Tragulus javanicus

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2004.00091.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B54917-FFF9-9C4C-FEC6-FF72FEBDBA45 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Tragulus javanicus |

| status |

|

T. JAVANICUS View in CoL / KANCHIL GROUP

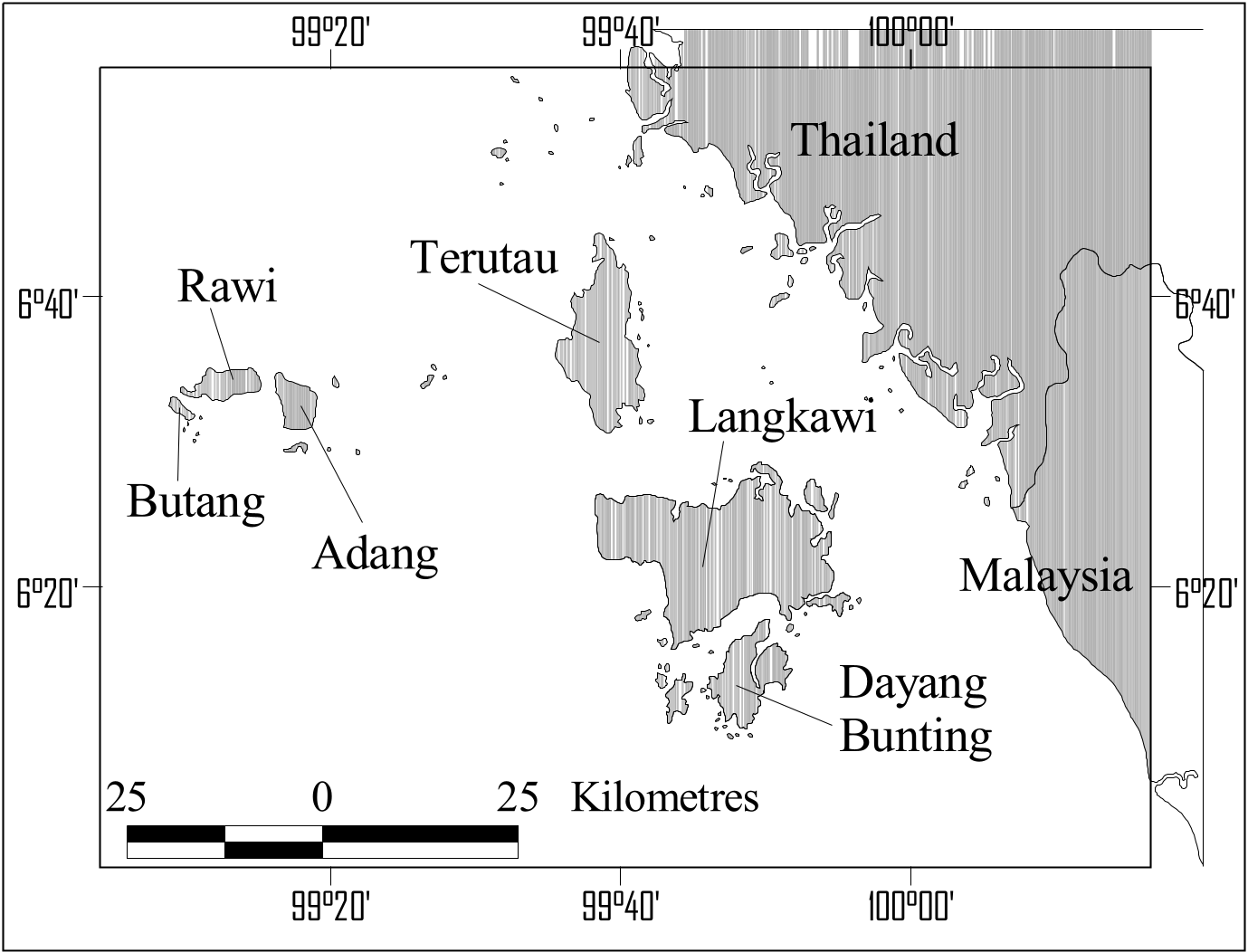

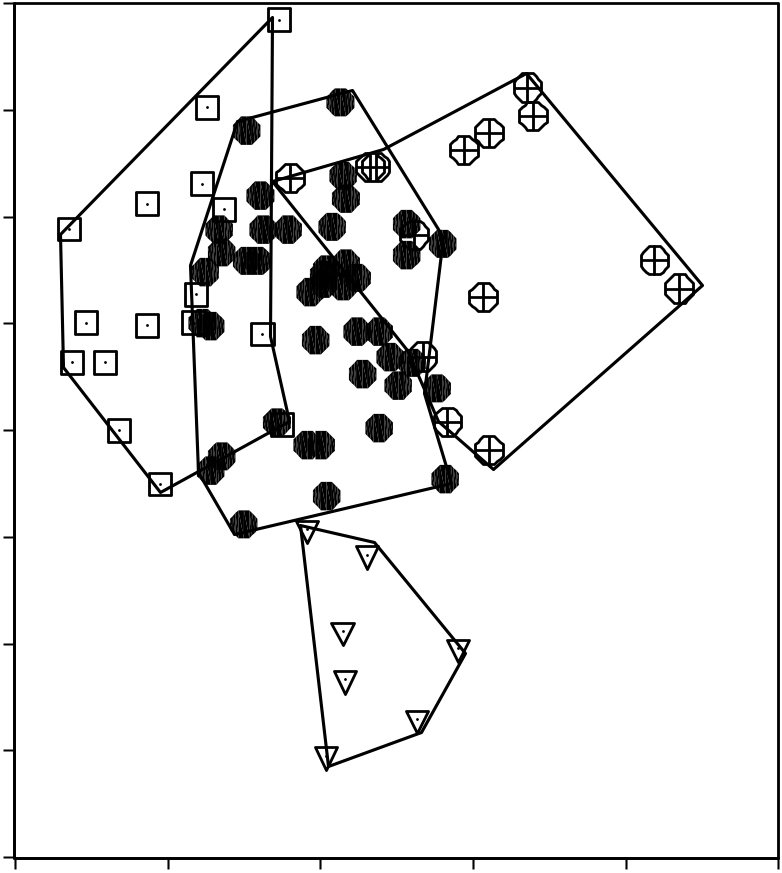

Experimentation with different geographical samples of the T. javanicus / kanchil group in a discriminant analysis revealed that there were considerable differences between skulls of adult specimens from Borneo, Java, the islands west of the Malay Peninsula (Langkawi, Butang, Rawi, and Pipidon, see Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ), and a combined group of specimens from Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, mainland Asia, and all islands on the Sunda Shelf ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). In particular, the west Malay islands specimens were well separated from the others. They were primarily distinguished from the other skulls by their narrow auditory bullae, and narrow, short skulls (low value for ZW, CW, and BPL in function 2, see correlation matrix and Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). The Javan skulls were also distinguished by their narrow auditory bullae and narrow braincase, and they also have longer and higher mandibles, a character they shared to some extent with the Langkawi, Rawi, and Adang skulls. Bornean skulls had wider auditory bullae, a wider braincase and smaller mandibles, especially those from Sabah. The specimens from Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, mainland Asia, and the small Sundaland islands were intermediate in these characters (see Table 7 for an overview of the mean values).

Interestingly, when we added the measurements for OHO to the analysis, and treated the Sabah specimens as a distinct group, the separation between the remaining groups increased significantly to a 94% accurate classification ( N = 50), and in particular the group of specimens from Java stood out for their lack of overlap with other groups ( Fig. 11). This character was only available for one of the Terutau/Langkawi specimens, and therefore it could not be used to investigate the relation of T. javanicus / kanchil from these islands to others. Regardless, OHO and to a lesser extent OHB were important characters that differentiated between Bornean and Javan T. javanicus / kanchil ( Fig. 11, and corresponding correlation matrix). In Figure 11, we also show that three specimens (RML 3774, 4600, 4601) from Padang, Sumatra, consistently grouped with the Sabah specimens. When all young adult and young adult–adult specimens were added to this analysis, the three groups were still separated with an accuracy of 87.7% ( N = 73).

The full implications of these results will be addressed in more detail in the Discussion section, but it is appropriate to note at this point that it would be difficult to continue to associate the Java and Sumatra /Borneo/Malay peninsula smaller mouse-deer in a single species. For the latter group, the name T. kanchil has priority.

Variation within Java

Dobroruka (1967) reported the existence of two distinct subspecies of mouse-deer on Java, which he called T. j. pelandoc (from the north coast of West Java Province) and T. j. focalinus (from the western part of Java and to the southern coast). A principal component analysis of the Javan skulls revealed some grouping of specimens from the two same geographical areas, especially those from central West Java and to a lesser extent those from the south coast ( Fig. 12). The three specimens from the north coast, including the type locality of T. j. pelandoc as fixed by Dobroruka (1967), appeared to group with Table 7. Means and standard deviations (SD) for skull measurements on adult T. javanicus and T. kanchil specimens (mm)

those from the south coast, where T. j. focalinus should occur. Because we had only photographed three of the 26 corresponding skins it was impossible to determine whether these two groups coincided with the subspecific characteristics of the taxa described by Dobruruka.

Variation within the Borneo, Sumatra, Malaya, Asian mainland and small Sundaland islands group

Borneo and adjacent islands. There were clear size differences between skulls of T. kanchil from different regions of Borneo, with larger specimens occurring in

2

1

0

2

Function -1

-2 West Malay islands

-3 Sumatra, Malaya,

Asia, Sunda islands

Sabah and smaller specimens in West Kalimantan and Sarawak ( Table 8). In particular, the relatively wide skulls and large bullae of the Sabah specimens differentiated them from Sarawak and West Kalimantan specimens.

In a principal component analysis, these Sabah and Sarawak / West Kalimantan groups completely separated ( Fig. 13). We used this analysis to allocate three specimens from East Kalimantan to the two different groups: one specimen ( ZMA 22.824 View Materials ) from the area between the Sebuku and Sembakung Rivers, just south of the Sabah – East Kalimantan border, clearly grouped with the Sabah specimens, whereas two specimens ( ZMC 08198; 08200) from the Bengen River in central East Kalimantan ( 0°31N, 115°53′E) grouped with the Sarawak / West Kalimantan group. In the earlier mentioned discriminant analysis of all Javan T. javanicus specimens, T. kanchil from Sabah, and all other T. kanchil specimens, the Sabah group almost completely separated from a group combining all other T. kanchil specimens, except for three specimens from Padang, West Sumatra ( RML 3774 , 4600 , 4601 ), that consistently grouped with the Sabah specimens GoogleMaps .

One specimen (FMNH 85912) was omitted from the analysis because it was very unusual. This specimen from Kalabakan, Tawau, Sabah, was labelled as a male, and its age determined as young adult; but it had very small ( 2–3 mm) canines that looked more robust than normal female canines, and its body weight was only 1500 g, as indicated on the label. Possibly this was a sick animal. We were unable to study the skin and it is unclear whether this is an aberrant specimen or something taxonomically different from the normal Sabah form.

Sumatra, Asian mainland and the Malay/Thai peninsula. Above we have shown that T. versicolor is distinct from all T. napu taxa. When we compared all T. kanchil subspecies of Indochina and the Malay Peninsula with T. versicolor , it became clear that T. versicolor was also distinct from them ( Fig. 14). T. versicolor was primarily distinguished from the others by the high value for BPL and ZW (see correlation matrix in Fig. 14).

Within T. javanicus of the Malay Peninsula and Asian mainland there was little variation in skull dimensions ( Table 9). Only the type specimen of T. k. williamsoni , from northern Thailand, stood out by its large size. This specimen was larger than the means of all other mouse-deer from the Asian mainland and Malaya (except T. napu ), whereas for most of the individual measurements it was also larger than the maximum values for the Malayan and mainland Asia T. kanchil subspecies. Neither a principal component analysis nor a discriminant analysis could meaningfully separate the other specimens from mainland Asia and the Malay/Thai peninsula into geographical groups. There was some differentiation between skulls assigned to T. k. fulviventer and T. k. ravus , from the south and centre of the Malay peninsula, respectively, but the two groups did not separate well in a principal component analysis. In a discriminant analysis that included specimens of T. k. fulviventer , T. k. ravus / T. k. angustiae (grouped together because of geographical proximity and low number of specimens for more northerly T. k. angustiae), T. k. affinis from Indochina, and specimens from the west Malay islands (Langkawi and Rawi), the T. k. ravus specimens grouped closely with those from the west Malay islands ( Fig. 15). Also, the T. k. fulviventer and T. k. affinis specimens grouped closely together. Classification accuracy was 79%. When we added the Sumatra specimens to this analysis they largely overlapped with T. k. fulviventer and T. k. ravus / T. k. angustiae.

The skins of the Malayan and mainland Asian subspecies differed to some extent. In the northern Malay / Thai peninsula and on the Asian mainland, the upper parts were generally duller (less reddish) and less suffused with black than those from the southern Malay Peninsula, which tended to be more reddish brown. Most mainland Asia specimens had vague nape streaks (or lacked them completely as in the T. k. williamsoni specimen), whereas they were clear in most specimens from the Malay Peninsula. The most northern specimens of the darker form originated from Bang Nora , Siam ( ZRC 4.4850 View Materials and 4.4851) at 6°25′60″N, but we could not identify the locality of a dark specimen from Lam Ra Trang, northern Malay peninsula ( ZRC 4.4881 View Materials ). The most southern specimen of the lighter form probably originated from the Krabi area, assuming that this is what the label localities ‘Grahi’ and ‘Grabi’ refer to. None of the means of all measurements of the northern and southern form are significantly different .

First component

A principal component analysis of the Sumatran specimens did not reveal much geographical structure in the data, but this may have been because there was only one specimen from South Sumatra in the analysis, whereas the majority were from north Sumatra, and three specimens from west Sumatra. The one south Sumatran specimen stood out because of its wide auditory bullae and related small interbullae distance, but it is unclear whether this result is of any significance .

| ZMC |

Deptment of Biology, Zunyi Medical College |

| T |

Tavera, Department of Geology and Geophysics |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |