Agrionemys, Khozatsky & Mlynarski, 1966

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5252/geodiversitas2020v42a22 |

|

publication LSID |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:07001ACA-EBDE-4256-BCB9-55E3159F81DC |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4488520 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CB2D87E1-2E34-FFC9-FBE3-45D4FBC3F82D |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Agrionemys |

| status |

|

Agrionemys sp.

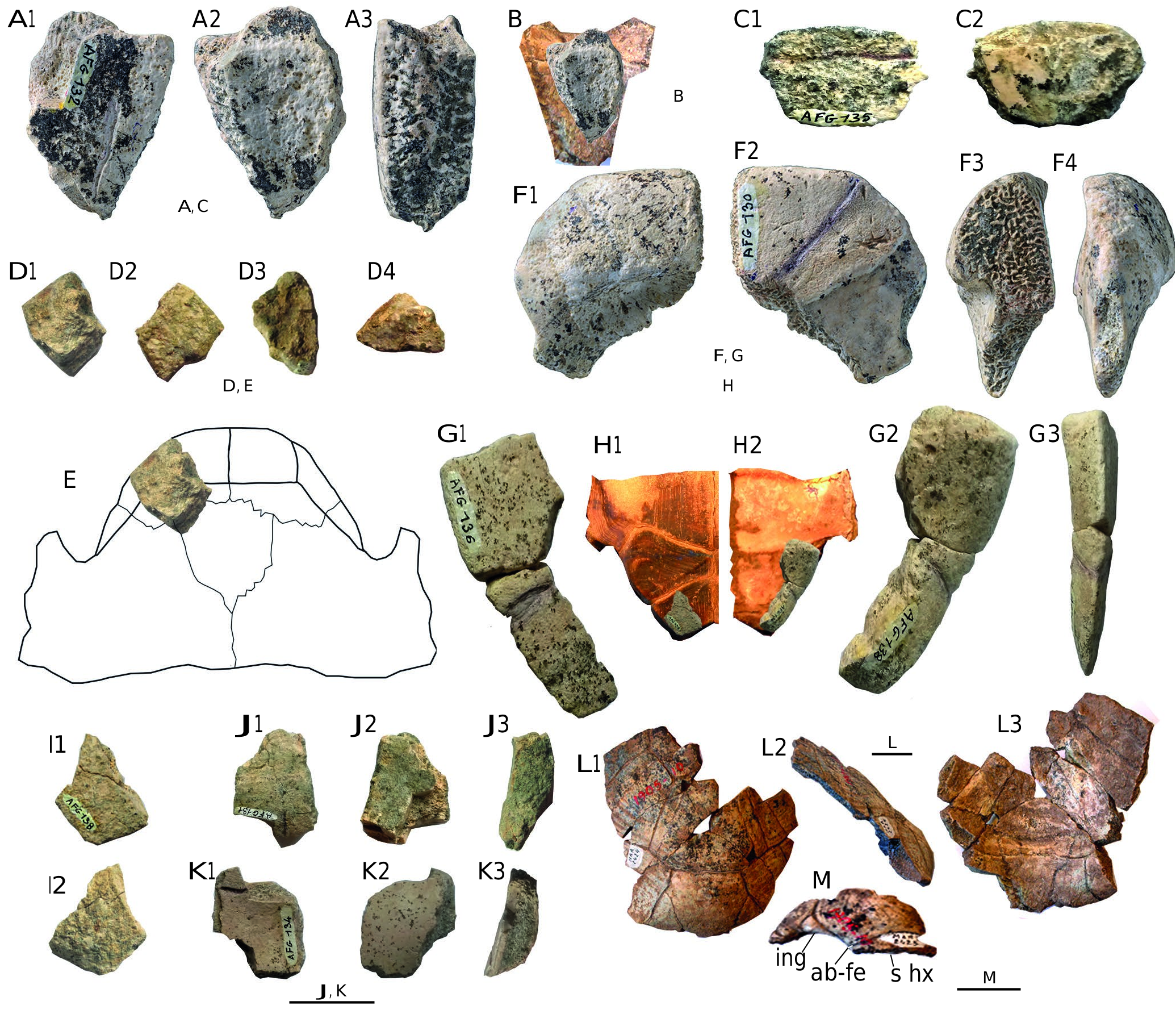

( Fig. 3 View FIG )

LOCALITY AND AGE. — Sherullah 9, Khordkabul basin, Afghanistan, late Miocene, late Vallesian-basal Turolian transition. MN10/11.

MATERIAL EXAMINED. — AFG 130, left epiplastron ( Fig. 3F View FIG ); AFG 131, peripheral plate, fragment without distal border ( Fig. 3J View FIG ); AFG 132, pygal plate fragment ( Fig. 3A View FIG ); AFG 133, peripheral plate, fragment with free border; AFG 134, peripheral plate, fragment ( Fig. 3K View FIG ); AFG 135, neural 5 ( Fig. 3C View FIG ); AFG 136 [+ 138 (10)], fragmentary right xiphiplastron ( Fig. 3G, H View FIG 2 View FIG ); AFG 137, plate fragment; AFG 138 including 10 specimens: 138(1) and 138(2), peripheral plate fragments with preserved distal border; 138(3), peripheral plate fragment without the border; 138(4) (5) (6) (7) (8), plate fragments; 138(9), fragmentary left epiplastron ( Fig. 3D View FIG ); 138(11) fragment of a xiphiplastral anal part ( Fig. 3I, H View FIG 1 View FIG ).

DESCRIPTION

The specimens belonged to several individuals of moderate size (shells c. 17-19 cm long). The fragmentary right xiphiplastron AFG 136 (+ 138[10])( Fig. 3G, H View FIG 2 View FIG ) (4.4 cm long) belonged to a plastron of the size of an extant Agrionemys horsfieldii (Gray, 1844) (specimen REP 59) from Molayan, Khordkabul basin of Afghanistan [“ Kabul, Afghanistan ”, being the type locality of the living species ( Iverson 1992)], which is 15.7 cm long, and it was barely smaller than the plastron of the epiplastron AFG 130 ( Fig. 3F View FIG ) (3.2 cm wide). The left epiplastral fragment AFG 138(9) ( Fig. 3D View FIG ) is barely larger than AFG 130. The fragment of xiphiplastral anal part

AFG 138 (11) seems to have belonged to an individual as large as the fragment AFG 136 (138[10]) ( Fig. 3H View FIG ). The neural 5 ( Fig. 3C View FIG ) corresponds to a dorsal shell of an A. kazachstanica Čhkhikvadze, 1988 View in CoL specimen (MNHN.RA) of 17. 3 cm long, also corresponding to the plastral length of REP 59 and xiphiplastron AFG 136. It was from a slightly smaller individual than the pygal AFG 132 (this maybe of a carapace long of 18.5-19 cm).

The texture of the bones is typical for testudinines: the external surface is apparently relatively smooth with minute points and small granulations. The morphology of the best preserved scute sulci is also typical for testudinines: a fine acute groove limited on each border by a crest, which is especially clear on AFG 130 ( Fig. 3F View FIG 2 View FIG ) for the gularo-humeral sulcus.

Most of the fragments do not provide any particular information within testudinines; their identification is inferred from their conjunction, the best preserved ones being figured, conforming to the genus Agrionemys .

The neural is a neural 5, short, wider than long, hexagonal. It has short sides in front and anterior borders wider than posterior borders. It is anteriorly transversally crossed by the sulcus between vertebrals 3 and 4, at the level of its smaller anterolateral sides. The preserved peripherals are all broken. The plates are massive, thick for their length. Two of them are figured (AFG 131, Fig. 3J View FIG and AFG 134, Fig. 3K View FIG ). They are slightly dorsally incurved, being posterior peripherals, probably the 9 th and 10 th. The fragmentary pygal (AFG 132, Fig. 3A View FIG ) is long, thick, slightly convexe ( Fig. 3A3 View FIG ) from right to left and concave interiorly, apparently being from a male ( Fig. 3A View FIG 2 View FIG , B). The unique supracaudal inner overlap is very long, nearly reaching the suprapygal-pygal suture, as in Agrionemys living specimens and in a Maragheh fossil specimen ( Iran, Turolian) (Maragha in Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006b, c). In the Fig. 3B View FIG , the fossil Afghan partial plate is superposed on the fossil Maragheh pygal

The left epiplastron AFG 130 ( Fig. 3F View FIG ) is slightly broken, missing a small posterolateral angle at the suture with the hyoplastron. Its posterolateral external surface part is smooth due to a worn surface, then artificially limited by a line nearly parallel to the gularohumeral sulcus. The specimen is relatively wide for its full length. Its anterior border is transversal, with a wide gular border which is barely protruded anteriorly to the humerals. The oblique inclination of the specimen lateral border indicates the anterior lobe was trapezoid. The lateral borders are moderately converging, as in the drawing of the Fig. 3E View FIG (drawn on the specimen REP57 of extant A. horsfieldii from Khordkabul basin) and not rounded. The dorsal epiplastral lip is wide, slightly shorter than wide anteriorly, dorsally convex and thick ( Fig. 3F View FIG 1 View FIG , F 3 View FIG , F 4 View FIG ), and it rather abruptly overhangs the posterior epiplastral surface, with a very minute gular pocket, anterior to the entoplastral suture ( Fig. 3F View FIG 1 View FIG , F 3 View FIG ): the wider than long posterior lip border is convex and ends in front of the entoplastron. Ventrally, the gular scute is as long as wide and it was barely prolonged on the entoplastron. The gular is not anteriorly protruding and its surface does not protrude in relation to the humeral. The gularohumeral sulcus is straight, not being anterioly slightly incurved, as it is sometimes the case on one side in Chersine and in living Agrionemys . On the whole, the anterior lobe of AFG 130 was not wide on each side of the wide entoplastron and not much anteriorly narrowed. The other left (fragmentary) epiplastron AFG 138(9) ( Fig. 3E View FIG ) is a fragment at the boundary of the gular and the humeral, at the lateral beginning of the dorsal epiplastral lip: it is thick, and the lateral beginning of the dorsal lip shows it was well elevated anterior to the entoplastron ( Fig. 3D3 View FIG ) and perhaps the gular was more anteriorly protruding than in AFG 130; the anterior lobe borders were more anteriorly converging than in AFG 130. The xiphiplastron AFG 136 ( Fig. 3G View FIG ) is preserved by the lateral part only. It is anteriorly limited by the hypoxiphiplastral suture which was not transformed in a hinge. It is referred to testudinines by the strong dorsal elevation of the bone below the dorsal overlap of the femoral, much raising from the external border towards the inner scute limit ( Fig. 3G View FIG 2 View FIG ), and from the posterior extremity up to the hypoxiphiplastral suture ( Fig. 3G3 View FIG ); this elevation had to follow on the hypoplastron to end in the inguinal notch without a hinge. The xiphiplastral posterior anal extremity is angular (95°). Associating the two xiphiplastral extremities (that of AFG 136 and that of AFG 138[11]), which are convenient for a same individual size, the anal notch was a wide and short triangle: this is shown when superposing ( Fig. 3H View FIG ) these two specimens on the xiphiplastra of the extant Agrionemys horsfieldii (specimen REP 57) of Khordkabul basin. The xiphiplastral had to be approximately anteriorly as wide (at hypoxiphiplastral suture) as long (medially), with lateral borders much converging to the anal notch, as in living Agrionemys . As in Agrionemys , the anal scute ventral overlap was less long than the femoral overlap part on the xiphiplastron.

COMMENTS

The specimens clearly show that the turtle from Sherullah 9 belonged to the group of Palaearctic terrestrial testudinids, the Testudininae , integrated in the past in the waste basket genus “ Testudo Linnaeus, 1758 s.l. ” (as in Broin 1977). The group includes the living – Testudo (s.s.), type-species T. graeca Linnaeus, 1758 , – Chersine Merrem, 1820 , type species Testudo hermanni Gmelin, 1789 [or Eurotestudo Lapparent de Broin, Bour, Parham & Perälä, 2006 (see Bour & Ohler 2008)] and Agrionemys , type species Testudo horsfieldii Gray, 1844 (see Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c) (among which genus are notably the species A. horsfieldii and A. kazachstanica ) ( Iverson 1992). Western fossil species were included in Testudo (s.l.) among which those attributed to the fossil genus Paleotestudo Lapparent de Broin, 2000 . This has for type species Testudo canetotiana Lartet, 1851 from the middle Miocene of Sansan ( France). Sherullah 9 material is here particularly compared with living specimens (REP and MNHN.RA coll.). It is also compared with fossil material from Maragheh ( Iran, MNHN.F. MAR2424, MAR2425, 1905-10 coll.), late Miocene, early Turolian. This is approximately of the same age as Molayan ( Sen 1998). Maragheh material has been attributed without comments to Agrionemys cf. bessarabica Riabinin, 1918 in Lapparent de Broin et al. (2006b , c) and it is confirmed here as being at least an Agrionemys sp. Sherullah 9 material was already mentioned as belonging to Agrionemys in Lapparent de Broin et al. (2006b , c) (without description). During the late Miocene, the testudinines are well diversified in the Eurasiatic area in the three genera Testudo , Chersine and Agrionemys (see Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c). Testudo is distinguished from both others by the derived presence of a hinge between the xiphiplastron and the hypoplastron, in males as in females, with a longer posterior lobe only composed of the xiphiplastra, being narrower with less converging lateral borders. Here, the xiphiplastron AFG 136 is clearly not hinged as in Agrionemys and Chersine . Agrionemy s has a rather wide posterior lobe at inguinal notches, as Chersine , eventually wider according to the species and subspecies and sex, and this conforms to Sherullah 9 partial xiphiplastron ( Fig. 3H View FIG ); in conjunction with the wide posterior lobe at its base, the shape of the carapace of living Agrionemys is wide. It may be wider for its length according to the species or subspecies and sex but, on the whole, it is wider than in Testudo . This cannot be confirmed for Sherullah 9, the carapace plates being too poorly preserved, but the xiphiplastra are congruent for this greater width. Furthermore, Agrionemy s has a short dorsal gular lip anterior to the entoplastron and the gular pocket is always slight, as in Sherullah 9 specimens. Although also anterior to the entoplastron, the epiplastral gular lip is variably long and deep in Chersine (such a variability being known in Plio-Pleistocene Ch. hermanni spp. - subspp. group, in Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c). In Testudo , the pocket is most often larger and overlapped by a long dorsal epiplastral lip, often extending over the entoplastron. The discriminant character of Chersine is a derived secondary division of the supracaudal scute, either only dorsally or only ventrally (in fossil species and subspecies) or both dorsally and ventrally in living representatives. The pygal from Sherullah 9 AFG 132 does not share this character: there is only one supracaudal as in Testudo and Agrionemys ( Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c).

Conforming to Agrionemys : the neural 5 AFG 135 conforms to that observed in extant compared Agrionemys spp. specimens. It is either shorter for its width and/or more hexagono-trapezoid and less rectangular or quadratic than in Testudo and Chersine observed specimens. However, the sulcus V3-V4 position is variable and here it is anterior to the middle length. The pygal is relatively long, according to males of Agrionemys (but also in males of Chersine ) but it is much thicker than in living specimens. The single supracaudal ventral overlap of AFG 132 is long as in Agrionemys male specimens ( Fig. 3B View FIG : AFG 132 pygal superposed on Maragheh pygal). The lateral borders of the plastral lobes are more or less convex in Agrionemys , including the straighter condition of Sherullah 9. In the living species, the anterior lobe is always wide at its base (in relation to the wide carapace) but it may be more or less anteriorly narrowed and protruding at gular lip: there is a bony shape variability which is not yet clearly defined in its relation to sex, individual and speciation. The epiplastron AFG 130 indicates an anterior lobe with moderately converging lateral borders anteriorly, and it is anteriorly straight with wide gulars but without a protruding lip in relation to Agrionemys specimens. However, AFG 138(9) gulars might have been slightly protruding in relation to humerals at least as in some living specimens ( Fig. 3E View FIG ). The lateral posterior lobe borders of AFG 136 are barely rounded with a small femoroanal indentation as in the specimen of A. horsfieldii of Khordkabul basin REP 57. AFG 136 is superposed on extant REP 57 in Fig. 3H View FIG , this being presented with its scutes: the scutes are visible lateroposteriorly exceeding the bone, in black. Sherullah 9 AFG 136 and 138(11) share with A. horsfieldii a short and straight anal notch. Other characters which can allow Agrionemys and Chersine to be distinct from Testudo , such as femur trochanter junction ( Lapparent de Broin & Antunes 2000) are not represented here. Similarly discriminant, but not fully preserved here, is the carapace shape which is rounded and wide in living Agrionemys , and which is particularly short for its length in known A. horsfieldii specimens (type species of the genus). Also discriminant is the fact the Agrionemys shell is much higher than in Chersine and Testudo , with a higher bridge and a more elevated anterior lobe extremity. However, the shell is lower in A. horsfieldii than in A. kazachstanica ( Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a: fig. 11c).

Testudo and Chersine lineages have a more western distribution (around Mediterranean countries; Chersine being only European) compared to living Agrionemys which ranges from Georgia to western Xinjiang (eastern China) and is mostly present in eastern Asia ( Iverson 1992; Rhodin et al. 2017). The three lineages have been separated for a long time. Testudo (s.s.) is diversified since the late Miocene, being present in the Vallesian of Greece at the locality “Ravin de la Pluie” [MN10] ( Garcia et al. 2011) and the Tortonian of Greece (Gaudry 1862, 1862-1867; Georgalis & Kear 2013; Garcia et al. 2016) at Nikiti [MN 11] and Pikermi, Turolian [MN 12-13]) and seemingly at the same time in Northern Africa (Djebel Semène, Late Vallesian, Tunisia) ( Gmira et al. 2013). This wide area indicates a much older diversification. Chersine is present with the double supracaudal (yet not dorsally and ventrally stabilised as in living specimens) in the Pliocene (Ruscinian, MN 15) of Perpignan (Ch. Pyrenaica (Depéret & Donnezan, 1890)), and of Poland. Chersine lineage is considered as dating back to the middle part of the Miocene at Langhian-Serravallian epochs, being considered as firstly represented by the species Paleotestudo canetotiana from Sansan (middle Miocene, early Astaracian, MN6) ( Broin 1977; Lapparent de Broin 2000, 2001). The lineage of Paleotestudo is here considered sensu Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c, being grounded on this oldest Paleotestudo species ( P. canetotiana ), which is not considered as a synonym of T. antiqua Bronn, 1831 sensu Corsini et al. 2014 and of T. catalaunica Bataller, 1926 sensu Pérez-García et al. 2016 (MN 7-8, late Astaracian). Notably, the contour of the anterior lobe and the shape of the epiplastral gular lip of these species are different, and whatever the individual considered variability. However, these species are all considered as part of the same larger lineage leading to Chersine ( Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c; Luján et al. 2016; Pérez-García 2017), being distinguished from the lineage of Agrionemys .

The first known representative of Agrionemys lineage seems to be Testudo bessarabica (Lapparent de Broin 2000, 2001; Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006a, b, c; Macarovici 1930; Riabinin 1918) from the late Miocene (Turolian, MN 12) of Taraklia and Ciobirciu ( Bessarabia, Moldavia). This species is the type species of Protestudo Č khkikvadze, 1970, for us a potential junior synonym of Agrionemys . It was recombined as Agrionemys bessarabica by Lapparent de Broin et al. (2006b). It has the same high shell due to a high bridge and wide and short xiphiplastron, in a posterior lobe with posteriorly well converging, straight or slightly convexe, lateral borders. The narrow anterior lobe has much converging borders and much protruded gulars. As Agrionemys , it has a long ventral gular overlap on the entoplastron, however longer with regard to Sherullah specimen AFG 130. Agrionemys bessarabica differs from living Agrionemys by the more posterior humeropectoral sulcus which is just posterior or clearly posterior to the entoplastron and not at all overlapping it: this is missing in Sherullah 9, but this is a character also known in some Chersine and Testudo specimens ( Gmira 1995; Gmira et al. 2013; Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006b) and that is then potentially specific rather than generic. Agrionemys bessarabica much differs by the gular lip which is anteriorly more narrowly protruding with converging lateral borders, as seen in the four ventrally figured specimens of Riabinin (1918: figs 3-4). This is different from Sherullah 9 AFG 130 specimen ( Fig. 3E View FIG ) which is devoid of gular protrusion as in some Agrionemys horsfieldii and A. kazachtanica living specimens. While, several other preserved living A. horsfieldii specimens from Khordkabul basin present more protruding gulars (REP coll.); they are then closer to A. bessarabica although the protrusion is less long, less anteriorly narrow and externally rounder. The entoplastron seems considerably larger than in Chersine and Testudo , at least it is longer in A. horsfieldii and in A. bessarabica known specimens. The entoplastron is visible in four of the five figured specimens of A. bessarabica ( Riabinin 1918: figs 3-4), appearing as more important in the anterior lobe, which is narrower on each side of this entoplastral bone (as in Sherullah 9 AFG 130), but anteriorly pointed: in Sherullah 9 AFG 130, the widely curved posteromedial border of the epiplastron (sutured with the entoplastron) in relation to its lateral width and the symmetrical juxtaposition Fig. 3F View FIG 1 View FIG , F 2 View FIG , seems also to indicate the presence of a wide entoplastron. Agrionemys bessarabica is different from both A. horsfieldii spp. and Sherullah 9 species by the deeper anal notch.

Agrionemys sp. (or previously cf. bessarabica ) is considered as present at Maragheh, Iran (late Miocene, early Turolian), by the specimen MNHN.F. MAR2424, MAR2425 (coll. Mecquenem-Morgan 1905-10) ( Lapparent de Broin et al. 2006c). In this country, as in Afghanistan, lives A. horsfieldii and not Chersine . The fossil is preserved by a part of posterior carapace of a male with the curved suprapygal-pygal area ( Fig. 3L View FIG ), and a fragment of hypoplastron; this specimen shows the inguinal notch bears a triangular medial inguinal scute which is well separated from the sulcus abdominofemoral, itself well separated from the hypoxiphiplastral suture ( Fig. 3M View FIG ). As Chersine , A. bessarabica and living Agrionemys , the Maragheh specimen differs from Testudo by the primitive absence of hypoxiphiplastral hinge, the suture being well separated from the abdominofemoral sulcus. It also conforms to A. bessarabica and living Agrionemys males by the obliquely much elevated, curved and protuding posterior border of the carapace ( Fig. 3L View FIG 2 View FIG ). This border was elevated above the plastral ventral level due to high bridge, at the difference with Chersine . Maragheh specimen is notably different from Chersine , as Sherullah 9 specimen and Agrionemys , by the absence of supracaudal division. Sherullah 9 and Maragheh male specimens share the long arched pygal with a long ventral supracaudal overlap ( Fig. 3B View FIG ), while the pygal is shorter for its length in observed living Agrionemys female specimens. In Sherullah 9 species, the epiplastral gular dorsal lip overhangs the dorsal epiplastral surface vertically ( Fig. 3D3 View FIG ) or nearly ( Fig. 3F3 View FIG , F 4 View FIG ) and it does not overlap the entoplastron, as in living Agrionemys and Ch. hermanni (which is a primitive character), and there is no gular pocket (also a primitive character): this feature is unknown in the not prepared A. bessarabica Riabinin’s specimens; it is not preserved in the Maragheh form.

In fine, as seen above, the size of the species from Sherullah 9 is similar to that of extant individuals of Agrionemys . It agrees by the conjunction of the following characters: neural 5 shape and length, male pygal shape and proportions with long ventral unique supracaudal overlap, dorsal epiplastral lip anterior to entoplastron and weak to absent gular pocket, suitable xiphiplastral shape and proportions, and short and straight anal notch. The species from Sherullah 9 is different from the living Agrionemys compared species and from A. bessarabica , a least by its ventrally shortest gular part on the entoplastron. However, it is morphologically closer to various Agrionemys extant specimens than to A. bessarabica by the character of wider and few projected gulars. It is similar to A. bessarabica and part of extant specimens by the xiphiplastral general morphology (those specimens with straighter lateral borders) and similar to A. bessarabica by the narrower anterior lobe on each side of the entoplastron. As living Agrionemys, Sherullah 9 species had a shorter anal notch than in A. bessarabica .

The presence of Agrionemys in Moldavia and Afghanistan is perhaps not its only fossil witness in Europe. The question is raised for Testudo brevitesta Vlachos & Tsoukala, 2015 , from the Pliocene of Milia ( Greece): beside the absence of indication of a hypoxiphiplastral hinge (the hypoplastron being broken anterior to the posterior lobe and not at a hinge), Vlachos & Tsoukala 2015 figure a wide shell in a “rounded at angles-rectangular” shape (as in some living Testudo and overall some Agrionemys specimens), a wide anterior lobe with rounded converging borders with narrow anteriorly rounded and few protruding gulars, an elevated anterior lobe extremity, an epiplastral dorsal gular lip anterior to the entoplastron which is very large. These characters are found in specimens of Agrionemys , particularly the large entoplastron, and they particularly agree with the shell of some MNHN.RA Agrionemys female specimens, those which are less short for their width than others. The more curved gular lip differs. The rounded posterior peripheral half collar presented as characteritisc of the species is of a female: it is similar to living compared female specimens of A. horsfieldii , although the Greek pygal is slightly more expanded medioposteriorly: this, really, can correspond to a specific difference. It is clearly different from the living Agrionemys species by the humeropectoral sulcus position which is primitively posterior to the entoplastron as in one of the four A. bessarabica ventrally figured specimen (being at its contact in the others). A larger entoplastron in the anterior lobe is also seen in other testudinines such as “ Ergilemys ” bruneti Broin, 1977 and Centrochelys sulcata ( Miller, 1779) (see figures in Broin 1977; Lapparent de Broin 2003). This is a homoplastic character, because observed in these different lineages but noting the width of the anterior lobe on each side of the entoplastron varies, according to each form. Nevertheless, no described Testudo species share together so many characters with Testudo brevitesta . It is interesting to notice here this possible European expansion of the genus Agrionemys before present times, tending to do a link with the more western living Agrionemys population (which is known in Georgia), but more material is necessary.

In Afghanistan, Sherullah 9 indetermined species is the first fossil representative of the Agrionemys lineage of the country and, also, the first described fossil turtle of the country. It belongs to the oldest representatives of the genus at late Miocene, early Turolian.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SuperFamily |

Ranoidea |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Agrionemys

| Lapparent, France de, Bailon, Salvador, Augé, Marc Louis & Rage, Jean-Claude 2020 |

T. catalaunica Bataller, 1926 sensu Pérez-García et al. 2016

| Perez-Garcia 2016 |

T. antiqua Bronn, 1831 sensu

| Corsini 2014 |

Paleotestudo

| Lapparent de Broin 2000 |

Paleotestudo

| Lapparent de Broin 2000 |

A. kazachstanica Čhkhikvadze, 1988

| Chkhikvadze 1988 |

Protestudo

| Chkhikvadze 1970 |

Agrionemys

| Khozatsky & Mlynarski 1966 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Chersine

| Merrem 1820 |

Testudo

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Testudo

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Testudo

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Testudo

| Linnaeus 1758 |