Ctenodactylus vali, Thomas, 1902

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6587796 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6587814 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/8D7887B8-442E-FFE1-B28C-F9FABF196761 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Ctenodactylus vali |

| status |

|

5. View Plate 16: Ctenodactylidae

Desert Gundi

Ctenodactylus vali View in CoL

French: Goundi du désert / German: Wiistengundi / Spanish: Gundi del desierto

Other common names: Sahara Gundi, Thomas's Gundi

Taxonomy. Cienodactylus vali Thomas, 1902 View in CoL ,

“Wadi Bey,just northwest of Bonjem” (= ¢.330 km south-east of Tripoli, Libya).

This species is monotypic.

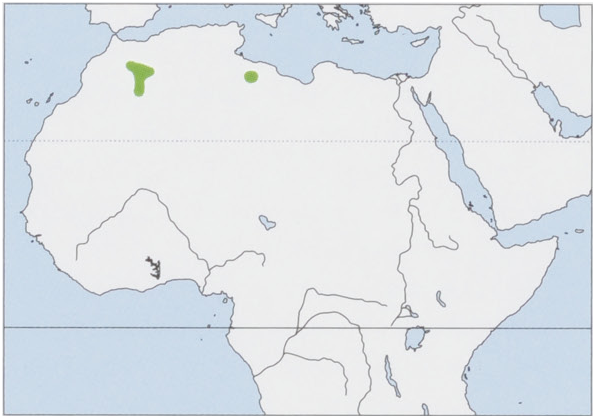

Distribution. N Africa in two discrete and widely separated areas (NE Morocco & NW Algeria and NW Libya). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 124-185 mm, tail 27-43 mm; weight up to 185 g. The Desert Gundi is, on average, smaller than but similar in external morphology and color to the Common Gundi ( C. gundi ). Despite their similarity, there are some morphological, behavioral, and communicative differences between them. The Desert Gundi has more inflated auditory bullae and proportionally longer large intestine than the Common Gundi. Fecal pellets of the Desert Gundi are shorter than those of the Common Gundi. Calls of the Desert Gundi are of higher frequency than those of the Common Gundi.

Habitat. Rocky deserts including mountain slopes, edges of “hamadas” (stony desert plains), “wadis” (ephemeral riverbeds), “rift” (linear down-faulted depressions), and small mountains. The Desert Gundi can be found in semi-desert areas.

Food and Feeding. The Desert Gundiis herbivorous. It lives in areas with plant cover of ¢.2%, exceptfor a few weeks every few years following rain. The Desert Gundieats, in order of preference, the crucifer Eremophyton chevallieri ( Brassicaceae ) and the composite Amberboa leucantha ( Asteraceae ), followed by grass genera Cymbopogon and Aristida (both Poaceae ). Plants included in its diet have lower water content than those eaten by the Common Gundi . The Desert Gundi mainly forages at dawn and dusk when temperatures are less extreme.

Breeding. Desert Gundis start breeding at 7-9 months old, and females have a vaginal closure membrane during periods of sexual inactivity. Unlike the Common Gundi, the Desert Gundiis sexually inactive most of the time, and its gestation is 60-65 days. Desert Gundis produce two litters each year under favorable conditions with up to three newborns in them (two on average), but they do not reproduce in extreme conditions and scarcity of food. Firstlitters are usually born in February-March and the second in April-May (these dates are delayed by c.2 months for individuals that live in high elevations). A prepartum estrus is suspected for the second copulation. Females are able to store spermatozoa in their genital tracts for at least two months and use them without further copulation to produce a replacement litter. Social behavior of the Desert Gundi greatly differs from that of the Common Gundi. A Desert Gundi lives alone most of the year. At the end of autumn, a female settles in a place, and several males try to join her. After a familiarization period, only one male is selected, and supernumerary males disappear. The male stays with the female during gestation, but he leaves before birth of the first litter. Neonates are precocial and born fully furred with their eyes and ears open and functional. Young remain close to their shelter, but sharing a night shelter between mother and youth is short-lived and stops well before weaning. The mother joins the young in the morning and may spend the rest of the afternoon with them. Young Desert Gundis from the first litter disperse before birth of the second litter in April-May. At the end ofJune, all individuals become erratic, and it is not until November after establishment of male-female relationships that these individuals become sedentary again.

Activity patterns. Desert Gundis sunbathe, forage, rest in the shade, and groom. The Desert Gundi spends more time (50-70%) outside than the Common Gundi (50%), but during the hot season, these percentages decrease, never exceeding 15%; in June, the Desert Gundi might be inside its shelter from 11:00 h to 17:00 h, longer than for the Common Gundi . The Desert Gundi replaces sunbathing by resting in the shade at lower temperatures than the Common Gundi , perhaps because of lower water content in plants that the Desert Gundi consumes compared with those eaten by the Common Gundi . Desert Gundis emit panic calls if a predator suddenly appears or alert calls if it is seen from a safe distance.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Desert Gundi is usually sparsely distributed, but high density may be observed under favorable conditions (up to 18 ind/ha). It is essentially solitary from June to late October. Home ranges are usually smaller (100-500 m* in the wet season and 1125 m® in the hot season) than those of the Common Gundi . Unlike Common Gundis, Desert Gundis do not establish strong or lasting social bonds.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Data Deficient on The [UCN Red List. The Desert Gundi does not seem to be threatened, and decreases in densities are probably due to climatic changes.

Bibliography. Aulagnier (2008d), Dieterlen (2005b), George (1974, 1978, 1981a, 1982, 2001), Gouat, J. (1985, 1986, 1989), Gouat, J. & Gouat (1984, 1987), Gouat, J. et al. (1985), Gouat, P (1991, 1992, 1993, 2013), Gouat, P & Gouat (1983, 1987), Lopez-Antonanzas & Knoll (2011), Pocock (1922), Ranck (1968), de Rouffignac et al. (1981).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Hystricomorpha |

|

InfraOrder |

Ctenodactylomorphi |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Ctenodactylus vali

| Don E. Wilson, Thomas E. Lacher, Jr & Russell A. Mittermeier 2016 |

Cienodactylus vali

| Thomas 1902 |