Conocephalini

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2023.2231579 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6302611C-B300-4965-AD6A-C99711048B69 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8273988 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039F87E5-FF80-FFAF-5A90-A6B9FDB36220 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Conocephalini |

| status |

|

Conocephalini View in CoL View at ENA gen. et. sp. unknown

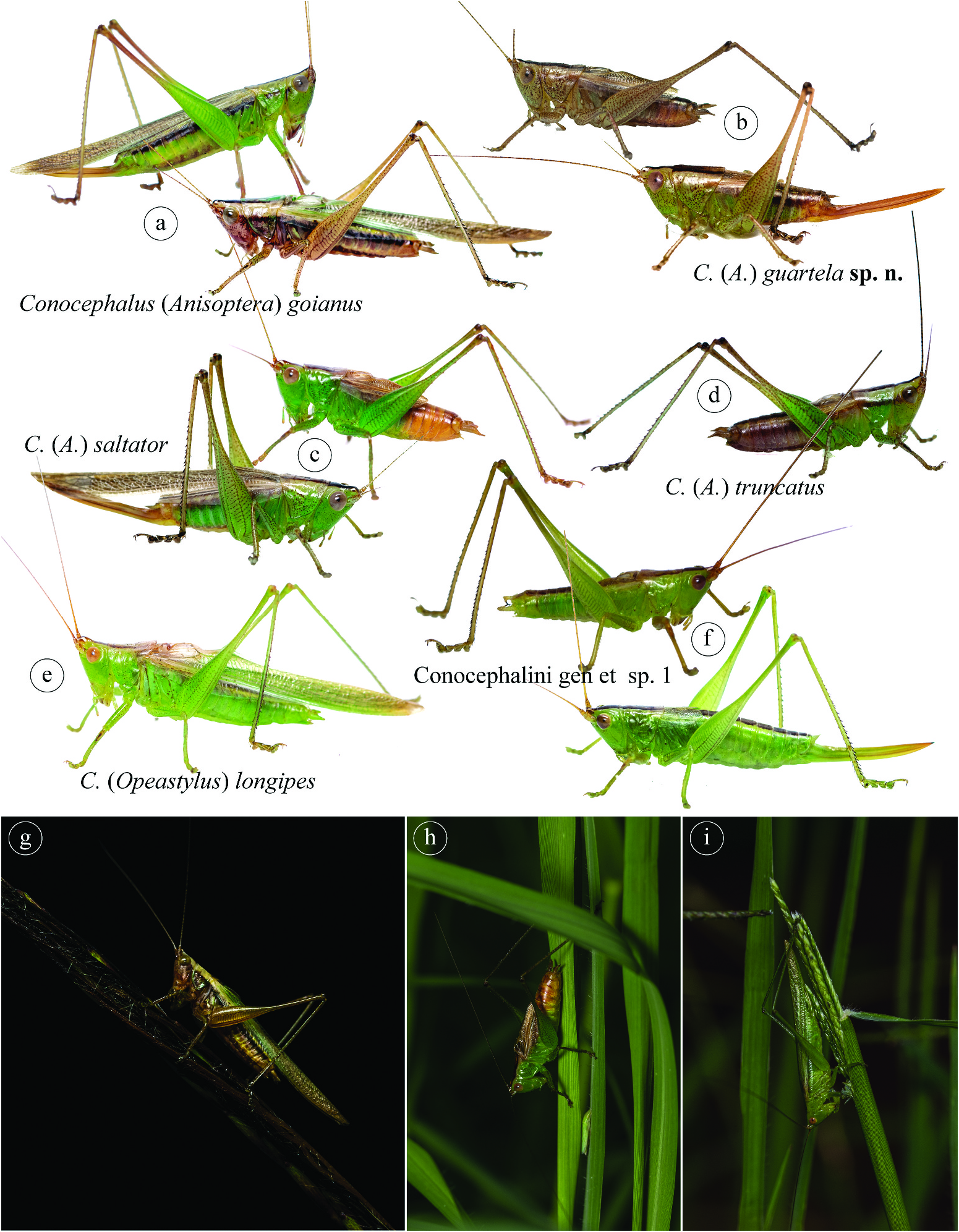

( Figure 5f View Figure 5 )

Comments

This species may belong to an undescribed genus, and is definitively a new species. The reasons for not describing this species or a new genus is due to the need for a phylogenetic approach in Conocephalini . A study of the systematics of the tribe is highly needed, and only this will bring the correct genus delimitation and relation, to truly understand whether this species belongs to a new genus, or to test the monophyly of the other genera of Conocephalini . The male cercus is falciform, with a long spine on its end, differing from most genera of the tribe that have a spine on the middle.

Examined material

Three males and two females, ′ Brasil, PR, Tibagi, Parque\Estadual do Guartelá [Guartelá State Park]\ 24.5660°S, 50.2561°W 10–13.ii.2021 Coleta ativa\noturna [nocturnal active collection] M. Fianco, D.N.\Barbosa & P.W. Engelking '; GoogleMaps one male and one female, same data, except ′ 09–12.xii.2020 ' and ′ M. Fianco & N.\Szinwelski '; GoogleMaps five females, same data, except ′ 08–11.iii.2021 ', ′Coleta ativa\diurna [diurnal active collection]' and ′ M. Fianco, D.N. \Barbosa & H. Preis '. GoogleMaps

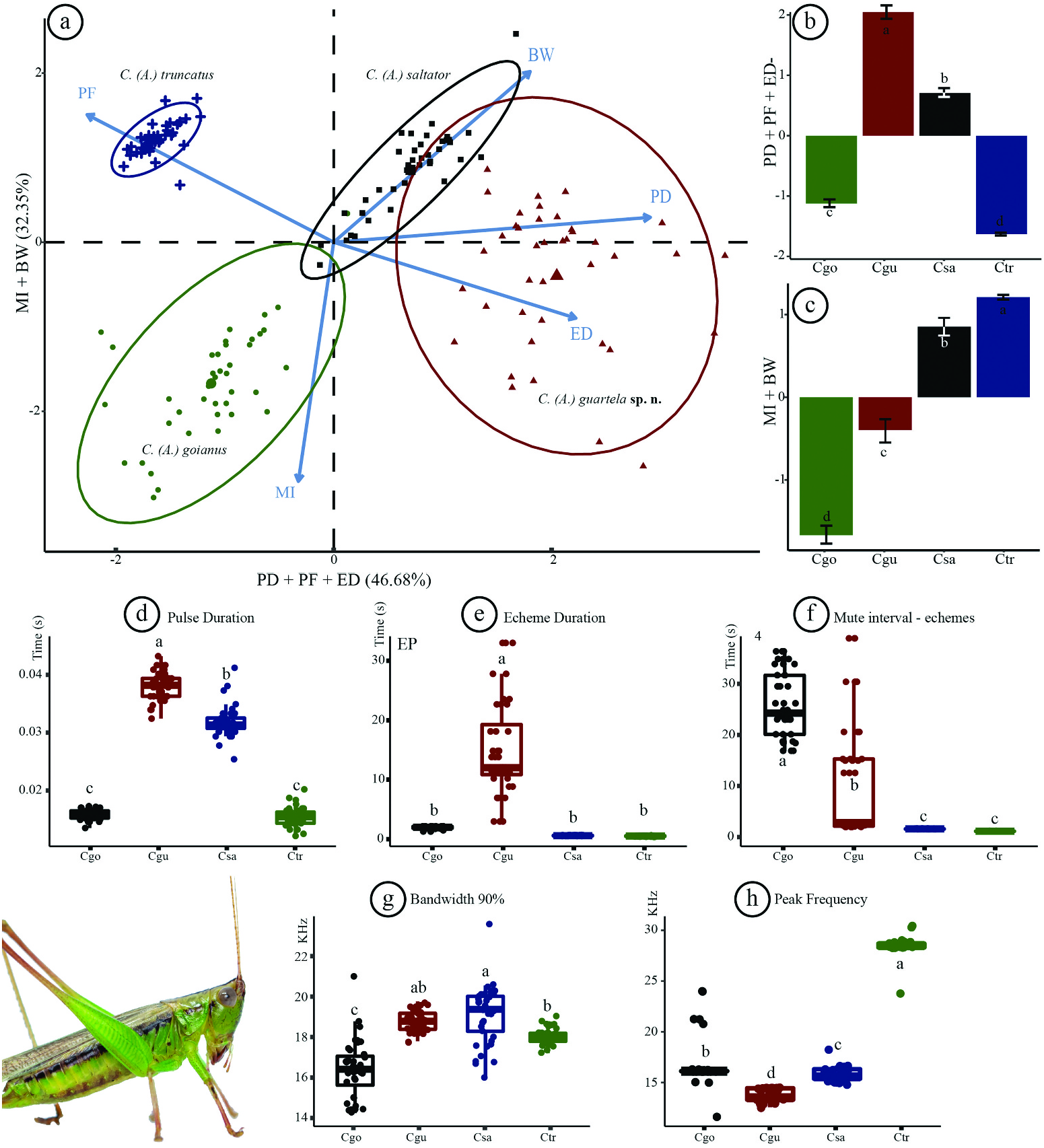

Statistical analysis of calling songs of Conocephalus (Anisoptera) ( Figure 7 View Figure 7 )

When the PCA was carried out, it was possible to observe that only two dimensions correspond to 79.21% of data exploration, so these two components were used to develop the analysis. The first dimension corresponds precisely to the main variables used in the katydid 's sound descriptions (the pulse duration, the echeme duration and the peak frequency), whereas the second dimension corresponds to the mute interval and the bandwidth ( Figure 7a View Figure 7 ).

According to the calling songs, Conocephalus ( A.) guartela sp. nov. can be easily distinguished from C. ( A.) truncatus by its echeme duration and peak frequency, both inversely proportional; additionally, in the analysis none of the sound variables of these two species were statistically equal, except bandwidth ( Figure 7a–h View Figure 7 ). The pulse duration is much higher in the new species, as is the mute interval and echeme duration, and the peak frequency is much higher in C. ( A.) truncatus . The pulse duration was statistically equal in C. ( A.) goianus and C. ( A.) truncatus , as well as the echeme duration ( Figure 7d–e View Figure 7 ) which can differentiate C. ( A.) guartela sp. nov. from all other species, as can the mute interval of echemes, and peak frequency ( Figure 7e–f, 7h View Figure 7 ). Peak frequency was the only variable that can distinguish all species of Conocephalus ( Anisoptera) subgenus from the GSP, although all other variables can, in some way, differentiate one or another species of the given subgenus ( Figure 7d–h View Figure 7 ).

Since acoustic behaviour can be understood as a trait of a given species, it influences the fitness of the individual that is singing, be it through sexual or natural selection. The sexual selection of sounds will affect only male–female interactions, with females perceiving the male 's fitness and choosing them as a sexual partner, whereas natural selection will affect the male–male and female– female intraspecific interactions, and male/female interspecific interactions, as is the case for acoustic oriented parasitoids to singing insects ( Drosopoulos and Claridge 2006). The calling songs may be affected by both sexual and natural selection, and as the peak frequency was the most important interspecific discriminant variable, we may infer the great importance of this sound property: katydids are a common prey for insectivorous bats, and bats have high hearing sensitivity peaks in their range of echolocation frequency ( Geipel et al. 2021), and are passive listeners, being attracted to the tettigoniid 's calling songs ( Falk et al. 2015); on the other hand, female katydids are predominantly attracted to the male peak frequency but use other sound variables for mate choice ( Bailey and Gwynne 1988; Tuckerman et al. 1993).

All Conocephalus ( Anisoptera) species are meadow katydids, and they are more exposed to bat predation since they are more often found and collected in open areas, and sing for long periods of time. On the contrary, forest katydids have calling songs with a narrow bandwidth and sing for short periods (see sound descriptions in Fianco et al. 2022 and field explorations done by Belwood and Morris 1987). It is interesting that the bandwidth of all Conocephalus ( Anisoptera) species was quite broad, ranging from 14 to more than 20 kHz, and bats have a preference for narrowband katydid calls. Could this broad band be an escape mechanism for bat predation moulded by natural selection?

Lehmann and Lehmann (2014) point out that the female choice for a determinate male seems to be severe and unidirectional since these characteristics are often the most fundamental and influence several biological aspects of the organisms, therefore reflecting greater physical aptitude. These findings strengthen the fact that insect sounds are subject to intense sexual selection. Thus, sound characteristics are fundamental in the biology of katydids, and their analysis is an important tool in taxonomy since they are useful to differentiate species, as proposed by Walker (1964). Often, katydids are not described or are wrongly synonymised due to the lack of a description of their calling songs, as highlighted by Walker (1964).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Conocephalinae |

|

Tribe |

Conocephalini |