Embates Chevrolat, 1833

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1100.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7C1F1264-5F23-4557-BFC2-4D015289CF7E |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/4540A14C-CF3B-9E63-B436-DCDFFBE23591 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe (2021-07-01 03:28:51, last updated by Plazi 2023-11-03 03:20:29) |

|

scientific name |

Embates Chevrolat |

| status |

|

Embates Chevrolat 1833: 18 View in CoL . Type species Embates caecus Chevrolat 1833 View in CoL , by subsequent designation under erroneous assumption of monotypy ( O’Brien & Wibmer 1982). Schönherr 1843: 150, 153 (treated as synonym of Ambates Schönherr View in CoL ); Champion 1907 (treated as nomen nudum); Hustache 1938 (treated as nomen nudum); O’Brien & Wibmer 1982 (treated as misspelling of Ambates Chevrolat 1835 View in CoL , spelling suppressed); Wibmer & O’Brien 1986 (treated as misspelling of Ambates Chevrolat 1835 View in CoL , spelling suppressed); AlonsoZarazaga & Lyal 1999 (original spelling reestablished); Prena 2003a (genus distinguished from Ambates Schönherr View in CoL ).

Ambates View in CoL ; Chevrolat 1835 [Appendix with list of species treated in Chevrolat 1833 –35]. Not available (deviation from original spelling neither mentioned or explained; see text below)

Ambates View in CoL ; Schönherr 1836: 278 (partim). Type species Ambates pictus Gyllenhal 1836 View in CoL , by original designation. Schönherr 1833 (nomen nudum), 1843; Chevrolat 1877, 1879; Gyllenhal 1836; Dejean 1837; Boheman 1843; Erichson 1847; Kirsch 1869, 1874; Pascoe 1880; Jekel 1883; Faust 1892; Champion 1907; Casey 1922; Günther 1936; Hustache 1938, 1939, 1950; Marshall 1946; Voss 1953, 1954; Kuschel 1955, 1983; Blackwelder 1957; Janczyk 1970; O’Brien & Wibmer 1982 (to subjective synonym of Embates Chevrolat 1833 View in CoL and homonym of Ambates Chevrolat 1835 View in CoL ; original spelling rejected); Wibmer & O’Brien 1986 (cat.); Marquis 1991; AlonsoZarazaga & Lyal 1999 (synonymized with Embates Chevrolat View in CoL ); Prena 2003a ( Ambates Schönherr View in CoL distinguished from Embates Chevrolat View in CoL and resurrected).

Drepanambates Jekel 1883 View in CoL [1882]: 85. Type species Peridinetus schoenherri Chevrolat 1882 , by subsequent designation ( Prena 2003a). Champion 1907 (synonymized with Ambates Schönherr 1836 View in CoL ); Hustache 1938 (genus resurrected); Casey 1922; Blackwelder 1947; Voss 1953, 1954; Weidner 1976 (cat.); O’Brien & Wibmer 1982; Wibmer & O’Brien 1986; AlonsoZarazaga & Lyal 1999. New synonymy.

Batames Casey 1922: 4 View in CoL . Type species Ambates solani Champion 1907 View in CoL , by original designation. Hustache 1938 (to subgenus of Ambates Schönherr 1836 View in CoL ); Voss 1954 (synonymized with Drepanambates Jekel View in CoL ); Prena 2003a. New synonymy.

Macrambates Casey 1922: 5 View in CoL . Type species Ambates melanops Champion 1907 View in CoL , by original designation. Hustache 1938 (to subgenus of Ambates Schönherr 1836 View in CoL ); Prena 2003a. New synonymy.

Cholinambates Casey 1922: 6 View in CoL . Type species Ambates cretifer Pascoe 1880 View in CoL , by original designation. Hustache 1938 (to subgenus of Ambates Schönherr 1836 View in CoL ); Prena 2003a. New synonymy.

Ambates (Ambatodes) Voss 1954: 302 . Type species Ambates sagax Voss 1954 View in CoL , by original designation. Wibmer & O’Brien 1986; Prena 2003a (synonymized with Embates Chevrolat View in CoL ).

The history of confusions concerning the names Ambates View in CoL and Embates View in CoL , their authorships, type species and interpretations is presented in Prena (2003a) and briefly summarized here. Chevrolat had adopted Schönherr’s manuscript name Ambates View in CoL (by explicitly citing its origin) in his own paper, spelled it Embates View in CoL in the text ( Chevrolat 1833) and Ambates View in CoL in the appendix of the same work (Chevrolat 1835). This nomenclatural act was generally disregarded in the literature because of supposed absence of a valid description. Subsequent studies in this group of weevils referred to Ambates Schönherr (1836) View in CoL . O’Brien & Wibmer (1982) recognized the formal validity of Embates Chevrolat View in CoL , but considered the original spelling a lapsus calami because of its deviation from that used in the appendix. AlonsoZarazaga & Lyal (1999) considered the suppression of the spelling Embates View in CoL as technically inconsistent with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and regarded Embates Chevrolat View in CoL a subjective senior synonym of Ambates Schönherr. The View in CoL latter was distinguished from Embates View in CoL and resurrected in Prena (2003a).

Drepanambates Jekel (1883) View in CoL is another genus that needs to be addressed in this context, because its cursory description referred to species of Embates View in CoL , Ambates View in CoL and species representing another, still undescribed genus, but failed to designate a type species. In order to preserve Jekel’s original intention and to suppress subsequent erroneous interpretations by Champion (1907) and Hustache (1938), I designated Peridinetus schoenherri Chevrolat as type species ( Prena 2003a). In this sense, Drepanambates View in CoL includes certain species that occur in the coastal rain forests between the Brazilian provinces Bahia and Santa Catarina, i.e. Ambates callinotus Chevrolat View in CoL , A. ephippius Chevrolat , Drepanambates amabilis Jekel View in CoL and Peridinetus schoenherri . They exhibit a falciform rostrum with a ventrally produced lateral edge, basally parallel pronotal sides and often slightly convergent elytral sides. However, these character states can be found in various combinations in species of Embates Chevrolat. My View in CoL study of approximately 150 species revealed no character state that could be used to divide Embates View in CoL into phylogenetically meaningful subunits. This is not surprising, because the great species diversity of Embates View in CoL and the close relationship to several genera with the same larval host favor a concept of young phylogenetic age. For this reason, I include Drepanambates Jekel View in CoL in Embates Chevrolat View in CoL as a new junior synonym.

The various genera near Ambates View in CoL erected by Casey (1922) were based generally on a cursory study of the figures in Champion (1907) and need no further comment. Anambates Casey View in CoL is a synonym of Pardisomus Pascoe ( Prena 2003b) View in CoL and Pycnambates Casey View in CoL is a synonym of Ambates Schönherr ( Prena 2003a) View in CoL . Batames Casey View in CoL , Macrambates Casey View in CoL and Cholinambates Casey View in CoL are new synonyms of Embates Chevrolat. View in CoL

Recognition. From other genera in the subfamily Baridinae , species of Embates can be distinguished by the following combination of character states: total length 3.0– 11.2 mm, integument smooth to finely punctate, covered by small scales often forming colorpattern, eyes flat, separated by width of rostrum at base, frontal fovea minute or absent, rostrum curved, 0.8–1.7 x longer than pronotum, basoventral edge of rostrum more or less produced, dorsal margin of antennal scrobe reaching ventral edge of rostrum, antennal club oblong, more than 2 x longer than wide, elytra subparallel to slightly convergent in basal half, at most only elytral interstriae 7–9 costate, some species with callosities in interstriae 3–5, pygidium covered by elytral apices, procoxae contiguous, prosternal channel very shallow or absent, its lateral edge vestigial, femora expanded dorsoventrally, all equally dentate ventrally, aedeagal flagellum longer than body of aedeagus, male sternite 8 entire and 3lobed.

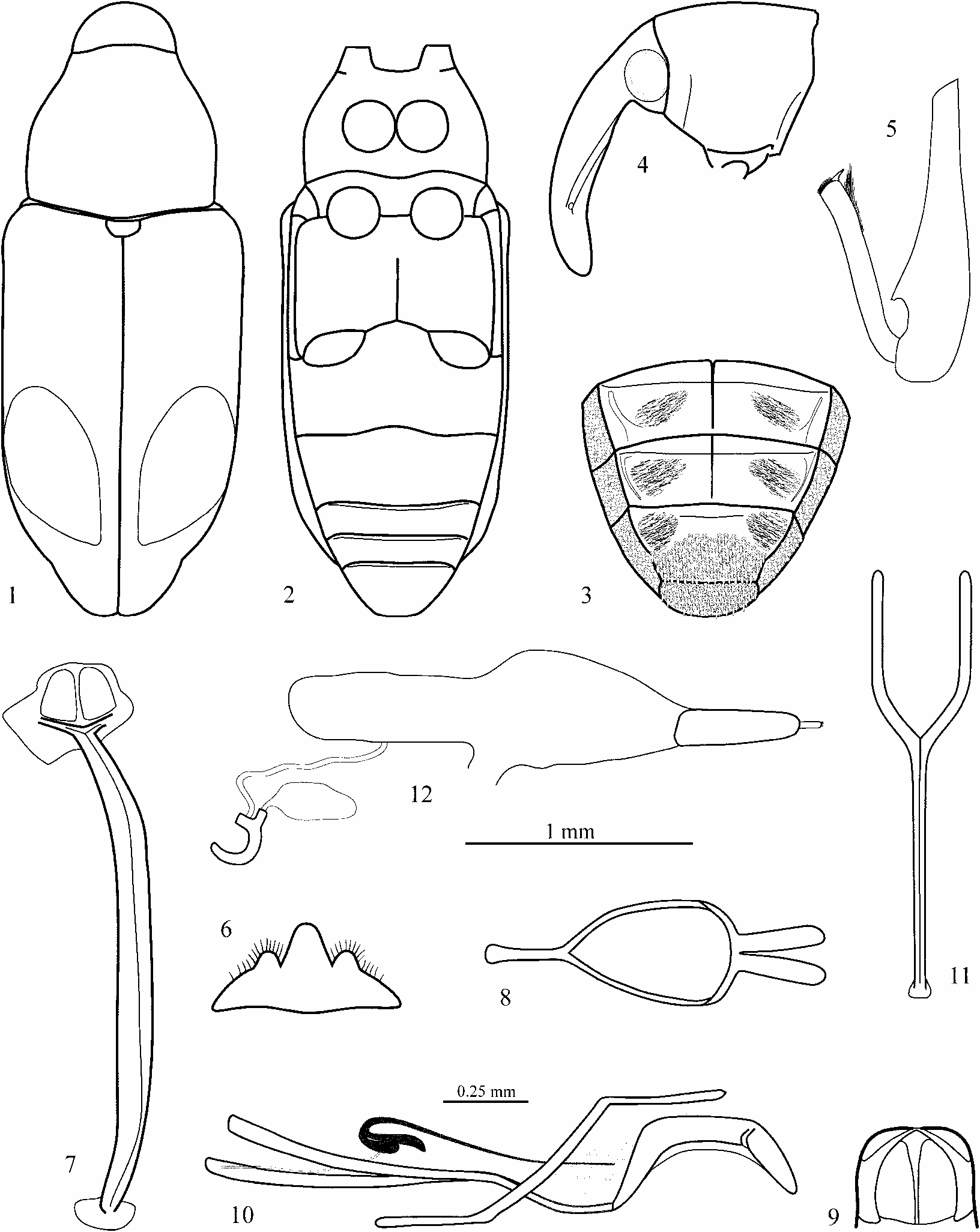

Redescription of adult. Habitus: moderately elongate to stout, total length 3.0– 11.2 mm. Color: integument various shades of rufous to black; basic vestiture of small scales moderately dense, scales sometimes extremely minute, majority of species with pronotal and elytral colorpattern of white, yellow, reddish, brown or black scales (see last section further below about colorpattern), scales variously dense on venter and legs. Head: spherical, retractile to eyes, finely punctate, frons as wide as rostrum at base, frontal fovea minute or absent, transition between head and rostrum slightly depressed, shape of rostrum varied from slender and subcylindrical to moderately thick and falciform, curved, often slightly more so over antennal insertion than at base, basolateral margin roundly edged to distinctly produced, length of rostrum 0.80–1.71 x pronotal length, length of anteantennal portion of rostrum 0.22–0.58 x total rostral length, antennal insertion in males slightly more distally than in females, dorsal margin of antennal scrobe reaching ventral margin of rostrum; funicle of 7 segments, length of segment 2 subequal to or longer than segment 1, club oblong ovate to subcylindrical, 2–4 x longer than wide. Pronotum: length 0.74–1.07 x maximum width, widest in basal half, sides subparallel to round in basal half, gradually to abruptly narrowed distally and shortly tubulate in front (ventrally more than dorsally), dorsomedian frontal lobe weakly produced, often slightly notched medially; basal margin weakly rounded, disk punctate, interspaces smooth, finely rugose or granulate. Scutellum: welldefined, separate, size moderate, shapes various and variable. Wings: welldeveloped. Elytra: length 1.23–2.27 x width of humeri, width 1.12–1.65 x maximum pronotal width, sides subparallel to slightly convergent in basal half, gradually to roundly narrowed in distal half, apices conjointly to separately rounded, covering pygidium, preapical callus present, variously developed, striae fine to partially obliterated, strial punctures subtle, interstriae flat, at most 7–9 finely costate, 3–5 with callosities in some species. Legs: moderately stout to slender (corresponding to body shape), procoxae contiguous, femora moderately expanded dorsoventrally in distal half, pro, meso and metafemora equally 1 dentate in distal third ( Fig. 5 View FIGURES 1–12 ), tibiae variously curved, ventrodistally with cluster of hairs, tibial mucro developed, premucro absent, tarsal segment 3 2lobed, wider than segments 1 and 2, segment 5 (pretarsus) rounded ventrodistally (pointed in E. scambus ), tarsus with 2 claws, claws arcuate and separate at base or straight and approximate, secondary (inner) tarsal tooth absent. Venter ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1–12 ): procoxae contiguous, prosternal channel obsolete, feeble lateral ridge usually present; surface between prosternum and mesosternum discontinuous, distal abdominal ventrites short, with sutures flexible. Male ( Fig. 6–10 View FIGURES 1–12 ): sternite 8 entire, membranous, 3lobed, lateral lobes pigmented and with fringe of setae; sternite 9 slightly curved, lateral arms asymmetric, short; tegmen with parameres approximate at base or (rarely) fused; body of aedeagus approximately 1.5–4.0 x longer than wide, symmetric, curved in lateral view; apodemes slender, 1.8–4.0 x longer than aedeagus, curved outward in basal third, connection to body of aedeagus sclerotized; internal sac moderately to very long, aedeagal flagellum present, longer than body of aedeagus, sclerotized, base thicker and curved toward front, transition between base and flagellum continuous or abrupt, ejaculatory duct attached to recurved base of flagellum outside internal sac, inner face of base of flagellum with appendage which is attached to internal sac and holds flagellum in place. Female ( Fig. 11–12 View FIGURES 1–12 ): sternite 8 symmetric, with 2 basally diverging, sclerotized arms; length of vagina, bursa and spermathecal duct subequal, duct inserted ventrally at midlength of bursa, hemisternite pigmented, stylus with 4–8 distal setae, spermatheca sickleshaped, sclerotized. Stridulatory organ: present in both sexes, ventral subapical portion of both elytra with stridulatory files, tergite 8 and basal portion of tergite 7 with decumbent scales in coarse, irregular punctures functioning as plectra ( Fig. 3 View FIGURES 1–12 ).

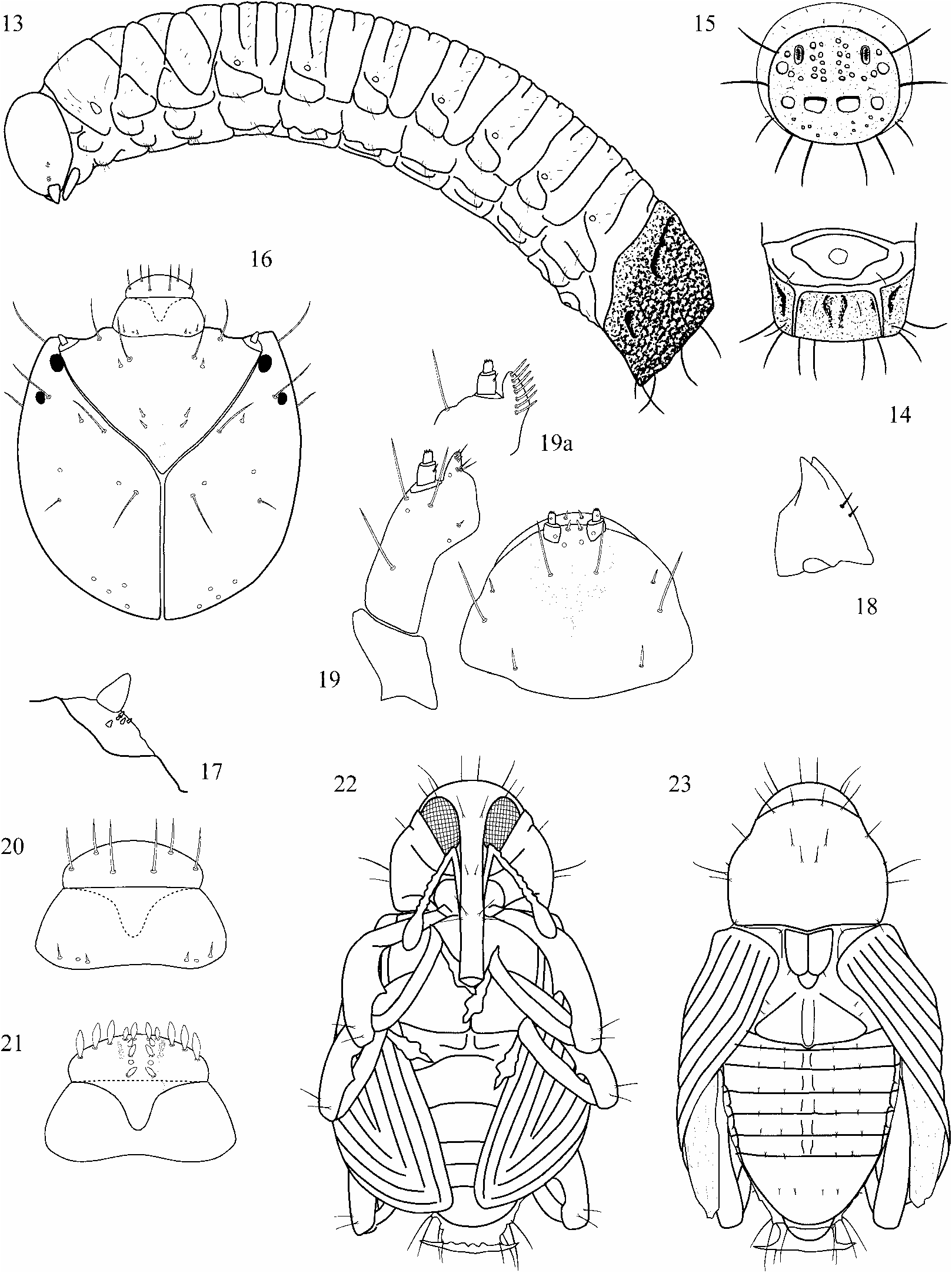

Description of larva. ( Fig. 13–21 View FIGURES 13–23. 13–21 ). Habitus: size of specimen figured 9.0 mm x 1.9 mm, body slightly curved, cylindrical; abdominal segment 8 modified to strongly sclerotized pseudocaudal segment, segments 9 and 10 moved ventrad; cuticle finely asperate, creamy white; setae light brown, translucent, rather short, inconspicuous. Head: nearly orthognath, amberbrown, without internal epicranial ridge; slightly longer than wide, 1.0 mm wide; both pairs of stemmata distinct (pigments may fade when slidemounted); accessory appendage of basal antennal segment conical, 2 x longer than wide; frontal suture distinct, endocarinal line half as long as frons; 5 pairs of frontal setae, setae 1–3 very short, setae 4–5 long and subequal; 5 pairs of dorsal epicranial setae, seta 4 very short, seta 2 moderately long, others long and subequal; 2 pairs of long lateral epicranial setae; 4 pairs of very short posterior epicranial setae; 2 pairs of ventral epicranial setae, seta 1 short, seta 2 of moderate length; clypeus 2 x wider than long, subconical, 2 clypeal setae of unequal length; anterior margin of labrum broadly rounded, 3 pairs labral setae, seta 1 longest; labral rods barshaped, subparallel, hypopharyngal lining with 2 pairs of broad anteromedian setae, 3 pairs of anterolateral setae 2 x longer than anteromedian setae, 2 pairs of short median setae and 1 pair of sensilli in between; mandible with two apical teeth of equal size, two setae arranged longitudinally; maxilla with palpus 2segmented, basal segment with short seta and two sensilli, mala with 3 moderately long and 2 short ventral setae and row of 7 dorsal setae of equal size; labium with palpus 2segmented, premental sclerite 3dentate, basal process of moderate length, postlabial seta 2 much longer than setae 1 and 3. Thorax: pronotum partially pigmented, with 3 pairs of long and 7 pairs of short setae, dorsopleural seta absent, 2 ventropleural setae of unequal length, spiracle 2cameral, airtubes annulated, arranged vertically, 2 long and 4–5 short pedal setae, 1 pair of short mediosternal setae; meso and metathorax with 2 pairs of prodorsal and 3 pairs of postdorsal setae, 2 short spiracular (alar) setae, 1 long dorsopleural seta, 1 long ventropleural seta, 2 long and 4 short pedal setae, 1 pair of short mediosternal setae. Abdomen: spiracles 2cameral, airtubes annulated, small and horizontal at segments 17, vertical on sclerotized caudal plate formed by segment 8, connected with tracheal system and with respiratory function; segments 1–7 with 1 pair of short prodorsal and 5 pairs of postdorsal setae of unequal length, 2 short spiracular (alar) setae, 2 dorsopleural setae of unequal length, 2 ventropleural setae of unequal length, 1 laterosternal seta of moderate length, 2 pairs of short sternal setae; segment 8 sclerotized, surface rugose with elongate dorsolateral and short lateral pits, caudal plate with spherical depressions, 4 pairs of long peripheral setae along edge of disk, 2 pairs of ventrolateral setae of unequal size, 1 pair of ventral setae of moderate size, 0–3 pairs of minute dorsal setae, 1 minute seta on disk below spiracle; segment 9 ventral, with 1 pair of setae of moderate size; anus ventral, with 4 indistinct lobes. Material: 3 putative E. cretifer from stem of P. cenocladum (here illustrated), 2 putative E. cordiger from stem of P. cenocladum , 5 putative E. polymorphus altrimsecus from stem of P. obliquum , 1 putative E. pseudobumbraticus from stem of P. pseudobumbratum ; 3 putative E. discordabilis from stem of P. sanctifelicis , 1 putative E. paludicola or E. crinipes from stem of P. imperiale ; total 15 specimens, 6 of them dissected and slidemounted; identifications are based on associations with adult specimens and their foodplants. Additional larvae with membranous abdominal segment 8 were collected from stems of P. augustum and P. euryphyllum . Those may belong to E. sinuatus and E. euchasma , respectively, or to unidentified species of Peridinetus .

Description of pupa ( Fig. 22–23 View FIGURES 13–23. 13–21 ). Habitus: length of specimen figured 5.2 mm, pronotum 1.8 mm wide; setae long, on distinct tubercles. Head: retracted, visible in dorsal view, 3 pairs of long setae; rostrum reaching middle of metasternum, 3 pairs of long and 1 pair of moderate setae, mandibular setae absent. Thorax: pronotum slightly transverse, widest in basal onethird, sides rounded toward front, apex slightly tubulate, basal margin very slightly produced, disk convex, 8 pairs of long and 1 pair of short setae; mesonotum with scutellum distinct, 2 pairs of setae; metanotum sulcate medially, 2 pairs of setae; pterotheca 1 with surface of intervals smooth, pterotheca 2 slightly longer than pterotheca 1; femora 1dentate, each with 2 setae, tarsal setae absent. Abdomen: segments 1–7 with 2 pairs of postdorsal, 1 pair of lateral and 1 pair of minute ventral (not seen on segments 1–4) setae, segment 8 with 1 pair of long postdorsal and 2 pairs of lateral setae, segment 9 with 1 pair of long lateral setae and dorsolateral pseudocerci. Material: 1 mature specimen of E. chelys collected from stem of P. cenocladum ; identification based on faint colorpattern and association with plant.

Life history. Species of Embates occur primarily in disturbed habitats of evergreen forests, generally not above 2600 m. A few species dwell in open habitats, among them E. solani , E. marginatus and E. vestitus . Adult specimens are diurnal and can be found on their host plants throughout the year. Plants in Piperaceae could be confirmed with reasonable confidence as diet for the majority of the Costa Rican species ( Marquis 1991, this study) and as larval host for approximately six species. Species of Piper (including Pothomorphe ) represent the principal host plants, while at least E. flavolimbatus and E. peperomiae are associated with species of Peperomia . Most adult species are oligophagous in particular groups of hosts, while some appear to be strictly monophagous. However, local subpopulations of oligophagous species may exhibit a clear preference for a particular species of host plant. A comprehensive concept about the phylogeny of the neotropical species of Piper is not available. My experience is that Burger’s (1971) provisional arrangement shows much agreement with the plantweevil associations found by Marquis (1991), and my observations. Species with palmately veined leaves (e.g. Piper pseudolindeni , P. retalhuleuense , P. reticulatum , P. sanctum ; with the notable exception of P. marginatum ) are visited rarely by species of Embates . The remaining species of Piper can be divided into two groups based on the mode of their distal growth. The shootapex and the new leaf emerge either from within the leafbase at the flowering nodes, or from within the prophyll and free of the leafbase at the flowering nodes ( Burger 1971). Despite oligophagy, almost all species of Embates seem to be restricted to one or the other of the two groups, while size, shape, venation and texture of the leaf exert little influence on the plant selection. The same observation holds for species in Ambates , Pantoteles and Peridinetus (personal data). Adult weevils of these four genera often can be found feeding or resting in characteristic holes made in the leafblade ( Fig. 24 View FIGURE 24 ), thereby exposing their flanks and mimicking fallen flowers, bracts, seeds or excrement. Oviposition has not been observed to my knowledge. The eggs are relatively large, elongate, and produced in low numbers. Larval development takes place in the soft or slightly woody tissue of the stem, rarely in the petiole or in the root. The larva tunnels the interior of the stem without giving any external evidence of its presence except of an indistinct oviposition hole. Debris is disposed within the tunnel, where pupation takes place without a cocoon. The hatched weevil prepares an exit hole for leaving the interior of the host plant. By that time, the infested part of the host can be damaged to a degree that inhibits further terminal growth of the stem. Embates vanus is known to affect Piper nigrum (a cultivated oriental species) in Bolivia (E. Ramos, pers. comm.). No information is available about the development of the species associated with Peperomia .

Sexual dimorphism. Female specimens generally have a slightly longer, less sculptured rostrum with the antenna inserted slightly more basally compared to male specimens. Sexing of specimens can be done in most cases based on the degree of convexity of the basal ventrites. In a few cases, males can be recognized by the 1) more elongate antennal club (e.g. E. discordabilis ), 2) notched and pilose ventrite 5 (e.g. E. pseudobumbraticus ), 3) fringe of hairs on the ventral tibial edge (e.g. E. cretifer ), or 4) enlarged protibial mucro (e.g. E. sinuatus ). The pronotum is generally of subequal size in both sexes, while it exhibits dimorphism in various species of Ambates and Pardisomus .

Morphological variation. Apart from a few cases of nonsystematic deviation probably caused by injury at immature stages, some systematically occurring variations were observed. Most noteworthy is the significant relationship between the altitude of the collecting site and the body proportion of E. sinuatus . Figure 25 View FIGURE 25 illustrates this relationship for specimens collected along a 30 km long transect on the northern slope of Volcan Barva in Costa Rica. Specimens from high elevations are more slender than specimens collected at lower elevations (Fig. 80, 81). The same relationship holds for specimens from other regions ( Fig. 25 View FIGURE 25 ). On the Pacific side of the Costa Rican Cordillera de Talamanca, with more seasonal weather conditions, this effect can be accompanied by a modification of the colorpattern (see next paragraph). It is possible that the local temperature contributes to these variations, for instance by a prolonged larval development in cooler habitats. Similar observations on the possible effects of altitude on the body size were made for species of Pantoteles ( Prena 2001) and Ambates ( Prena 2003a) . The currently nonquantified contribution of environmental and genetic variables to the prevailing heterogeneity of adult specimens, particularly in geomorphologically heterogeneous habitats, can render the identification of some species a delicate issue when insufficient material is available for comparison.

Colorpattern. The presence of small scales and their frequent arrangement forming intriguing ornamental patterns prevails in most species in and near Embates . Champion (1907) used the colorpattern in his key for pragmatic reasons. Nevertheless, he was aware of the close relationship of several species with seemingly unrelated vestiture. Later authors, in particular Casey (1922) and Voss (1953, 1954), implied a greater taxonomic value of the colorpatterns and based new genusgroup names on them. A more comprehensive study of these patterns now demonstrates their compound nature. The material available gives numerous examples, in particular in complexes of imperfectly separated species, that allow for tracing the origin of the various components of the colorpattern. It is concluded here, that the primitive condition was a dark elytral macula encircled by a thin line of lightcolored scales. This condition is preserved in several species near E. caeca and E. sagax . These species also provide evidence that the lightcolored circumambient line disintegrated into single elements ( Fig. 26, 28 View FIGURES 26–33 ). It was the modification of these elements, in particular the antemacular and the postmacular elements, that led to the immense diversity of colorpatterns in the Ambatini ( Fig. 29–33 View FIGURES 26–33 ). Modifications included width, length, shape, bearing and position of each element, as well as color, size and density of the scales. In some cases, the basic vestiture dwindled to microscopic scales, so that the ante and postmacular elements dominate the colorpattern, such as in E. cretifer (Fig. 177) and E. paludicola (Fig. 200). In other cases, the ante and postmacular elements merged with the basic vestiture, such as in E. burgeri (Fig. 93) and E. polymorphus zeledonensis (Fig. 183d). Slight modifications of a single component may have a tremendous effect in complex colorpatterns, for example in E. sinuatus and E. belti . It can be said generally, that the dark elytral macula (if present) tends to vary rather little, while the adjacent lightcolored elements exhibit much more variability, often clinal and occasionally extreme in extent. The nature of this variation is thought to be a combination of environmental factors, such as the weather conditions during larval development and metamorphosis, and various degrees of genetic heterogeneity in the population.

Alonso-Zarazaga, M. A. & Lyal, C. H. C. (1999) A world catalogue of families and genera of Curculionoidea (Excepting Scolytidae and Platypodidae). EntomoPraxis S. C. P., Barcelona, 316 pp.

Blackwelder, R. E. (1947) Checklist of the Coleopterous insects of Mexico, Central America, the West Indies, and South America. Part 5. Bulletin United States National Museum, 185, 765 - 925.

Boheman, C. H. (1843) In: Schonherr, C. J.

Burger, W. (1971) Flora Costaricensis 35 (Piperaceae). Fieldiana, Field Museum of Natural History, 227 pp.

Casey, T. L. (1922) Studies in the Rhynchophorous subfamily Barinae of the Brazilian fauna. Memoirs on the Coleoptera, 10, 1 - 520.

Champion, G. C. (1907) Insecta. Coleoptera. Rhynchophora. Curculionidae. Curculioninae (continued). In: Champion, G. C. (1906 - 1909) Biologia Centrali-Americana. Vol 4, part 5, 137 - 240.

Chevrolat, A. (1833) Coleopteres du Mexique, fasc. 1. Strasbourg, 25 pp. [appendix with list of species issued as fasc. 4 in 1835]

Chevrolat, A. (1877) Diagnoses de nouvelles especes de Curculionides du genre Ambates. Annales de la Societe Entomologique de France, ser. 5, 7, 441 - 346.

Chevrolat, A. (1879) Descriptions de nouvelles especes de Coleopteres de la famille des Curculionides. Bulletin de la Societe Entomologique de France, CXLVIII - CL.

Dejean, P. F. M. A. (1837) Catalogue des Coleopteres de la collection de M. le Comte Dejean, Paris, I - XIV, 1 - 503.

Gunther, K. (1936) Uber Kafer der von S. und I. Wahner am oberen Amazonas gesammelten Insek- tenausbeute. Entomologische Rundschau, 53, 271 - 276.

Gyllenhal, L. (1836) In: Schonherr, C. J.

Hustache, A. (1938) Curculionidae, Barinae. In: Schenkling, S. (Ed.) Coleopterorum Catalogus, Pars 163, Verlag fur Naturwissenschaften, W. Junk, ' s-Gravenhage, 219 pp.

Janczyk, F. (1970) Neue Curculioniden der Zoologischen Sammlung des Naturhistorischen Museums Wien. Koleopterologische Rundschau, 48, 51 - 55.

Jekel, H. (1883) Notes sur le travail de M. Chevrolat concernant les Peridinetus. Annales de la Societe Entomologique de Belgique, 26 [1882], 84 - 86.

Kirsch, T. (1869) Beitrage zur Kaferfauna von Bogota. Berliner Entomologische Zeitschrift, 12 [1868], 177 - 214.

Kirsch, T. (1874) Beitrage zur Kenntniss der Peruanischen Kaferfauna auf Dr. Abendroth's Sammlungen basirt. Berliner Entomologische Zeitschrift, 18, 385 - 432.

Marquis, R. J. (1991) Herbivore fauna of Piper (Piperaceae) in a Costa Rican wet forest: diversity, specificity, and impact. In: Price, P. W., Lewinsohn, T. M., Fernandes G. W. & Benson W. W. (Eds.) Plant-Animal Interactions: Evolutionary ecology in tropical and temperate regions, John Wiley & Sons, 179 - 208.

Marshall, G. A. K. (1946) Taxonomic notes on Curculionidae (Col.). The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, ser. 11, 13, 93 - 98.

O'Brien, C. W. & Wibmer, G. J. (1982) Annotated checklist of the weevils (Curculionidae sensu lato) of North America, Central America, and the West Indies (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, 34, I - IX, 1 - 563.

Pascoe, F. P. (1880) New Neotropical Curculionidae. Part III. The Annals and Magazine of Natural History, ser. 5, 6, 176 - 184.

Prena, J. (2001) A revision of the neotropical weevil genus Pantoteles Schonherr (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Baridinae). Transactions of the American Entomological Society, 127, 305 - 358.

Prena, J. (2003 a) The Middle American species of Ambates Schonherr (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Baridinae). Beitrage zur Entomologie, 53, 161 - 192.

Prena, J. (2003 b) The Pardisomus species (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Baridinae) from Costa Rica, with descriptions of four new species and one larva. Beitrage zur Entomologie, 53, 193 - 210.

Schonherr, C. J. (1833) Genera et species curculionidum cum synonymia hujus familiae, Vol. 1 (1). Roret, Paris; Fleischer, Lipsiae, I - XV, 1 - 381.

Schonherr, C. J. (1836) Genera et species curculionidum cum synonymia hujus familiae, Vol. 3 (1). Roret, Paris; Fleischer, Lipsiae, 1 - 505.

Voss, E. (1953) Neue und bemerkenswerte Curculioniden aus Colombien und Bolivien. (Col. Curc.). Entomologische Mitteilungen aus dem Zoologischen Staatsinstitut und Zoologischen Museum Hamburg, 2, 55 - 84.

Voss, E. (1954) Curculionidae (Col.). In: Titschack, E. (Ed.) Beitrage zur Fauna Perus IV, 193 - 376.

Weidner, H. (1976) Die entomologischen Sammlungen des Zoologischen Instituts und Zoologischen Museums der Universitat Hamburg, IX. Teil, Insecta VI. Mitteilungen aus dem Hamburgischen Zoologischen Museum und Institut, 73, 87 - 264.

Wibmer, G. J. & O'Brien, C. W. (1986) Annotated checklist of the weevils (Curculionidae sensu lato) of South America (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, 39, I - XVI, 1 - 563.

FIGURE 25. Relationship between elevation of collecting site and metric proportion of elytron in local populations of E. sinuatus (r²= 0.48, p<0.001, n=215)

FIGURES 1–12. E. caecus: 1, habitus and colorpattern, dorsal; 2, thorax and abdomen, ventral; 3, posterior tergites, dorsal; 4, head and prothorax, lateral; 5, metafemur and tibia; 6, sternite 8, male; 7, sternite 9, male; 8, tegmen; 9, apex of aedeagus, dorsal; 10, aedeagus, lateral; 11, sternite 8, female; 12, female genital tract, lateral

FIGURES 13–23. 13–21, Lateinstar larva of putative E. cretifer: 13, habitus, lateral; 14, abdominal segments 8–10, ventral; 15, abdominal segment 8, caudal; 16, head capsule, frontal; 17, antenna; 18, right mandible, dorsal; 19, maxilla and labium, ventral and (19a) dorsal; 20, clypeus and labrum; 21, epipharynx. 22–23, pupa of E. chelys: 22, habitus, ventral; 23, habitus, dorsal.

FIGURES 26–33. Examples for dorsal colorpatterns in species of Embates (for further explanations see in the text). 26–28, species with dark elytral macula preserved: 26, E. sagax, Peru, with elytral macula with circumferential line entire; 27, E. delicatulus, Bolivia, with elytral maculae and postmacular elements merged across suture, antemacular element obliterated; 28, E. species #91, Colombia, with narrow antemacular and wide postmacular elements. 29–33, species with dark elytral macula merged with basic vestiture: 29, E. obliquatus, Peru, with antemacular element obliterated, postmacular element welldeveloped and humeral streak present; 30, E. rhombifer, Costa Rica, with ante and postmacular elements wide, fused with humeral streak and demarking rhomboid pseudomacula on disk; 31, E. quadrilineatus, Guyana, with perfectly continuous vitta composed of ante and postmacular, humeral and apical elements; 32, E. species #75, Ecuador, with postmacular element obliterated, antemacular and apical elements modified to fasciae; 33, E. species #101, Peru, with antemacular, humeral and apical elements reduced to small spots, postmacular element disintegrated in two small spots.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Embates Chevrolat

| Prena, Jens 2005 |

Ambates (Ambatodes)

| Voss, E. 1954: 302 |

Batames

| Casey, T. L. 1922: 4 |

Macrambates

| Casey, T. L. 1922: 5 |

Cholinambates Casey 1922: 6

| Casey, T. L. 1922: 6 |

Embates Chevrolat 1833: 18

| Chevrolat, A. 1833: 18 |