Gomalia elma elma Trimen, 1862

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4173.4.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3E955EB2-79DE-462C-B3EE-E4AF334D1F61 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5632256 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B14087C8-FF9E-9277-16BA-FCA5FB1504CB |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Gomalia elma elma Trimen, 1862 |

| status |

|

Gomalia elma elma Trimen, 1862 View in CoL

Trimen (1862) described this species from South Africa and it is found in open habitats through Sub-Saharan Africa and Arabia (Ackery et al. 1995). Evans (1937) treated the African material extending as far north as Aden and Arabia as G. e l m a, commenting that the ‘Indian species ( albofasciata)’ has different genitalia. He subsequently treated the Asian population from Yemen ( Aden) to Sri Lanka as subspecies G. elma albofasciata (Evans 1949) . Larsen (1984) then treated the Arabian material as G. elma elma , although he subsequently commented that the ssp. albofasciata hardly differs from ssp. elma (Larsen 1991) . Ackery et al. (1995) recognised both subspecies, and treated the Arabian populations as ssp. elma . More recently, Benyamini (1990b) described ssp. levana from the Dead Sea, Israel.

Picard (1949) described Tavetana jeanneli Picard from Taveta, Kenya, with a good figure of the male genitalia; it is based on a small, dark specimen of G. e l m a elma (Evans 1951) . Gomalia elma elma is widespread in Kenya, and common from the Central Highlands to the coast, wherever Abutilon spp. occur, extending into quite dry areas. Van Someren (1939) reports it from the lower forests of the northern Chyulu Hills up to 1830m ( 6,500 ft.) and Sevastopulo (1974) found it fairly common on the outskirts of Makardara Forest. It probably occurs wherever its food plants ( Abutilon spp.) occur.

Adult behaviour. The adult has a striking resting position (Figure 30.1–2) with the wings held somewhat downwards (more like a moth) and the abdomen tip is curled up and even slightly forwards over the body (see also Henning et al. 1997, p.116). When feeding the wings are held slightly (Figure 30.3–4) or widely open and the white of the hind wing is usually visible. Kielland (1990) says that adults are attracted to mud; I have not seen this, but I have seen them come to fresh donkey dung (Magadi Road, 10 Jun 1990).

Food plants. A variety of Abutilon spp. ( Figure 31 View FIGURE 31 ) have been recorded as food plants. Van Someren (1939) notes that the distribution of G. el m a in the Chyulu Hills is ‘controlled by the distribution of its food plant’ but neglected to mention what the food plant is. Le Pelley (1959) gives Abutilon sp. for Uganda, Van Someren (1974) and Kielland (1990) give A. guineense (= A. guinense ) and A. holstii (an unresolved name, perhaps a synonym of A. angulatum ) for East Africa . Sevastopulo (1974) lists Abutilon mauritianum as the food plant, but in his East Africa list (Sevastopulo 1975) truncates this to Abutilon . Kielland (1990) repeats Abutilon , although Larsen (1991) states that the food plants are ‘various species of Malvaceae especially Abutilon ’. In Kenya I have found this species on Abutilon mauritianum ( sensu lato including var. zanzibaricum ) (Figure 31.2) and A. longicuspe (Figure 31.1). The former is prevalent and used mostly in lower and drier areas while the latter is used in the wetter Central Highlands .

In southern Africa, A. grantii , A. indicum (= A. grandiflorum ), A. sonneratianum are reported (Platt 1921, Murray 1959, Gifford 1965, Dickson & Kroon 1978, Pringle et al. 1994, Henning et al. 1997). Heath et al. (2002) list these and the East African records. Otto et al. (2013) add Abutilon austroafricanum to the known South African food plants. G.C. Clark (in Dickson & Kroon 1978, Plate 18) illustrates the life history.

In Côte d’Ivoire, Vuattoux (1999) found this species on A. mauritianum , Sida cordifolia and Wissadula amplissima . He also reports two specimens reared from Croton zambesicus (which may be a synonym of C. gratissimus ; Euphorbiaceae ), which as Larsen (2005) suggests is ‘rather improbable’ and may reflect a coding or labelling error. In Oman, Abutilon pannosum is used under oasis conditions (Larsen & Larsen 1980), and I have found it on the same food plant in Sharjah , UAE.

Benyamini (1990a) described the life history of ssp. levana on Abutilon fruticosum around the Dead Sea, and Bell (1924) provides a detailed description of the life history of ssp. albofasciata, which develops in five instars on A. indicum in India.

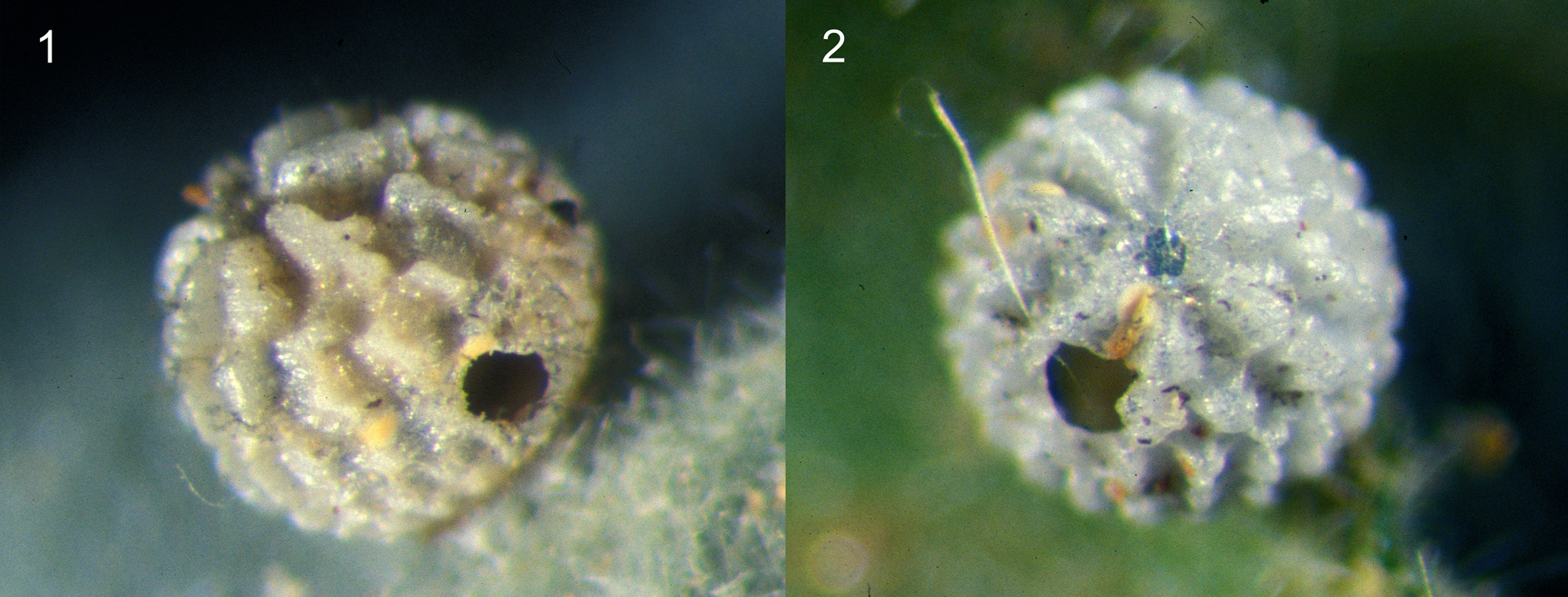

Ovum. The ovum ( Figure 32 View FIGURE 32 ) is laid singly on the leaf upper surface. It is 0.64mm wide at the base (range 0.62–0.66, n=4), 1.03mm at the widest part (range 1.00–1.06, n=4), and 0.83mm high (range 0.80, 0.86, n=2). There are five irregular tiers of cones or short ridges around the ovum, about 23 in the lowest, 12 subdorsally, and seven around the micropyle, which is 0.10–0.14mm wide and surrounded by a low ridge from which the topmost tier of seven short ridges radiate. G.C. Clark (in Dickson & Kroon 1978, Plate 18) illustrates the ovum from South Africa.

Leaf shelters. The shelters of young caterpillars are usually small flaps (about 15 x 6 mm) cut from the edge of leaves and folded over upwards. They will also use small leaves of food plant (at least of A. mauritianum ) folded upwards along the mid-rib (as they are before opening). Larger caterpillars will fold a correspondingly larger flap (Figure 33.2) which is usually folded under the leaf rather than over (one assumes because the paler leaf underside if turned over would be more conspicuous—see discussion under S. ploetzi above). Another large leaf shelter (on A. longicuspe ) involved two nearby folds from the base of the leaf to the margin (Figure 33.1); the caterpillar rested between the two adjacent leaf upper surfaces rather than the two adjacent leaf under surfaces. The pupa may be formed in a simple shelter in a folded leaf or between two leaves. Frequently the leaves which form the pupal shelter are perforated with many small holes, similar to the shelters of Spialia dromus and S. ploetzi .

In July 2001, things were very dry at Kibwezi when I visited; ephemerals and grasses appeared to be mostly dead and only a few small plants of Melhania , Hermannia , Sida etc. were noted. Small ( 10cm) plants of A. mauritianum yielded evidence of early stages of G. elma (MJWC 01/200): a shelter made by attaching two small dead leaves to the underside of one of the larger leaves held an emerged pupa, a final instar caterpillar was in a shelter between several small leaves, and two ova with parasitoid emergence holes were found.

Caterpillar. The caterpillar ( Figure 34 View FIGURE 34 ) is superficially similar to those of Spialia spp., but compared to those Spialia spp. which I have reared it is larger, paler green almost white, the T1 plate is unmarked, and the black head with short white, and longer black setae is not quite like that of any Spialia sp. Collections of early stages from Bénin and Tanzania did not show any differences although measurements are not included in the numbers from Kenya given in this section. In contrast, a collection from Sharjah, UAE, showed some differences and is discussed below.

There are five instars. The final, instar 5 caterpillar grows from 16–20mm when newly moulted to 25–28mm shortly before pupation. The head is 2.5 x 2.6mm wide x high (range 2.2–2.9 x 2.6–2.8, n=7); chordate but flattened at vertex; black, shiny, rugose-reticulate; face covered with sort, erect white simple setae, shorter centrally ( 0.16mm); laterally and dorsally longer, black, erect, slightly barbed setae up to 0.70mm, mostly curved forwards. T1 concolorous with body; mixed short and long, erect, pale, simple setae. Body white with a green tinge; covered with long, erect, white, simple setae; all legs and spiracles concolorous.

Instars 2–4 are basically similar except that in the earlier instars the head is more clearly reticulate, the setae on the head are less conspicuous and the black setae on the head are replaced by dark setae in instar 3 or white setae in instars 2 and 3. The head capsule measurements are given in Table 7 View TABLE 7 . The head of instar 1 is quite similar: brown, shiny, weakly reticulate; a few very short pale, erect setae, mostly bifurcate just before apex. Instar 1 has the pronotum black; a narrow, black transverse bar persists into instar 3, but in instars 4 and 5 T1 is the same colour as the body. The final three instars lasted 12, 11 and 13 (range 7–17) days each.

Kenya UAE

1 i. e. the number of individuals measured (and the number of different collections from which they were taken).

Pupa. The pupa, as shown in Figure 35 View FIGURE 35 , is similar to those of Spialia spp.; 13–15mm long; spiracles A 2 – A 3 partly visible; the proboscis sheath just extending beyond the wing cases; perforated white wax bloom giving a speckled appearance. In Kenya, the colour varies from dark brown with just the appendages translucent and pale ( MJWC 88 /45) to a basically pale, translucent pupa, only tinted brown dorsally ( MJWC 87 /32). The great majority are intermediate, similar to those shown in Figure 35 View FIGURE 35 . The spiracle T1 is similar to those of Spialia spp. above, 0.52 x 0.62 x 0.35 wide x high x deep, but quite variable in size (range 0.44–0.68 x 0.42–0.80 x 0.30–0.40mm, n=4); other spiracles dark and conspicuous depending on surrounding colour; no visible plaques. The pupa takes 15 days to develop (range 12–17, n=4). In the field, a newly emerged adult was observed at about 13:00h ( South Muguga Forest, 31 Oct 1988), and in captivity a 13:30h emergence was recorded.

Life history, United Arab Emirates. I reared G. e l m a from caterpillars collected in the Hattar Mountains at Showkah, which lies within Sharjah, United Arab Emirates (UAE) . The collection was made in an area of fenced (i.e. ungrazed) plantation where just three plants of A. pannosum were present. All plants had several shelters, and most leaves had at least one; two ova and eight caterpillars of instars 2 to 5 were collected, of which six were reared through.

Leaf shelter 1 was an irregularly rounded flap up to 6mm across, cut from the middle or edge of the lamina, and folded underneath along a straight edge. The underside of the section of leaf forming the flap was skeletonised, but not the under surface of the leaf which was covered by the flap, and this behaviour makes the shelter and caterpillar feeding much less obvious from above. Leaf shelter 2 was a larger flap, also cut from mid lamina or the lamina edge, and folded underneath along an edge of about 20mm; the associated feeding perforated the nearby leaf. Shelter 3 was a large leaf fold under the leaf, occupying about one-quarter of the leaf area. None of the shelters were perforated as was often observed in Kenya.

The caterpillars from UAE (Figure 36.1–2) were not significantly different from those documented from Kenya. The head capsules of instars 2–4 are slightly larger ( Table 7 View TABLE 7 ), suggesting different development rates, but the evidence for this is weak. However, there is a consistent difference in the pupae in that those from UAE (Figure 36.3–4) are rather uniformly brown or dark brown, including the wings and other appendages, whereas these areas were pale in all 16 Kenyan examples examined. However, pupae documented from India are also pale (Bell 1924), so this difference in colouring does not align with either of the accepted subspecies, elma or albofasciata. On the other hand, Bell’s (1924) detailed account from India, does not mention perforations of any leaf shelters, which matches what I observed in UAE, but differs from what was regularly seen in Kenya.

Natural enemies. Two ova collected on A. mauritianum at Kibwezi Forest , 29 Jul 2001 ( MJWC 01 /200C, D) had parasitoid exit holes 0.22–0.24mm in diameter ( Figure 32 View FIGURE 32 ), but no specimens have been reared.

Dickson & Kroon (1978, Plate 18) record a braconid larval parasitoid and a Diptera attacking the later stages in South Africa. An unidentified ichneumonoid was reared from caterpillars collected on A. longicuspe at Muguga, and on A. mauritianum at Ndara. It attacks medium grown caterpillars, emerging from the host to spin its cocoon in the host shelter. The ichneumonoid cocoon is 5–6mm long, somewhere between grey, white and brown in colour, with a paler band around the centre (Muguga specimen). It takes 13 or more days to emerge.

Thecocarcelia latifrons , a tachinid larval pupal parasitoid which also attacks Spialia spp. (see sections for S.

spio , S. diomus and S. zebra ), was reared from several caterpillars of G. e l m a collected on A. mauritianum at Arabuko-Sokoke Forest. Adult flies emerged from the host pupae 26, 32, and 37 days after the host pupated.

Discussion. In the Afrotropical context, Carcharodini forms a distinctive and easily recognised tribe of Pyrginae with regard to the early stages (cf. Cock & Congdon 2011a, 2011b). Until recently, they were considered part of the Pyrgus group (Evans 1949, 1953, De Jong 1978), which included the genera Spialia , Gomalia , Alenia , Carcharodus , Muschampia , Pyrgus in the Old World, and Pyrgus , Heliopyrgus , Heliopetes , Celotes and Pholisora in the Americas (see section introducing Carcharodini above). Warren et al. (2008, 2009) found this group to be polyphyletic, and removed Alenia to the Celaenorrhini , and split the remaining genera between two tribes: Carcharodini ( Gomalia , Carcharodus , Spialia and Muschampia in one clade) and Pyrgini ( Pyrgus , Celotes , Heliopyrgus and Heliopetes in one clade).

Almost all genera of these two clades of Carcharodini and Pyrgini include Malvaceae in their food plants ( Table 8 View TABLE 8 ) and the caterpillars and to a lesser extent the pupae are generally similar ( Figure 37 View FIGURE 37 ; Janzen & Hallwachs 2015, Pro Natura 1999, Mazzei et al. 2015, Wagner 2015, etc.), both within and between the two clades. Certainly, the early stages of the two clades show a much greater resemblance to each other than they do to the other clades in their tribes, many of which can be seen on Janzen & Hallwachs (2015) website of Costa Rican Lepidoptera early stages. In contrast, although the caterpillar of Alenia sandaster (Trimen) is quite similar in overall appearance, it has minimal setae on the body and the vestiture on the head differs from that described here for Spialia spp. but aligns with some of the Celaenorrhini , and the pupa has a long proboscis which is also a feature of Celaenorrhini (G.C. Clark in Dickson & Kroon 1978, Cock & Congdon 2011b).

Tribe and genus Main food plants Other food plants Selected references

Carcharodini : Gomalia Malvaceae The present work (and references herein) Warren et al. (2008, 2009) attribute the similarities of these three clades in three different tribes to convergent evolution, referring to the model analysis of Shapiro (1993) which considers two species of Pyrgus , one in the western USA and the other in Patagonia, which are very similar in appearance and habits, but not closely related. The use of semi-arid habitats by many members of these genera may well be a significant factor leading to similar solutions. The use of Malvaceae may be a cause of convergence or a result. In earlier parts of this series, it was suggested that the caterpillars of Hesperiinae species that pupate in an exposed or partially exposed way on Poaceae and Arecaceae have converged on a cryptic pupa—elongate with a frontal spike and green with pale longitudinal lines—which we referred to as Baorini-type, but is found in several tribes of Hesperiinae and in Heteropterinae (Cock & Congdon 2012). The situation with the small chequered skippers discussed here may well be a similar example involving three tribes, although the common advantage is not so clear.

TABLE 7. Head capsule sizes (width x height) for Gomalia elma from Kenya and United Arab Emirates (UAE).

| Instar No.1 | Mean | Range | No.1 | Mean | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 1(1) | 0.70 x 0.74 | 2(1) | 0.69 x 0.76 | 0.64–0.74 x 0.70–0.88 | |

| 2 6(5) | 0.98 x 1.06 | 0.90–1.08 x 0.94–1.24 | 2(1) | 1.04 x 1.22 | 1.00–1.08 x 1.10–1.34 |

| 3 7(5) | 1.40 x 1.49 | 1.20–1.57 x 1.26–1.69 | 4(1) | 1.38 x 1.62 | 1.32–1.41 x 1.44–2.04 |

| 4 8(7) | 1.78 x 1.84 | 1.70–1.88 x 1.74–2.12 | 6(1) | 2.00 x 2.10 | 1.80–2.04 x 1.92–2.31 |

| 5 6(6) | 2.50 x 2.63 | 2.20–2.94 x 2.55–2.71 | 6(1) | 2.54 x 2.64 | 2.35–2.71 x 2.51–2.94 |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Pyrginae |

|

Tribe |

Carcharodini |

|

Genus |