S; 49º31’11”W), municipality of Nova Aliança, São Paulo, Brazil.

Referred specimens. We here provide a list of all name usages that we have found in the literature, i.e., names once applied to material that we recognize as strictly corresponding to the species being described here: Pseudopaludicola aff. canga (from Icém, SP)—Duarte et al. (2010: 4) and Andrade & Carvalho (2013: 396); Pseudopaludicola aff. falcipes – Silva et al. (2008: 126–130) and Silva et al. (2011: 613–614); Pseudopaludicola falcipes — Silva et al. (2012: 1416–1422); Pseudopaludicola sp. 2 ( aff. canga )— Veiga-Menoncello et al. (2014: 263–270).

Diagnosis. The new species is assigned to the genus Pseudopaludicola based on the presence of hypertrophied antebrachial tubercles ( Lynch 1989). Pseudopaludicola atragula sp. nov. is diagnosed by the following combination of characters: (1) small size (SVL 12.2–15 mm in males and 15.5–16.7 mm in females); (2) absence of either T-shaped terminal phalanges or expanded toe tips (disks or pads); (3) short hindlimbs, with tibiotarsal articulation only reaching the eye; (4) areolate vocal sac, with dark reticulation; (5) karyotype with 2n=18 chromosomes; (6) advertisement call composed of a single note with 9–36 nonconcatenated pulses (resembling the sound of clockwork motors used in wind-up toys); (7) note duration of 0.3– 0.7 s; (8) note repetition rate of 42–98 notes/min; (9) absence of harmonics; (10) dominant frequency of advertisement call 3617.6–4263.6 Hz.

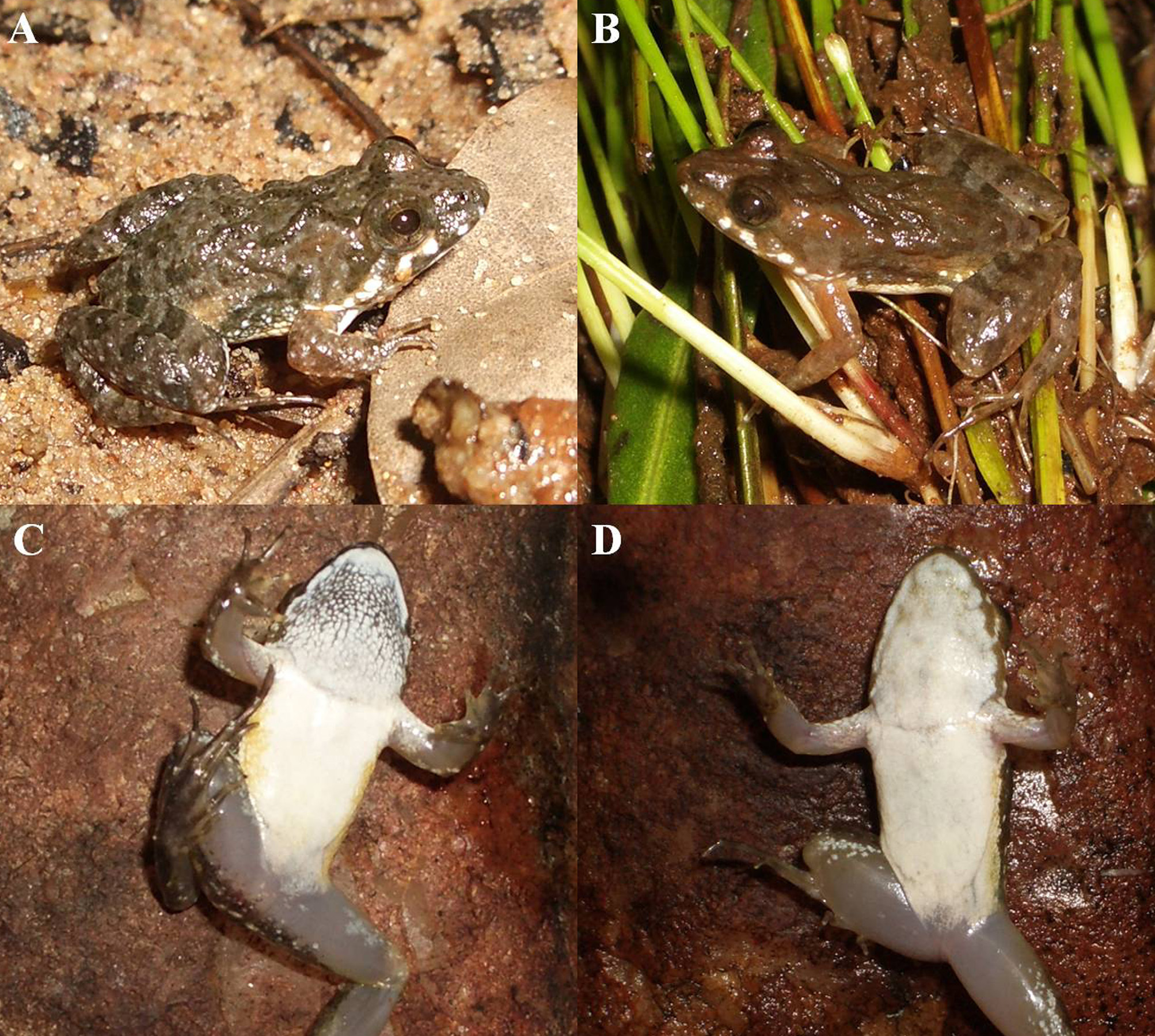

Description of holotype. Small size (SVL 14.07 mm). Canthus rostralis indistinct, rounded, smooth; vocal sac single (subgular), with areolate, whitish dark reticulations ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 A); vocal slits present; choanae well-separated from each other. Surfaces of dorsum, venter, upper eyelids, belly and throat smooth; H-shaped glandular ridge on shoulder region. Snout rounded to subovoid in dorsal view, and acuminate in profile; head wider than long; sides of head (upper lips, under the eyes, and tympanum area) and flanks with white granules ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 B). Nostrils slightly protuberant, directed anterolaterally, closer to tip of snout than to eyes; pupil rounded; upper eyelids; tympanum indistinct; vomerine teeth absent; tongue ovoid, posteriorly free. Cloaca smooth. Inner metatarsal tubercle oval; outer metatarsal tubercle conical; toe tips slightly pointed, not webbed and extensively fringed to almost their tips ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 C); relative length of toes I<II<III~V<IV; subarticular tubercles large, rounded; supernumerary tubercles absent. Hand with fingers free ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 D), with tips rounded, not expanded; relative length of fingers I<II~IV<III; thumb thickened, with keratinized gray nuptial pad on internal surface; two subconical antebrachial tubercles, the distal one scarcely perceptible; outer metacarpal tubercle round; inner metacarpal tubercle elongated; subarticular finger tubercles rounded; supernumerary finger tubercles indistinct.

Color. In life ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 A–B), dorsum dark gray; flanks pale gray; no vertebral line from the snout to vent; belly white; upper lips with white spots which extend to the insertion of the forelimbs; vocal sac with large white areolations (nearly circular protuberances), interspersed among dark reticulation. Dark reticulation is particularly evident in the anterior half of the vocal sac. In preservative, dorsum grayish brown, with darker brown blotches; belly whitish; ventral surface of hands and feet dark gray, mottled; white spots on upper lips, extending to the dorsal insertion of the forelimbs and to the flanks; vocal sac with large white areolations over a grey, nearly translucent skin, peppered with black melanophores. Dark transverse stripes in thigh and shank, tarsus and foot, and forearm.

Variation. Dorsal coloration is highly variable, with nearly 25% of the examined specimens presenting a light, thin vertebral stripe, from the tip of the snout to vent. In preserved specimens, the gular region may vary from light to darker grey, always peppered with black melanophores. Females have a more robust body and their gular region, although areolate, is always unpigmented, clear white ( Table 1 View TABLE 1 ).

Holotype Males Females

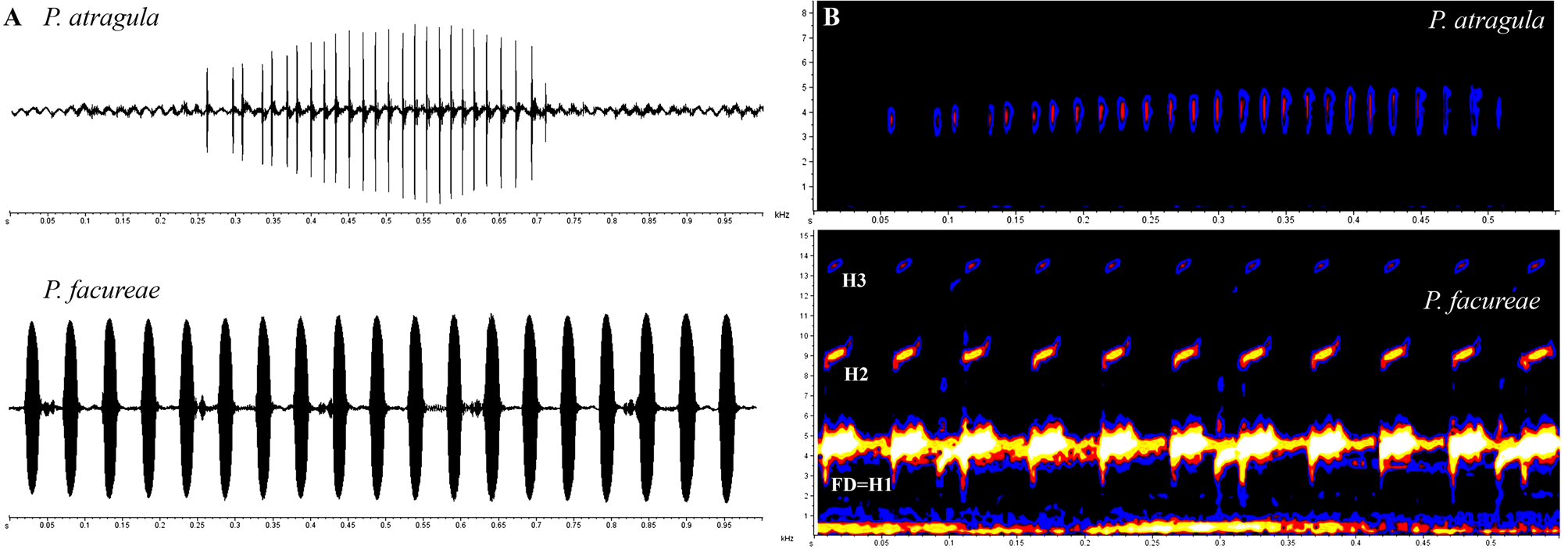

(N=22) (N=7) Description of the advertisement call. We analyzed 41 calls of four specimens of Pseudopaludicola atragula ( Table 2). A typical advertisement call of the new species ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ) consists of a single pulsed note, with 9–36 (mean 22.8±5.4) pulses emitted in a very short period of time, during a single airflow ( McLister et al. 1995). The call (= one note) resembles the sound of clockwork motors used in wind-up toys. Mean duration of each note is 0.45± 0.07 s (0.3– 0.7 s). Inter-notes interval ranges from 0.5± 0.2 s (0.04– 0.9 s) and average rate of notes per minute is 65.3±15.1 notes/min (42–98). Mean frequency ranged from 2500.01 (±341.1) Hz to 5088.5 (±249.2) Hz, and mean dominant frequency from 3981.5±156.9 Hz (3617.6–4263.6 Hz). Mean duration of each pulse is 0.003± 0.001 s (0.001– 0.007 s). Inter-pulses interval ranges from 0.01± 0.008 s (0.002– 0.064 s). Average rate of pulses per minute is 2935.5±549.8 pulses/min (1436–3957).

Comparison with other species. A combination of external and/or internal morphological characters, bioacoustic properties of the call, and/or karyotype allows to distinguish the new species from all other 17 Pseudopaludicola species (from now on, characters of compared species in parentheses). From eight out of the 13 Pseudopaludicola species not belonging to P. pusilla group ( P. ameghini , P. c a ng a, P. f a cu re a e, P. falcipes , P. giarettai , P. hyleaustralis , P. mineira , P. m y s t ac a l i s, P. murundu , P. parnaiba , P. pocoto , P. saltica , and P. ternetzi ) the new species differs: from P. falcipes , by the presence of an abdominal fold (abdominal fold interrupted or absent; Lobo 1996; Lavilla & Cei 2001); from P. murundu , and P. saltica , by the shorter hindlimbs, with tibio-tarsal articulation reaching the nostrils (presence of very long hindlimbs, with tibio-tarsal articulation reaching beyond the end of the snout; Toledo et al. 2010; Pansonato et al. 2013); from P. giarettai , by the smaller body size (16.2–18.0 mm SVL in males) and by the relative length of fingers (finger I shorter than finger IV; Carvalho 2012); from P. ameghini , by the smaller body size ( 14.1–19.3 mm SVL in males and 17.3–22.7 mm SVL in females; Haddad & Cardoso 1987; Pansonato et al. 2013); from P. mineira , by head longer than wide (head as long as wide; Pereira & Nascimento 2004); from P. ternetzi , by the smaller body size (SVL of males 16.0– 18.6 mm; SVL of females 16.0– 22.2 mm; Lobo 1996).

Advertisement call parameters Pseudopaludicola atragula sp. nov.

N=41 (4)

Number of pulses per note 22.8±5.4 (9–36)

Note duration (s) 0.45±0.07 (0.3–0.7)

Inter-notes interval (s) 0.5±0.2 (0.04–0.9)

Pulse duration (s) 0.003±0.001 (0.001–0.007) Inter-pulses interval (s) 0.01±0.008 (0.002–0.064) Minimum frequency (Hz) 2500.01±341.1 (1932.7–3331.3) Maximum frequency (Hz) 5088.5±249.2 (4322.8–5578.4) Dominant frequency (Hz) 3981.5±156.9 (3617.6–4263.6) Average rate of notes/min 65.3±15.1 (42–98)

Average rate of pulses/min 2935.5±549.8 (1436–3957) The appearance of the vocal sac of male Pseudopaludicola atragula —areolate, whitish, with dark reticulation—distinguishes the new species from P. ameghini , P. falcipes , P. g i are t t ai, P. hyleaustralis , and P.

pocoto , which present vocal sac yellowish or light cream ( Haddad & Cardoso 1987; Carvalho 2012; Pansonato et al. 2012a; Pansonato et al. 2013; Magalhães et al. 2014), from P. boliviana , P. mineira , P. mystacalis , P. saltica , and from topotypic specimens of P. ternetzi , which present vocal sac not areolate and uniformly whitish (Miranda- Ribeiro 1837; Lobo 1994; De la Riva et al 2000; Pansonato et al. 2013), from P. murundu , by the vocal sac not areolate and uniformly dark ( Toledo et al. 2010).

Presently, only four species cannot be distinguished from Pseudopaludicola atragula based solely on external morphology: P. canga , P. f acureae, P. parnaiba , and P. pusilla . Internally, however, P. atragula is distinguished from congeners belonging to the P. pusilla group ( P. boliviana , P. ceratophyes , P . llanera and P. pusilla ) by the absence of either T-shaped terminal phalanges or expanded toe tips ( Lynch 1989). Advertisement call structure distinguishes Pseudopaludicola atragula from all 14 congeners ( Figure 5–6 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 ) for which call descriptions are available ( P. ameghini , P. boliviana , P. canga , P. f a c ure a e, P. falcipes , P. giarettai , P. hyleaustralis , P. m i n e i r a, P. mystacalis , P. murundu , P. parnaiba , P. pocoto , P. saltica and P. ternetzi ). Call consisting of a single pulsed note and lower dominant frequency (3617.6–4263.6 Hz) differ Pseudopaludicola atragula from two congeners having notes with concatenated pulses ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 A): P. mystacalis ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 A; call consisting of sequences of notes, each note composed of 12–20 pulses, with dominant frequency 4478.9–5340.2 Hz; Pansonato et al. 2013; 2014), and P. boliviana ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 B; call consisting of sequences of notes, each note composed of 3–6 pulses, with dominant frequency 4942–5224 Hz; Duré et al. 2004).

Among species for which calls composed of pulsed notes with nonconcatenated pulses were reported ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 B; see also Table 3 in Magalhães et al. 2014), Pseudopaludicola atragula ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 C) differs from P. ameghini , P.

falcipes , P. mineira , P. murundu , P. saltica and P. ternetzi by a higher number of pulses per note (9–36 pulses), higher note duration (0.3– 0.7 s), and/or lower dominant frequency (3617.6–4263.6 Hz). In P. ameghini ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 D) there are 3–6 pulses per note, and note duration is 0.04– 0.11 s ( Pansonato et al. 2013); in P. ternetzi ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 E) there are 3–6 pulses per note, and note duration is 0.01– 0.09 s in populations from Minas Gerais and São Paulo ( Cardozo & Toledo 2013); in P. murundu ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 F), there are 2–6 pulses per note, note duration is 0.03– 0.14 s, and dominant frequency is 4875–6370 Hz ( Toledo et al. 2010; Pansonato et al. 2014); in P. saltica ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 G), there are 1–4 pulses per note, and note duration is 0.03– 0.1 s ( Pansonato et al. 2013); in P. falcipes ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 H), there are 2 pulses per note and dominant frequency is 4200–5800 Hz ( Haddad & Cardoso 1987); in P. mineira ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 I), there are 2 pulses per note, note duration is 0.04 s, and dominant frequency is 4306–4823 Hz ( Pereira & Nascimento 2004); in P. po c o t o ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 J), there are 2–3 pulses per note, note duration is 0.13– 0.29 s, and dominant frequency is 5168–6374 Hz ( Magalhães et al. 2014).

The new species differs from P. canga , P. f a c u re a e, P. giarettai , P. hyleaustralis , and P. parnaiba ( Figure 5 View FIGURE 5 C) by having pulsed (9–36 pulses) notes, with higher note duration (0.3– 0.7 s) and lower note repetition rate (42–98 notes/min). All five above-mentioned species present non-pulsed notes ( Giaretta & Kokubum 2003; Carvalho 2012; Pansonato et al. 2012; Andrade & Carvalho 2013; Pansonato et al. 2013; Roberto et al. 2013). Advertisement calls correspond to long series of non-pulsed notes emitted at a relatively fast rate in P. parnaiba ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 L; 6–46 non-pulsed notes, note duration 0.01– 0.04 s and note repetition rate 16–162 notes/min; Roberto et al. 2013), in P. hyleaustralis ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 M; 11–74 non-pulsed notes, note duration 0.02– 0.05 s and note repetition rate 503.8–623.2 notes/min; Pansonato et al. 2012), and in P. f a c u re a e ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 N; 3–53 non-pulsed notes, note duration 0.02– 0.035 s and note repetition rate 480–1860 notes/min; Andrade & Carvalho 2013). In P. c a ng a, the advertisement call consists of short series of up to 19 non-pulsed notes ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 O; note duration 0.01– 0.03 s and note repetition rate 689–944 notes/min; Giaretta & Kokubum 2003; Pansonato et al. 2012). In P. giarettai ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 P; Carvalho 2012) the advertisement call consists of a non-pulsed note resembling a whistle.

Species; Genbank access 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 number

1. P. atragula ;

KJ146996 View Materials –KJ14998

2. P. falcipes ; KJ146972 View Materials 0.166

3. P. ameghini ; KJ146975 View Materials 0.101 0.122

4. P. f a c u re a e; KJ146978 View Materials 0.032 0.161 0.103

5. P. mystacalis ; 0.094 0.148 0.098 0.094 KJ146983 View Materials

6. P. c a n g a; KJ146988 View Materials 0.079 0.137 0.088 0.083 0.085 7. Pseudopaludicola 0.173 0.126 0.115 0.163 0.133 0.147 sp.— P. pusilla group;

KJ146992 View Materials

8. P. saltica ; KJ147002 View Materials 0.147 0.090 0.123 0.149 0.144 0.146 0.124 9. P. m i n e i r a; KJ147025 View Materials 0.170 0.075 0.122 0.174 0.146 0.154 0.122 0.048 10. P. murundu ; 0.149 0.073 0.114 0.151 0.139 0.133 0.110 0.025 0.043 KJ147031 View Materials

11. P. boliviana —P. 0.179 0.121 0.134 0.174 0.152 0.162 0.071 0.121 0.115 0.110 pusilla group; KJ147049 View Materials

12. P. ternetzi ; KJ147054 View Materials 0.106 0.126 0.016 0.108 0.099 0.083 0.119 0.125 0.128 0.119 0.134 13. Pseudopaludicola sp. 0.072 0.135 0.080 0.076 0.080 0.018 0.145 0.140 0.152 0.128 0.158 0.078 3 ( aff. canga ); KJ147013 View Materials

A lower dominant frequency also differ the advertisement call of Pseudopaludicola atragula from the calls of P. facureae (4076–5108 Hz; Andrade & Carvalho 2013) and P. parnaiba (4220.5–5168 Hz; Roberto et al. 2013). Absence of harmonics differ the call of the new species from that of P. giarettai (with four harmonics; Carvalho 2012) and from P. facureae (with three harmonics; present study).

Finally, the number of chromosomes (2n=18) distinguishes Pseudopaludicola atragula (Duarte et al. 2010; treated therein as “ Pseudopaludicola aff. canga ”) from P. falcipes , P. mineira , P. murundu , and P. saltica (2n=22), P. ameghini and P. ternetzi (2n=20), and P. mystacalis (2n=16) (Duarte et al. 2010; Fávero et al. 2011).

Geographic distribution. Pseudopaludicola atragula is a Brazilian endemic species, presently known from two localities in the northwest region of the state of São Paulo, in southeastern Brazil: the type locality (municipality of Icém, 20º21’33”S; 49º11’55”W), and the district of Nova Itapirema, municipality of Nova Aliança ( 21º04’54”S; 49º31’11”W), approximately 100 km in a straight line southwards from Icém.

Genetic distance. The intraspecific genetic distances (uncorrected p-distances) between Pseudopaludicola atragula and species in the P. pusil la group were greater (> 17%) than distances between P. atragula and closely related species that lack T-shaped terminal phalanges and share the same diploid number 2n=18 chromosomes (3.2 to 7.9%; Table 3).

Habitat and Conservation. In the northwestern region of the state of São Paulo, Pseudopaludicola atragula is always found in sympatry with P. mystacalis , which also occurs together with P. ternetzi in some localities (R.M. Pelinson pers. comm.). These three Pseudopaludicola species occur syntopically at the type-locality of P. atragula which, although being the least frequent of the three, can be locally abundant, their representatives being found along the whole rainy season, from September to March ( Santos et al. 2007; Silva et al. 2008; 2011).

Pseudopaludicola atragula occurs in groundwater upwelling sites where the water runs slowly, forming temporary and permanent ponds and swamps with a large amount of marginal herbaceous vegetation (see Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 f in Silva et al. 2008, who treated the species as Pseudopaludicola aff. falcipes and listed other anuran species found syntopically; see also Silva et al. 2012). Males call from both wet sites and sites with shallow water, generally from the base of small individual grasses, in areas sparsely covered by vegetation and interspersed with areas without vegetation ( Santos et al. 2007; Silva et al. 2011).

In the municipalities of northwestern region of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, populations of Pseudopaludicola and of other anuran species are under strong pressure due to habitat destruction. The region is considered the most deforested and fragmented in that state, with less than 9% of the original vegetation of seasonal Semideciduous Forests and Cerrado savannahs. Main causes of habitat loss are due to agribusiness (mainly sugarcane crops) and urbanization. Unsustainable farming practices are leading to high levels of soil erosion, sedimentation of streams, and degradation of aquatic ecosystems. Additionally, conservation units are scarce in the northwestern region of São Paulo ( Martinelli & Filoso 2008; Necchi Jr. 2011).

Etymology. The specific epithet is derived from the Latin words “ atra ”, meaning dark, black, and “ gula ”, meaning throat or gullet. It is used in reference to the dark gular region of most males (in life) – unusual within the genus Pseudopaludicola – with white areolations interspersed among dark reticulation.

Concluding remarks. Morphologically and cytogenetically, Pseudopaludicola atragula most closely resembles P. facureae . Indeed, based on similarities in the chromosome numbers of the two species (2n=18), Duarte et al. (2010) suggested that the populations from Icém (São Paulo, Brazil) and Uberlândia (Minas Gerais, Brazil), both treated by those authors as “ Pseudopaludicola aff. canga ”, could belong to the same taxon.

Visual examination of qualitative morphological characters of males and females in our sample of Pseudopaludicola atragula did not evidenced any diagnostic character to distinguish this taxon from P. f ac u re ae. Comparative analyses of morphometric data through a PCA, however, clearly allowed distinguishing the two taxa ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 ). The first two axes of the PCA explained 87% of the total variability in males ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 A) and higher loadings corresponded to snout-vent length, head length, and thigh length. The PCA explained 85% of the total variability in females ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 B) and higher loadings corresponded to snout-vent length, head length, and foot length. The DFA with morphometric measurements, using all specimens, assigned 100% of the individuals of Pseudopaludicola atragula and 100% of the individuals of P. f acureae to the correct species ( Table 4).

Males Females

True group True group

Assigned to P. atragula P. facureae P. atragula P. facureae P. atragula 22 0 7 0 P. facureae 0 13 0 9 Number correct 22 13 7 9

% 100 100 100 100 Bioacoustic parameters and spectrograms presented herein also evidenced the taxonomic validity of the species from northwestern state of São Paulo. As here shown, with a single contraction of the trunk muscles, males of P. atragula emit an advertisement call composed of a single pulsed note with 9–36 nonconcatenated pulses, without harmonics, resembling the sound of clockwork motors used in wind-up toys. Calls are also composed of single notes and present harmonics only in P. giarettai , but in this species notes are non-pulsed, there are four harmonics, and the call resembles a whistle. In the remaining species of Pseudopaludicola where bioacoustic parameters were already analyzed, the call consists in a succession of series of notes. In particular, we call attention to the fact that calls already described within the genus Pseudopaludicola might be divided in three distinct groups according to type of notes: non-pulsed notes; notes with concatenated pulses, and notes with nonconcatenated pulses ( Figure 5–6 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 ). Bioacoustic data, therefore, are here confirmed to represent a reliable tool in the recognition of cryptic species within the genus Pseudopaludicola .

Acoustic parameters of calls and the spectrogram of topotypes of Pseudopaludicola atragula are readily distinguished from topotypical advertisement calls of P. facureae , composed of series of 2–55 (mean 15.8±10.1) non-pulsed notes, with series duration of 0.1– 4.3 s, emitted at intervals of 0.2– 1.7 s ( Table 5; Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ). Mean note duration in this species is 0.02±0.005 (0.01–0.04), emitted on average at intervals of 0.03±0.03 (0.01–0.4) with average rate of notes per minute of 1249.1±388.5 (646–2000). Mean frequency ranges from 2688.5 (±573.9) Hz to 5947.9 (±336.8) Hz, and mean dominant frequency is 4559.4±212.2 (4306.6–4995.7), usually concentrated in the first harmonic ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 B). Therefore, the call of P. atragula differs from P. f ac u re ae by having pulsed notes, higher note duration, lower note repetition rate and dominant frequency, and especially in the absence of harmonics ( Figure 8 View FIGURE 8 ).

Evaluation of uncorrected pairwise distances revealed high genetic divergences between Pseudopaludicola atragula and its congeners (9.4–17.9%), except for species that share with P. atragula the diploid number of 2n=18 chromosomes. These findings seem to be in agreement to its phylogenetic relationships: P. atragula + P. f ac u re ae (genetic divergence of 3.2%) and P. canga + Pseudopaludicola sp. ( aff. canga ), showing genetic divergences of 7.2 and 7.9%, respectively, to P. atragula , were recovered as sister groups ( Veiga-Menoncello et al. 2014). Although our results revealed an overall high genetic distance among species of Pseudopaludicola , a lower genetic divergence was revealed when closely related species are compared (e.g., 1.6% between P. ameghini and P. ternetzi , and 2.5% between P. saltica and P. murundu ). This scenario is similar to that reported for certain species in the dendrobatid genus Ameerega ( Lötters et al. 2009) and in the hylid genus Osteocephalus ( Jungfer et al. 2013) . The uncorrected p-distance of 3.2% found between P. atragula and P. f a c ure a e is very similar to values regarded by some authors as a “strong molecular” and “substantial genetic” differentiation between related taxa, even though they could represent conspecific lineages, or cryptic species instead (e.g., Vences et al. 2011). By integrating morphological, bioacoustic and molecular data, evidence presented herein support the recognition of P. atragula as a new, valid species of the genus Pseudopaludicola .

As here reported, Pseudopaludicola atragula occurs syntopically with other two congeners at the type-locality: P. mystacalis and P. ternetzi . Although not yet studied in detail, co-occurrence is a rather frequent situation throughout the range of the genus ( e.g., Silva et al. 2008; Pansonato et al. 2012b; Pansonato et al. 2013). In general, individuals of Pseudopaludicola spp. seem to occupy habitats with vegetation consisting only in sparse, tall grasses, in seasonally flooded shallow areas or in permanent wet areas with a thin water film flow ( Santos et al. 2007; Silva et al. 2008; Giaretta & Facure 2009).

Geographical, morphological, ecological, bioacoustic, and genetic patterns of co-occurring species of Pseudopaludicola should be evaluated using integrative approaches, for a better understanding of habitat use, geographic distribution, and evolution in the genus.

Advertisement call parameters Pseudopaludicola facureae

N=280 (8)

Number of notes per series (s) 15.8±10.1 (2–55)

Series duration (s) 0.8±0.6 (0.1–4.3)

Inter-series interval (s) 0.5±0.2 (0.2–1.7)

Note duration (s) 0.02±0.005 (0.01–0.04) Inter-notes interval (s) 0.03±0.03 (0.01–0.4) Minimum frequency (Hz) 2688.5±573.9 (1114.3–3992.6) Maximum frequency (Hz) 5947.9±336.8 (5372.1–6771.4) Average rate of notes/min 1249.1±388.5 (646–2000)

TABLE 1. Measurements (mm) of the type series adult specimens of Pseudopaludicola atragula sp. nov.. Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation (minimum – maximum). N = number of specimens analyzed. “ Males ” include the holotype.

| SVL | 14.07 | 13.6±0.9 (12.2–15.1) | 15.9±0.5 (15.5–16.7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HL | 5.47 | 5.3±0.3 (4.7–5.9) | 6.1±0.3 (5.7–6.5) |

| HW | 4.69 | 4.6±0.2 (4.1–5.1) | 5.2±0.5 (4.6–5.7) |

| IOD | 1.18 | 1.1±0.08 (1–1.3) | 1.2±0.1 (1–1.4) |

| ED | 1.35 | 1.4±0.1 (1.2–1.7) | 1.6±0.1 (1.5–1.9) |

| END | 1.2 | 1.3±0.1 (1–1.6) | 1.5±0.2 (1.3–1.8) |

| IND | 1.1 | 1.1±0.1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.3±0.1 (1.1–1.4) |

| HAL | 3.93 | 3.9±0.3 (3.3–4.4) | 4.5±0.3 (4–4.8) |

| THL | 6.43 | 6.2±0.3 (5.7–6.8) | 7.2±0.4 (6.7–7.9) |

| TL | 7.09 | 6.7±0.5 (5.9–7.7) | 7.9±0.3 (7.4–8.3) |

| TAL | 4.02 | 3.8±0.3 (3.3–4.2) | 4.6±0.2 (4.1–4.9) |

| FL | 8.3 | 7.7±0.6 (6.5–8.7) | 9.2±0.5 (8.5–9.6) |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Leiuperinae |

|

Genus |