Parapontophilus occidentalis ( Faxon, 1893 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4007.3.4 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:63C0147F-0B9E-44EC-874D-13227EB0961E |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5616715 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03C2C649-C276-654B-FF00-2B63EAE3C32F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Parapontophilus occidentalis ( Faxon, 1893 ) |

| status |

|

Parapontophilus occidentalis ( Faxon, 1893) View in CoL

Figures 2–4 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4

Pontophilus occidentalis Faxon, 1893: 200 View in CoL . Hendrickx 1993: 306 (Lista 3); 1995 FAO: 439 (key), Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 , 439 (list). Pontophilus gracilis occidentalis View in CoL .— Kameya et al. 1997: 92 (list). Wicksten & Hendrickx 2003: 69 (list).

Parapontophilus occidentalis View in CoL .— Retamal & Jara 2002: 204 (list). Komai 2008: 287, figs. 8, 20D (synonymy). De Grave & Fransen 2011: 461 (list). Hendrickx 2012a: 293, Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 d, 315 ( Table 1); 2012b: 329, Figure 5 A. Moscoso 2012: 60. Pontophylus gracilis occidentalis View in CoL .— Guzmán & Quiroga 2005: 288.

Material examined. A total of 136 specimens was collected from 11 localities sampled during the TALUD XV, XVI and XVI-B cruises.

TALUD XV. St. 9 (24º 35' 12" N; 112º 52' 48" W), 2 F (CL 11.1–13.1 mm) and 1 ovig. F (CL 12.9 mm), July 30, 2012, BS, 1425–1494 m (EMU–10534).

TALUD XVI, St. 3 (28º 39' N; 115º 49' W), 1 F (CL 11.0 mm), July 31, 2013, BS, 1397–1408 m (EMU– 10512).

TALUD XVI-B, St. 1 (28º 27' 24" N; 115º 48' 55" W), 6 M (CL 11.0– 13.2 mm) and 2 F (CL 9.5–16.1 mm), May 23, 2014, BS, 2038–2054 m (EMU–10502). St. 3 (28º 41' 17" N; 115º 50 '4" W), May 23, 2014, 1F (CL 13.7 mm), BS, 1350–1365 m (EMU–10503–A). St. 8 (29º 23' 5" N; 115 45' 1" W), 9F (CL 8.7–13.0 mm), May 31, 2014, BS, 1416–1480 m (EMU–10504). St. 9 (29º 20' 53" N; 115º 51' W), 11 M (CL 10.0– 13.3 mm), 11 F (CL 8.4– 16.1 mm), and 11 ovig. F (CL 10.2–14.9 mm), May 31, 2014, BS, 1848–1860 m (EMU–10505). St. 15 (29º 40' 2" N; 116º 6' W), 1 M (CL 9.7 mm), 2F (CL 12.1–12.4 mm), and 1 ovig. F (CL 12.0 mm), May 30, 2014, BS, 2010– 2046 m (EMU–10503–B). St. 16 (29º 51' 2" N; 116º 9' W), 2M (8.8–10.3 mm), 10 F (CL 9.0– 13.3 mm), and 9 ovig. F (10.7–12.7 mm), May 29, 2014, BS, 1360–1425 m (EMU–10506). St. 20 (30º 51' 17" N; 116º 42' 11" W), May 26, 2014, BS, 2075–2090 m, 3 F (CL 8.9–13.3 mm) and 4 ovig. F (CL 12.5–15.6 mm) (EMU–10507), and 5 M (10.6–11.5 mm) and 18 F (CL 8.8–14.5 mm) (EMU-10533). St. 21 (30º 49' 2" N; 116º 47' 5" W), 3 M (CL 10.0– 11.9 mm), 15 F (CL 10.6–13.9 mm), and 3 ovig. F (CL 13.1–13.9 mm), May 28, 2014, BS, 2018–2093 m (EMU– 10508). St. 23 (30º 56' 2" N; 116º 40' 55" W), 1M (CL 10.5 mm), 2 F (CL 9.3–10.3 mm), and 2 ovig. F (CL 11.0– 12.2 mm), May 28, 2014, BS, 1296–1340 m (EMU–10509).

Additional material. Material cited by Hendrickx (2012b) collected in four localities, including 2 males, 10 females, and 4 ovigerous females ( Table 1).

Morphologic aspects. Taxonomic remarks. Based on the presence or absence of cardiac and epibranchial teeth, Chace (1984) and Komai (2008) recognised two informal groups of species within the genus Parapontophilu s. Parapontophilus occidentalis features both teeth, thus showing its close affinity to the first group of 11 species (the " P. gracilis " group). The material examined shares basic characteristics with the syntype illustrated by Komai (2008: Figure 8 View FIGURE 8 ), including the size and relative position of dorsal and lateral carapace teeth, the short rostrum (not overreaching the cornea distal margin) provided with two pairs of short, lateral teeth, the very deep carapace with a sharp ventral flap ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 ), and a relatively short sixth abdominal somite. The typical sexual dimorphism observed in the antennula of males of Parapontophilus and other crangonids (i.e., lateral flagellum stouter and longer than in females; see Komai 2008 and Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 A herein) is also accompanied by a strong reduction of the second segment in males (almost squarish) ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 A) compared to females, in which it is almost twice as long as wide ( Figure 2 View FIGURE 2 C). Difference in proportion of the second antennular segment between male and female has apparently not been emphasized previously, although it can be observed in Komai (2008) anterior carapace figures of P. cornutus Komai, 2008 .

Cruise Station Date Depth Sex (Size) Catalogue TALUD VII St. 34B Jun 9, 2001 1500–1520 m 1 F (CL 5.5 mm) EMU-8210-A 1 F (CL 8.2 mm) EMU-8210-C TALUD VIII St. 3 Apr 16, 2005 1100 m 2 F (CL 8.5–12.2 mm); 2 EMU-8151

ovig. F (11.3–11.8 mm)

1 M (CL 11.4 mm) EMU-8210-B TALUD X St. 22 Feb 13, 2007 1575–1586 m 1 ovig. F (14.6 mm) EMU-8098 6 F (CL 8.2–12.8 mm); 1 EMU-8153 ovig. F (11.9 mm)

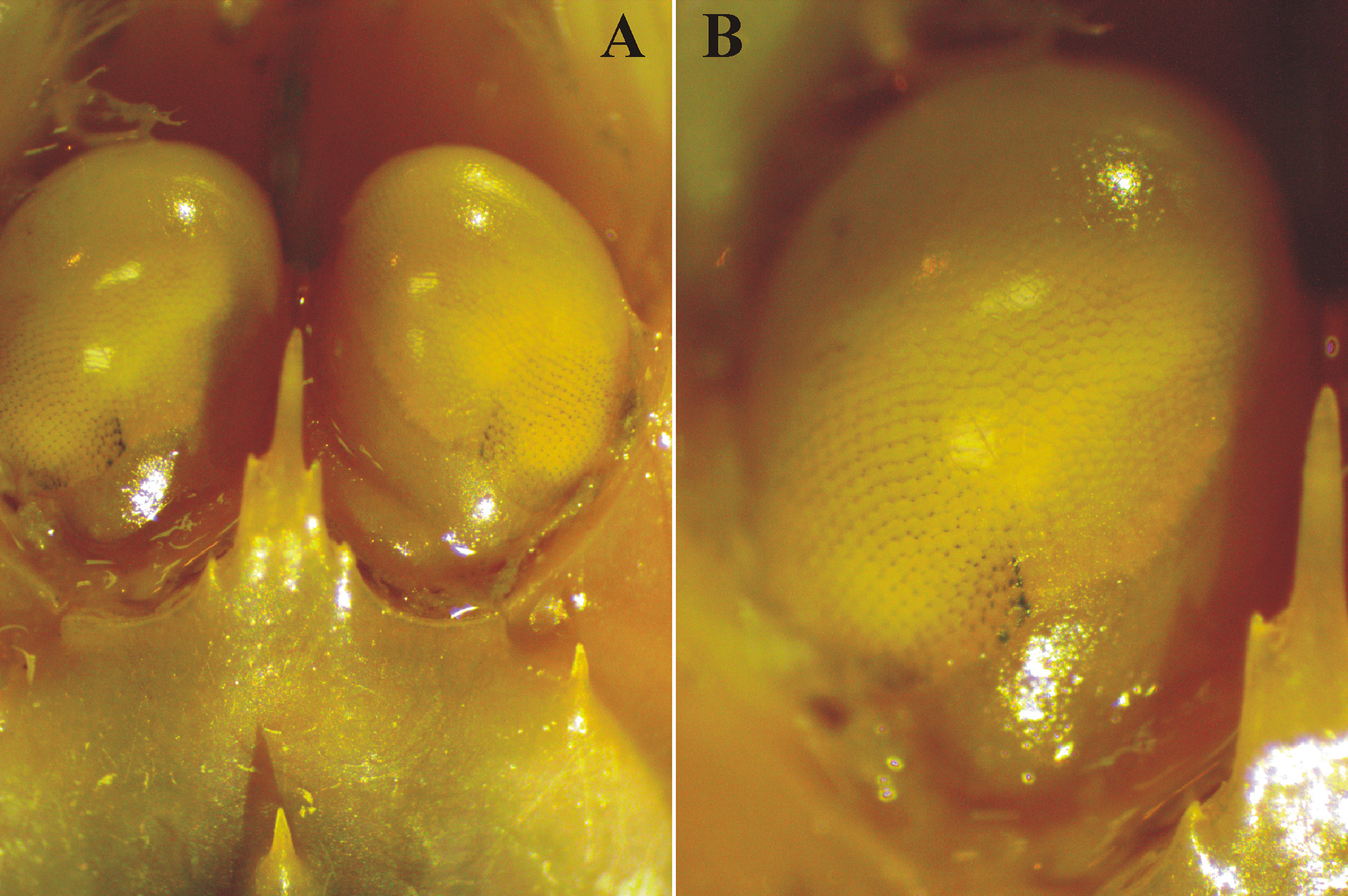

TALUD X St. 25 Feb 14, 2007 837–840 m 1 M (CL 12.1 mm) EMU-8210-D Vision. The deep-water shrimp P. occidentalis was not considered by Schiff & Hendrickx (1997) in their review of eye structure of shallow and deep-water decapod crustaceans from the Mexican Pacific. Komai (2008: Figure 20D) presented a dorsal photograph of the eyes of one of the P. occidentalis syntypes. The whitish, nonfaceted cornea of the eye of this syntype material is in contrast with the series of specimens examined during this study in which distinctly delineated facets were observed in the cornea, more clearly on the proximodorsal part of the eye ( Figure 3 View FIGURE 3 ). When comparing specimens from different depths (837 to 2090 m), no differences were observed and all the eyes featured the same aspect, with facets well delimited dorsally and fading away in the front. However, there was no sign of pigmentation, indicating a well-advanced but incomplete degeneration process of the cornea.

Color. Fresh specimen. Body light brown to pinkish, flush of darker brown on anterior part of carapace, uropods and distal part of chelae, tip of fingers of chelae whitish. Eye bright orange to yellowish ( Figure 4 View FIGURE 4 ). Color of freshly caught specimen described herein differs somewhat from the color provided by Faxon (1895: Pl. D, 2) which is salmon in the abdomen and appendages, and brownish on the cephalothorax.

Biological and ecological aspects. Geographic distribution. The species is known from California to northern Chile. Distribution in Mexico includes the east part of the central Gulf of California ( Hendrickx 2012b) and the west coast off the Baja California Peninsula (material examined), essentially its northern half ( Figure 1 View FIGURE 1 b). As noted previously, due to the lack of intensive sampling program in the region, records for deep-water crangonids in the eastern Pacific were very scarce until recently (see Hendrickx 2011; 2012b; 2014; Hendrickx & Ayón-Parente 2012) and there are no records for P. occidentalis in the GBIF data base ( GBIF 2014). In addition to the localities included in the original description by Faxon (1893), it was reported from northern Peru (1850–2100 m) and northern Chile (1910–2120 m) by Zarenkov (1976) and is also known from California ( Wicksten 1977) and southern Peru ( Moscoso 2012; 15º 45' S, 3475 m). It was not collected during the "Miguel Oliver" cruise (2008) off Ecuador (depth range of the survey, 500–1500 m) ( Cornejo-Antepara 2010), neither was it reported by Lopez (2011) during the same cruise from off El Salvador to Panama (overall depth range, 108–1530 m). Komai (2008) included four localities for P. occidentalis : off Guatemala, Costa Rica, Panama, and Chile, without further details.

In Mexico, Hendrickx (2012b) reported 16 specimens of P. occidentalis from four stations in the central and southern Gulf of California ( Table 1), within a depth range from 837 to 1586 m. This species was not found during another survey off the SW coast of Mexico (Jalisco to Guerrero: TALUD XII, 20 trawls, from 296 to 2136 m) (see Hendrickx 2012a for further details), although the total number of deep-water trawls and the depth range sampled were similar to those of surveys performed off the west coast of the Baja California Peninsula (this study) and in the Gulf of California.

Bathymetric distribution. Taking into account that most (98%) specimens were collected from the northern half of the Baja California Peninsula (BCP) and that only three specimens were collected in its southern half, ecological aspects were studied considering only the material collected off the northern part of the BCP (surveys TALUD XVI and XVI-B). Parapontophilus occidentalis was collected between 1296 and 2093 m and was mainly distributed between 1700 and 2100 m (Figure 5), where it was collected in 100% of the samplings ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ). Some organisms were distributed between 1300 and 1500 m, with a gap on the presence of P. occidentalis between 1500 and 1700 m. It is uncertain whether the lack of organisms at the 1500–1700 m depth range is attributable to the influence of some unknown environmental factor or to a low sampling intensity ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ). Density and biomass showed similar bathymetric patterns.

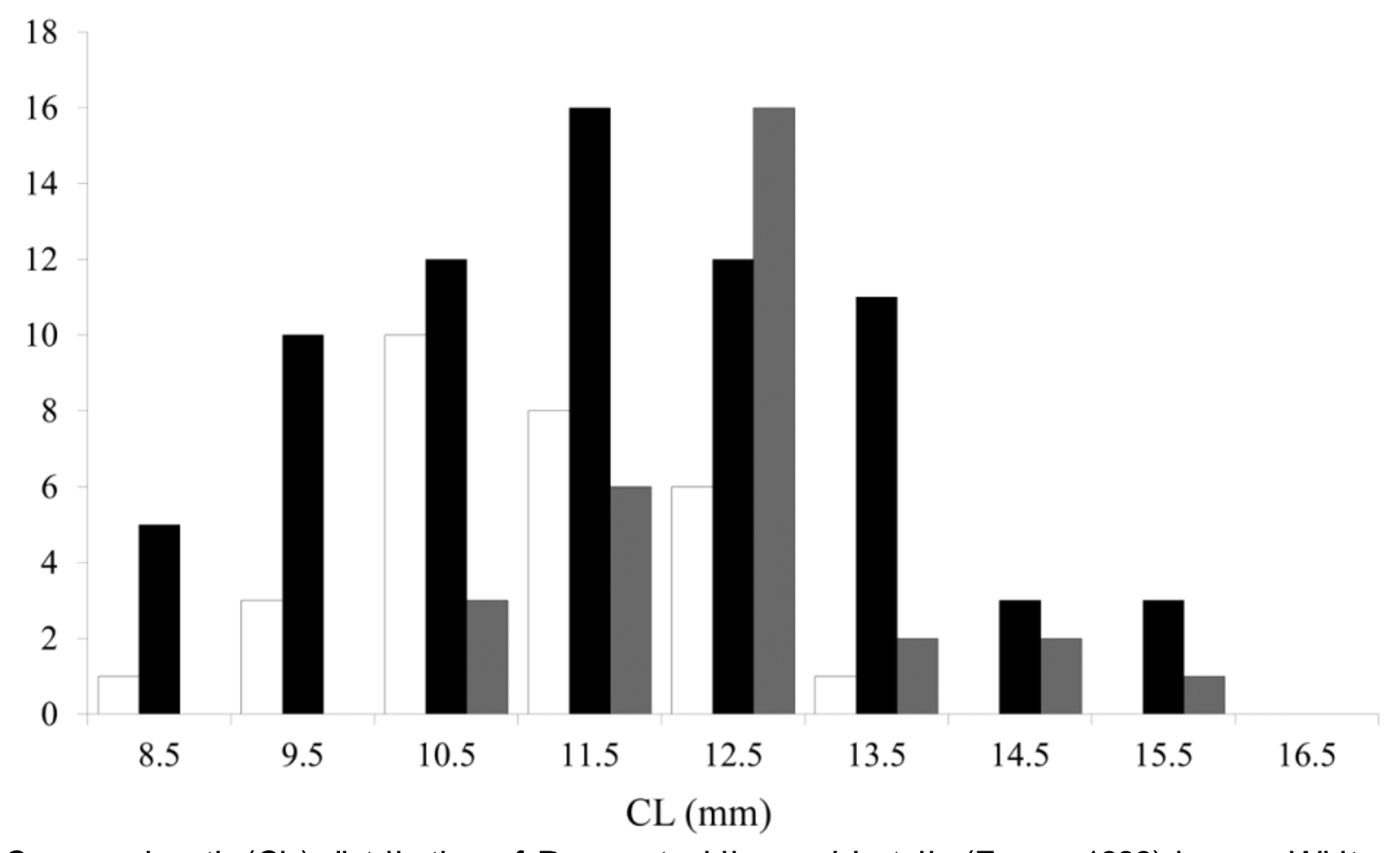

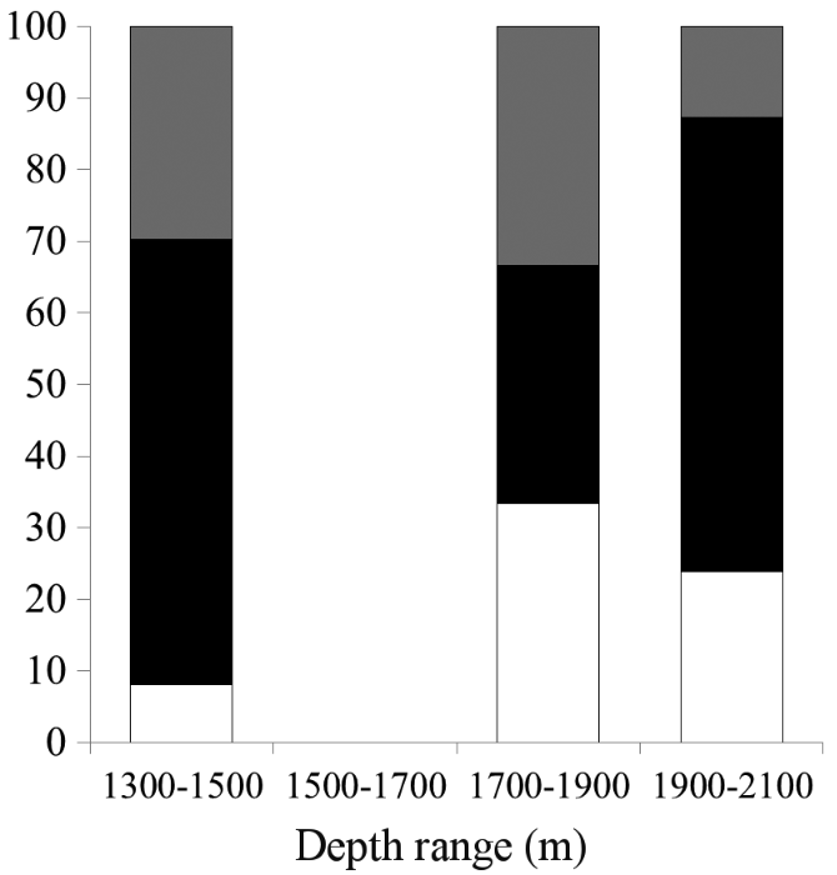

Considering the material collected off the northern BCP during this study, 28 males, 76 females and 32 ovigerous females (30% of all females) (M:F = 1:3.6) were available. Size varied from 8.8 to 13.2 mm CL in males, from 8.4 to 16.1 mm CL in females, and from 10.2 to 15.6 mm CL in ovigerous females. Statistical comparisons of size distributions across depth strata revealed almost significant differences (K-W test H2,133=5.79, p =0.05). A pattern of larger organisms found at greater depths (1701–2100m) was detected ( Figure 6 View FIGURE 6 ) and differences were almost significant between 1301–1500 and 1701–1900 m (K-W test, n 1301-1500 =37, n 1701-1900 =33, p =0.08). Overall, females were significantly larger than males (Mann-Whintey U test, U =1066.0, p <0.05) ( Figure 7 View FIGURE 7 ) and ovigerous females were larger than non-ovigerous females (Mann-Whintey U test, U =742.5, p <0.01). Sex proportions differed across all depth strata (χ2 test all p <0.05). Males were essentially present from 1701 to 2100 m and absent at shallower depths. Instead, greater proportions of ovigerous females were observed at 1301–1500 m and 1701–1900 m ( Figure 8 View FIGURE 8 ).

Depth range (m) TALUD XVI and XVIB TALUD XV FIGURE 5. Standardized mean (a) density (numbers of individuals ha -1) and (b) biomass (in wet weight, g ha -1) of Parapontophilus occidentalis ( Faxon, 1893) in the northern Baja California by depth range.

Within the Gulf of California (see Table 1), M:F ratio was 1:7, much more in favour of females than in the case of the Baja California material. Percentage of ovigerous females (21%), however, was similar.

Fecundity. Due to the fact that collected ovigerous females presented a very narrow size range, no attempt was made to fit a logistic function between CL and maturity. Number of eggs carried by ovigerous females was extremely variable (7 to 998; mean=282; SD=277) and there was no clear relationship between female size and number of eggs (y = -13.649x + 450.28; R2 =0.0025). Eggs of females carrying very few eggs (<100) were examined carefully in order to detect the possibility that embryos had reached hatching size, thus explaining the reduced number of eggs remaining attached to the females. However, in all females with less than 100 eggs the development of embryos was in its early (no sign of structure) or intermediate (embryos with appendage buds, no eye pigments, large amount of remaining vitellus) phase. Using only data of females carrying at least 100 eggs (i.e., 124 to 998), egg mass weight varied from 0.036 to 0.181 g (egg/body ratio, 4 to 13%). Size of oval-shaped eggs also varied considerably, from a minimum of 0.515 mm to a maximum of 0.922 mm. Average lengths of eggs within a specimen varied from 0.653 (SD= 0.032 mm) to 0.827 mm (SD= 0.039 mm). There was no clear correlation between size of ovigerous females and size of eggs (y=-0.0109x + 0.8555; R2 =0.0724). The larger ovigerous females with more than 100 eggs (i.e., 13.7 to 14.9 mm CL) carried eggs with an average size comprised between 0.694 and 0.716 mm, while the smallest ovigerous females (i.e., 10.7 to 11.1 mm CL) carried eggs of 0.687 to 0.827 mm (average sizes).

Only four ovigerous females were collected within the Gulf of California ( Hendrickx 2012b), and a similar variation was observed regarding number of eggs carried by females of 11.3 to 14.6 mm CL: from a low 3 to 450 eggs.

There are no data available on the reproduction seasonality or frequency of P. occidentalis . Considering samples collected off Baja California and the material reported previously ( Hendrickx 2012b), ovigerous females were found in one sample in April 2005, in February 2007 ( Table 1), and in July 2012, and in six samples in May 2014.

Relationship with environmental variables. Minimum and maximum values measured for the different environmental variables in the northern BCP are shown in Figure 9 View FIGURE 9 together with minimum and maximum thresholds for P. occidentalis . At the northern BCP, P. occidentalis was collected at dissolved oxygen concentrations (DO20mab) ranging from 0.76 to 1.83 ml l -1, at temperature (T20mab) from 2.1 to 3.4 °C, and salinity (S20mab) from 34.54 and 34.63 kg g -1. It is important to note that maximum thresholds observed for DO20mab and S20mab and the minimum for T20mab coincide with those that were sampled, as they correspond to the deeper stations carried out. Considering that P. occidentalis has been reported to depths of ca. 4000 m ( Faxon, 1893, 1895; Komai, 2008; Wicksten, 2012), it is likely that the species is distributed deeper and can tolerate larger ranges of these variables. Parapontophilus occidentalis was collected in sediments containing between 1.82 % and 5.38 % of OC sed, 0 % and 37.38 % of sand, 2.59 % and 15.5 % of clay and 52.11 % and 86.98 % of silt. The values of the environmental variables measured in the station of the southern BCP where three specimens of P. occidentalis were all within the same range of values.

Draftsman plot revealed that T20mab was negatively correlated with DO20mab and positively with S20mab. Both O 20mab and S20mab were positively correlated with depth and T 20mab showed a negative correlation. Silt content of sediments was positively correlated with OC sed and negatively correlated with sand content of sediments. Positive correlations were also observed between PPC-3 and PPC-2 and PPC-4. Therefore, variables retained for GLMs were T20mab, silt and clay content in sediments, PPC-1, PPC-3, PPC-5 and PPC-6.

Non-parametric Spearman rank correlation between density of P. occidentalis and environmental variables considering the entire depth range sampled in the northern BCP revealed significant positive correlations with DO20mab and S20mab, and negative correlations with T20mab and PPC-1 ( Table 3 View TABLE 3 ). Besides, almost significant correlations were observed with clay % in sediments (positive correlation) and with sand % in sediments and PPC- 5 (negative correlations).

Generalised Linear Models performed on biomass data within the depth distribution of the species in the northern BCP (i.e., 1296–2093 m) explained 66% of the total deviance, including T20mab, PPC-5 and silt % in sediments as explanatory variables ( Table 4 View TABLE 4 ).

TABLE 2. Number of hauls performed off the west coast of the northern (TALUD XVI and XVI-B) and southern (TALUD XV) Baja California Peninsula, number of individuals captured (# ind.) and frequency of occurrence (% F) of Parapontophilus occidentalis (Faxon, 1893) in hauls by depth range.

| # of hauls | # ind. | %F | # of hauls | # ind. | %F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 701–900 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 901–1100 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| 1101–1300 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| 1301–1500 | 8 | 37 | 63 | 3 | 3 | 33 |

| 1501–1700 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| 1701–1900 | 1 | 33 | 100 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1901–2100 | 4 | 63 | 100 | 0 | ||

| 2101–2300 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Parapontophilus occidentalis ( Faxon, 1893 )

| Hendrickx, Michel E. & Papiol, Vanesa 2015 |

Parapontophilus occidentalis

| Hendrickx 2012: 293 |

| Moscoso 2012: 60 |

| De 2011: 461 |

| Komai 2008: 287 |

| Guzman 2005: 288 |

| Retamal 2002: 204 |

Pontophilus occidentalis

| Wicksten 2003: 69 |

| Kameya 1997: 92 |

| Hendrickx 1993: 306 |

| Faxon 1893: 200 |