Entimus sastrei, Viana

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1649/0010-065x(2002)056[0501:tnwgec]2.0.co;2 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15693579 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5F3F879C-FFE0-FFB1-FDC1-8EDFFEAE7F13 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Entimus sastrei |

| status |

|

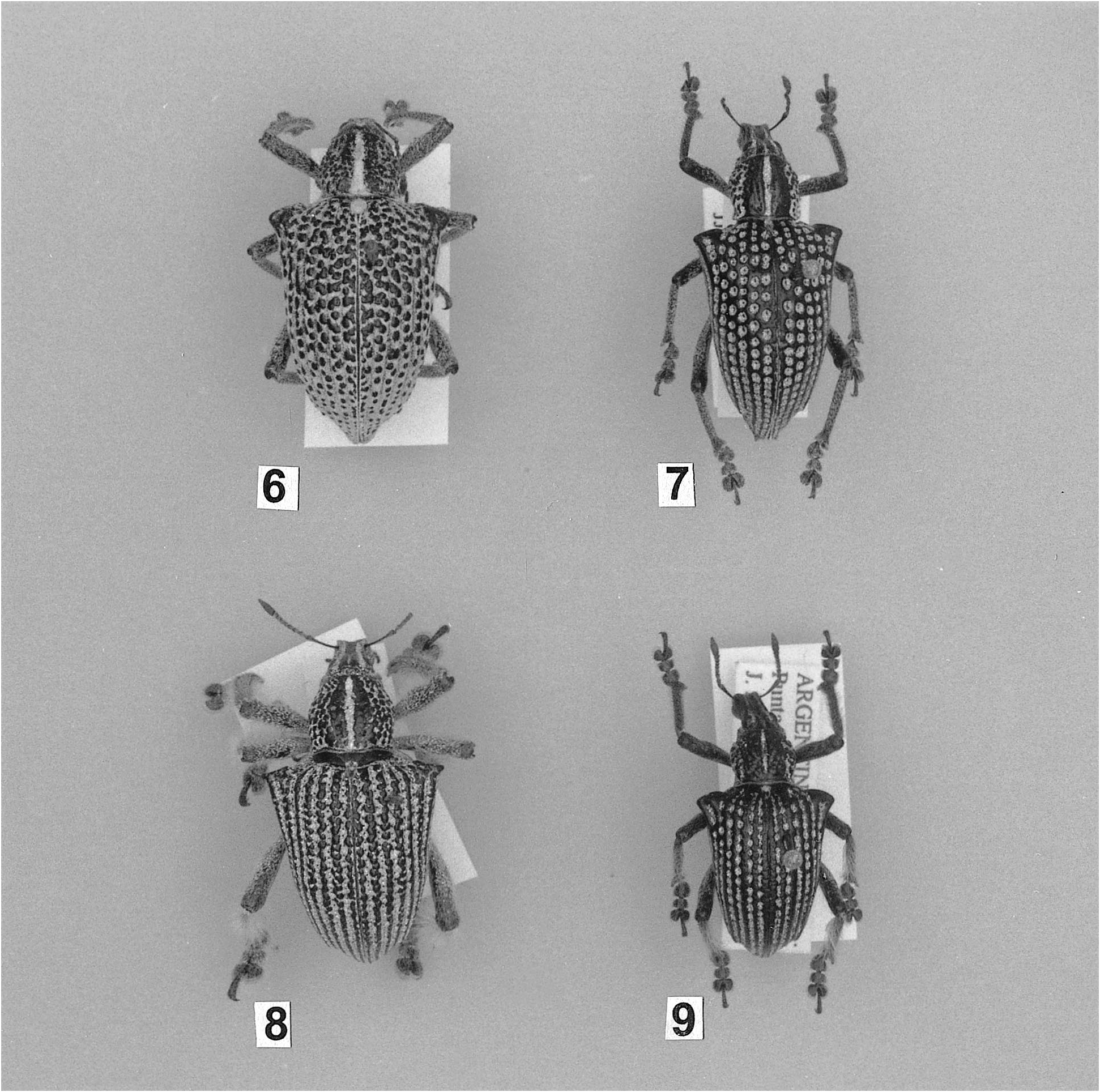

( Fig. 9 View Figs )

Entimus sastrei Viana 1958:6 View in CoL (= E. nobilis View in CoL of authors, misidentification, not Olivier 1790).

Entimus formosus Viana 1958:2 View in CoL , syn. nov.

Initially, I supposed that the specimens from Punta Lara ( Buenos Aires province, Argentina) belonged to the species E. sastrei Viana View in CoL , however, when I compared them with those of E. formosus Viana I View in CoL found that they all belonged to a single species. The few differential characters given by Viana (1958), e.g., development of pronotal granules, presence of scales on the elytral suture, or depth of elytral punctures, represent intraspecific variation.

Diagnosis. Frontal groove widened; pronotum wider than long, with acute postocular lobes, and decumbent setae; scutellum flat; elytra with rounded humeri, interstriae lacking rounded tubercles, and scarce to absent setae; scales elongateovate, uniformly covering striae imbricate, absent on intestriae; elytra lacking white bands; and male legs with abundant setae. Total length (pronotum + elytra): 15–36 mm.

Distribution. Argentina and Uruguay.

Material Examined. ARGENTINA. Buenos Aires: Punta Lara, I1928, C. Bruch coll., holotype of E. sastrei ( MACN), 20II1938, M. Bruzzone coll., 1 ( MLP) , 1939, C. Bruch coll., 4 paratypes of E. sastrei ( MACN), II1953, 1 ( MLP) , 30X1987, J. J. Morrone coll., 5 ( MZFC) ; Zárate , I1935, 1 ( MLP) , II1955, 2 ( MLP) . Corrientes: Santo Tome´ , Pellerano coll., 10 paratypes of E. formosus (MACN) , Entre Ríos: Río Martínez , II1953, 2 ( MLP) . Misiones: Depto. Concepción, Santa María , II1945, M. J. Viana coll., 1 ( MACN), X1947, M. J. Viana coll., holotype and two paratypes of E. formosus ( MACN), X1952, M. J. Viana coll., 1 ( MACN). Without more precise data. 1 ( MLP) .

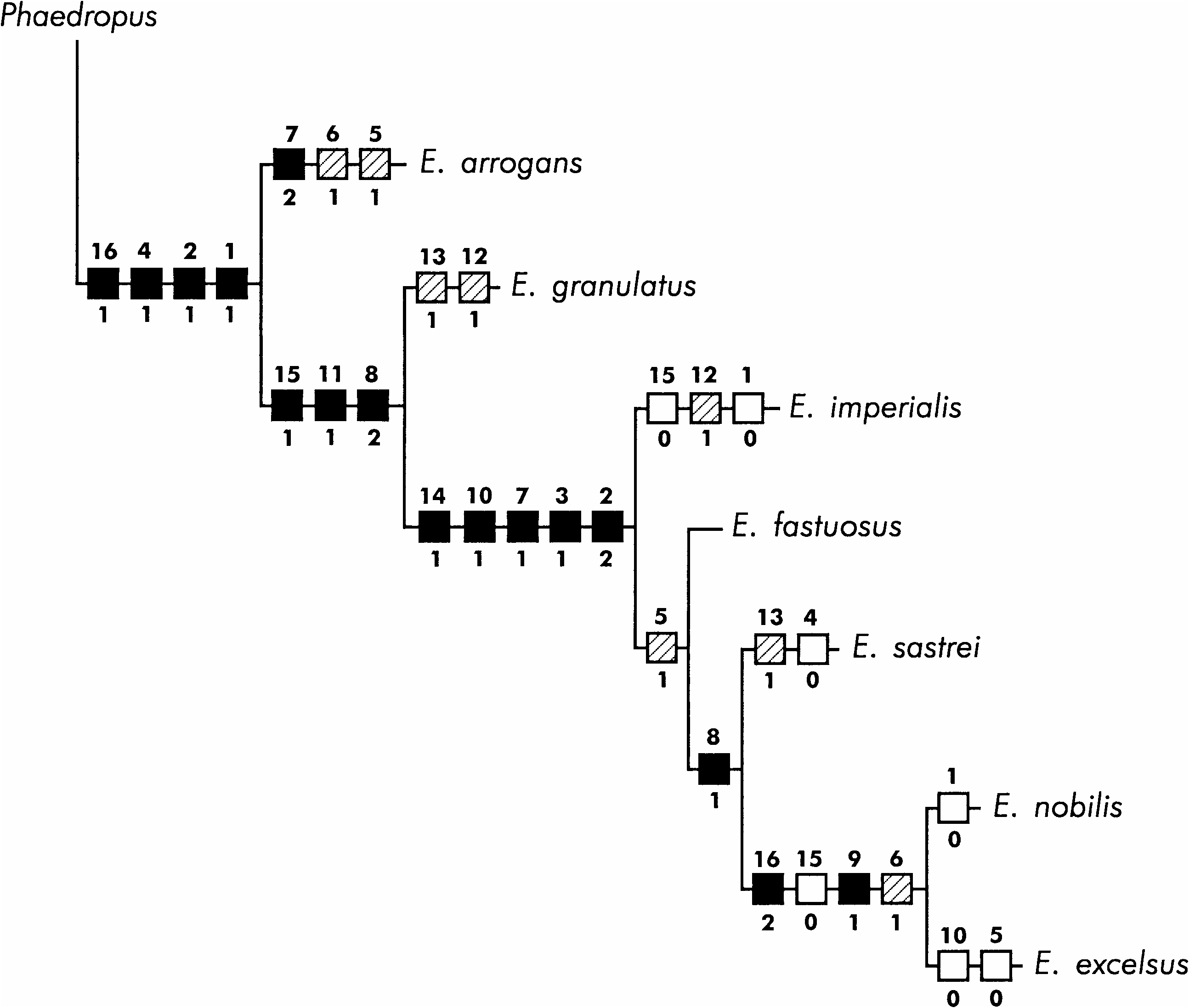

The cladistic analysis yielded four equally parsimonious cladograms, each with 33 steps, a consistency index of 0.60, and a retention index of 0.53. After successive weighting, a single cladogram resulted, with 105 steps, a consistency index of 0.89, and a retention index of 0.90. According to this cladogram ( Fig. 10 View Fig ), the species follow the sequence: E. arrogans , E. granulatus , E. imperialis , E. fastuosus , E. sastrei , E. nobilis , and E. excelsus . The clade including the latter five species is strongly supported by five synapomorphies and the species included in it are very similar.

In spite of the small number of specimens examined in this study, there are several localities reported by Vaurie (1952) and Viana (1958, 1968) which may be taken into consideration when speculating on the modes of speciation and analyzing the geographical distribution of the species of Entimus (see Fig. 11 View Fig ). According to the available data, E. arrogans (Mesoamerican) , E. granulatus (basically Amazonian), and E. sastrei (from northeastern Argentina) are allopatric, whereas the remaining four species are sympatric in southeastern Brazil. By comparing these distributions with their phylogenetic relationships, I hypothesize that E. arrogans and E. granulatus probably followed an allopatric mode of speciation, whereas the most likely mode for the latter four species is sympatric.

The isolated distribution and relatively small range of E. sastrei may imply that it evolved through either the peripheral isolate mode or the centrifugal mode of speciation. Predictions of the peripheral isolate model (either by waif dispersal, microvicariance, or range retraction) imply that the peripheral isolate possesses the symplesiomorphic character states that were present in the original population and autapomorphies that arose independently of other populations after isolation, whereas predictions of the centrifugal mode of speciation imply that the peripheral isolate should remain relatively plesiomorphic while the greater number of apomorphic character states should be present in the central population ( Frey 1993). If we consider the ancestor of E. nobilis + E. excelsus as the ‘‘central population’’ from which E. sastrei arose, the centrifugal mode of speciation seems to be the most plausible. Although E. excelsus also has a restricted range, based on the cladistic and biogeographic information available, it is not clear whether it also may have followed the latter mode of speciation.

The first dichotomy in the cladogram, separating the Mesoamerican species E. arrogans from the South American taxa, agrees with the results of Lanteri’s (1995) analysis of the weevil genus Ericydeus , also belonging to the tribe Entimini . This could be due to the vicariance between the Caribbean subregion ( sensu Morrone 1999 b) from the rest of the Neotropical region, as postulated by Amorim and Pires (1996) and Ron (2000). The second dichotomy, separating E. granulatus from the rest, agrees with a vicariant event between the Amazonian and the Parana + Chacoan subregions.

Within the clade including the remaining species, E. sastrei is distributed in the Parana flooded savannas ecoregion ( sensu Dinerstein et al. 1995), considered as a part of the Pampean province of the Chacoan subregion ( Morrone 2000). Usually Pampean taxa exhibit closer relationships with those of other Chacoan provinces, although there are cases where they show closer biotic links with the Parana subregion, for example the Entimini Cyrtomon and Priocyphus ( Lanteri 1990 a, b; Lanteri and Morrone 1991). Species of the latter two genera, however, are absent from the Parana flooded savannas ecoregion, so no biogeographic congruence is present. This lack of congruence also agrees with the biogeographic predictions of the centrifugal mode of speciation ( Frey 1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Entiminae |

|

Genus |

Entimus sastrei

| Morrone, Juan J. 2002 |

Entimus sastrei

| Viana 1958: 6 |

Entimus formosus

| Viana 1958: 2 |