Palaeospondylus gunni TRAQUAIR , 1890

Gardner, James D., 2016, The Fossil Record Of Tadpoles, Fossil Imprint 72 (1 - 2), pp. 17-44 : 31-32

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.14446/FI.2016.17 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0634C846-C50E-E52F-4E9D-FA14FD68FD83 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Palaeospondylus gunni TRAQUAIR , 1890 |

| status |

|

Palaeospondylus gunni TRAQUAIR, 1890 from the Middle Devonian of Scotland and a “tadpole” from the Early Cretaceous of Israel

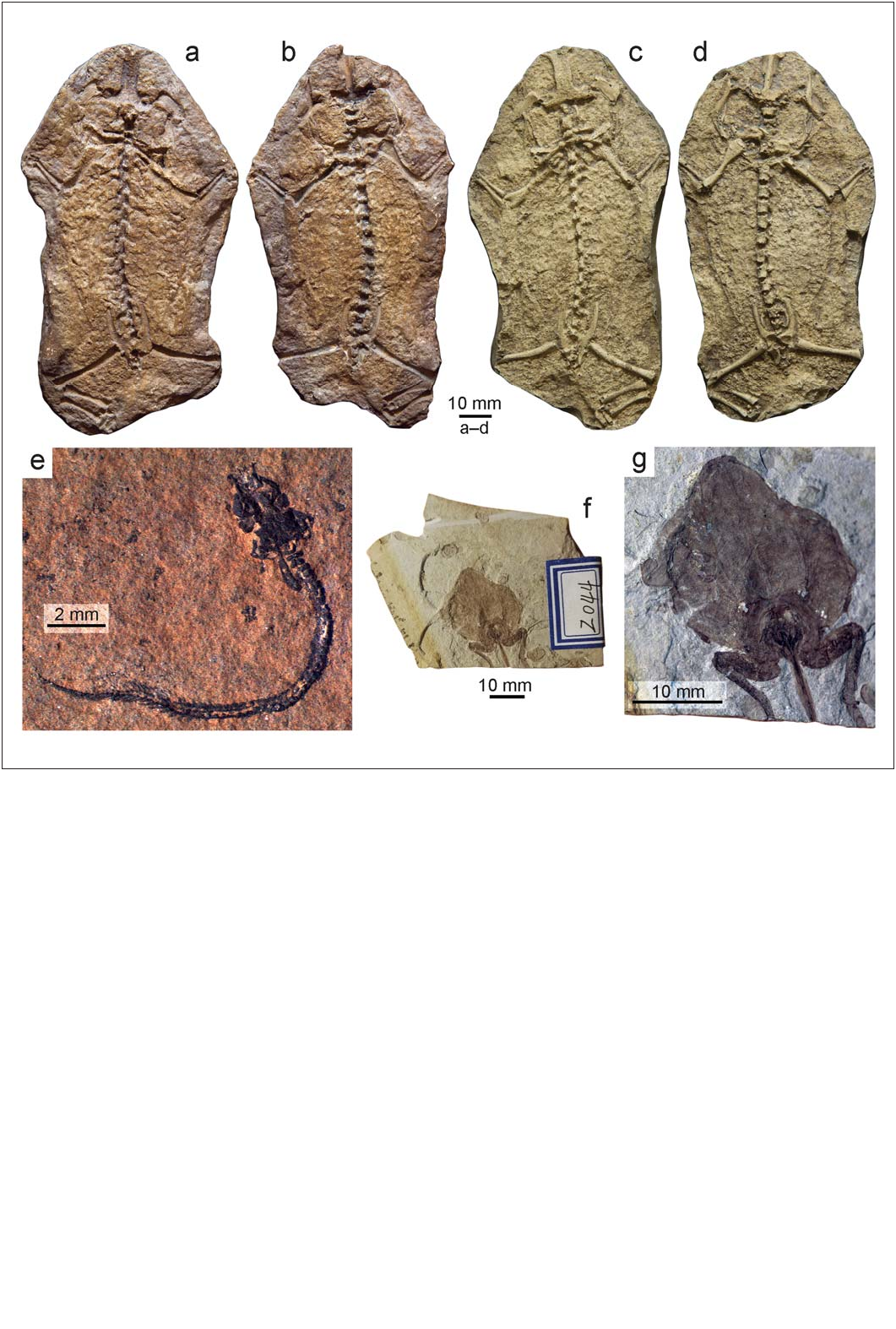

Two kinds of small-bodied, moderately elongate, aquatic, and larval-like fossils have been regarded as possible tadpoles. The first of these is Palaeospondylus gunni TRAQUAIR, 1890 , an enigmatic fish-like vertebrate known from hundreds of articulated skeletons, none longer than about 60 mm ( Text-fig. 2e View Text-fig ). Most examples of this fossil originate from the Achanarras Quarry in the Highlands of Scotland, a Middle Devonian locality that has yielded abundant specimens belonging to about 16 species of jawless and jawed fish (e.g., Trewin 1986, Johanson et al. 2011). Despite being known by hundreds of articulated skeletons, Palaeospondylus has proven challenging to study and interpret because all the specimens are small and most are flattened or crushed. Since its discovery, the identity of Palaeospondylus has been controversial: at various times it has been regarded either as a larva or an adult, and it has been referred to most major groups of fish (see historical summaries by Moy-Thomas 1940, Forey and Gardiner 1981, Thomson 1992, 2004, Johanson et al. 2010, Janvier and Sanson 2016).

Palaeospondylus twice has been interpreted as a tadpole-like organism. In their brief treatments of Palaeospondylus, Dawson (1893: 186) stated “I should not be surprised if it should come to be regarded either as a forerunner of the Batrachians or as a primitive tadpole”, while nearly a century later Jarvik (1980: 218) suggested “ Palaeospondylus may be related to the anurans”. Although Jarvik (1980: 218) went on to suggest that Palaeospondylus might also be a larval osteolepiform fish, most of his short discussion on the identity of Palaeospondylus focused on comparing it to extant and fossil tadpoles, and also to a problematic fossil discussed below from the Early Cretaceous of Israel. Jarvik (1980: 218) cited two morphological similarities between Palaeospondylus and bonafide tadpoles: 1) ring-shaped vertebrae and 2) the external shape of the tail. He bolstered that comparison by including side-by-side drawings of a Palaeospondylus skeleton and a Recent anuran tadpole depicted at the same size and in virtually identical poses ( Jarvik 1980: fig. 153). Forey and Gardiner (1981: 136) countered that neither of the features cited by Jarvik (1980) are unique to tadpoles and, thus, are hardly convincing for regarding Palaeospondylus as a tadpole. There also are significant osteological differences between Palaeospondylus and tadpoles. For example, the cranium and branchial skeleton in Palaeospondylus are unlike those of tadpoles (cf. Forey and Gardiner 1981: fig. 1 versus Duellman and Trueb 1986: figs 6-6D, E, 6-7B). Further, as was alluded to by Moy-Thomas (1940: 407), whereas the caudal fin in Palaeospondylus is supported internally by a series of well-developed, bifurcating radials (see Text-fig. 2e View Text-fig ), the caudal fin in tadpoles is a soft structure that lacks any internal supports (cf. Moy-Thomas 1940: text-fig. 6, pl. 25 versus Wassersug 1989: fig. 1). The only resemblances between Palaeospondylus and tadpoles are those common to aquatic, larval vertebrates in general: small size; elongate form; tail present and bearing dorsal and ventral fins; simple axial skeleton; and rudimentary girdles and appendages.

Although clearly not a tadpole, the affinities of Palaespondylus remain elusive. Work from the 1980s onwards has viewed Palaespondylus as a larval fish. Forey and Gardiner (1981) revived the idea that Palaespondylus was a larval lungfish, an idea that later received support from Thomson et al. (2003; see also Thomson 2004), who proposed that the co-occuring lungfish Dipterus valenciennesi SEDGWICK et MURCHISON, 1829 likely was the adult form. The larval lungfish hypothesis has been contradicted by the subsequent discovery of a small Dipterus fossil at the Achanarras Quarry that falls within the size range of Palaespondylus , but is morphologically distinct in possessing well-developed tooth plates ( Newman and Blaauwen 2008), and by developmental work that showed Palaespondylus possesses a suite of features not seen in larval lungfish and also lacks features expected for larval lungfish ( Joss and Johanson 2007). Recent histological studies revealed a novel skeletal tissue unique to Palaespondylus and suggest its affinities lie within the osteichthyians or bony fishes ( Johanson et al. 2010, 2011). Most recently, Janvier and Sanson (2016) revived the idea that Palaespondylus might be related to hagfishes by noting general resemblances between the two taxa, although they admitted there are no obvious synapomorphies to support that relationship.

A superficially Palaespondylus -like fossil from the Early Cretaceous (Aptian) of Israel also has been interpreted as a tadpole. The fossil was collected from the same locality (Amphibian Hill, at Makhtesh Ramon) that yielded over 200 metamorphosed anuran skeletons of the basal pipimorphs Thoraciliacus rostriceps and Cordicephalus gracilis (e.g., Nevo 1968, Trueb 1999, Roček 2000, Trueb and Báez 2006, Gardner and Rage 2016) and a dozen tadpole body fossils referable to Thoraciliacus ( Roček and Van Dijk 2006) . The fossil was described and figured twice as a tadpole by Eviatar Nevo: first briefly in his short paper announcing the discovery of frog fossils at Makhtesh Ramon ( Nevo 1956: 1192, fig. 2) and then in more detail in his unpublished PhD thesis ( Nevo 1964: 36–37, 106–108, pl. VII). Nevo (1964: 36) also mentioned that Makhtesh Ramon had yielded three additional tadpole fossils (all larger and presumably representing later ontogenetic stages), but he did not describe or discuss those further; presumably those three larger specimens were among the 12 bonafide tadpoles described by Roček and Van Dijk (2006) in their ontogenetic study of Cretaceous pipimorphs. Curiously, in his subsequent monographic treatment of anurans from Makhtesh Ramon, Nevo (1968: 258) only mentioned “one tadpole”. Based on Nevo’s (1956) paper, later workers generally accepted his tadpole identification (e.g., Hecht 1963: 22, Griffiths 1963: 282, Špinar 1972: 164, Jarvik 1980: 218, Metz 1983: 63) and, until the description of the older (Hauterivian or Barremian) size series of Shomronella tadpoles by Estes et al. (1978), the Makhtesh Ramon fossil was regarded as the geologically oldest tadpole fossil. Only Estes et al. (1978: 375) questioned whether the fossil was a tadpole, but they did not discuss it further. This Palaespondylus -like specimen was not among the 12 bonafide tadpole fossils from Makhtesh Ramon that were available for Roček and Van Dijk’s (2006) ontogenetic study (Z. Roček, pers. comm. 2016).

Based on Nevo’s (1964) more detailed description, the purported tadpole fossil from Makhtesh Ramon is about 33 mm long. According to Nevo (1964: 36) the specimen “is preserved as a brown limonitic cast and imprint. It consists of a well demarcated head and a long body and tail.” Nevo (1964) described the head as roughly rectangular in outline and interpreted in it a number of tadpole-like cranial features, most notably azygous frontoparietals and a sword-like parasphenoid, large otic capsules, a possible spiracle, and possible imprints of a slightly detached beak. A series of small vertebrae extends along the axial column to the end of the tail, and the tail bears what appears to be an anteroposteriorly short, heterocercal caudal fin without any obvious indication of internal supports. No traces of limbs or girdles were reported. Nevo (1964: 107) tentatively suggested the fossil might be a tadpole of the co-occuring anuran Thoraciliacus . Jarvik (1980: 218) explicitly compared the Makhtesh Ramon fossil to Palaespondylus , and used that comparison to bolster his suggestion that the latter was tadpole. Based on figures published by Nevo (1956, 1964) and setting aside his interpretations of its structure, on the basis of its general structure and proportions the Makhtesh Ramon fossil seems more reminiscent of Palaespondylus than of tadpoles, including tadpoles of Thoraciliacus described from Makhtesh Ramon by Roček and Van Dijk (2003). Intriguingly, however, no fish fossils have been reported from Makhtesh Ramon (see Database of Verte-brates: Fossil Fish, Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds (fosFARbase) at www.wahre-staerke.com; accessed 15 May 2016). Another possibility is that the Israeli specimen might be a young larval individual of the salamander Ramonellus longispinus NEVO et ESTES, 1969 , which is known at Makhtesh Ramon by about 16 presumably adult skeletons (e.g., Nevo and Estes 1969, Estes 1981, Gardner et al. 2003, Gardner and Rage 2016). More detailed study of this intriguing Early Cretaceous, tadpole-like fossil is needed to resolve its identity.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Palaeospondylus gunni TRAQUAIR , 1890

| Gardner, James D. 2016 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893: 186 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Palaeospondylus

| , Dawson 1893 |

Dipterus valenciennesi

| SEDGWICK et MURCHISON 1829 |