Teruelictis riparius

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12063 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/735BA43E-4A3F-3F3B-FE81-FD82340FC015 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Teruelictis riparius |

| status |

|

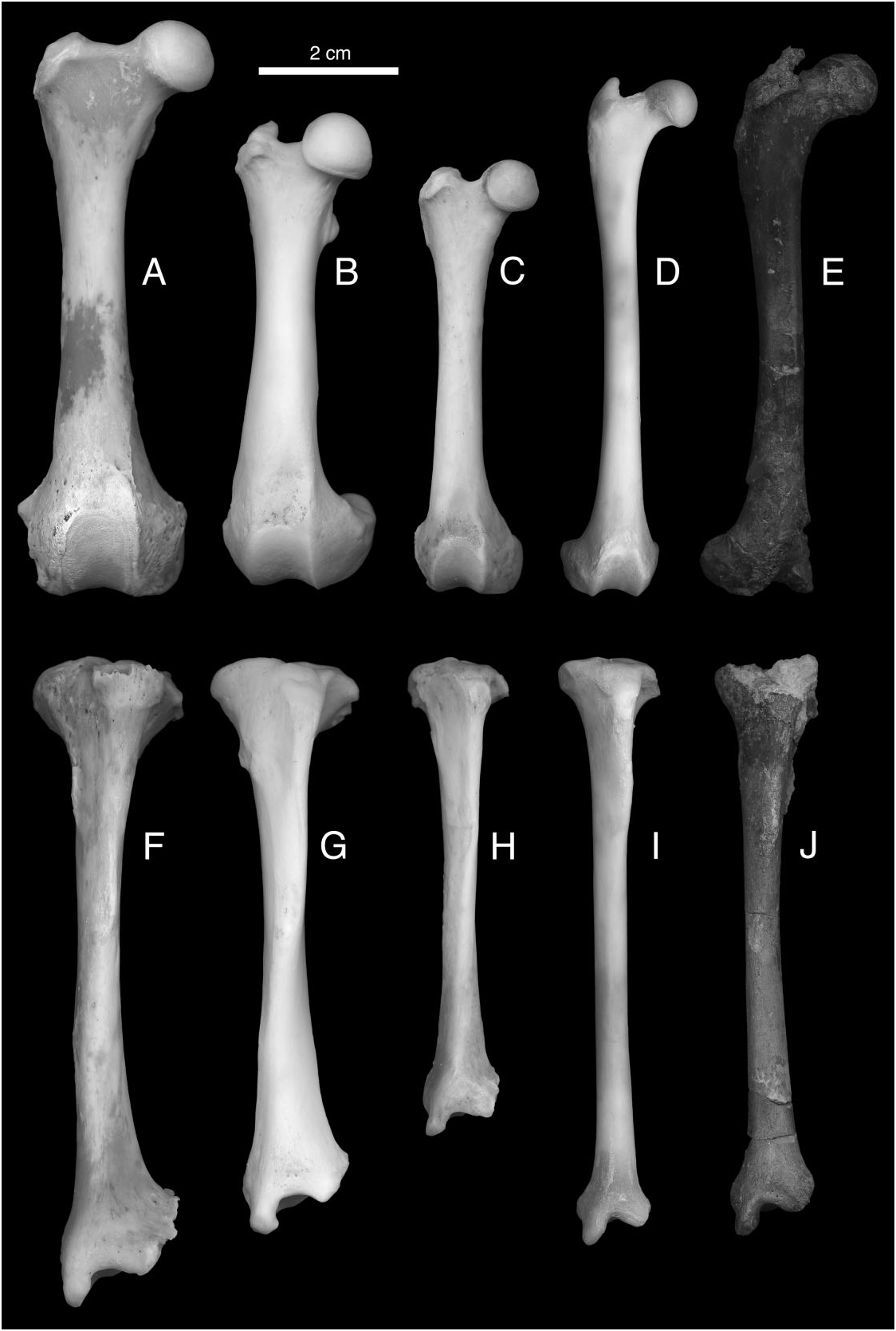

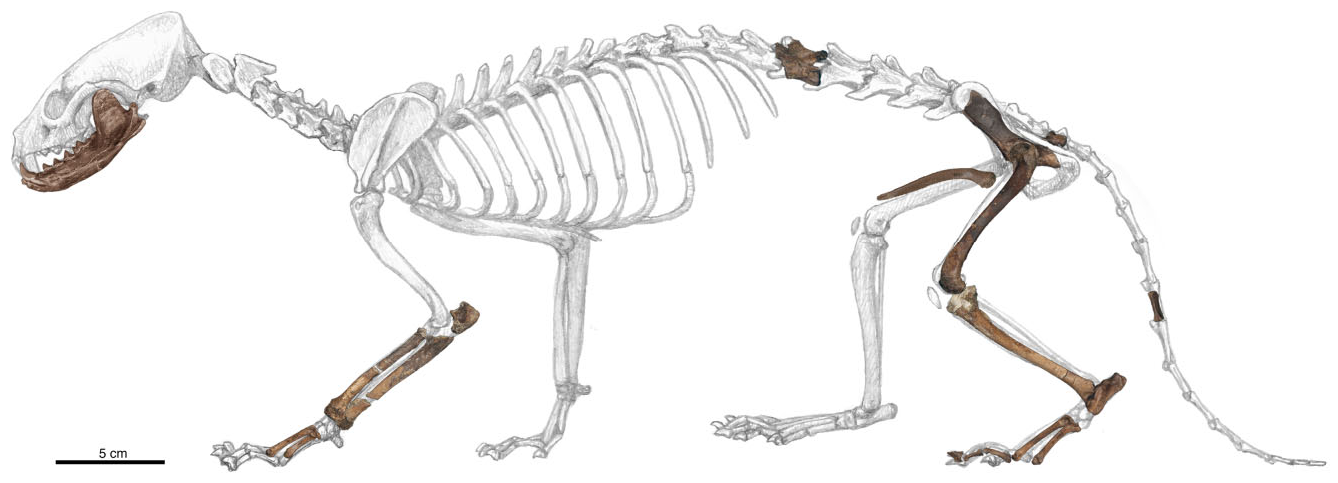

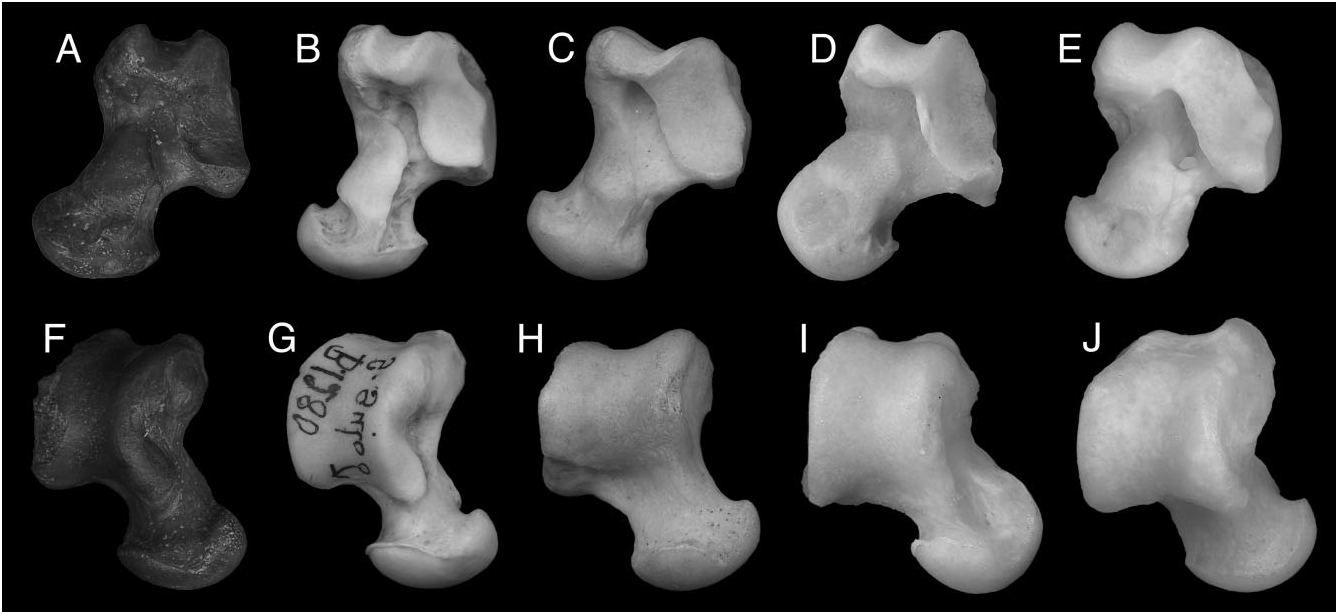

The new taxon Te. riparius from La Roma 2 provides invaluable data about the postcranial anatomy of primitive otters, which was previously known by a small number of fragmentary fossils of Par. jaegeri ( Helbing, 1936; Viret, 1951). Nevertheless, from our study, it is clear that the Vallesian Te. riparius had a much more gracile postcranial skeleton than that of its Middle Miocene relative Par. jaegeri and extant otters, thus representing a separate lineage from that leading to robust and aquatic otters ( Fig. 14 View Figure 14 ). This is very interesting as the dental morphology of Te. riparius is not so different from the primitive pattern seen in early otters. The most remarkable differences are found in the lumbar region and in the proportions of the long bones ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ); these latter bones are clearly more slender than those of most of the compared species, including Par. jaegeri , and similar to those of the martens and, to a lesser degree, to the Asian small-clawed otter A. cinereus , interestingly, the least aquatic of all the otters ( Foster-Turley, McDonald & Mason, 1990; Borgwardt & Culik, 1999). The Late Miocene otter S. beyi Peigné et al., 2008 , has a relatively primitive postcranial skeleton compared with those of modern otters, and for that reason it has been considered as ‘a terrestrial predator with poorly developed aquatic adaptations’ ( Peigné et al., 2008). Nonetheless, the limb bones of S. beyi , when compared with those of Te. riparius , are clearly much more robust, emphasizing the presence of different lifestyles amongst Late Miocene fossil otters. In fact, there are no traits that could define Te. riparius as having an aquatic lifestyle, with its postcranial anatomy most likely indicating a primitive morphology rather than special locomotor adaptations. The talus is relatively slender, with a long neck, more similar to those of mustelines such as G. gulo ( Fig. 16 View Figure 16 ) or Ma. martes than to those of otters (even A. cinereus shows a relatively more robust talus). Furthermore, the asymmetry of the talar trochlea, with the lateral lip proximally more developed than the medial one, and the relatively long talar neck are also seen in the mustelines, whereas otters show a more massive, symmetrical talar trochlea, and shorter necks. Compared with the analysed otters, the calcaneus of Te. riparius is more laterally flattened, with a less medially projected sustentaculum tali, indicating the existence of a narrower talus; also, the presence in Te. riparius of a relatively large depression for the muscle quadratus plantae, very reduced in other taxa, emphasizes its primitiveness. All these features define a primitive ankle, far from the typical otter morphology, even considering the semi-aquatic A. cinereus . Otters use all four limbs when swimming, but principally the hind limbs ( Wyss, 1987; Taylor, 1989) and that is the reason why their talar anatomy shows a marked differentiation from the primarily terrestrial, primitive mustelid model. Additionally, the relatively long lumbar series of Te. riparius , with craniocaudally short, almost triangular spinous processes, both features observed in the semi-arboreal martens, indicates the lack of aquatic adaptations. A very flexible back is not appropriate for aquatic locomotion owing to the necessity for a rigid lumbar region during swimming, when most of the thrust is generated by motions of the hind limbs and tail ( Tarasoff et al., 1972), which are more efficiently transmitted to the body by a short, inflexible lumbar spine. In this respect, it is remarkable that those extant species of Carnivora with triangular spinous processes on the lumbar vertebrae, such as martens, have strong interspinal muscles between the processes, something related to their use of a bound or half-bound to run, which implies strong flexion and extension of the column ( Gambaryan, 1974; Taylor, 1976, 1989). Those species that trot or gallop but rarely bound have rectangular lumbar spinous processes that nearly contact each other, therefore lacking interspinal muscles; however, they have strong interspinous ligaments, which are more efficient during a prolonged trot through the use of the energy accumulated in the ligaments when the column flexes to produce movement ( Taylor, 1989). The tail of Te. riparius seems to have been much less robust than those of otters, lacking the special structures related to the presence of the powerful muscles of the latter.

The metacarpals and metatarsals of Te. riparius are also relatively slender, although similar to those of A. cinereus and the small mustelines of the genus Martes , which probably indicates that all these taxa share a primitive, slender hand and foot.

In summary, Te. riparius represent a very primitive otter, completely different from the typical, aquatic otters such as Lu. lutra or Lo. canadensis . In fact, most of the postcranial features that suggest a semiaquatic adaptation, such as a pelvis with relatively short ilium; short femoral neck; lateral expansion of the greater trochanter of the femur; tibia with distinctly curved diaphysis; shortened limb bones; widening of bones in proportion to their lengths; or flattened phalanges ( Inuzuka, 2000; Schutz & Guralnick, 2007; Rybczynski, Dawson & Tedford, 2009), seen in typical otters, are absent in Te. riparius . Nevertheless, its dentition shows an otter-like pattern, with a low and elongated m1, a short P4, and a squared M1, which interestingly points towards the possibility that the aquatic lifestyle of otters could have appeared after the development, at least in a primitive fashion, of the distinctive dental morphology of this specialized group of mustelids.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.