Brillanceausuchus babouriensis

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12400 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/F75787E0-FFBC-FFEE-05D2-0100827BB900 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Brillanceausuchus babouriensis |

| status |

|

BRILLANCEAUSUCHUS BABOURIENSIS

MICHARD ET AL., 1990

Type locality and horizon

Unnamed bed,?Barremian (Early Cretaceous), Babouri-Figuil Basin, north Cameroon.

Type specimen

UP BBR 201 , skull and partial skeleton .

Previous diagnoses and comments

Despite noting numerous similarities with atoposaurids, Michard et al. (1990) assigned Brillanceausuchus to its own family, Brillanceausuchidae , within Neosuchia . However, a monogeneric family has no systematic purpose, and Brillanceausuchidae has not been used by subsequent workers. Pending the recovery of closely related taxa that do not already form a named clade, we recommend disuse of Brillanceausuchidae . Brillanceausuchus has remained a neglected taxon in phylogenetic and comparative analyses, despite its apparent important morphology in possessing a number of ‘primitive’ character states (e.g. possession of a partially septated external nares and presence of a biserial osteoderm shield) alongside more ‘transitional’ morphologies between advanced neosuchians and eusuchians (e.g. reduced ventral exposure of the basisphenoid and procoelous presacral vertebrae) (Michard et al., 1990). It was regarded as an atoposaurid by Salisbury & Frey (2001) and Salisbury et al. (2006), and as an ‘advanced neosuchian’ by Turner (2015), without additional comment. To our knowledge, the only phylogenetic analysis to include Brillanceausuchus was conducted by Osi € et al. (2007: 174), who commented that its inclusion ‘gave much less resolution inside Eusuchia due to its incompleteness’ and did not report the results.

Discussion

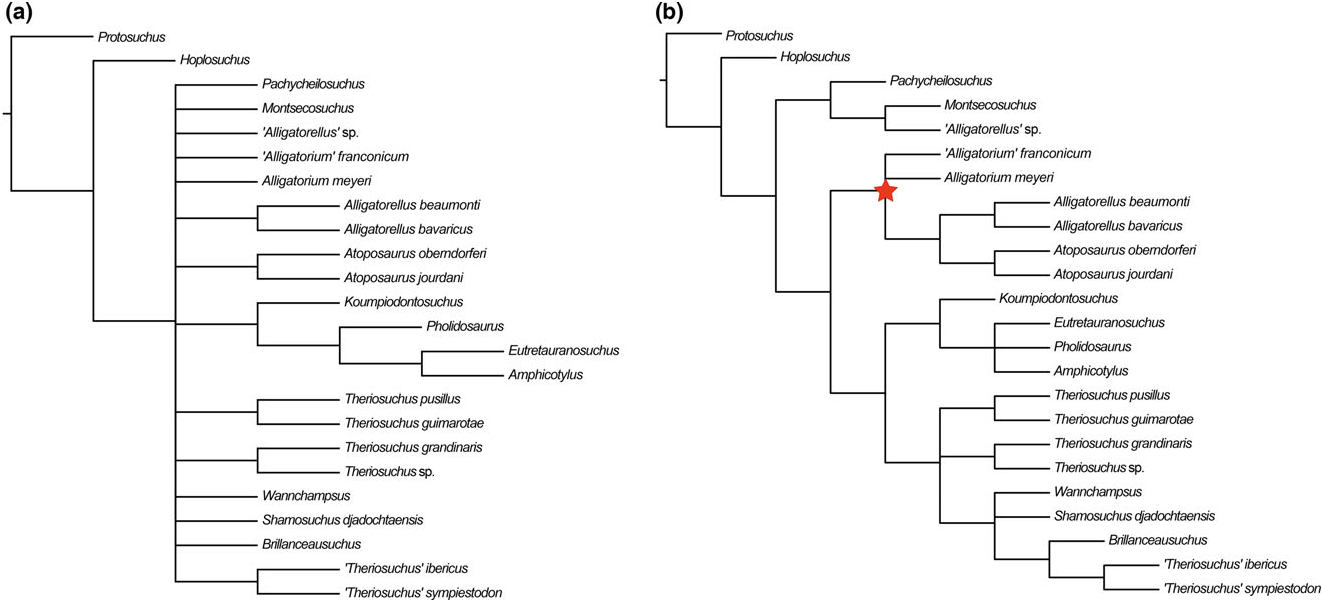

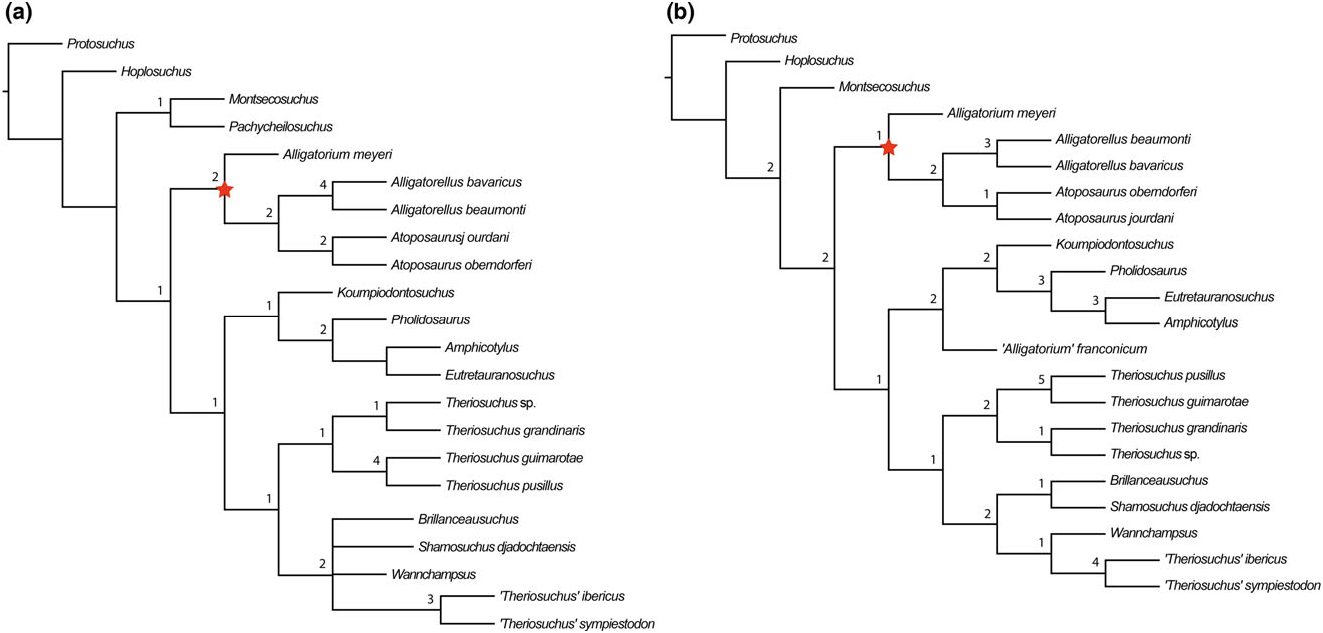

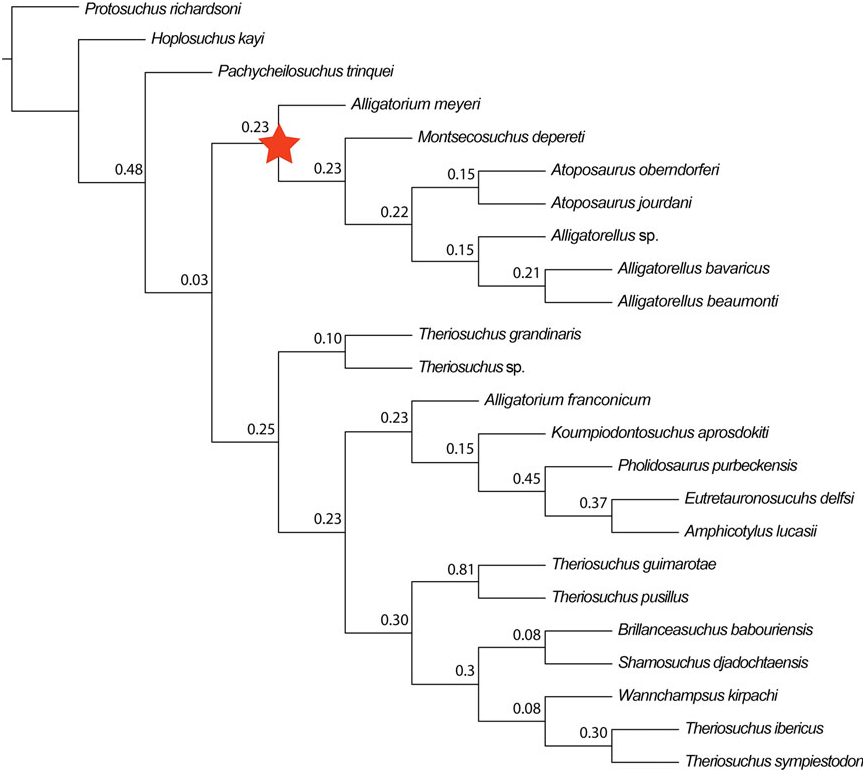

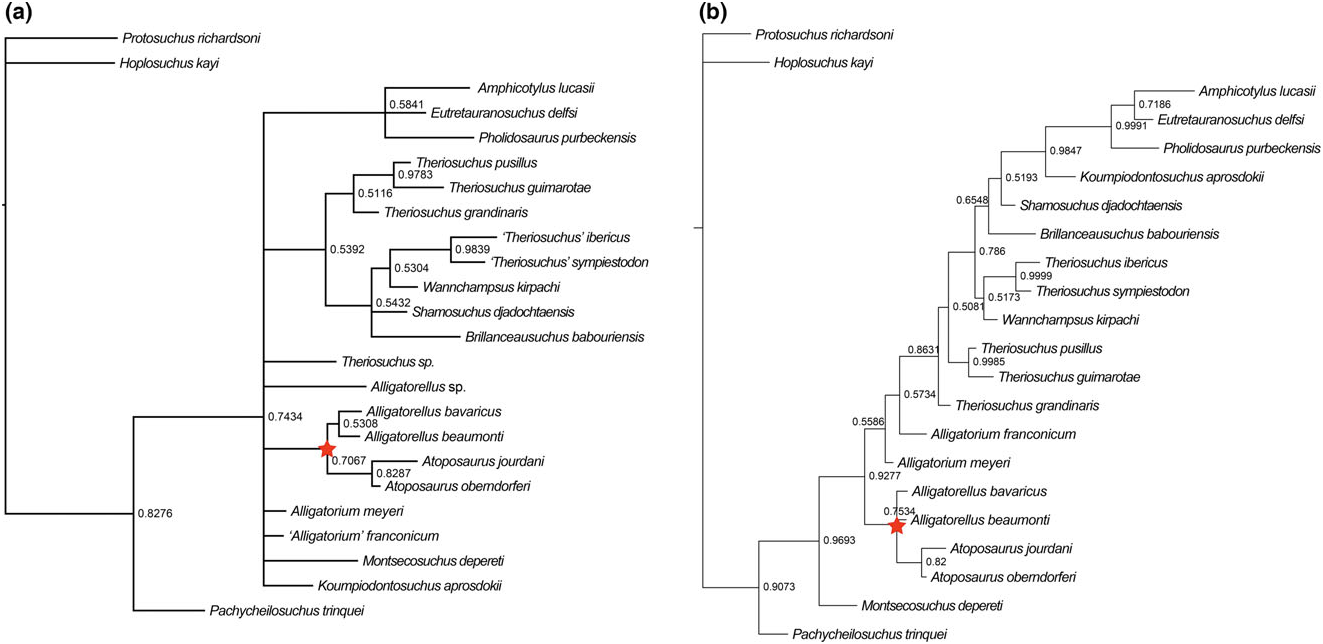

Brillanceausuchus possesses procoelous cervical and dorsal vertebrae (Michard et al., 1990), as well as fully pterygoidean choanae that are situated posteriorly to the posterior edge of the suborbital fenestrae, as in eusuchians (Buscalioni et al., 2001; Pol et al., 2009). Many authors have considered the presence of this combination of vertebral and palatal morphologies to imply that the eusuchian condition has evolved in parallel in several different neosuchian lineages, based on the underlying assumption that Brillanceausuchus is an atoposaurid, and therefore more basally positioned within Neosuchia (e.g. Brochu, 1999; Buscalioni et al., 2001; Salisbury et al., 2006). However, our preliminary results indicate that Brillanceausuchus belongs to Paralligatoridae ( Figs 4B View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 ), a clade most recently placed within Eusuchia (Turner, 2015). Therefore, the eusuchian condition might not be as homoplasious as previously regarded. Additional material assigned to Brillanceausuchus is currently being prepared, and comprises numerous skeletons (including skulls) preserved in three dimensions (J. Martin, pers. comm., 2015). We await the full description of this material before a comprehensive taxonomic assessment of Brillanceausuchus can be made, and preliminarily assign it to Paralligatoridae .

Preliminary emended diagnosis

(S1) proportionally long supratemporal fenestra, with anteroposterior length exceeding that of the orbit, and a skull length to supratemporal fenestra length ratio of <6.0 (5.36) (C29.0), and a skull width to supratemporal fenestra width ratio of 7.0 (C30.3); (S2) sinusoidal lateral nasal borders oblique to one another (C66.3), with abrupt widening adjacent to maxilla (C70.1); (S3) base of jugal postorbital process directed dorsally (C83.1); (S4) flat frontal dorsal surface (no longitudinal crest or periorbital rims) (C100.0); (S5) parietal – postorbital suture visible on the dorsal surface of the skull roof (C112.1) and within the supratemporal fenestra (C113.1); (S6) concavity at posterodorsal edge of squamosal – parietal contact (C117.1); (S7) lateral margins of squamosal and postorbital medially concave in dorsal view (C134.2), and dorsal surface of squamosal bevelled ventrally (C138.1), becoming unsculpted anteriorly (C148.1); (S8) squamosal posterolateral process elongate, distally tapered (C143.0) and depressed from skull table (C140.1); (S9) basisphenoid ventral surface mediolaterally narrower than basioccipital (C191.0), and basioccipital with large, well-developed bilateral tuberosities (C192.1); (S10) ventrolateral surface of anterior portion of dentary strongly mediolaterally compressed and flat (C215.0), with grooved ornamentation on external surface (C227.1); (S11) retroarticular process projects posteriorly and dorsally recurved (C242.3); (S12) posterior dentary teeth occlude medial to opposing maxillary teeth (C263.0); (S13) rounded and ovate dorsal osteoderm shape (C308.0).

PACHYCHEILOSUCHUS TRINQUEI , ROGERS 2003

Pachycheilosuchus trinquei is known from a nearcomplete, disarticulated skeleton and partial skull from the Albian (Early Cretaceous) Glen Rose Formation of Erath County, Texas, USA. Initially described as a possible atoposaurid (Rogers, 2003), a position at the base of Atoposauridae was subsequently demonstrated in the analyses of Turner & Buckley (2008) and Pol et al. (2009). However, more recent analyses have placed Pachycheilosuchus outside of Atoposauridae , either within the basal eusuchian clade Hylaeochampsidae [Buscalioni et al., 2011 (although note that this study used Theriosuchus as an outgroup, and included no definite atoposaurids); Turner & Pritchard, 2015], or just outside the eusuchian radiation (Adams, 2013; Narvaez et al., 2015). Rogers (2003) based his assignment to Atoposauridae primarily on the presence of a jugal with equally broad anterior and posterior processes, and the possession of procoelous presacral vertebrae. However, this jugal morphology is known in other neosuchians, including Paluxy- suchus, as well as thalattosuchians (Adams, 2013). The presence of procoelous vertebrae could be more broadly distributed amongst non-neosuchian eusuchians than previously recognized, and full procoely is not definitively known amongst any atoposaurid species (see also Salisbury & Frey, 2001). Hylaeochampsid affinities are supported by the reinterpretation of a defining character state for Atoposauridae , pertaining to whether the bar between the orbit and supratemporal fenestra is narrow, with sculpting restricted to the anterior surface (Clark, 1994). Buscalioni et al. (2011) regarded this feature to be associated more broadly with ‘dwarfism’ (as initially proposed for Pachycheilosuchus ) or immature specimens, and not a synapomorphy of Atoposauridae . Pachycheilosuchus is additionally unusual in the retention of an antorbital fenestra, to which the maxilla contributes (Rogers, 2003), which is similar to T. guimarotae (Schwarz & Salisbury, 2005) and Alligatorellus bavaricus (Tennant & Mannion, 2014) .

The present study was not designed to resolve the phylogenetic placement of Pachycheilosuchus , except whether or not to include it within Atoposauridae . We support its exclusion from Atoposauridae , but cannot provide further comment on its placement within Hylaeochampsidae (Buscalioni et al., 2011) . It is unusual in that we recover Pachycheilosuchus in a more stemward position than Atoposauridae . We anticipate that inclusion of a broader range of atoposaurid specimens, Theriosuchus species , hylaeochampsids (including Pietraroiasuchus ormezzanoi ; Buscalioni et al., 2011), and additional paralligatorids within a larger Neosuchia-focussed data matrix, will help to resolve the position of Pachycheilosuchus and its clearly important role in the ascent of advanced neosuchians and Eusuchia.

WANNCHAMPSUS KIRPACHI ADAMS, 2014

The ‘Glen Rose Form’ has been commonly referred to in neosuchian systematics since it was first briefly mentioned and figured by Langston (1974). Comprising a skull and lower jaw from the Early Cretaceous (late Aptian) Antlers Formation of Montague County, Texas, USA, it was described as resembling the extant dwarfed crocodile Osteolaemus tetraspis , and Langston (1974) also noted similarities to T. pusillus . Subsequently, Adams (2014) erected Wannchampsus kirpachi for two skulls and postcranial material from the late Aptian (Early Cretaceous) Twin Mountains Formation of Comanche County ( Texas, USA), and assigned the ‘Glen Rose Form’ to this taxon. Adams (2014) noted that the skull of Wannchampsus was similar to that of T. pusillus , sharing features such as medial supraorbital rims, and therefore prompting its inclusion in the present analysis and discussion here. However, Wannchampsus is distinct from T. pusillus in: (1) the possession of an enlarged third maxillary tooth (instead present at the fourth position in T. pusillus ); (2) the absence of an antorbital fenestra; (3) choanae with an anterior margin close to the posterior edge of the suborbital fenestra (whereas it is more anteriorly placed in T. pusillus ); and (4) the definitive presence of procoelous dorsal and caudal vertebrae. We recovered Wannchampsus in a position close to Shamosuchus [Pol et al., 2009; see also Adams (2014) and Turner (2015)], forming a paralligatorid clade with Sabresuchus and Brillanceausuchus .

KARATAUSUCHUS SHAROVI EFIMOV, 1976

Karatausuchus sharovi is known only from a single skeleton of a juvenile individual from the Late Jurassic (Oxfordian – Kimmeridgian) Karabastau Formation in southern Kazakhstan. It was considered to be an atoposaurid by Efimov (1976, 1988), but more closely related to paralligatorids by Efimov (1996). Storrs & Efimov (2000) argued that it was a relatively basal crocodyliform owing to the possession of amphiplatyan vertebral centra, and designated it as a questionable atoposaurid. It is generally similar to atoposaurids in being small, at only 160 mm in total anteroposterior body length, but possesses reduced dermal osteoderms, suggestive of a juvenile phase of growth. Intriguingly, Storrs & Efimov (2000) observed over 90 small, labiolingually compressed teeth within the jaws, a feature unique amongst crocodyliforms. It also possesses 46 caudal vertebrae, approaching the condition known for Atoposaurus . However, it has eight cervical vertebrae, placing it intermediate to Protosuchus (nine cervical vertebrae) and the majority of other atoposaurids (seven cervical vertebrae, with the exception of Atoposaurus jourdani , which appears to have six). Karatausuchus is similar to atoposaurids in that its skull length to orbit length ratio is relatively low, between 3.0 and 4.0 (3.37), but the other diagnostic features presented in this study for Atoposauridae cannot be assessed in the single known specimen. Therefore, we agree with Buscalioni & Sanz (1988) that Karatausuchus sharovi is currently too poorly known to be assigned to any family, including Atoposauridae , and regard it as an indeterminate crocodyliform. However, we still tentatively regard it as a valid taxon, owing to the high number of cervical and caudal vertebrae, and the possession of an anomalously high number of teeth.

HOPLOSUCHUS KAYI GILMORE, 1926

Gilmore (1926) originally recognized this taxon, based on a near-complete and articulated skeleton from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation at Dino- saur National Monument ( Utah, USA), as a pseudosuchian archosaur. Subsequently, several authors assigned Hoplosuchus kayi to Atoposauridae (Romer, 1956; Kuhn, 1960; Steel, 1973), based on its overall size, and the possession of relatively large, posteriorly placed, and anterolaterally facing orbits. However, Buffetaut (1982) and Osmolska et al. (1997) regarded Hoplosuchus as more similar to protosuchians, but noted that its phylogenetic affinities remained uncertain. In their phylogenetic assessment of Atoposauridae, Buscalioni & Sanz (1988) concluded that Hoplosuchus is a ‘protosuchian-grade’ crocodyliform.

Our examination of this taxon could not confirm any definitive atoposaurid affinities. Hoplosuchus retains features present in basal crocodyliforms, including a small and circular antorbital fenestra, and a triangular lateral temporal fenestra that is nearly as large as the orbit. Potential autapomorphies for Hoplosuchus include: (1) a steeply posteriorly inclined quadrate; (2) the pterygoid bearing a descending process that is extensively conjoined in the mid-line anterior to the basisphenoid; and (3) a lower jaw lacking the external mandibular fenestra (Steel, 1973). Hoplosuchus has slender limbs, the dorsal armour is composed of paired oblong plates, and the caudal region is completely enclosed by dermal ossifications. A full revision of protosuchian crocodyliforms is currently underway (A. Buscalioni, pers. comm., 2014), and we await this before drawing any conclusions about the affinities of Hoplosuchus . Nonetheless, we exclude Hoplosuchus from Atoposauridae .

SHANTUNGOSUCHUS CHUHSIENENSIS YOUNG, 1961

Young (1961) initially identified this taxon, based on a near-complete skeleton and skull from the Early Cretaceous Mengyin Formation of Shandong Province, China, as an atoposaurid. This referral was subsequently supported by Steel (1973), who provided an emended diagnosis in his discussion of Atoposauridae . This included: (1) a triangular-shaped skull; (2) closely set teeth deeply implanted in independent alveoli; (3) seven cervical and 18 dorsal vertebrae; (4) short cervical vertebral centra; (5) relatively long dorsal vertebral centra; (6) a slightly shorter ulna than humerus; (7) the tibia significantly exceeding the femur in length; and (8) the forelimbs being proportionally long. However, Buffetaut (1981) and Buscalioni & Sanz (1988) both excluded Shantungosuchus from Atoposauridae . Wu et al. (1994) regarded much of the original interpretation of Young (1961) as incorrect, and revised Shantungosuchus , finding it to be more closely related to protosuchians than to atoposaurids. We concur with these authors and exclude Shantungosuchus chuhsienensis from Atoposauridae , supporting a basal position within Crocodyliformes . However, we note that atoposaurids do share numerous metric features with protosuchians, reflecting their small body size and paedomorphic retention of basal morphologies.

INDETERMINATE REMAINS PREVIOUSLY ATTRIBUTED TO ATOPOSAURIDAE

Alongside these named taxa, numerous additional

remains (primarily teeth) have been referred to Ato-

posauridae. These referrals have generally been

based on the dental morphotypes that have been

regarded as characteristic of Theriosuchus and, in

stratigraphical order, comprise:

1. Teeth comparable to those of Theriosuchus were described from two localities from the early Bathonian of southern France (Kriwet et al., 1997). Their referral to Atoposauridae was based on the presence of different morphotypes, and the teeth were thought to represent two distinct species. The first of these ‘species’ includes several dozen teeth (Larnagol, IPFUB Lar-Cr 1- 20, and Gardies, IPFUB Gar-Cr 1-20). Amongst this set of teeth, Kriwet et al. (1997) identified four gradational morphotypes, based on their inferred positions in the dental arcade. However, their referral to Atoposauridae is based mainly upon them being heterodont, a feature that is not exclusive to either Atoposauridae or Theriosuchus . The second ‘species’ (Larnagol, IPFUB Lar-Cr 21-40) differs in possessing more prominent ridges on the crown surfaces (Kriwet et al., 1997). These were referred to Atoposauridae by Kriwet et al. (1997) based on their inferred heterodonty; however, it cannot be determined whether or not all of these morphotypes belong to the same heterodont taxon, or two or more homodont or heterodont taxa. As atoposaurids are now considered to have a homodont (pseudocaniniform) dental morphology, these teeth cannot be referred to this group. They probably represent at least one (and probably more) small-bodied heterodont taxon, and therefore we consider them to be only referable to Mesoeucrocodylia indet. at present.

2. Small crocodyliform teeth were noted from the Bathonian ‘stipite’ layers of the Grand Causses ( France) by Knoll et al. (2013) and Knoll & Lopez-Anto nanzas ~ (2014), and referred to an indeterminate atoposaurid. No further details were given, and therefore we regard these as representing indeterminate crocodyliforms pending further description of this material.

3. 1391 specimens comprising teeth, osteoderms, and a jaw fragment with teeth, as well as undescribed cranial and postcranial specimens, from the Bathonian of Madagascar were referred to Atoposauridae (Flynn et al., 2006) . Based on the description and figures provided, these teeth appear to be pseudocaniniform in morphology, with well-developed mesial and distal carinae and a ridged enamel surface. Although they vary in shape and size (up to 10 mm in apicobasal length), none can be defined as pseudoziphodont, ziphodont, lanceolate, labiolingually compressed, or low-crowned. Based on the brief description, we cannot conclude that these teeth belonged to an atoposaurid, and therefore regard them as Mesoeucrocodylia indet., pending further description. Further examination of this material, along with remains identified as Theriosuchus sp. by Haddoumi et al., [2016 (see above)], will be important in examining evidence for the presence of atoposaurids and Theriosuchus in the Middle Jurassic of Gondwana.

4. Thies & Broschinksi (2001) described teeth from the Kimmeridgian of northern Germany as ‘ Theriosuchus -like’, but identified them as belonging to a small-bodied mesosuchian. Karl et al. (2006) provisionally referred these teeth to Mesoeucrocodylia indet., stating that their morphology is not known for any other crocodylomorph. We follow this decision of Karl et al. (2006), pending the direct comparison of this material with Theriosuchus and other small-bodied crocodyliforms.

5. A fragmentary set of specimens (IVPP V10613 View Materials ) from the Early Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, including cranial and mandibular elements, were assigned to cf. Theriosuchus sp. (Wu et al., 1996). However, the material might not be referable to a single individual or even taxon, as it was collected from across an extensive outcrop. The figured osteoderm (Wu et al., 1996) is almost identical in overall morphology to Alligatorellus sp. (MB.R.3632; Schwarz-Wings et al., 2011), including the position and extent of the lateral keel, and the near-absence of the anterior process of the ilium is similar to that of Montsecosuchus . The dorsal vertebrae possess the ‘semi-procoelous’ condition, similar to Pachycheilosuchus . The cranioquadrate canal is closed, and therefore IVPP V10613 View Materials can be excluded from Atoposauridae . The external mandibular fenestra is absent, similar to paralligatorids and T. pusillus . Additionally, the parietals bear a longitudinal median ridge on the dorsal surface, which Wu et al. (1996) used to link IVPP V10613 View Materials with Theriosuchus , although this feature is herein shown to be more widespread throughout Neosuchia . Wu et al. (1996) assigned IVPP V10613 View Materials to Therio- suchus based on the broad intertemporal region, raised supratemporal rims, and elevated medial orbital margin, but these features are found in numerous other taxa. Based on this combination of unusual characteristics, we think it likely that IVPP V10613 View Materials comprises more than one taxon, including at least one non-atoposaurid, non- Theriosuchus taxon, and one Theriosuchus -like taxon. We therefore regard IVPP V10613 View Materials as representing Neosuchia indet. pending further study of this material.

6. A skull fragment (NHMUK PV OR176) was assigned to Theriosuchus sp. from the Berriasian – Barremian of the Isle of Wight, UK ( Buffetaut, 1983; Salisbury & Naish, 2011). Buffetaut (1983) assigned the posterior portion of a skull to Theriosuchus sp. based on comparison with the lectotype specimen of T. pusillus (NHMUK PV OR48216). It has a median longitudinal ridge on the parietal, similar to all specimens assigned to Theriosuchus , but also to Alligatorium meyeri and paralligatorids. The otoccipitals also meet dorsal to the foramen magnum, separating it from the supraoccipitals, a feature shared with T. pusillus , T. guimarotae , and paralligatorids. The contact between the parietal and the squamosal on the dorsal surface, posterior to the external supratemporal fenestra, is also weakly developed, not forming the deep groove that characterizes T. pusillus . Therefore, we cannot determine whether this specimen represents Theriosuchus or another advanced neosuchian, and thus we consider this specimen to represent Neosuchia indet., pending its comparison to a broader set of neosuchians. In addition, Buffetaut (1983) assigned some procoelous vertebrae (the type of ‘ Heterosuchus valdensis ’) from the Early Cretaceous of the UK to Theriosuchus . The presence of procoely indicates that it is not referable to Theriosuchus (see below), and it is instead regarded as an indeterminate neosuchian.

7. Indeterminate remains (primarily teeth) attributed to atoposaurids, usually referred to Theriosuchus based on heterodont tooth morphotypes, have been identified from numerous sites in the Aptian – Albian (late Early Cretaceous) of North America (e.g. Pomes, 1990; Winkler et al., 1990; Cifelli et al., 1999; Eaton et al., 1999; Fiorillo, 1999; Garrison et al., 2007; Oreska, Carrano & Dzikiewicz, 2013). However, because of our removal of Theriosuchus from Atoposauridae , it is more likely that these ‘atoposaurid’ remains represent other small-bodied taxa. We tentatively consider these remains to represent Mesoeucrocodylia indet., pending further study.

8. Theriosuchus -like teeth (MTM V 2010.243.1) were described from the Santonian of western Hungary (Iharkut), but conservatively referred to Mesoeucrocodylia indet (Osi € et al., 2012). These teeth are lanceolate in crown morphology, and possess pseudoziphodont carinae. Martin et al. (2014a) briefly mentioned the presence of two additional undescribed maxillae from the same locality, which together with the teeth might be referable to Theriosuchus . As we have recombined the Maastrichtian occurrences of ‘ Theriosuchus ’ into a new taxon, Sa. sympiestodon , it is best that these teeth be regarded as Neosuchia indet., pending further analysis of this material and the possibly associated maxillae.

9. A Theriosuchus -like tooth was described from the Campanian – Maastrichtian of Portugal by Galton (1996). This tooth is distinct from Theriosuchus , possessing a fully ziphodont morphology, and was suggested to instead belong to Bernissartia ( Lauprasert et al., 2011) . However, here we consider it to belong to an indeterminate neosuchian based on the more widespread distribution of ziphodont dentition.

10. The stratigraphically youngest material assigned to Atoposauridae comes from the middle Eocene Kaninah Formation of Yemen (Stevens et al., 2013). This fragmentary material was tentatively designated as an atoposaurid, based on the presence of a ziphodont tooth crown, a procoelous caudal vertebral centrum, a biserial osteoderm shield (although see below), and polygonal gastral osteoderms. However, none of these characteristics is unambiguously diagnostic under our revised definition of Atoposauridae , and this material probably comprises a small, advanced eusuchian, based on the presence of procoelous caudal vertebrae. The presence of a biserial osteoderm shield is usually considered diagnostic for Atoposauridae ; however, our analyses demonstrate that this feature is more widespread amongst smallbodied neosuchians. Furthermore, the material from Yemen is too fragmentary to confidently infer that the osteoderm shield was biserial. Therefore, we regard this material as an indeterminate eusuchian pending the discovery of more complete and better preserved specimens.

| UP |

University of Papua and New Guinea |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.