Complicatella neili, Shear & Richart & Wong, 2020

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4753.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:AA9F66B3-EF8C-4F6B-8F35-0BCBEE5122ED |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4341555 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/131D87EF-FF9B-FFAC-FFDC-5E4CFDC1FEF9 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Complicatella neili |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Complicatella neili View in CoL , new species

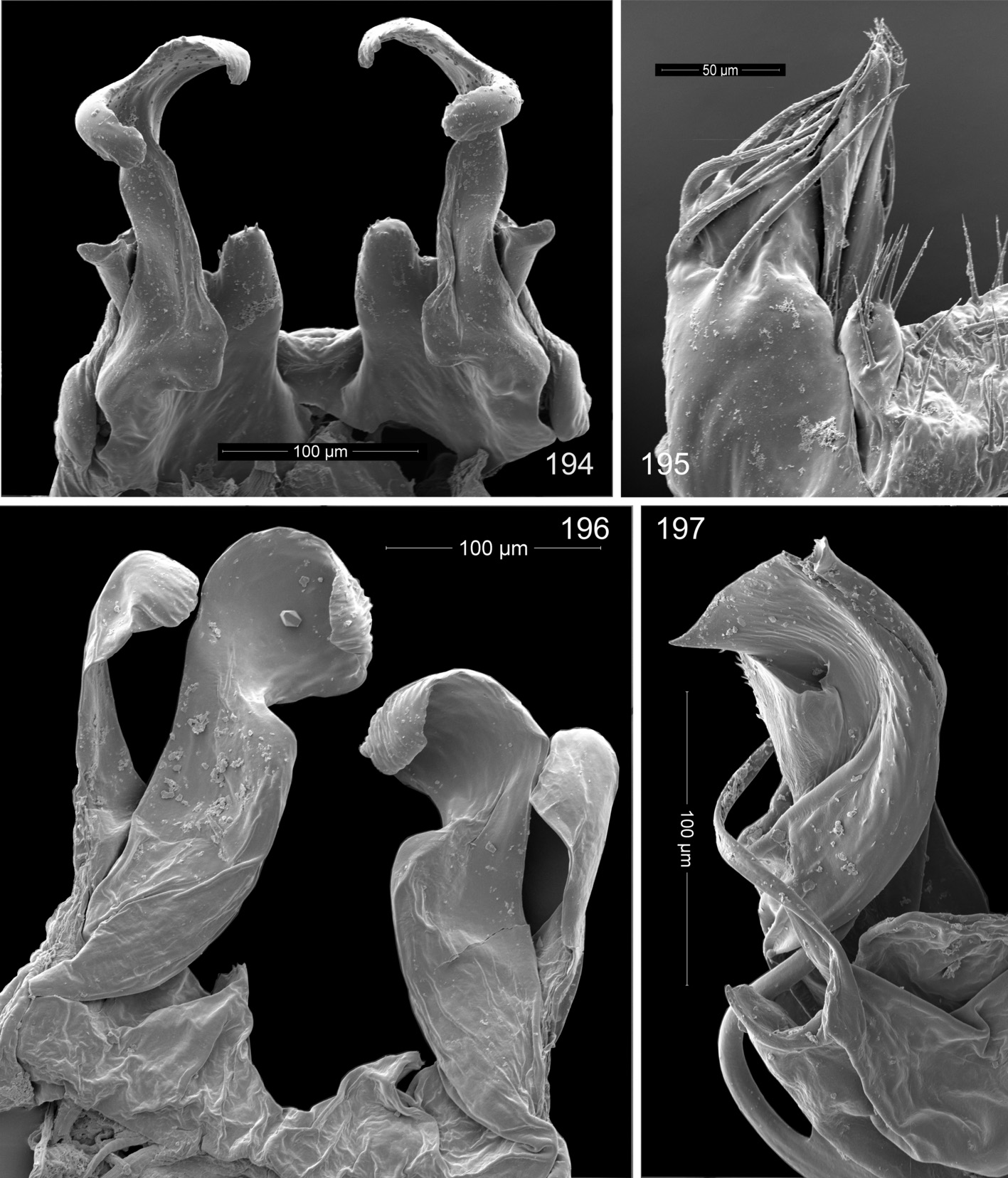

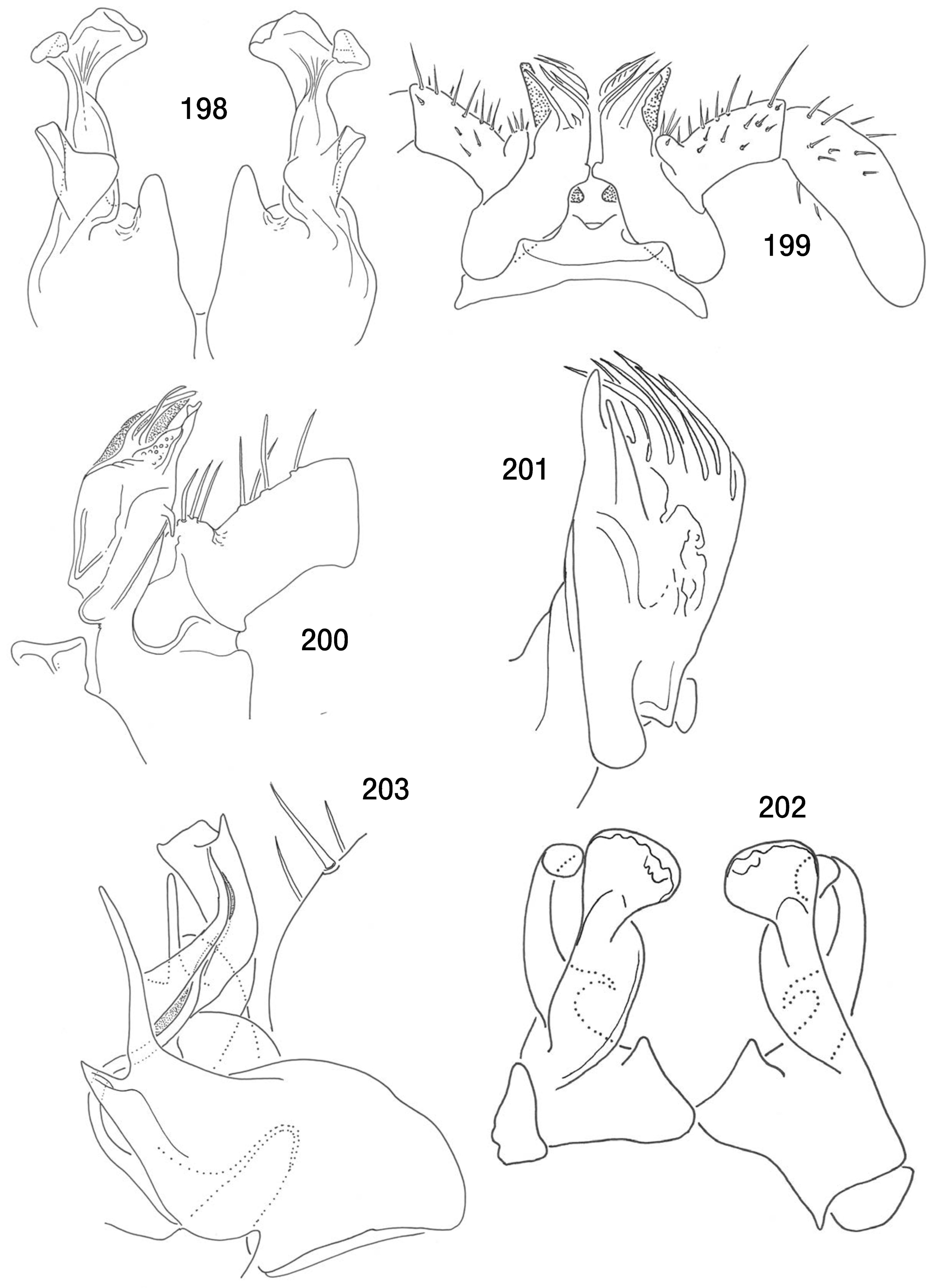

Figs. 196, 197 View FIGS , 202, 203 View FIGS

Types: Male holotype and male and female paratypes from NEVADA: Pershing Co., Dragon’s Gate Cave , elev. 2660 m., 40.5551°N, - 118.1601°W, collected 19 August 2008, by Neil Marchington GoogleMaps .

Diagnosis: Unlike the other two species of Complicatella , C. neili has anterior gonopods with an anterior process that is almost as long as the body of the gonopod. The posterior gonopod coxites have the characteristic basally arising, sheathed flagellum but only two pseudoflagella. The ocelli are poorly formed and metazonital shoulders are practically absent.

Etymology: The species is named for the collector, Neil Marchington, an indefatigable explorer of northwestern caves.

Description: Male holotype: Length, 7.5 mm. Ocelli 13–15 in oblong patch, poorly formed and pigmented (some paratypes have as few as 10 ocelli). Metazonites with no visible shoulders, segmental setae very long, curved, acute. Color white, with some very faint tan shading ventrally on few anterior segments. Legpairs one and two reduced, legpair three enlarged with swollen femur; legpairs four to seven only a little more robust than postgonopodal legs, lacking femoral knobs. Anterior gonopods ( Figs. 196 View FIGS , 202 View FIGS ) strongly clavate, apically cupped distal to distinct shoulder, with clavate, large, anterior branch. Posterior gonopod coxites ( Figs. 197 View FIGS , 201 View FIGS ) complex, body of coxa swollen, long, thin flagellum arises mesally near the base, curving sigmoidally into sheathing branch, two long pseudoflagella present, small pore at base of apical expansion of main branch. Coxa 10 not enlarged, with gland. Prefemur 11 with basal process projecting dorsally.

Female 8.0 mm long, nonsexual characters as in male.

Distribution: Known only from the type locality.

Notes: This species is distant in its location from the others of the genus and its placement may be doubtful. We put it in Complicatella based on the similarities of the gonopods with C. complicata . It was totally unexpected to find a troglobiotic conotylid in the circumstances of the type locality, a barren mountaintop in Nevada in a range surrounded by sagebrush desert. However, its appearance there may be somewhat explained by these habitat notes supplied by Neil Marchington (pers. comm. to WAS, 2018):

“The Nevada specimens, collected 19 Aug 2008, came from a small cave called Dragon’s Pit in the Humboldt Range of Pershing County, Nevada at 8682 feet elevation. The specimens were clinging to a soft, wet calcite paste on the ceiling of the cave about 60–80 feet from the entrance. The cave is 105 miles NE of Reno or 35 miles SW of Winnemucca. The cave is on a nearly barren limestone peak with scattered sage, gooseberry, rice grass and (strangely) stunted mountain maple. There are stunted juniper growing about 700 feet lower in elevation than the cave. The Humboldt Range was likely nearly an island during the Pleistocene. The projected levels of glacial Lake Lahontan show only a narrow land bridge at the south end of the range connecting to any other land. The confirmed and studied shoreline puts at least 50% of the range as a shoreline area (the west and north sides were for sure).”

“The climate history of the region can be summarized fairly easily. About 4 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada Range started to rapidly uplift forming a massive fault block. The peaks started increasingly taking more of the Pacific moisture. This process led to the massive desert regions such as Carson, Great Basin and Mohave. The Ice Age’s lower temps allowed the water that did get through to exceed evaporation in the Great Basin and Mohave. Giant lakes like Lahontan filled most of the basins, and crept over modern passes, forming vast waterways surrounding many mountain ranges entirely. The Humboldt Range was a giant island in this lake. We know from archaeological sites the region had vast marshlands where the natives hunted ducks and other animals. Tule reeds were used in many native artifacts, such as duck decoys, baskets, and sandals. Many of the higher peaks were glaciated, particularly the eastern Sierra Nevada.”

“Around 14,000 years ago, the Wisconsin Glaciation was waning. As temperatures rose, the basins gradually started to lose water each year. There were at least pockets of ice age megafauna, such as short-nosed bears, lurking in the mountains as recently as ~8000 years ago, but most of the population was probably gone around 10,000 years ago. The desertification of the area seems to be continuing and possibly accelerating. There are studies monitoring plant communities moving to higher elevations in the region. Most of the Ponderosa groves in Nevada are of 200-year-old trees, with nothing younger present. Even 500 years ago, Ponderosa were growing in lower areas in the Mohave, where only cacti grow today. Douglas Fir cones have been found in 30,000 year old middens throughout areas of Arizona, Nevada, and Utah where there are only cacti or juniper today.”

The geological and climatic history of Lake Lahontan is summarized in Morrison (1963).

So the clear suggestion is, as with so many other arthropods now limited to caves, that the ancestors of the present population lived on the surface during a moist glacial maximum, and were also able to occupy caves. With the drying and warming starting 140 centuries ago, surface populations were gradually extinguished, leaving only those in the hospitable, buffered environment of the caves. Subsequently the remnant population developed the modest troglobiotic adaptations we see today.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Heterochordeumatidea |

|

SuperFamily |

Conotyloidea |

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Conotylinae |

|

Genus |