Himasthla rhigedana Dietz, 1909

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4711.3.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:85D81C2D-0B66-4C0D-B708-AAF1DAD6018B |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EF6AD377-8945-8B24-FF39-FA0DFCE5FB95 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Himasthla rhigedana Dietz |

| status |

|

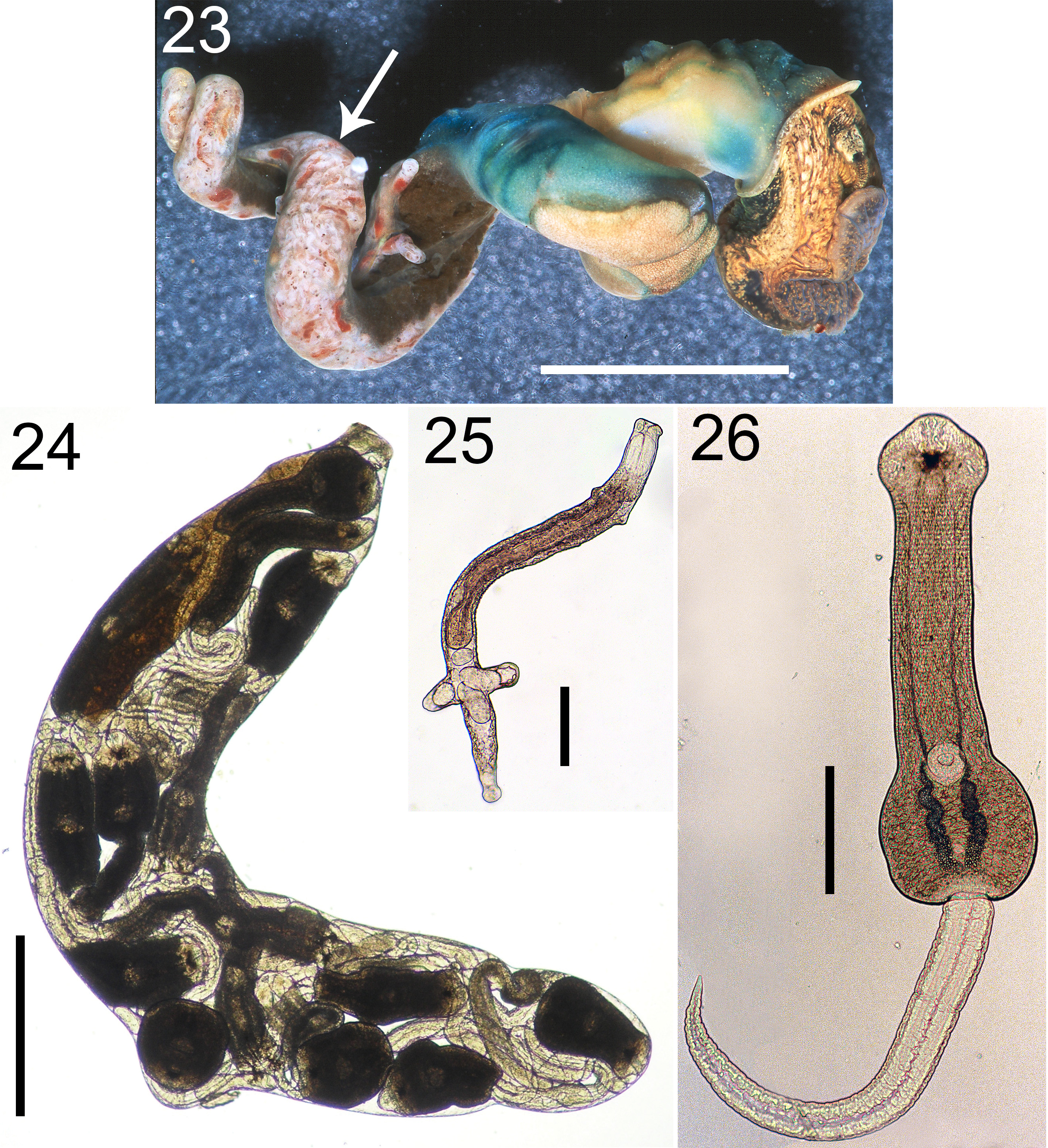

(6. Hirh; Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 23–26 View FIGURES 23–26 )

Diagnosis: Parthenitae. Colony comprised of active rediae, densely concentrated in snail gonad region. Rediae translucent white to colorless, often with prominent pigmented gut; when filled with cercariae, rediae appear opaque white with scattered black pigment (actually, the cercariae’s anterior pigment); ~ 1300–1700 µm long, oblong to elongate (length:width up to ~6:1), with posterior appendages that are often not pronounced.

Cercaria . Body opaque white with black pigment between and around eyespots; oculate; with oral and ventral sucker; with main excretory ducts forming a tall “v” in which the anteriorly extending branches greatly narrow anterior to ventral sucker; body ~ 600 µm long, ~equal in length to tail; tail simple.

Cercaria behavior: Fresh, emerged cercariae remain in water column, swim ~continuously, lashing tail back and forth, forming a figure 8, and will often encyst on dissection dish or in pipette during transfer.

Similar species: Hirh is readily separated from all the other echinostomatoids by having pigmented eyespots. It is easily separated from the notocotylid Cajo [4] by having a ventral sucker, a spined collar, and the redia colony being localized in the visceral mass.

Remarks: Adams and Martin (1963) demonstrated the life cycle. They described miracidia, rediae, cercariae, metacercariae from experimentally infected horn snails, and adults from experimentally infected young domestic chickens. Adams and Martin (1963) identified the adults as Himasthla rhigedana , which was originally described from naturally occurring adults from birds in Tunisia. This suggests that H. rhigedana represents a globally distributed cryptic species complex.

Deblock (1966) felt that the collar spine pattern of this species, as illustrated in Adams and Martin (1963), differed from the pattern characterizing H. rhigedana (based on Dietz’s original description and on Deblock’s observations). Deblock therefore proposed a new name for this species, H. californiensis . This nomenclatural act is not widely known, and the species in C. californica has typically been referred to as H. rhigedana . Further, I do not adopt Deblock’s proposed name, as the supposed difference is based on an illustration in Adams and Martin (1963), and that illustration does not adequately depict the spine pattern as we have observed it or as it is figured in Maxon and Pequegnat (1949). The discrepancy with Maxon and Pequegnat (1949) is particularly important, as Adams and Martin (1963) wrote that they and Maxon and Pequegnat (1949) dealt with the same species. Careful morphological and molecular work would resolve this issue, including whether cryptic species explain some of the discrepancies.

This species corresponds to “ Himasthla sp.” of Hunter (1942), “Echinostome I of Maxon and Pequegnat (1949), and the “large pigmented echinostome” of Martin (1955).

Mature, ripe colonies comprise ~23% the soft-tissue weight of an infected snail (summer-time estimate derived from information in [ Hechinger et al. 2009]).

Hirh infection causes (stolen) snail bodies to grow ~ 2x faster than uninfected snails ( Hechinger 2010).

This species has a caste of soldier rediae (noted in Hechinger et al. (2011b) and carefully documented in Garcia- Vedrenne et al. [2016]).

Nadakal (1960a;b) presents information on the pigments of the rediae and cercariae of this species.

As part of one of the first studies documenting the syncytial nature of trematode integuments, Bils and Martin (1966) examined the fine structure and development of the tegument for the rediae and cercariae of this species.

Dimitrov et al. (2001) characterize the distribution of cercaria tegumental papillae for this species.

Oates and Fingerut (2011) used histology to carefully document what is readily observed in fresh dissections: that Hirh cercaria, like most or all of the trematodes in the guild, make their way to, and accumulate in, the host snail’s perirectal sinus before exiting the host. The authors used videography to document that the cercariae exit snail tissues from an area near the snail’s anus.

Fingerut et al. (2003a) and Zimmer et al. (2009) examined several behavioral and environmental aspects of cercaria emergence and dispersal ecology for this species.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |