Xiphinema, COBB, 1913

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12316 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03A06734-FFF4-FFD4-562B-FB63FB0FFDFC |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Xiphinema |

| status |

|

THE XIPHINEMA AMERICANUM- GROUP

Sequences of nuclear rDNA and mtDNA genes, particularly D2-D3, ITS1, and partial coxI, have proven to be a powerful tool for providing accurate and molecular species identification in Longidoridae ( Chen et al., 2005; He et al., 2005; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez et al., 2012, 2013; Zasada et al., 2014). Our results confirm the usefulness of these markers in the X. americanum - group, as nucleotide differences amongst species ranged from 26 to 126 nucleotides for D2-D3, from eight to 270 nucleotides for ITS1, and from seven to 108 nucleotides for partial coxI within related sequences. The phylogenetic relationships inferred in this study based on the D2-D3 and ITS1 sequences mostly agree with the lineages obtained by Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez et al. (2010, 2012) and Zasada et al. (2014) for the phylogeny of the X. americanum- group.

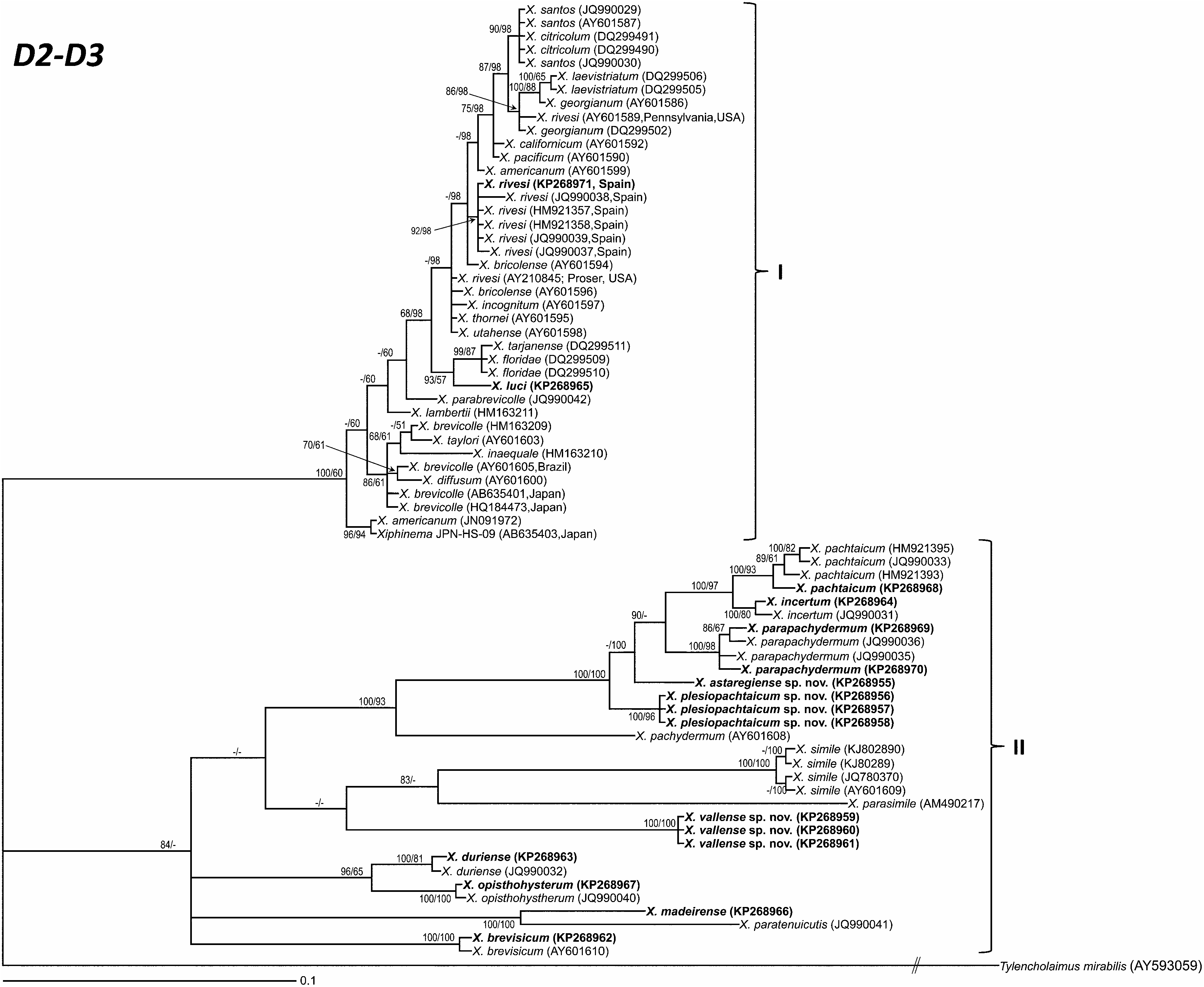

In order to understand the evolution of the X. americanum -group, it is important to confirm a correlation between the results obtained by conventional morphological approaches and new molecular methods. Two clearly separated major subgroups (clade I and II) were shown using both nuclear rDNA molecular markers (D2-D3 and ITS1). One subgroup was formed by X. americanum ‘ sensu stricto’ (clade I), whereas the other group was formed by other species (clade II; Figs 9 View Figure 9 , 10 View Figure 10 ). Species from clade II are more variable morphologically and morphometrically than the subgroup X. americanum ‘ sensu stricto’, as showed the long branch in the phylogenetic tree. The phylogeny separation for clade I was observed in coxI; however, it was not supported, probably because of its high mutation rate and the smaller fragment used in this study. However, coxI is a good marker for molecular identification in X. americanum -group as bar-coding. The three new species ( X. astaregiense sp. nov., X. plesiopachtaicum sp. nov., and X. vallense sp. nov.) were studied phylogenetically here and we have provided new sequences for X. madeirense and X. luci that may help with their identification (D2-D3 and ITS1, and coxI for the latter). The new sequence of X. rivesi provided in this research nested within the clade containing all previously sequenced Spanish populations. These sequences were different to other X. rivesi sequences deposited in GenBank, indicating the possibility of cryptic speciation as suggested by Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez et al. (2012). While for X. luci we provide two molecular markers and its phylogenetic position is defined in the genus. This species is closely related phylogenetically to X. floridae and X. tarjanense using D2-D3, but differs from X. floridae by a smaller c′ and a pointed tail tip. It differs from X. tarjanense by a smaller odontostyle, higher c′, smaller c, smaller body length, lip region set off from body profile, tail tip with pointed terminus, and longer tail length. Xiphinema astaregiense sp. nov. and X. plesiopachtaicum sp. nov. were clustered together using D2-D3 and ITS1 markers, whereas the phylogenetic relationship of X. vallense sp. nov. with these species was weak. The X. pachtaicum subgroup (clade II) is not well supported in major clades, and some small clades ( viz. X. duriense - X. opisthohysterum , X. madeirense – X. paratenuicutis ) and species ( X. brevisicum ) formed polytomies in this subgroup with the D2-D3 marker. Xiphinema madeirense and X. astaregiense sp. nov. did not show a position agreement with their morphological grouping using the ITS1 marker. Clades I and II showed different evolution rates based on their branch lengths and this could be a major point in resolving some clades. Another possibility is the polyphyletic origin of X. americanumgroup species and the loss of some species in the clades or the incomplete sampling of this group within the genus Xiphinema . The partial coxI phylogeny did not show a clear relationship within the species in the X. americanum -group; however, this marker could be used as a good barcoding region in order to identify species.

Mapping morphological character evolution on the tree showed some putative evolution patterns for vulva position, a ratio, and total stylet length. Vulva position seems to have evolved from an anterior position to a more posterior position in clade II. The X. pachtaicum -subgroup (clade II) is characterized by a higher V value in the species groups analysed. This shift in the position is difficult to explain because of the lesser range in vulval position for the X. americanum -group (clade I) and the short and undifferentiated reproductive system in comparison to the X. non- americanum -group species. A more anterior vulva position seems to be more related to the functional regression of the anterior branch ( Coomans et al., 2001). However, X. americanum- group species have both branches functional and equally developed. Ratio a is related to nematode size and maximum body width; SIMMAP and MESQUITE analyses showed that in their ancestral stages nematodes of the X. americanum - group species were longer with a similar maximum body width. This character is represented by the X. pachtaicum -subgroup (clade II). We can assume this because maximum body width could be a more restricted character in comparison to body length because may be closely related with the soil particles were nematode move. In the MESQUITE analysis, stylet length seems to have evolved in X. americanum -group from a shorter to a longer stylet. However, the ancestral stage for the majority of the species was not clear. Nevertheless, stylet length is an important taxonomic and biological character, which is closely related to the feeding apparatus ( Jairajpuri & Ahmad, 1992). The several reversal states in some species could be related to additional adaptation and selection of specimens with a longer stylet because of vegetation (host-plant) changes during their evolution. Nematodes with a long stylet or semiendoparasitic feeding behaviour can feed on higher quality tissues such as phloematic cells ( Wyss, 1981; Böckenhoff et al., 1996). Mapping characters in Nematoda could be difficult, mainly because fast evolution and the possible restriction of morphotypes for soil habitat. Additionally, the value of individual characters is particularly amplified in organisms with limited cell counts and structural complexity, such as small invertebrates, which comprise the majority of metazoan phyla ( Ragsdale & Baldwin, 2010). The limited size of nematodes makes complete, three-dimensional reconstruction of entire organ systems a feasible goal ( Ragsdale & Baldwin, 2010). Characters such as amphidial fovea, tails, and male and female reproductive systems in Xiphinema could be investigated using these techniques. In this case, the existence of two clades without any species linking them makes it very difficult to understand the species evolution and it will be necessary in the future to find species linking both clades in the X. americanum- group. Xiphinema americanum s.l. species are markedly similar morphologically and probably evolving very fast between them. Which factors contribute to this speciation is still a matter of debate and the occurrence of novel verrucomicrobial species, endosymbiotic and associated with parthenogenesis in Xiphinema americanum -group species could help to find an explanation ( Vandekerckhove et al., 2000). However, more studies are necessary in order to understand the ‘possibly’ complex relationships of these endosymbiotic bacteria with their hosts and how these shape the phylogeny of this species-group.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.