Attavicinus monstrosus (Bates), 2008

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1649/984.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D687D5-C271-A537-5849-FADBFC28FE1C |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Attavicinus monstrosus (Bates) |

| status |

comb. nov. |

Attavicinus monstrosus (Bates) View in CoL new combination

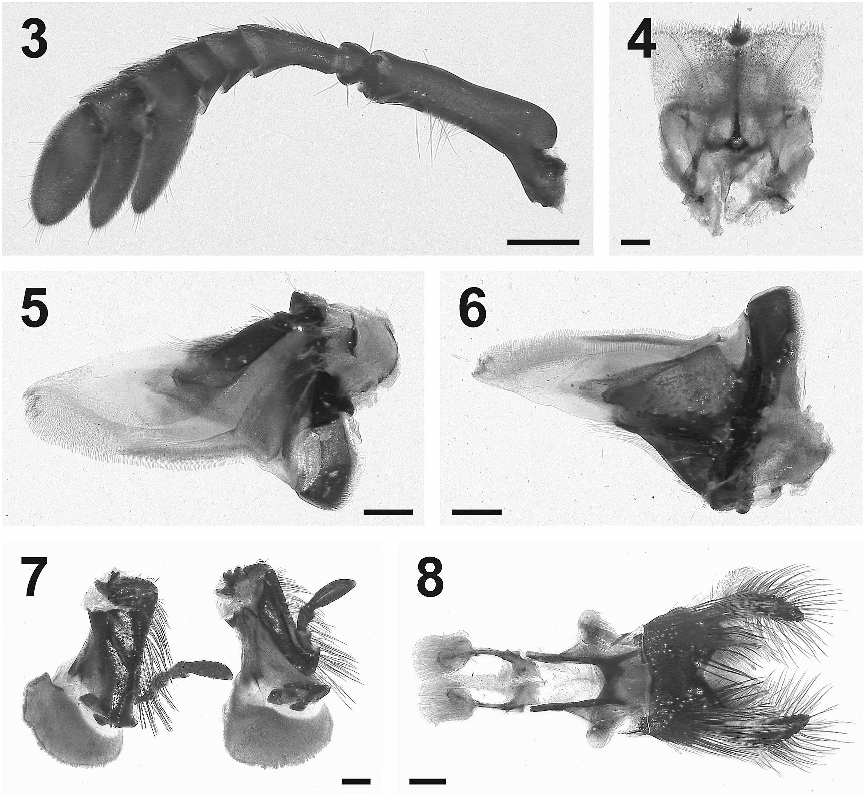

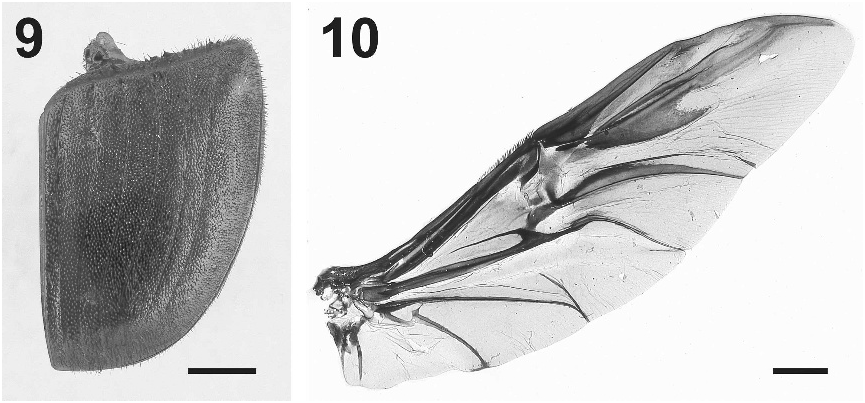

( Figs. 1–16 View Fig View Fig View Figs View Figs View Figs View Fig )

Oniticellus monstrosus Bates, 1887 View in CoL . Type locality: Jalisco, Mexico.

Oniticellus monstrosus Bates, 1887 View in CoL : Bates 1889 (biology); Blackwelder 1944 (catalog);

Liatongus monstrosus: Halffter and Matthews 1966 View in CoL (biology); Halffter 1964 (biology, distribution); Edmonds and Halffter 1972 (larval and pupal description); Anduaga et al. 1976 (biology); Halffter 1976 (distribution); Edmonds and Halffter 1978 (larval classification); Halffter and Edmonds 1982 (nesting behavior); Zunino 1982 (evolution); Márquez-Luna 1994

72 ( Atta View in CoL nest association); Rivera-Cervantes 1995 (distribution); Navarrette- Heredia 1996 (distribution).

Diagnosis. Males and females are easily distinguished from all other New World dung beetles by the large, robust body shape, and the very distinctive cephalic and pronotal sculpture on each sex ( Figs. 1 View Fig and 2 View Fig ). Currently it is only known from the states of Jalisco and Michoacán, Mexico .

Type material. Not seen, but presumably located in the Museum of Natural History in Paris (Musée National d’Histoire Naturelle).

Redescription. Length approximately 15–20 mm ( n 5 5). Black to dark reddishbrown in color. Setae on head and anterior half of pronotum about 2X as long as those on posterior K of pronotum and elytra.

Head strongly punctured and evenly covered with setae; canthus separating lobes wide, eye dorsally small, hemispherical to triangular in shape, much larger ventrally. Setal fringe around perimeter ventrally, near but not at smooth margin, fringe exposed in dorsal view at postero-lateral margin, at middle small broad ventrally projecting tooth, not visible from above.

Male. Clypeus broadly rounded, distinctly reflexed dorsally, particularly at middle half; genae posteriorly abruptly perpendicularly angled inwards; at middle with small, slightly raised, shining patch anterior of horn; dorsally with moderately coarse, evenly spaced setaceous punctures, apical margin bare; at middle near posterior margin with a short horn, broad at base, then parallel sided beginning at approximately midpoint, surface smooth and impunctate except at base.

Female. Clypeus more narrowly rounded than in male, margined but not reflexed; a transverse ridge at anterior 2/5, extending in length laterally as far as eyes, broadly angulate anteriorly at middle, a second ridge between eyes angles posteriorly more strongly than ridge at anterior 2/5, laterally rising anterodorsally and forming a blunt lobe on each side, each lobe about 2X height of anterior ridge. 74 Pronotum with setose punctures smaller and denser than those on head. Posterior margin with a slight broad lobe at middle. Longitudinal ridges along pronotum approximately aligned with fifth elytral stria at their dorsal peak, slightly converging towards posterior.

Male. Pronotal longitudinal ridges blunt-edged their entire length, in dorsal view from anterior to posterior abruptly dipping downwards obliquely to near lateral margin, in lateral view extending anteriorly as a truncate, squared projection, dorsal edge with small tufts of setae, margin not straight but slightly irregular, posteriorly extending and decreasing in height, curving inward slightly to end near third elytral stria; disc slightly depressed medially. Minor male with much less pronounced and more parallel sided ridges in dorsal view, laterally appearing more rounded than those of the major male.

Female. Pronotal longitudinal ridges extending slightly on posterior K, anteriorly extending forwards as a pair of short, blunt lobes, a third blunt lobe projecting anterodorsally at middle; before each lateral lobe a small shallow concavity about as wide as base of each lobe, anterior to this a second concavity about half the diameter of the first.

Scutellum small but visible with pronotum fully extended posteriorly, elongate triangular in shape, approximately equal in width to first elytral interval.

Elytra ( Fig. 9 View Figs ) with seven striae visible for entire length in female, seventh ending about middle of elytra in male, surface finely granulate, covered with dense, evenly distributed, short, suberect, blade-like setae, each arising from slight posteriorly angled surface projection forming a papilla.

Ventral surface ( Fig. 15 View Figs ) with moderately dense, setose punctures, less numerous at posterior and middle of metasternum; pro- and mesocoxae with finer punctures, metacoxae smooth except posterior margin punctate. Prosternum with a distinct, broad, median ridge at posterior margin, extending anteriorly as a narrow sharp-edged ridge between procoxae. Abdominal ventrites 3–6 slightly shorter and more curved than abdominal ventrites 1–2. Pygidium with punctures similar to head and covered with fine, short setae.

Male genitalia ( Fig. 13 View Figs ) with apex blunt, parameres with small sharp projections near apex.

Distribution. This species is known from several areas in Jalisco and Michoacán, Mexico ( Fig. 16 View Fig ). While hypothesized to occur in the adjacent state of Michoacán by Navarrete-Heredia (1996), B. Kohlmann (pers. comm.) collected the species there many years earlier in Cojumatlán de Régules, near the border of Lago de Chapala. Further Jalisco state records of his include Jocotepec, San Luis Soyatlán and Mezcala, also all around the border of the lake.

Published records include Los Guaybos (east of Lago Chapala) in the east near the Michoacán state border to the western part of the state at El Portezuelo. It has also been collected just north of Guadalajara at Barranca de Oblatos and in the southern part of the state near the Colima state border in the Sierra de Manantlán. For a full locality list see Halffter (1964), Halffter (1976), Rivera- Cervantes (1995), and Navarrete-Heredia (1996).

Comments. The female, compared to the male, is the more ornately armored of the sexes with the possession of extra ridges and projections on the head and pronotum. This characteristic may have evolved through selection of females for guarding and defending nest resources from intraspecific individuals (Emlen and Philips 2006). Additionally, they likely have to defend their nests against other species, as there are both a wide variety of beetle species that use attine ant nest debris for feeding and larval rearing (Márquez-Luna 1994) and other potential non-beetle predators.

Biology

Nest Habitat. The close association of A. monstrosus with ants was first noted by Bates (1889) and later confirmed by Halffter (1964) with his record of larvae and adults within the nest debris pile. These beetles are only known from the nests of A. mexicana . They could be considered either tolerated guests or neutral synoeketes based on a classification of ant nest guests first proposed by Wasmann (1894). Typically they live without any direct contact with the ants, feeding in superficial ant debris chambers which overflow to the surface. This lifestyle is a specialized form of saprophagy and is relatively rare in the scarabaeine dung beetles. The debris pile is composed of spent fungal garden debris and small pieces of leaves and twigs, together with pieces of ants and other insects. The mounds can reach a depth of over 30 cm and typically have a gradient of moisture that forms very rich humus.

In addition to A. monstrosus , there are a number of other species that exploit this resource, including species of scarabaeines in the genera Ateuchus Weber , Deltochilum Eschscholtz , Onthocharis Westwood , Onthophagus Latreille , Scybalophagus Martínez (as Pseudoepilissus Ferreira) and Scatimus Erichson. Currently , Ontherus cephalotes Harold is the only scarabaeine that has been found in the actual fungal chambers of the ants (Halffter and Matthews 1966; Márquez-Luna 1994). Additional beetles found in the debris include cetoniines, passalids, tenebrionids, histerids, and staphylinids.

Nidification. The adults and larvae were mistakenly reported by Halffter and Matthews (1966) to be free-living in the ant nest debris and that this species had lost complex behaviors associated with nesting as typically found in dung beetles. Free-living larvae ( i.e., not within a brood ball, pear, or sausage) are rare but have been reported for species in the Scarabaeus Linnaeus subgenus Pachysoma MacLeay that feed on buried dung or plant detritus ( Harrison et al. 2003; Scholtz et al. 2004) as well as some dung-feeding Onitis Fabricius and Onthophagus and species of Drepanocerus Kirby and Trichillum Harold (Halffter and Matthews 1966) . This may also be true within the eucraniine dung beetles that have similar biologies to that of Scarabaeus subgenus Pachysoma ( Ocampo 2004; Ocampo 2005; Ocampo and Philips 2005).

Further reports by Halffter and Edmonds (1982), Halffter (1976), and Anduaga et al. (1976) corrected these erroneous statements. Hence, A. monstrosus does not have a free-living larva but is a ‘‘pattern 1’’ nester according to Halffter and Edmonds’ (1982) classification of dung beetle nidification behaviors. Beetles of this type construct compound nests, and cooperation between the sexes, or at least an increased tendency for this behavior, is typical. Halffter and Edmonds (1982) give an excellent description of nesting behavior in A. monstrosus . In this species, there is usually a primary tunnel with as many as five side branches recorded. Tunnels generally extend about 50 cm deep but have been recorded as much as 80 cm in depth. The female typically packs each blind branch or burrow with detritus and constructs individual, but poorly defined, egg chambers along the cylindrical sausage provision. An egg is laid roughly every 10 cm from, but not at, the distal end of the sausage. There is no physical separation of the brood masses into separate forms in the shape of balls or pears. Usually there are one to three eggs laid in each detritus-filled side branch. As many as 11 eggs have been found in a single nest. Up to now all nests have only been found under debris chambers located under tree shade (B. Kohlmann, pers. comm.).

The role of the male is unclear and might be relatively minimal as females are typically found alone. Similar to other type 1 nesters, the male may be restricted to delivering ant nest detritus to the female at or near the nest entrance.

76 Larval characteristics. Attavicinus monstrosus larvae were described by Edmonds and Halffter (1972). Additionally, a summary of larval features for the genus Liatongus (but based on A. monstrosus ) is given in Edmonds and Halffter (1978). Larvae are characterized by the flattened sensory area of the third antennomere and the dorsomedial prominence on the third abdominal segment as well as other characters (Edmonds and Halffter 1978). An earlier report (Halffter and Matthews 1966) of larvae lacking a hump was in error.

Pupation. A pupal description for Attavicinus is given in Edmonds and Halffter (1972). The pupal chamber is among the most elaborate known in the scarabaeine dung beetles (Halffter and Edmonds 1982). The chamber shape is tubular with one end rounded and the other end flattened with a round, flat lid. Construction occurs via successive depositions of rings of excrement that are visible on the external surface. As in many other dung beetles, if the integrity of the chamber is compromised, repair immediately occurs via feces deposition into the opening. The adult emerges by pushing off the chamber lid. Dead pupae have been found in the field with nematodes inside their body cavities. It is not known if the pupae died because of a nematode attack, or if they were ‘‘colonized’’ after dying (B. Kohlmann, pers. comm.).

Flight Behavior. Males and females have been observed flying early in the morning (8–10 am) at approximately half a meter in altitude, searching for ant nest debris (B. Kohlmann, pers. comm.). The flight pattern is in the shape of a ‘‘figure eight’’ and is similar to that seen in species of Phanaeus . After the ant nest debris odor is detected, beetles fly straight in and land on top of the pile.

Evolution of the association with ants. It is interesting to speculate on why this species (and some other dung beetles) breed solely in association with Atta nest debris piles. Halffter and Matthews (1966) propose that it may be a way of improving survival in an unsuitable environment, perhaps due to aridity or some other factor. They also note that ‘‘it [the attine ant debris pile] has clearly provided a refuge for a relict species.’’ As perhaps implied, it is possible that this fairly large-bodied species of ‘‘relict’’ beetle originally fed on dung from one or more of the larger mammal species that once inhabited North America since the Eocene but subsequently went extinct in the Pleistocene. Based on phylogenetic evidence (Philips unpublished and see below), it is apparent that A. monstrosus does represent a relatively old lineage of Oniticellini and so can be considered a relict species within the tribe. There is also little doubt that ancestrally this lineage was a dung feeder. While some large-bodied New World species, such as those within the genera Deltochilum or Dichotomius Hope still feed on dung, the Attavicinus lineage made a switch to feeding on nest debris.

Alternatively, if the switch to ant debris occurred before the Pleistocene vertebrate extinctions and assuming fresh dung was not limiting, what was the selective force? In this case it seems as though aridity could have been a factor in the evolution of a novel nesting behavior in this lineage. The climate in Jalisco is temperate to hot and sub-humid and annual rainfall is generally about 1,000 – 2,000 mm ( Améndola et al. 2005). Currently, there is a four to six month dry season, especially prevalent on the Pacific coast, in winter. Hence, adult and larval survival may be increased beneath relatively moist attine ant debris piles. Adults avoid the dry season and only emerge after the beginning of the rainy season and the evidence indicates only a single generation per year (Halffter and Edmonds 1982).

There is also a distinct possibility that the large body size of this species resulted from selection pressure due to competition within the confined piles of ant nest debris and not from tunneling under dung piles and subsequent dung resource defense. Debris piles represent a valuable resource that can be more easily defended by these heavily armored beetles (see Emlen and Philips [2006] for details on the evolution of horns in tunneling dung beetles). Regardless, evidence for the selective pressure for the type of food source and morphology and the time period when this lineage switched from dung to ant debris feeding may be difficult to discover.

One aspect that is puzzling is why this taxon has such a restricted range, compared to the distribution of the host ant A. mexicana . While the ant is found from Arizona south through El Salvador and Honduras (Hölldobler & Wilson 1990), the beetle is known only from a small area in Mexico. If the limited range of this species is truly real, it would be interesting to find evidence for the cause.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Attavicinus monstrosus (Bates)

| Philips, T. Keith & Bell, Karen L. 2008 |

Attavicinus monstrosus

| Philips & Bell 2008 |

Attavicinus monstrosus

| Philips & Bell 2008 |

monstrosus :

| Halffter and Matthews 1966 |

Oniticellus monstrosus

| Bates 1887 |

Oniticellus monstrosus

| Bates 1887 |

Atta

| Fabricius 1804 |