Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1206/00030090-417.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E587EC-FFBB-FFA1-749D-FCB58161F916 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| status |

|

Dasypus novemcinctus Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL

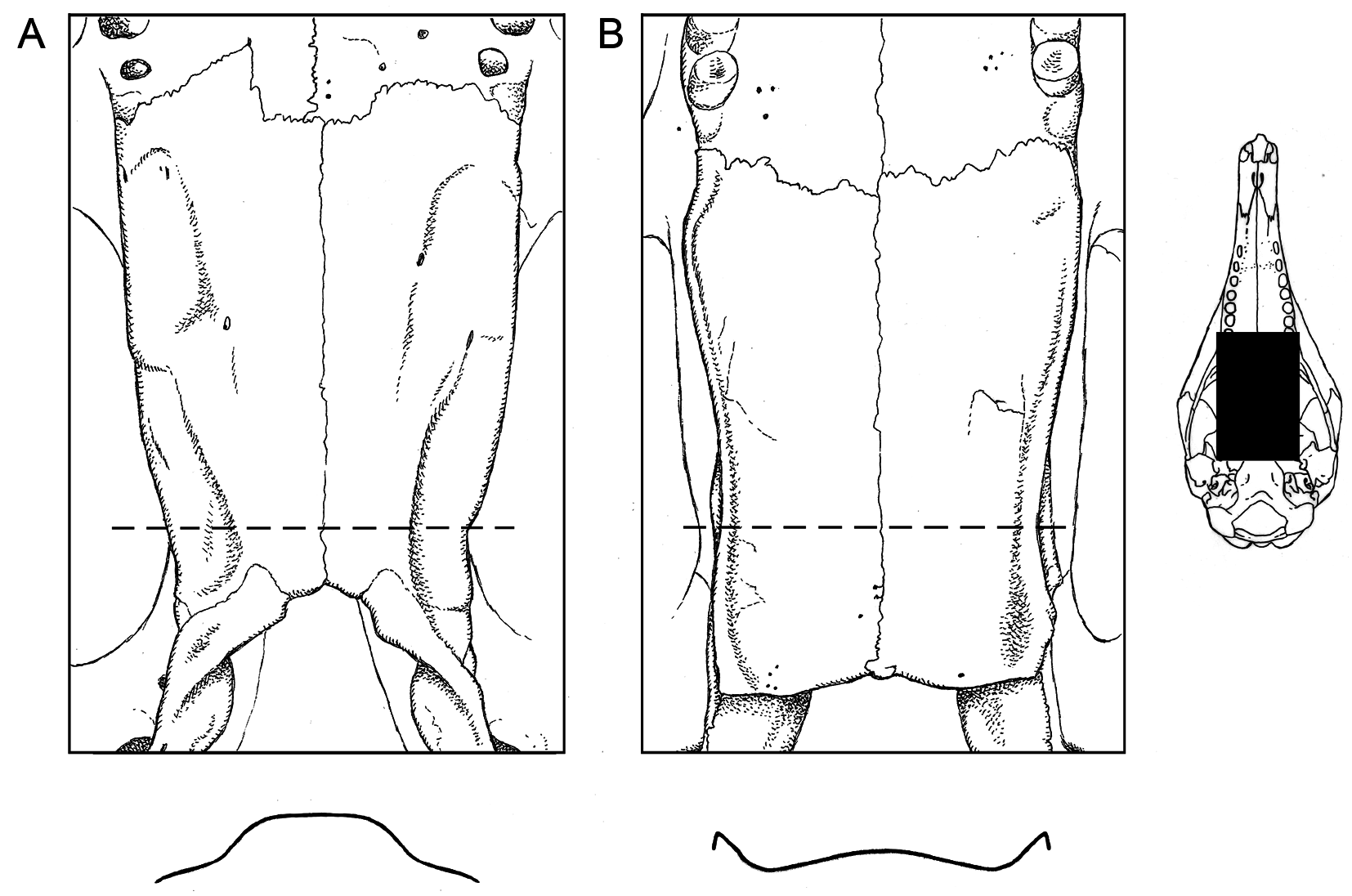

Figures 3A View FIG , 4A View FIG

VOUCHER MATERIAL (TOTAL = 6): Nuevo San Juan (AMNH 268229, 268230, 268231; MUSM 11088, 11089, 11090).

OTHER INTERFLUVIAL RECORDS: Actiamë ( Amanzo, 2006), Itia Tëbu ( Amanzo, 2006), Jenaro Herrera (Pavlinov, 1994), Río Yavarí (Salovaara et al., 2003), Río Yavarí-Mirím (Salovaara et al., 2003), San Pedro (Valqui, 1999).

IDENTIFICATION: Our voucher material conforms to the qualitative descriptions of Dasypus novemcinctus provided by Wetzel and Mondolfi (1979) and Wetzel (1985b). Additionally, measurements of our voucher material ( table 3 View TABLE 3 ) fall within the observed range of variation among Amazonian specimens of D. novemcinctus tabulated by Wetzel and Mondolfi (1979: table 1). Our single preserved skin (MUSM 11088) has eight moveable bands, of which the fourth has 56 scutes; both counts are well within the range of meristic variation for the species (Wetzel and Mondolfi, 1979).

Wetzel et al. (2008) recognized several subspecies of Dasypus novemcinctus but provided no phenotypic criteria for distinguishing them. In the absence of any critical revision of this implausibly widespread taxon (which ranges from the southern United States to Uruguay), it seems pointless to use trinomial nomenclature or to speculate about the validity of any nominal forms currently treated as subspecies or synonyms. However, it is noteworthy that (1) Amazonian specimens seem to be substantially larger than specimens from other South American landscapes (e.g., the Brazilian highlands and northern Venezuela; Wetzel and Mondolfi, 1979: table 1), (2) sequence variation at the mitochondrial ND1 locus among specimens identified as D. novemcinctus appears to be highly structured geographically (Loughry and McDonough, 2013: fig. 7.2), and (3) phylogenetic analyses of mitogenomes do not recover D. novemcinctus as a monophyletic taxon ( Gibb et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2016). Unfortunately, western Amazonian populations of D. novemcinctus are not represented in any published molecular analysis.

Dasypus novemcinctus is easily distinguished from its sympatric congener D. pastasae by its smaller adult size (typically < 6 kg, versus> 8 kg in D. pastasae ); by lacking a vestigial fifth digit on the forefoot (a tiny fifth digit is almost always present in D. pastasae ); by the absence of enlarged, spurlike scales on the knee (present in D. pastasae ); and by having rounded lateral palatine margins (fig. 4A).

ETHNOBIOLOGY: The only general name for the nine-banded long-nosed armadillo is sedudi (an unanalyzable term with no other meaning), a word that is not found in other Panoan languages and which has no archaic or ceremonial synonyms. Three subtypes of the nine-banded longnosed armadillo are recognized by Matses hunters: sedudimpi (“small nine-banded long-nosed armadillo”), sedudidapa (“large nine-banded longnosed armadillo”), and akte tsawes (“water/ stream/river armadillo”). It is notable that the term for the third subtype contains the term tsawes, which is also the name for the great longnosed armadillo ( D. pastasae ), but in this case the term tsawes can be interpreted as a general term for “armadillo” (the Matses are steadfast in their classification of this variety as a type of sedudi). In addition to being smaller, sedudimpi is said differ from the other varieties by having a darker back, a grayish yellow underside, and a tail with stripes along the edges of the bands. Sedudidapa, in addition to being larger, is said to be lighter in color than other varieties. Akte tsawes is said to be characterized by living in or adjacent to floodplain forest along large streams and rivers.

The only economic importance of ninebanded long-nosed armadillos for the Matses is as food, but unlike the greater long-nosed armadillo it is not a preferred game species and, due to the dietary taboo limiting its consumption to old people, it is not frequently hunted.

When a nine-banded long-nosed armadillo is encountered in a burrow it may be flooded out in the same manner as described below for the great long-nosed armadillo, but this species often nests on the surface under piled-up leaves, typically in floodplain forest and on levee islands. A hunter may come upon armadillo spoor and follow it, or he may simply happen upon such a leaf nest. When he finds the leaf nest, he lightly introduces a palm frond into the entrance of the nest to see if it is inhabited. If the armadillo growls, he cuts saplings into stakes and makes a circular fence around the nest. Then he enters the circle, takes apart the nest, and kills the trapped armadillo with a machete.

Now that the Matses have flashlights, they hunt at night by walking along forest paths. The primary motivation for night-hunting is to kill pacas, which are common in secondary forest near villages, especially when peach palm ( Bactris gasipaes ) fruits are ripe (from January to March), but nine-banded long-tailed armadillos also frequent secondary forest and are sometimes shot if encountered on a night hunt.

Young people do not eat the nine-banded longnosed armadillo lest they become weak and thin or begin to eat clay. This armadillo is also believed to make children ill, causing a high fever. Therefore, it is primarily eaten by the elderly.

MATSES NATURAL HISTORY: The nine-banded long-nosed armadillo is similar to the greater long-nosed armadillo, but it is smaller, has a thinner tail and head, has a bump on its head, has a yellower underside, narrower bands on its carapace, and a stronger and fouler smell. Both species have a “branched” penis.

Nine-banded long-nosed armadillos are found in upland forest, in the floodplains of large streams and rivers, and in both primary and secondary forest. They are frequently found in abandoned swiddens and old blowdowns. They are also common in fresh blowdowns and on levee islands along rivers. (Thus, nine-banded long-nosed armadillos use a wider range of habitats than greater long-nosed armadillos.) They are common and, unlike greater long-nosed armadillos, do not tend to get hunted out (at least in part because they are not a preferred game species).

Nine-banded long-nosed armadillos make their nests in underground burrows, on the surface under leaf piles, and inside hollow logs. Burrows are especially common in blowdowns. These armadillos have more than one nest and typically sleep in a different one each night. Burrows may be on hilltops or hillsides, in floodplain forest, or in secondary forest, but not in stream headwater gullies (the preferred site of great long-nosed armadillo burrows). The typical burrow entrance is angled straight down. If the burrow is in floodplain forest or on a levee island it goes straight down for about 30 cm and then becomes horizontal and extends only a short distance (in which case the armadillo can be easily dug out). If the burrow is in a hillside in upland forest, it will become horizontal for a short distance and then angle upward (in which case it cannot be flooded out). The burrows have a bed made of dead leaves. Nests in hollow logs also have a leaf bed. Leaf-pile nests are usually made next to a log or a buttress root. The leaf litter is piled very high and the armadillo sleeps under the leaves, not on them. Leaf-pile nests are made in floodplain forest.

The nine-banded long-nosed armadillo is nocturnal. It forages all night long. It has clear and wide paths that it follows as it forages. It leaves its path to root for earthworms at the base of hills and other places. Sometimes it returns to the same place to forage, and at other times it does not. It follows streams, rooting in the soft soil for earthworms. It roots in places that are close to each other, leaving areas clear of leaf litter where it roots. It makes a lot of noise as it travels quickly along its path, with its tail up in the air. It runs very quickly along its path to escape from humans, smacking its tail on the ground as it runs. Where there is no path it cannot run as quickly, having to jump over or go around obstacles. It can be grabbed when it is not on its path. Armadillos are safer from predation when they are on their paths, but they must leave their paths to forage. (One could infer the same for greater long-nosed armadillos, but because those are more rarely encountered at night, Matses informants did not comment on this.)

Nine-banded long-nosed armadillos are solitary. The female gives birth to two or three offspring. Larger females give birth to three. The young follow the mother when they are little.

White flies (small biting flies that look like light-colored mosquitoes; probably phlebotomine psychodids) live with and follow ninebanded long-nosed armadillos. Jaguars, pumas, bush dogs, and caimans eat nine-banded longnosed armadillos.

They make a low grunting growl when disturbed.

Nine-banded long-nosed armadillos dig into rotten logs to eat armored millipedes ( Barydesmus spp. [ Platyrhacidae ]) and other invertebrates. They root in the ground to eat earthworms and grubs that live in the ground. They also eat mole crickets and other insects. They eat the mesocarp of isan palms ( Oenocarpus bataua [ Arecaceae ]), kuëbun isan palms ( O. mapora ) and swamp palms ( Mauritia flexuosa [ Arecaceae ]). They also eat some dicot tree fruits and the seeds of tonnad trees (an unidentified species of Myristicaceae ). They eat maggots that they find in rotten meat, but do not eat the meat itself.

REMARKS: The nine-banded long-nosed armadillo has been the subject of numerous field studies at temperate latitudes, especially as an invasive species in the United States, but little has been published about its ecology or habits in tropical rainforest. Information about this species (or species complex; see above) obtained from Matses interviews is notable for observations about several behaviors not or seldom mentioned in the literature, including use of well-worn pathways (mentioned only by Neck [1976] and Emmons [1997] among the references we consulted), tail-slapping when pursued by predators, the use of surface nests rather than burrows as diurnal refugia in floodplain habitats (Layne and Waggener, 1984; Platt and Rainwater, 2003), and frugivory ( Emmons, 1997). Also of interest is the alleged association of this species with small biting flies (? Brumptomyia spp. [ Psychodidae ]; Lainson et al., 1979), and observations about predators ( Dasypus novemcinctus leads an almost predation-free existence in the partially defaunated habitats of temperate North America; Loughry and McDonough, 2013). By contrast, Matses observations about litter size are anomalous. Whereas the Matses report litters of only two to three offspring in this species, 95% of D. novemcinctus litters in North America consist of genetically identical quadruplets (Newman, 1913; Prodöhl et al., 1996), and similar observations have been reported from South America (e.g., Noss et al., 2003: table 3 View TABLE 3 ). Although we could offer several ad hoc explanations for this discrepancy, none are supported by actual evidence, so we cannot discount the probability that the Matses are simply wrong.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.