Pseudalopex griseus (Gray, 1837)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6331155 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6585161 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03ACCF40-BF24-FFDD-7ED2-F43CFADFD812 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Pseudalopex griseus |

| status |

|

16. View On

South American Gray Fox

Pseudalopex griseus View in CoL

French: Renard d’Argentine / German: Argentinischer Kampfuchs / Spanish: Zorro de Magallanes

Other common names: Chilla, Small Gray Fox

Taxonomy. Vulpes griseus Gray, 1837 , Chile.

Formerly believed to include an island form, which since has been recognized as Darwin’s Fox. The Pampas Fox has recently been suggested to be conspecific with P. griseus on the basis of a craniometric and pelage-characters analysis, leading to the conclusion that P. gymnocercus and P. griseus are clinal variations of one single species, namely Lycalopex gymmnocercus . Four subspecies are recognized.

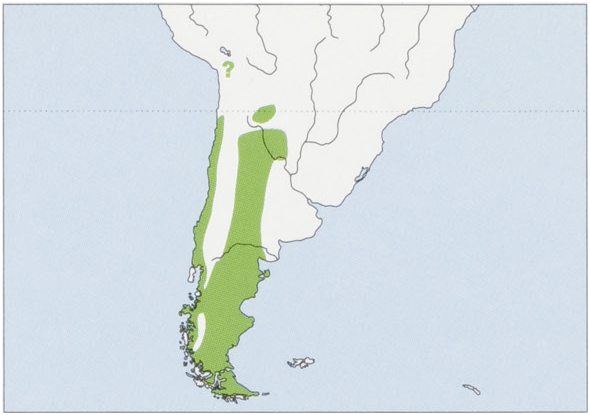

Subspecies and Distribution.

P. g. griseus Gray, 1837 — Argentine and Chilean Patagonia.

P. g. domeykoanus Philippi, 1901 — N & C Chile, possibly S Peru.

P. g. gracilis Burmeister, 1861 — W Argentina (Monte Desert).

P. g. maullinicus Philippi, 1903 — S Argentine and Chilean temperate forests.

Introduced ( griseus ) in Tierra del Fuego. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 50- 1-66 cm, tail 11-5-34- 7 cm; weight 2-5- 5 kg. A small fox with large ears and a rufescent head flecked with white. Well-marked black spot on chin. Coat brindled gray, made up of agouti guard hairs with pale underfur. Black patch across thighs. Legs and feet pale tawny. Underparts pale gray. Tail long and bushy, with dorsal line and tip black and a mixed pale tawny and black pattern on the underside. The cranium is small, lacking an interparietal crest. Teeth widely separated. The dental formulaisI13/3,C1/1,PM 4/4, M 2/3 = 42.

Habitat. Steppes, grasslands and scrublands. South American Gray Foxes generally inhabit plains and low mountains, but they have been reported to occur as high as 3500-4000 m. Although they occur in a variety of habitats, they prefer shrubby open areas. In Chile, they hunt more commonly in flat open patches of low scrub. In Chilean Patagonia, their typical habitat consists of shrubby steppe composed of coiron (Festuca spp., Stipa spp.) and nires (Nothofagus antarctica). Burning and destruction of forests for sheep farming seems to have been advantageous for these foxes. In Torres del Paine National Park, 58% of twelve individuals monitored showed preferential use of matorral shrubland or Nothofagus thicket habitat within their home ranges. In the Mendoza desert, Argentina, they prefer the lower levels of shrubby sand dunes rather than higher sections. They tolerate a variety of climates, including hot and dry areas such as the Atacama coastal desert in northern Chile (less than 2 mm average annual rainfall, 22°C mean annual temperature), the humid, temperate Valdivian forest (2000 mm average annual rainfall, 12°C mean annual temperature), and the cold environment of Tierra del Fuego (c. 400 mm average annual rainfall, 7°C mean annual temperature).

Food and Feeding. South American Gray Foxes are omnivorous generalists, feeding on a variety of foods, including mammals, arthropods, birds, reptiles, fruit, and carrion. Fruits ingested include berries of Cryptocarya alba and Lithraea caustica in Chile, pods of Prosopis spp., and the berry-like fruits of Prosopanche americana and of several Cactaceae in Argentina. A tendency to carnivory is apparent, however, since vertebrates, especially rodents, are reported to be the most important prey in most studies. Small mammals were the most frequently occurring vertebrate prey in most sites in the Chilean matorral and in the temperate rainforests of southern Chile. In Torres del Paine National Park, the European Hare was the most represented vertebrate prey, followed by carrion and akodontine rodents. In the Argentine Patagonian steppe, carrion was the most important food item in 42 stomachs collected in winter (representing 62% of biomass ingested), followed by hares and cricetine rodents. In Argentina’s southern Patagonia, diet also consisted primarily of carrion, followed by birds, rodents, and fruit. Diet included invertebrates, carrion, birds, and rodents in Tierra del Fuego. In the harshest habitats ofits range, the foxes’ diets include increasingly higher proportions of non-mammal food as small mammal availability decreases. Lizards were the most consumed vertebrate prey in winter, the season of lowest small mammal availability in coastal northern Chile. Small-mammal consumption decreased from autumn to summer, and fruit consumption increased. In central Chile, berries appeared in 52% of the droppings (n = 127) collected in autumn, while in spring, when small mammal availability is highest, berries were present in only 18% of the feces (n = 62). In Mendoza (Monte desert), fruit was represented in 35% of feces (n = 116), followed by small mammals (19% frequency of occurrence). Foraging occurs mostly in open areas. Although hunting groups of up to 4-5 individuals have been reported, South American Gray Foxes mostly hunt solitarily, except perhaps at the end of the breeding season, when juveniles may join the parents in search of food. In Torres del Paine National Park, the most common foraging behavior consisted of slow walking, with abrupt, irregular turns through low vegetation. The same report noted that prey appear to be located by sound, sight, and smell. Mice are captured with a sudden leap or by rapidly digging holes. Scavenging is common, as well as defecation on and around Guanaco (Lama guanicoe) and domestic goat carcasses. Caching behavior has also been reported.

Activity patterns. Direct observations and prey activity patterns suggest that South American Gray Foxes are crepuscular, although they are commonly seen during the day. Radio-tracking showed that they were primarily nocturnal in Torres del Paine National Park, whereas they were active during both day and night in Reserva Nacional Las Chinchillas.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The basic component of social organization in Torres del Paine National Park is the breeding monogamous pair, accompanied by occasional female helpers. Male dispersal and occasional polygyny is also reported. Solitary individuals were seen from March to July, while pairs comprised 42% of sightings during August. The male and female of an observed pair maintained an exclusive home range year-round, which did not overlap with home ranges of neighboring pairs. Intraspecific interactions were few and usually aggressive. Individual home range sizes (n = 23) averaged 2-0 km”.

Breeding. Mating occurs in August and September, the gestation period is 53-58 days and 4-6 pups are born in October. Dens are located in a variety of natural and manmade places such as a hole at the base of a shrub or in culverts under a dirt road The pups may be moved to a new location during the nursing period. During the first few days the mother rarely leaves the den and the male provisions her with food. Pups are cared for by both parents on an approximately equal time basis. Young foxes start to emerge from the den when they are about one month old, and start to disperse (8-65 km) at 6-7 months of age. Two interesting phenomena concerning breeding behavior may occur: litters of two females combine (associated with polygyny) and the presence of female helpers. Both seem to be related to food availability and litter size. Female helpers contribute by bringing provisioning food to the den and increasing anti-predator vigilance.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. Considered “locally common” in Argentina and stable in the southern half of the country where habitat is more favorable. Reported to have expanded their range in Tierra del Fuego since being introduced there: in 1996 their density was estimated at 1 per km®. Hunting them and fur trading are legal in Argentine Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. All Chilean populations are currently protected by law, except for those from Tierra del Fuego. The main threat to South American Gray Fox populations in the past was commercial hunting for fur. Hunting intensity has apparently declined in recentyears. Illegal killing still occurs in some regions,as the foxes are perceived to be voracious predators of small livestock, poultry and game. The usual means of hunting are by shooting, dogs, poison, snares, and foothold traps. Around 45% of the mortality documented in Torres del Paine National Park resulted from either poaching or dog attacks. Road kills are frequently observed in Argentina, especially in summer.

Bibliography. Cabrera (1958), Campos & Ojeda (1997), Duran et al. (1985), Gonzalez del Solar & Rau (2004), Gonzalez del Solar et al. (1997), Jaksic, Jiménez et al. (1990), Jaksic, Schlatter & Yanez (1980), Jaksic, Yanez & Rau (1983), Jayat et al. (1999), Jiménez (1993), Jiménez, Yanez, Tabilo & Jaksic (1996), Johnson & Franklin (1994a, 1994b, 1994c), Mares et al. (1996), Marquet et al. (1993), Martinez et al. (1993), Medel & Jaksic (1988), Novaro, Funes & Walker (2000), Rau et al. (1995), Simonetti et al. (1984), Yanez & Jaksic (1978), Zunino et al. (1995).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Caniformia |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pseudalopex griseus

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2009 |

Lycalopex gymmnocercus

| Burmeister 1854 |

Vulpes griseus

| Gray 1837 |

P. griseus

| Gray 1837 |

P. griseus

| Gray 1837 |