Alionchis jailoloensis Goulding & Dayrat, 2018

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5358903 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B04A2DD9-91C2-48D1-9EB2-965D3FFBF879 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0702712A-FFFB-DA55-FCFF-D8524C931078 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Alionchis jailoloensis Goulding & Dayrat |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Alionchis jailoloensis Goulding & Dayrat View in CoL , new species

( Figs. 3–7 View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig View Fig )

Type locality. Halmahera, Jailolo, 12°28.78′ S, 130°54.75′ E, station 218, Sonneratia and Rhizophora mangrove near a creek.

Type material. Holotype, 43/ 22 mm [5137], designated here ( UMIZ 00117 ).

Additional material examined. Indonesia, Halmahera, Kao, 01°09.48′N, 127°54.14′E, 5 specimens (51/30 [5039], 48/24 [5040], 45/27 [5023], 63/35 [#1], and 29/19 [5093] mm), station 208, mangrove by the beach, soft mud with Rhizophora , Avicennia and Nypa palms ( UMIZ 00118); Halmahera, Jailolo, 01°03.76′N, 127°28.14′E, 2 specimens (64/28 [5135] and 33/19 [5136] mm), station 218, Sonneratia and Rhizophora mangrove near a creek ( UMIZ 00119); Halmahera, Gamkonora, 01°26.91′N, 127°31.63′E, 3 specimens (61/31 [5028], 69/34 [6083] and 23/27 [6084] mm), station 219, mostly Rhizophora mangrove with a mix of open sandy and muddy areas ( UMIZ 00120).

Distribution. Halmahera, eastern Indonesia.

Etymology. The specific name jailoloensis comes from the type locality, the small port of Jailolo, on Halmahera’s western coast. Jailolo also happens to be one of the former names of the entire Island of Halamahera.

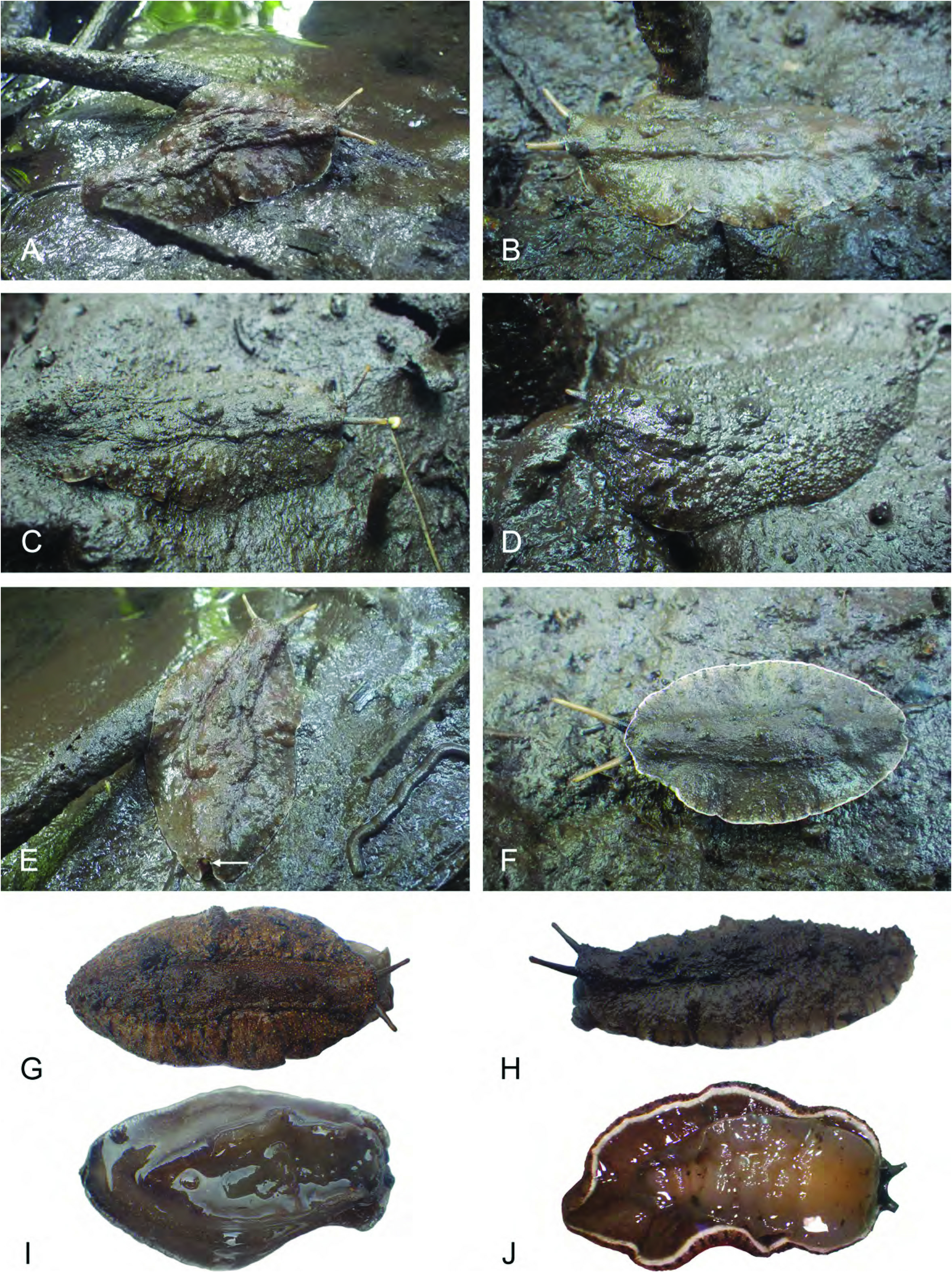

Habitat ( Fig. 3 View Fig ). Alionchis jailoloensis lives on open patches of mud in mangrove forests, where trees are not too close together. It typically is found on dark mud saturated with water, near Nypa , Avicennia , Sonneratia or Rhizophora . Animals usually are together in small clusters, rather than scattered randomly in the mangrove.

Colour and morphology of live animals ( Fig. 4 View Fig ). Natural colour of live animals usually observed without having to wash off any mud. Dorsal notum colour usually dark brown, but occasionally orangish-brown or red. Hyponotum (ventral) brown or grey-brown with small flecks of white and white margin. Foot brown or grey-brown.

Animal oval, slightly flattened, often contracts when disturbed. Dorsal notum granular. Papillae with so-called ‘dorsal eyes’ present, including a slightly raised central papilla. Between eight and fifteen eye papillae present, with three or four eyes per papilla. Eye papillae distributed near midline of notum. Animals occasionally dig into mud when approached and may completely disappear.

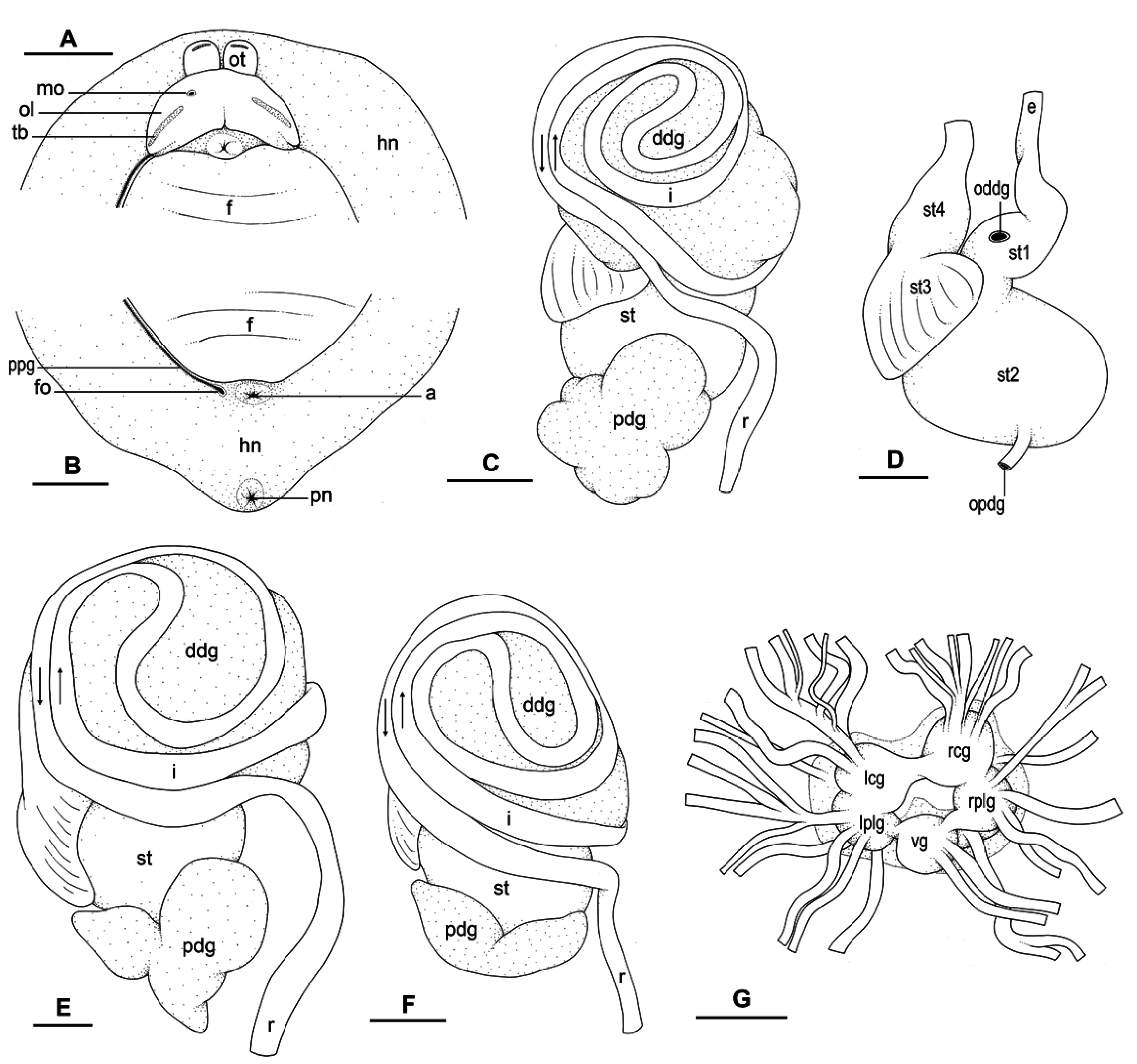

External morphology ( Fig. 5A, B View Fig ). Dorsal gills absent. Hyponotum width about one third of animal width, but hyponotum may be hidden anteriorly by foot. Anus posterior, median, close to edge of pedal sole. Female opening very close to anus. Peripodial groove runs longitudinally at junction between foot and hyponotum on right side (left in ventral view), from buccal area to posterior end, and ending with female opening. Pneumostome median, at posterior end of ventral hyponotum. Eyes at tip of paired ocular tentacles. A pair of oral lobes above mouth, each with an elongated (transversal) bump, likely with sensitive receptors. Male opening inferior to right ocular tentacle.

Visceral cavity and pallial complex. Visceral cavity not pigmented. Heart enclosed in pericardium, on right side of visceral cavity, slightly posterior to middle. Large, anterior, ventricle becomes large aorta that branches into smaller vessels delivering blood to visceral organs. Posterior auricle significantly smaller than ventricle. Pericardium communicates through small hole with right part of renalpulmonary complex. Kidney intricately attached to pulmonary cavity and more or less symmetrical.

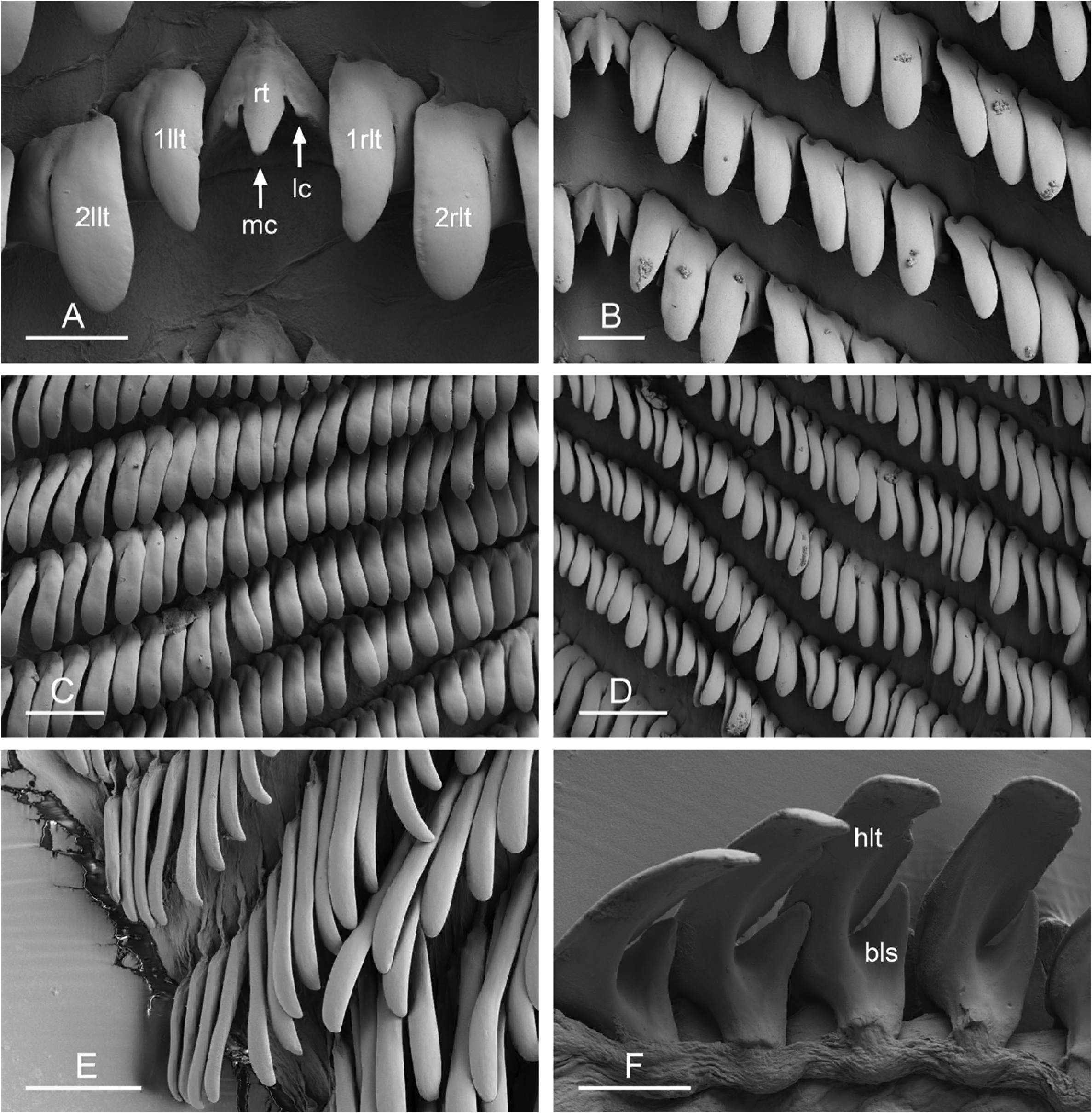

Digestive system ( Figs. 5 View Fig , 6 View Fig , Table 3). Each radular row contains a rachidian tooth and two half rows of lateral teeth. Examples of radular formulae are presented in Table 3. Half rows of lateral teeth at angle of approximately 50 to 85° with rachidian axis. Rachidian teeth tricuspid: median cusp always present; two lateral cusps, on lateral sides of base of the rachidian tooth, present but small ( Fig. 6A View Fig ). Lateral aspect of base of rachidian teeth straight (neither concave nor convex). Length of rachidian teeth about 20 to 30 µm. Lateral teeth unicuspid with flattened and curved hook. Length of lateral teeth from 35 to 90 µm, gradually increasing towards outer lateral teeth, excluding few innermost and outermost lateral teeth (significantly smaller). Lateral teeth bear outer pointed spine on lateral expansion of base ( Fig. 6F View Fig ). Spine rarely observed because most often hidden below hook of next, outer lateral tooth; spine only observed when teeth not too close or when placed in unusual position; spine absent on outermost lateral teeth.

Esophagus narrow and straight, entering stomach anteriorly. Stomach on left side of visceral mass. Only a portion of stomach seen in dorsal view because partly covered by lobes of digestive gland. Dorsal lobe on right side of visceral mass. Left, lateral lobe ventral. Posterior lobe covers posterior aspect of stomach. Stomach is U-shaped sac divided into four chambers ( Fig. 5D View Fig ). First chamber, distal to esophagus, delimited by thin layer of tissue, receives ducts from dorsal and left lateral lobes of digestive gland. Second chamber delimited by thick, muscular layer of tissue, receives duct from posterior lobe of digestive gland. In third stomach chamber, thick ridges extend towards middle of chamber. Fourth chamber externally similar to third chamber, but characterised by thin internal ridges. Intestine long and narrow, with loops of type II ( Fig. 5E View Fig ), type III ( Fig. 5C View Fig ), or intermediate between types II and III ( Fig. 5F View Fig ). No rectal gland.

Nervous system ( Fig. 5G View Fig ). Circum-esophageal nerve ring post-pharyngeal and pre-esophageal. Cerebral commissure between paired cerebral ganglia short but length varies among individuals. Paired pleural and pedal ganglia all distinct. Visceral commissure short but present and visceral ganglion approximately median. Cerebro-pleural and pleuro-pedal connectives very short and pleural and cerebral ganglia touch each other. Nerves from cerebral ganglia innervate buccal area and ocular tentacles, and penial complex on right side. Nerves from pedal ganglia innervate foot. Nerves from pleural ganglia innervate lateral and dorsal regions of mantle. Nerves from visceral ganglia innervate visceral organs.

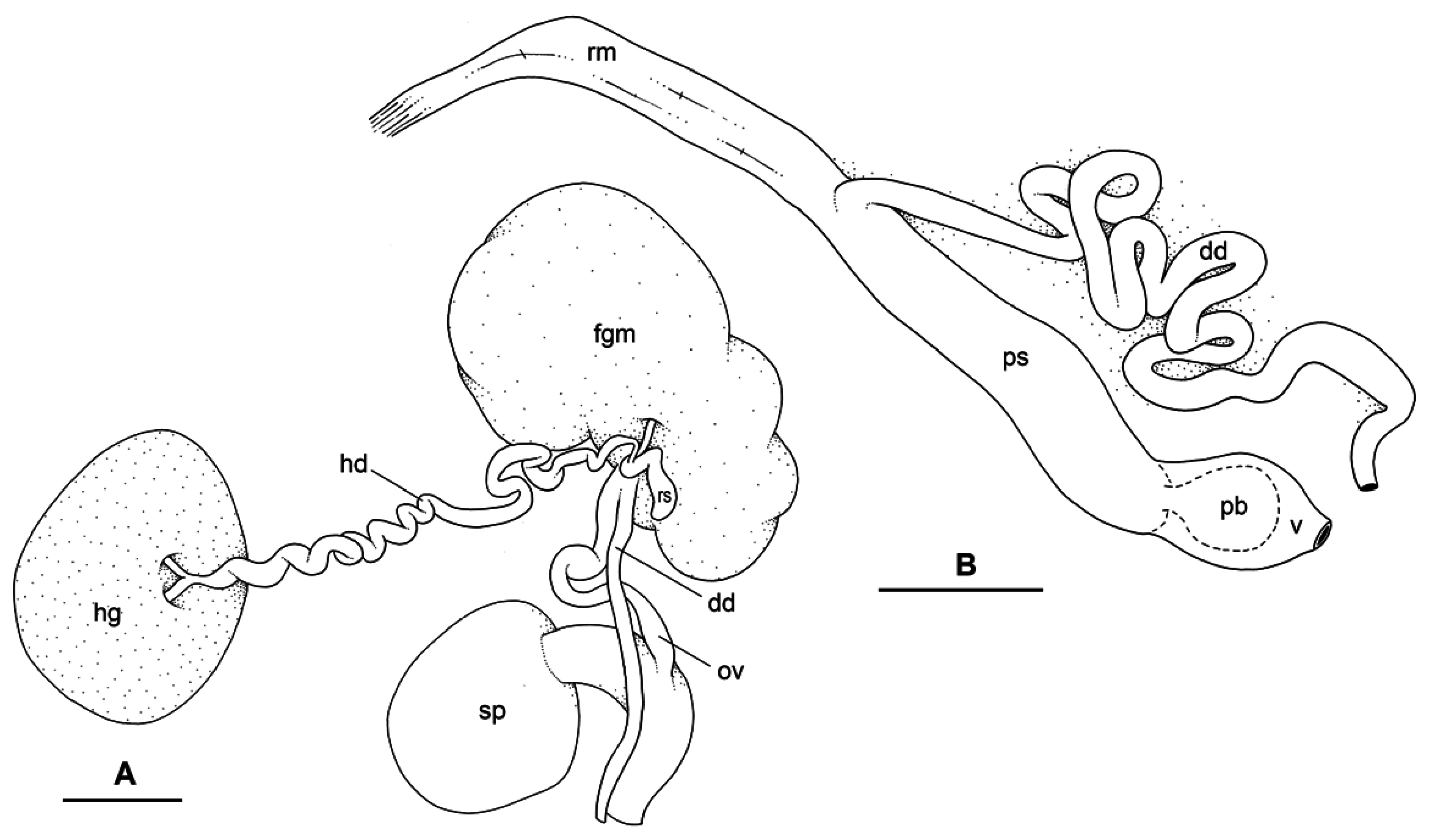

Reproductive system ( Fig. 7A View Fig ). Sexual maturity correlated with body length. Individuals reach reproductive maturity at large size (> 30 mm long). Mature individuals have large, female organs and fully-developed, anterior, male, copulatory parts. Immature individuals (< 30 mm long) may have small, inconspicuous, or simply no female organs. Hermaphroditic gland a single mass. Hermaphroditic duct starts with multiple proximal branches at hermaphroditic gland subsequently merging into single, distal, short duct. Hermaphroditic duct conveys eggs and autosperm from hermaphroditic gland to fertilisation chamber, which connects to large receptaculum seminis. Receptaculum seminis narrow and elongated. Female gland mass contains various glands (mucus and albumen) of which exact connections remain uncertain. Distally, spermoviduct branches into deferent duct (which conveys autosperm to anterior region, running through body wall) and oviduct. Oviduct conveys eggs up to female opening and exosperm from female opening up to fertilisation chamber. Distal region of oviduct (from female opening to duct of spermatheca) short and wide. Spherical spermatheca connects to proximal portion of oviduct through wide, short duct.

Copulatory apparatus ( Fig. 7B View Fig ). Male anterior organs composed of penial complex (penis, vestibule, deferent duct, and retractor muscle). No accessory penial gland. Penial sheath long, approximately half of body cavity length, and thin. Penis delimited by thin tissue touching penial sheath. Penis with proximal stalk and distal bulb-like tip. Both stalk and bulb are soft (not rigid). Penis stalk wide in diameter, between 0.7 mm (immature) and 2.0 mm. Distal region of penial stalk longitudinally folded with one fold. Internally, penis bears thin longitudinal ridges. Bulb-like tip of penis between 1.8 and 2.5 mm long and between 1 and 2 mm wide, often filled with fluid substance which supports flexible structure so that it appears inflated. No penial hooks. Vestibule delimited proximally by attachment of penial sheath to distal end of penis stalk. In mature specimens, retractor muscle cylindrical and thick (between 1 and 2 mm wide); in immature specimens, retractor muscle flattened (about 0.4 mm wide). Retractor muscle inserts near heart on right side of visceral cavity. Retractor muscle marks separation between penial sheath and deferent duct. Deferent duct large and slightly convoluted, but shorter and less convoluted in immature specimens.

Distinctive diagnostic features. Externally, the white band at the margin of the hyponotum is much brighter than in any other onchidiid species. A white margin is occasionally present in a few Platevindex species , but Alionchis jailoloensis lives directly on the surface of soft mud, where Platevindex is not encountered, and Platevindex species can hardly be confused with any other onchidiids (because their body is strikingly flattened and their foot is very narrow). Internally, the bulb-like tip of the penis and the large, cylindrical retractor muscle are unique.

Remarks. One existing onchidiid species name, Onchidium meriakrii Stantschinsky, 1907 , must be transferred to Alionchis . The holotype (34/ 23 mm, SMF 15149), by monotypy, of O. meriakrii shares two diagnostic characters of Alionchis : a median pneumostome at the posterior end of the hyponotum, and large eye tentacles. In addition, the intestinal loops of O. meriakrii are intermediate between type II and type III (see Labbé, 1934: 177, fig. 3, for a comparison of digestive types), as illustrated by Stantschinsky (1907: 360, Fig. A) and confirmed by our examination of the holotype, which is an unusual character known only in Alionchis , one Onchidium species , and two Melayonchis species ( Dayrat et al., 2016, 2017). The type locality of A. meriakrii is in Queensland, Australia, with no more specific information (the type was fixed in formalin more than 100 years ago and no DNA sequencing could be attempted).

The name A. meriakrii is regarded here as a nomen dubium because the anatomy of the male copulatory apparatus, which is critical in distinguishing onchidiid species, is unknown. The penis of A. meriakrii , dissected by Stantschinsky, was not illustrated and is now missing from the holotype. Stantschinsky’s (1907: 374, our translation from German) description of an “anterior part that protrudes into the forecavity” is vague and could apply to the copulatory organs of many onchidiid species. However, Stantschinsky does not describe the actual shape of the penis, nor does he describe whether hooks were present or not. The diameter of the penial sheath and the cylindrical retractor muscle are similar in A. jailoloensis and A. meriakrii , but these structures are frequently similar between related species. Also, Stantschinsky does not mention the live colour of A. meriakrii because he did not collect the animals himself. So, it is unknown whether the margin of the hyponotum of A. meriakrii is white, as in A. jailoloensis , or if any other external colour trait might distinguish it from A. jailoloensis . The holotype of O. meriakrii is part of an Alionchis species. However, it cannot be determined at this stage whether it is part of the same species as the Halmahera populations described here as A. jailoloensis . Our team has spent four weeks exploring mangroves of the eastern coast of Queensland, collecting gastropods from 29 stations from 16° to 21° S. Unfortunately, we did not find any Alionchis there. If one single species of Alionchis was broadly distributed from Halmahera to Queensland, we could have found it at other localities in between, but we did not find any Alionchis in Ambon, Seram, the Kei Islands, or in Northern Territory ( Australia). Also, no Alionchis was found in the collections made during recent expeditions in Papua New Guinea ( Madang and Kavieng) led by Philippe Bouchet for the Museum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris.

Naturally, we may have missed Alionchis in Queensland and everywhere else between Queensland and Halmahera. Or, it could be that A. meriakrii is restricted to the more northern latitudes in Queensland (north of Cairns), close to the Torres Strait. It is also possible (though less likely) that there are two allopatric species of Alionchis , one in eastern Indonesia and one in southern Queensland (south of Mackay), with no species in between. If Alionchis slugs are ever found in Queensland, it will be necessary to compare their DNA sequences to A. jailoloensis , because onchidiid species can be morphologically cryptic.

Stantschinsky (1907) described three species of onchidiids from Queensland, only one of which ( Onchidium buetschlii Stantschinsky, 1907 ) was found during our exploration of the mangroves of Queensland (Goulding et al., in press-a). It is surprising that we could not find the two other species described by Stantschinsky from Queensland ( O. meriakrii Stantschinsky, 1907 and O. fungiforme Stantschinsky, 1907 ) despite wide and intense sampling in Queensland, as we have been able to locate most other existing onchidiid species by returning to type localities. Also, most early descriptions of onchidiid species were based on fairly common species (people were not traveling deep into mangrove forests to find them) and so it is strange that one of the few specimens sent to Stantschinsky from Queensland was an Alionchis (which, based on our experience, are extremely rare slugs) and that we did not find any even though we collected hundreds of onchidiid slugs there. This leads us to wonder whether the localities of Stantschinsky’s specimens may have possibly been mixed up. In the same paper, Stantschinsky (1907) described an onchidiid species from Mindanao, Philippines, which is just north of Halmahera, and maybe the holotype of O. meriakrii was from Mindanao and not Queensland. Unfortunately, that is something that we will never know, even if Queensland mangroves were to be explored in much greater depth.

At any rate, because of all the issues mentioned above, we consider that, for now, A. jailoloensis is endemic to Halmahera and that A. meriakrii is a name of doubtful application.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.