Parorectis Spaeth, 1901

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.4565396 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7D969F82-40F2-4825-A6D8-0131E48BB1EC |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4588700 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D5A115-D81F-FF8E-A7E8-225F98958E72 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Parorectis Spaeth, 1901 |

| status |

|

Parorectis Spaeth, 1901 View in CoL

Type species: Cassida rugosa Boheman, 1854 , original designation, [not Lederer ( Insecta View in CoL : Lepidoptera View in CoL )].

Parorectis Spaeth 1901: 346 View in CoL (as subgenus of Orectis ).

Type species: Cassida callosa Boheman, 1854 , original designation.

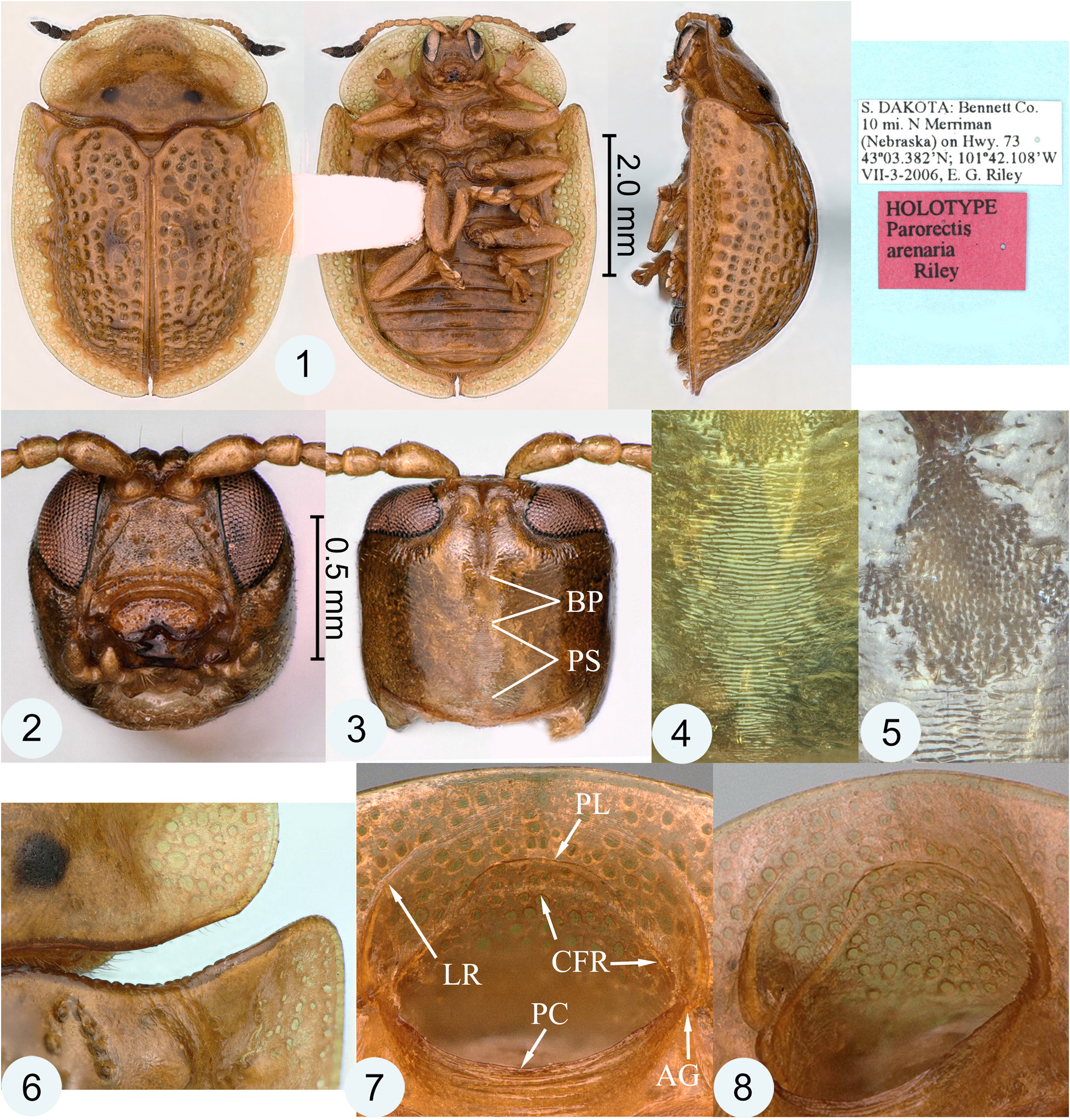

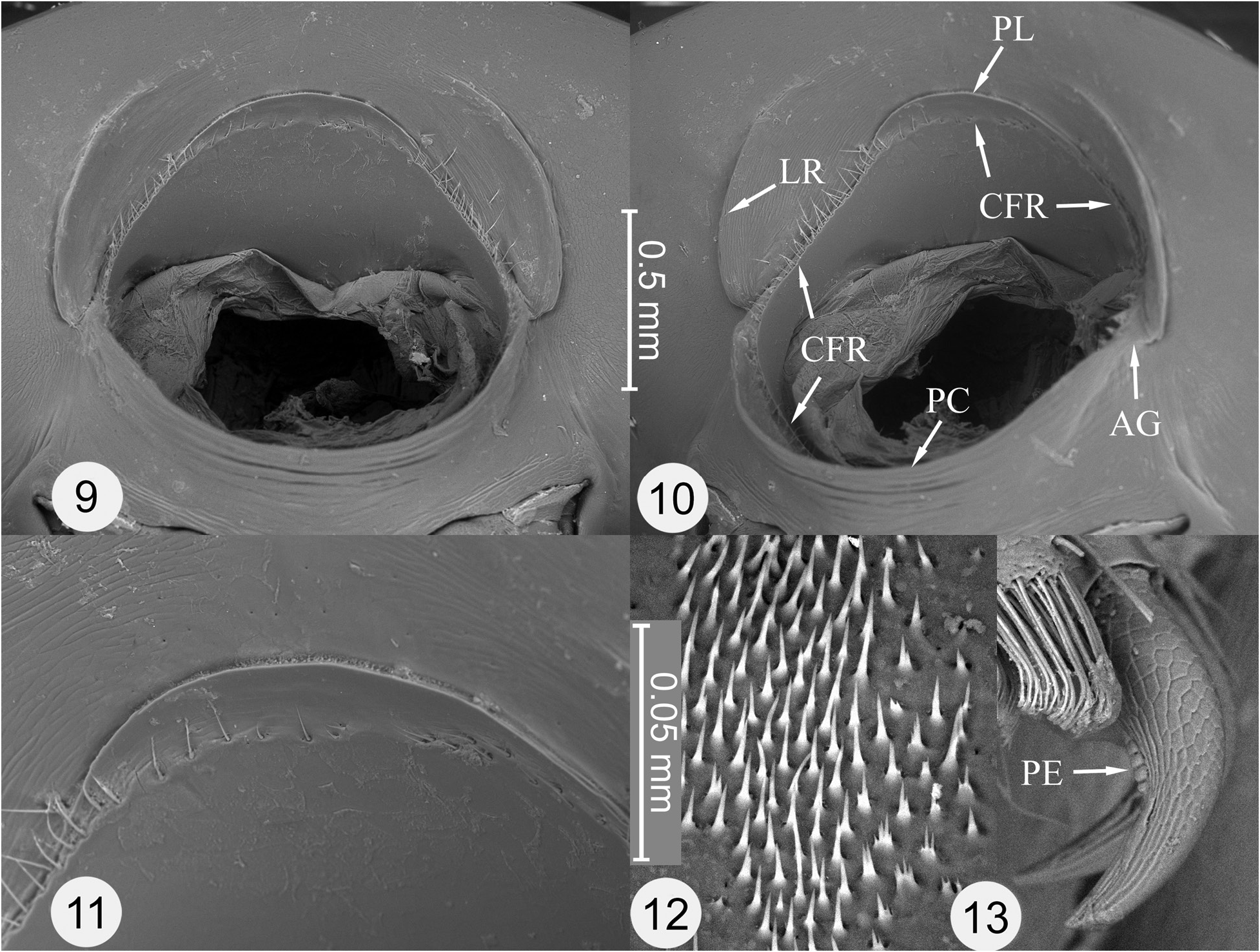

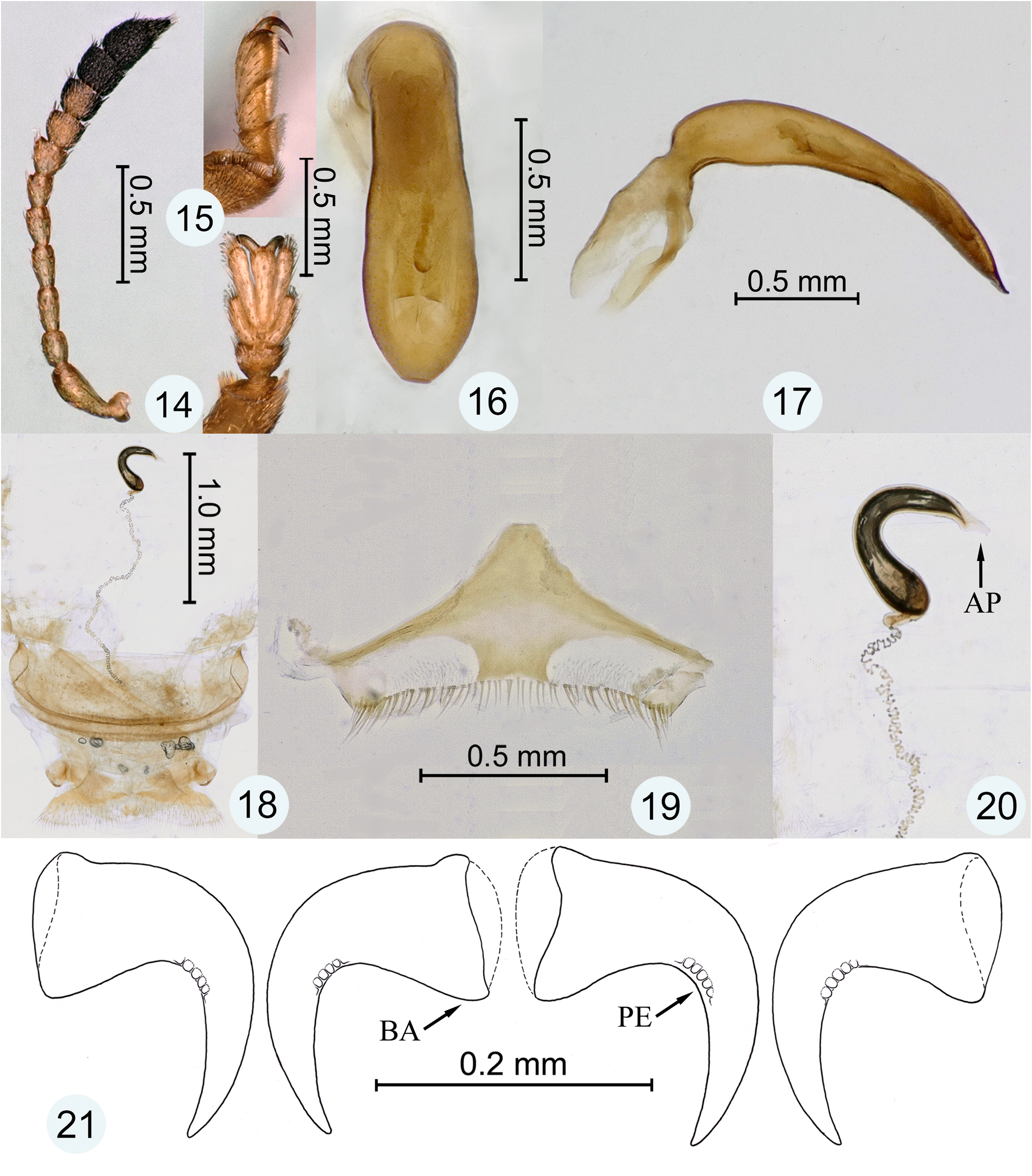

Generic diagnosis. The following combination of characters will distinguish the genus Parorectis among the New World genera of the tribe Cassidini : Prothorax with circum-foraminal ridge forming inner margin of antennal groove for reception of antennomeres 2–3 ( Fig. 7–10 View Figures 1–8 View Figures 9–13 : CFR); pleuron lateral to circum-foraminal ridge with elevated lateral ridge forming outer margin of antennal groove for reception of antennomers 2–3 ( Fig. 7–10 View Figures 1–8 View Figures 9–13 : LR). Elytron with anterior margin distinctly crenulate ( Fig. 6 View Figures 1–8 ), disc tuberculate or strongly punctate. Pro-, meso- and metatarsal claw-pairs symmetrical in both sexes; each claw simple (without basal tooth), with basal angle rounded ( Fig. 21 View Figures 14–21 : BA); pectens present ( Fig. 13 View Figures 9–13 , 21 View Figures 14–21 : PE), inconspicuous (micropectens) and symmetrical (equally developed on respective internal and external surfaces of each claw, as in Fig. 21 View Figures 14–21 ). Claw segment (tarsomere IV) with lateral flanks not projected below claws.

Systematic position. Riley (1986) classified Parorectis with the other North American genera that possess crenulate anterior elytral margins, all claw-pairs symmetrical in both sexes, and pectens, when present, symmetrical.

Antennal grooves and circum-foraminal ridge. Parorectis has been reported to possess antennal grooves ( Borowiec and Świętojańska 2018 [in key]; López-Pérez and Zaragosa-Caballero 2018 [in key]; Riley 1986 [in key]; Riley et al. 2002 [in key]). This is a reference to what superficially appears to be a discontinuity or break in an anterior extension of the ridge forming the edge of the prosternal collar. The genera Deloyala Chevrolat and Chiridopsis Spaeth have similar apparent discontinuities accompanied by a groove-like channel at this position. This channel is wider and more strongly developed in these genera than in Parorectis . It is likely that living adults of all three genera are capable of flexing their antennae backward, seating the narrowest antennomeres (III and IV) in this channel or break. Among preserved specimens of Parorectis , only the occasional individual will have an antenna in this position.

In Parorectis , the circum-foraminal ridge is continuous and encircles the entire anterior prothoracic foramen, but almost all of it can only be viewed after removal of the head ( Fig. 7–10 View Figures 1–8 View Figures 9–13 : CFR). Scanning electron microscopy reveals that the true circum-foraminal ridge is accompanied by a fine line of setae ( Fig. 9–11 View Figures 9–13 : CFR). The apparent discontinuity is not a break in the circum-foraminal ridge, but the result of a separate structure, a lateral ridge located laterad on the thoracic pleuron ( Fig. 7–10 View Figures 1–8 View Figures 9–13 : LR). The lateral ridges begin at the apparent break on each side of the anterior foramen, arch forward and ultimately dissipate anteriorly. They could easily be mistaken for part of the circum-foraminal ridge if the head were not removed. The origin of the lateral ridge, either an entirely novel structure or a detached and off-set anterior extension of the prosternal collar, is undetermined at this time. At the point of the apparent break, the anterior portions of the true circum-foraminal ridge extend upward on each side onto the ceiling of the foramen and arch forward to meet anteriorly. Basally, the circumforaminal ridge is located internal to the edge of the prosternal collar ( Fig. 10 View Figures 9–13 : CFR). At its distal and uppermost point, the ridge is augmented by a smooth crescent-shaped, platform-like structure ( Fig. 7–11 View Figures 1–8 View Figures 9–13 : PL). This structure likely serves as the plectrum (scraper) of the stridulatory mechanism and possibly engages with the cephalic binding patch (see below).

Stridulation mechanism. A vertico-pronotal type of stridulatory device is said to be widespread among taxa of the Cassidinae , including the former Hispinae ( Schmitt 1991, 1994). This type of stridulatory mechanism consists of a presumed plectrum (scraper) located on the thorax and a pars stridens (file) located on the posterodorsum of the cranium. López-Pérez et al. (2018: table S1) recorded a stridulatory file in the male sex of 33 genera of Cassidini (this tribe including the Aspidimorphini and Ischyrosonychini ). In Parorectis , the platform-like crescent-shaped structure likely functions as the plectrum ( Fig. 7–11 View Figures 1–8 View Figures 9–13 : PL). Other than the circum-foraminal ridge, which is weakly developed at this position, there are no other structures on the ceiling of the anterior foramen that could serve as a plectrum. The pars stridens consists of an elongate patch of very fine transverse ridges that is tapered at both ends ( Fig. 3, 4 View Figures 1–8 : PS). While the plectrum portion of the mechanism is present in both sexes in Parorectis , the pars stridens is only present in males; the corresponding location on the cranium is smooth in females.

The sexual dimorphism of the pars stridens, present in males and absent in females, raises the interesting question: what function does stridulation serve these beetles? It is unlikely that defense is the primary function of stridulation, although it could be a secondary function in males. More likely, the function of stridulation is somehow sexual in nature, probably involving male-to-male competition or male-to-female courtship behavior.

Cephalic binding patch. At the center of the cranial dorsal surface of Parorectis species is a dense patch of spicules located just anterior to the position occupied by the pars stridens. An inexperienced observer using normal light microscopy could easily mistake the reflectivity of this patch for a pars stridens. The individual spicules of the patch are short, pointed or multi-pointed, inclined forward, and their arrangement is confused ( Fig. 5 View Figures 1–8 , 12 View Figures 9–13 ). It is probable that head-to-thorax binding is the function of this patch; thus, the term cephalic binding patch is proposed here. This binding mechanism, however, is different from that of the better-known elytron-to-body binding patches where there are interdigitating patches on corresponding body parts ( Samuelson 1996). In Parorectis , there are no corresponding spicules on the ceiling of the anterior prothoracic foramen. The spicules of the cephalic binding patch likely engage with the thoracic surface including the structure here called the plectrum. In Parorectis , both males and females possess equally developed cephalic binding patches, and both sexes have a “plectrum” suggesting that the two structures function in head-to-thorax binding. Head-to-thorax binding, where the head can be withdrawn and locked in a safe position within the prothorax, is likely part of a broad suite of defensive behaviors in adult tortoise beetles.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Cassidinae |

|

Tribe |

Cassidini |

Parorectis Spaeth, 1901

| Riley, Edward G. 2020 |

Orectis

| Spaeth F. 1901: 346 |

Parorectis

| Spaeth F. 1901: 346 |