Kobus vardonii ( Livingstone, 1857 )

Rduch, Vera, 2020, Kobus vardonii (Artiodactyla: Bovidae), Mammalian Species 52 (994), pp. 86-104 : 88-92

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1093/mspecies/seaa007 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4FAAFCF0-DFC6-476F-9890-93A7D63F5977 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/038FF23E-064D-2D38-DACB-FF32FE27F925 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Kobus vardonii ( Livingstone, 1857 ) |

| status |

|

Kobus vardonii ( Livingstone, 1857) View in CoL

Puku

Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857:256 , plate between pages 70–71. Type locality “Thirty or forty miles above Libonta ” later identified as “ Barotseland, Northern Rhodesia [today Zambia], at about 40°30’S, 23°15’E ” by Moreau et al. (1946:437).

Heleotragus vardonii: Kirk, 1864:657 . Name combination.

Cobus vardoni: Selous, 1881:759 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Eleotragus Vardoni : Huet, 1887:83. Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Adenota vardoni: Matschie, 1895:126 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Cobus senganus Sclater and Thomas, 1897:145 . Type locality “Senga, Upper Luangwa River, W. of the N. end of Lake Nyasa: altitude 2500 feet.” Moreau et al. (1946:437–438) proposed that a more accurate type locality would be upper Luangwa Valley rather than upper Luangwa River.

Cobus vardoni typicus: Selous, 1899:294 . No type locality specified, name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Cobus vardoni senganus: Bryden, 1899: 299 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Cobus [ Adenota ] vardoni: Lydekker and Burlace, 1914:209 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Kobus (Adenota) vardoni: Lydekker, 1914:268 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Kobus vardoni vardoni: Lydekker, 1914:269 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Kobus vardoni senganus: Lydekker, 1914:269 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Adenota vardonii vardonii: Allen, 1939:511 . Name combination.

Adenota vardonii senganus Allen, 1939:511 . Name combination.

Kobus vardonii: Best et al., 1962:83 View in CoL . First use of current name combination.

Kobus kob vardoni: Haltenorth, 1963:92 . Name combination, incorrect subsequent spelling of Antilope Vardonii Livingstone, 1857 .

Kobus kob senganus: Haltenorth, 1963:92 . Name combination.

Kobus senganus: Cotterill, 2000:168 . Name combination.

Kobus vardonii senganus: Grubb, 2005:721 View in CoL . Name combination.

Kobus vardonii vardonii: Grubb, 2005:721 View in CoL . Name combination.

CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Context as for genus. Currently, Kobus vardonii View in CoL is considered monotypic ( Grubb 2005; Groves and Grubb 2011; Huffmann 2011). However, Cotterill (2000, 2003), based on his species definition, considers K. vardonii View in CoL and K. senganus as evolutionary species (see “Nomenclatural Notes”).

NOMENCLATURAL NOTES. Livingstone (1857:256) was the first to mention this antelope in his journals of “ Missionary travels and researches in South Africa ” and named it in a short footnote: “I propose to name this new species Antilope Vardonii , after the African traveler, Major Vardon.” The specific epithet according to this first mentioning is vardonii . Attributing the antelope to another genus, Heleotragus, Kirk (1864:657) maintained the epithet and provided a short description. A slightly more detailed description is provided by Selous (1881:759). However, while presenting his new name combination, Cobus vardoni , and when he cited Kirk by writing Heleotragus vardoni , the specific epithet lost the second i. Only Allen (1939:511) again made use of the original specific epithet. Lydekker (1914:268) was the first to use Kobus vardoni and Best et al. (1962) were the first to use Kobus vardonii . Both spellings have been used alternately in the literature since then. The original spelling of Livingstone, vardonii , is considered correct because the Latinization of names (Vardonius) was common practice at his time. It has also been used, for example, by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2016), Skinner and Chimimba (2005), Grubb (2005), Jenkins (2013), and Castelló (2016). Kobus vardoni is thus an incorrect subsequent spelling, which is found in some reference works. Even Livingstone is not cited correctly by Groves and Grubb (2011) and Huffmann (2011).

The nomenclatural history of K. vardonii is associated with taxonomic issues concerning inter- and intraspecific relationships. The discussion whether Cobus senganus is a full species or a subspecies of K. vardonii had already started when C. senganus was described as a new species by Sclater and Thomas (1897:145). Considered as closely related, it was classified as the subspecies Cobus vardoni senganus by Bryden (1899:299). A similar question arose concerning K. vardonii and its relationship to Kobus kob . Matschie (1895:125) considered that both antelopes belonged to a separate genus, Adenota . Haltenorth (1963) considered K. kob vardoni and K. kob senganus as separate subspecies of K. kob . Ansell (1972, 1978) called for more information and evaluation regarding K. v. vardonii and K. v. senganus but regarded K. kob and K. vardonii as superspecies. Cotterill (2000) recognized the very close relation between K. kob and “the pukus.” Based on his species definition he considered K. vardonii and K. senganus as two evolutionary species, separating along the Muchinga Escarpment in Zambia. He pointed out that the taxonomic status of the populations in Rukwa and Kilombero valleys, Tanzania, is still unclear ( Cotterill 2000, 2003); these populations were attributed to senganus by Swynnerton and Hayman (1951). Castelló (2016) presented two subspecies K. v. vardonii and K. v. senganus .

Molecular data based on mitochondrial DNA genotypes of the control region and of cytochrome- b ( Cytb) revealed K. vardonii as paraphyletic, a highly differentiated lineage, within populations of K. kob ; further analyses involving nuclear genes are needed for a better understanding (Birungi and Arctander 2000, 2001). Groves and Grubb (2011), whose conclusions are based on the application of the Phylogenetic Species Concept, proposed a revised taxonomy for the K. kob group: they approved K. vardonii as a full species and assigned former subspecies of K. kob as species (i.e., K. kob , K. loderi , K. thomasi , and K. leucotis ).

The most currently accepted authorities and reference works consider K. vardonii a separate and monotypic species (Skinner and Chimimba 2005; Groves and Grubb 2011; Huffmann 2011; Jenkins 2013; IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group 2016).

Kobus vardonii View in CoL is also known as the puku (English, French, German). This name is derived from the local name, which Livingstone (1857) presented as “poku” in his journals. The Setswana name for the species is phuku (Skinner and Chimimba 2005). Other local name are Nsebula (Bemba, Kaonde), Nseula (Nyanja), Hichinsusu ( Tonga), Mutinya (Lozi), Chila, Kampala (Luvale), Nchila (Luanda), Chihunu (Nkoya), Sichisunu (Ila— Ansell 1978), Impookoo (Masubias— Selous 1881). Other vernacular names refer to the scientific name, e.g., Vardon’s kob ( Castelló 2016) View in CoL or cobe de Vardon (French) or to a name based on physical description: Gelbfüssige Moorantilope ( Matschie 1895) in German, translation would be “yellow-footed swamp antelope.”

DIAGNOSIS

Kobus vardonii is sympatric across much of its geographic range with the K. ellipsiprymnus (Ellipsen waterbuck) and K. defassa (Defassa waterbuck). In some areas K. vardonii occurs together with K. leche (red lechwe— Jenkins 2013). K. vardonii (shoulder height 77–94 cm) is considerably smaller than the waterbucks ( 120–136 cm —measurements from Huffmann 2011). In contrast to the dark gray color of the waterbucks, K. vardonii is golden-yellow and it lacks the white rump ring or patch of the waterbucks ( Ansell 1972; Jenkins 2013). Compared to K. leche (shoulder height 87–112 cm — Huffmann 2011), K. vardonii is only slightly smaller, the overall body color is similar, but it lacks the black bands on the forelegs and the horns are shorter (Skinner and Chimimba 2005; Jenkins 2013), horn length is 36–56.2 cm in K. vardonii (see “General Characters”) and 45–66 cm in K. leche ( Castelló 2016) . K. vardonii is very similar to other members of the K. kob group, “the kobs” (especially K. loderi [Loder’s kob], K. thomasi [ Uganda kob], and most especially K. kob [Buffon’s kob]), but they live in allopatry ( Jenkins 2013). K. vardonii differs, however, from the kobs by its heavier proportions, and shorter ( 48–61.6 cm in other members of the K. kob group— Huffmann 2011), thicker, less lyrate horns with less stem ( Kingdon 1982). Its forelegs are missing the black stripes present in the kobs, the premaxilla is not in contact with the nasal ( Ansell 1972), and it possesses active facial glands, a feature that is only poorly developed in the kobs ( Jenkins 2013). The suggested difference between the kobs and K. vardonii in the structure of the inguinal glands ( Ansell 1960b) does not appear to hold for all individuals ( Ansell 1972).

In parts of its range K. vardonii occurs sympatrically with Aepyceros melampus (common impala). The common impala has a similar body color but is lighter in build (shoulder height: 86–98 cm, weight: 43–64 kg — Jarman 2011) and has characteristic black markings on the head, rump, and legs. K. vardonii is sometimes confused with Redunca arundinum (common reedbuck); however, the latter is slightly larger (shoulder height: 65–150 cm), has a different form of the horns (concave curvature), black stripes on the forelegs, and a very bushy tail ( Huffmann 2011).

GENERAL CHARACTERS

Kobus vardonii is a medium-sized antelope and sexually dimorphic. The somewhat rough pelage has an overall goldenyellow coloration on the upper parts of the body, the tail, and the outside of the limbs, whereas the sides of the neck are slightly lighter ( Fig. 1 View Fig ). The underparts and the inner side of the upper part of the limbs are white, as is the upper lip, the throat, the chin, the area around the eyes, the inside of the ears, and a faint band above the hooves, only present in some individuals (Skinner and Chimimba 2005; Groves and Grubb 2011; Huffmann 2011). The tail has a black tip. The black tip of the ears can cover one-third of the external ear surface in some individuals ( Huffmann 2011). The amount of black is proposed as a character to distinguish possible taxonomic groups or subspecies within K. vardonii ( Ansell 1960c; Castelló 2016). The forehead tends to be browner than the rest of the body. The body hairs have a mean length of 32 mm, are large and oblong in cross-section, and present an irregular wavy scale pattern along the entire length of the hair (Skinner and Chimimba 2005). In territorial males, active preorbital glands are associated with a small tuft of black hair and a dark patch on the lower sides of the neck. These patches result from the deposition of the greasy secretion of the glands ( Rosser 1990; Huffmann 2011; see “Reproductive behavior”).

The males of K. vardonii are generally larger and heavier than females and only the males carry horns. External measurements (cm) summarized by Huffmann (2011) were: head–body length 126–156; shoulder height 77–94; and tail length 28–32. Mean external measurements (mm; range and n in parenthesis) for males and females, respectively, from Zambia were: total length 168.1 (158.0–174.0, 5) and 160.2 (154.5–174.0, 6); head–body length 139.8 (129.5–146.0, 5) and 131.1 (126.0–142.0, 6); tail length 28.3 (27.0–29.0, 5) and 29.1 (26.5–32.0, 6); hindfoot cum unguis 41.9 (41.0–44.0, 5) and 40.1 (37.5–42.0, 6); length of ear 15.3 (14.5–15.9, 5) and 14.5 (13.5–15.1, 6); shoulder height 80.9 (80.0–81.5, 4) and 77.8 (73.5–83.0, 6—Skinner and Chimimba 2005). From Luangwa Valley in Zambia, mean external measurements (mm; n in parenthesis) for males and females, respectively, were: total length 146.7 (17) and 133.7 (27); shoulder height 92.1 (17) and 83.7 (27—Skinner and Chimimba 2005).

Mean body weight (kg, with range) is summarized as 77 (67–91) for males and 66 (48–78) for females ( Kingdon 1982). Values of mean body weight (kg; range and n in parenthesis) for Zambia were: males 73.8 (67.5–77.5, 3) and females 61.2 (47.6– 77.9, 5). From Luangwa Valley in Zambia, mean body weight (kg, n) of males was 77.3 (17) and of females 61.3 (27—Skinner and Chimimba 2005).

Cranial measurements (mm; ranges, n in parenthesis) of male and female K. vardonii , respectively, from different locations throughout its geographic distribution were: greatest length 303.00–303.00 (2) and 271–290 (13); condylobasal length 282–286 (2) and 261–278 (12); greatest breadth 112–119 (3) and 98–112 (12); nasal length 97–129 (4) and 92–120 (12); nasal breadth 23.5–33 (4) and 20–30 (12); maxillary teeth length 73–75 (4) and 65–78 (13—Groves and Grubb 2011).

The horns are lyre-shaped and stout ( Fig. 2 View Fig ). The horns run backwards after a relatively small vertical rise from the skull. They are heavily ridged for the basal two-thirds or threequarters of their length and smooth toward the tips (Skinner and Chimimba 2005; Huffmann 2011). Horn length is given variously ( n, if available, in parenthesis), as 400–540 mm ( Kingdon 1982) or as horn length curve 360–480 mm (5) and horn length straight 302–378 mm (5—Groves and Grubb 2011). The longest horns, 562 mm, are reported from Luangwa Valley (Skinner and Chimimba 2005; Jenkins 2013).

DISTRIBUTION

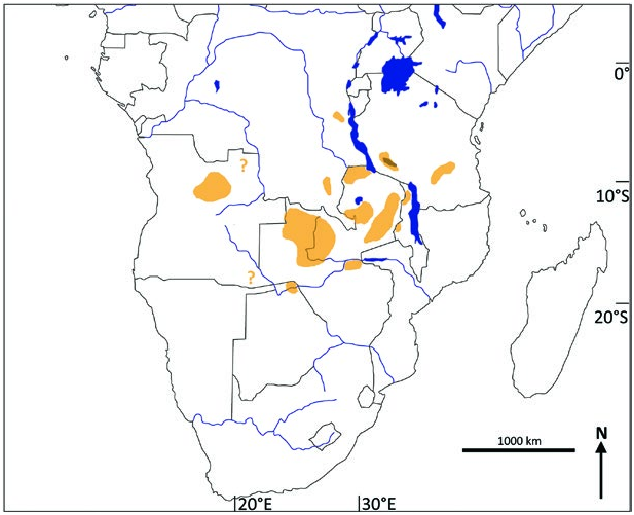

Kobus vardonii is endemic to south-central Africa ( Fig. 3 View Fig ) where it formerly had a wide occurrence. The current distribution is caused by the fragmentation of a once interconnected network of populations associated with major river valleys ( Jenkins 2013). Eliminated from large parts of its former range, K. vardonii is now reduced to isolated populations. Although some populations, especially in Tanzania and Zambia, are still numerous ( East 1999; International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources SSC Antelope Specialist Group 2016). In Tanzania, the Kilombero Valley supports the largest population comprising at least 50% of all animals, most of them occurring in the Kilombero Game Controlled area, only a few in the bordering Selous Game Reserve. A small population still occurs at Lake Rukwa but the population at the northern end of Lake Malawi has been exterminated (Rodgers and Swai 1988; East 1999; Jenkins 2013). Although the total population numbers are lower for Zambia, encompassing about 30% of all K. vardonii ( East 1999) , this country can be considered the center of its distribution. Formerly K. vardonii was widespread in Zambia, absent however, from the extreme west, most of the Southern Province plateau, the middle Zambezi Valley, the Lukasashi and Luano valleys, and the Eastern Province plateau ( Ansell 1972). Around 85% of the Zambian population of K. vardonii occurs in protected areas (International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources SSC Antelope Specialist Group 2016), where it is still common, especially in Luangwa Valley, Kafue National Park, Nsumbu National Park, and Tondwa Game Management Area. Smaller populations occur in Kasanka National Park, West Lunga, and Mweru Wantipa National Park and some other Game Management Areas ( East 1999; Jenkins 2013). K. vardonii was once widespread in central and northern Malawi, currently only small populations remain in Kasungu a common ancestral stock in the Plio-Pleistocene (Birungi and Arctander 2000). Cytb data indicate a divergence of K. vardonii and K. kob approximately 150,000 years ago, which is confirmed by paleontological findings (Birungi und Arctander 2001).

National Park and Vwaza Marsh Game Reserve, with vagrants occurring in Nyika National Park ( East 1999). In the Congo ( DRC), K. vardonii once occurred in Upemba National Park in the southeast ( Jenkins 2013), but also in the Kwango District in the southwest ( Ansell 1972). Today it occurs in unknown numbers in few localities like Kundelungu National Park and perhaps in the Luama Hunting Zone ( East 1999; Jenkins 2013). There is no reliable information from northeast Angola where K. vardonii was once widespread but may have been greatly reduced. A small population lives in Luando Reserve ( Jenkins 2013). In the protected areas of the middle Zambezi Valley in Zimbabwe, K. vardonii is reported as a vagrant. In Namibia it is found on communal land in the Eastern Caprivi. Botswana holds the southernmost population which was once numerous along the Chobe (Linyanti) River, but today only a small population prevails in Chobe National Park ( East 1999; Dipotso and Skarpe 2006).

FOSSIL RECORD

The first representatives of Reduncini appeared in the late Miocene ( Gentry 1990, 2010). Today this taxon is confined to Africa ( Gentry 1978). However, they appear in Africa in the Lukeino Formation and Mpesida Beds of Kenya, in the Siwalik Hills of India ( Gentry 2010), and also from North Africa to the Levant ( Bibi 2011). They continue in the Pinjor Formation of the Upper Siwaliks ( Gentry 1990). Reduncini contain two living genera Redunca and Kobus and a third main fossil lineage Menelikia , which survived until the late Pliocene or just into the Pleistocene ( Gentry 2010). Kobus kob is known in the fossil record to have occurred since about 3.0 million years ago ( Gentry 1990). Fossil deposits of K. vardonii are not known to exist until after the early Pleistocene. K. kob and K. vardonii share

FORM AND FUNCTION

Kobus vardonii has active facial glands. The preorbital gland is just a small piece of thickened glandular skin. Externally visible is a small area of darkened hairs. Internally, it is subcircular, about 10–15 mm in diameter, with hair follicles visible. The secretion of these glands is slightly sticky and smells sweet and not unpleasant ( Ansell 1960b). In territorial males the secretion is transferred by grooming onto the thickened neck musculature. The resulting neckpatch acts as a visual and probably olfactory signal to advertise territorial status and to highlight the neck and thus the individual’s fighting ability ( Rosser 1990). The inguinal glands are situated in inguinal pouches. These glands produce a light yellow and waxy substance which smells strong and unpleasant ( Ansell 1960b). In adults the inguinal pouches are 40–80 mm deep. The external opening is 20–25 mm in females and 9–11 mm in males. In females the openings are situated at a level about midway between the anterior and posterior mammae, whereas in males they are situated almost in line or behind the level of the posterior vestigial mammae. In both sexes the pouches converge posteriorly, so that the posterior edges almost touch ( Ansell 1960b). K. vardonii also has a vestigial duct of a pedal gland; it appears as a minute orifice, in a shallow interdigital cleft ( Ansell 1960b).

The stomach of K. vardonii is characterized by a large and subdivided ruminoreticulum, with strong pillars devoid of definite papillae and unevenly distributed ruminal papillar with concentration at mid-level and in sacks and niches. A medium-sized reticulum and a large omasum with numerous leaves of several orders, that means several magnitudes, are present. The rumen capacity is around 6 liters (Stafford and Stafford 1990).

The dental formula of K. vardonii is i 0/3, c 0/1, p 3/3, m 3/3, total 32 ( Huffmann 2011). It possesses two pairs of inguinal mammae ( Ansell 1960a). Sense of smell appears to be poorly developed in K. vardonii (de Vos and Dowsett 1964) .

ONTOGENY AND REPRODUCTION

Ontogeny. —The pelage of a fetal specimen (about 1–2 days before birth) of Kobus vardonii had a distinct black line (about 5–10 mm in width) on each side of its body. The lines occurred in the area where the dorsal body color met the ventral white. The lines started about 40 mm apart in the area of the forelimbs and continued posteriorly until the start of the groin. It was about 5–10 mm in width. Similar markings were traceable in juveniles but absent in adults ( Ansell 1960b). A single body weight of 5.8 kg has been measured for a young individual 3 days postpartum ( Rosser 1987 [not seen, cited in Skinner and Chimimba 2005:687]). After birth, the young remain hidden for a few weeks in long grass away from adult animals ( Ansell 1960a; Dipotso and Skarpe 2006). Calves are weaned at 6 ( Castelló 2016) or 7 months ( Jenkins 2013). K. vardonii reaches sexual maturity at 12–14 months ( Castelló 2016). Females (67% of marked individuals) may be capable of conceiving as yearlings ( Rosser 1987 [not seen, cited in Skinner and Chimimba 2005:687]). The minimum body size needed for male K. vardonii to achieve breeding status is assumed to be equivalent to two linear measurements of the smallest territorial male, that is, a body length of 142 cm and a shoulder height of 87 cm ( Rosser 1990). Among potential breeding males, territorial males differ from bachelors by physical characteristics and behavior, namely a thickened neck musculature advertised by a seasonal neckpatch and the utterance of bouts of whistles ( Rosser 1990).

Reproduction. —The length of the estrous cycle is 19–21 days ( n = 4) and estrous behavior rarely lasts more than 24 h ( Rosser 1987 [not seen, cited in Skinner and Chimimba 2005:687). K. vardonii has an estimated gestation length of 8 months ( Rosser 1989). A postpartum estrous is possible but usually occurs after 3–4 months (Skinner and Chimimba 2005). Litter size is one young per birth ( Ansell 1960a). K. vardonii breeds year-round with calves recorded in all months (Dipotso and Skarpe 2006; Huffmann 2011). There are, however, breeding peaks that vary between regions and also between years ( Rosser 1989; Dipotso and Skarpe 2006). In Chobe National Park, Botswana, most of the young are born from January to June, in the late rainy and early dry season (Dipotso and Skarpe 2006). On the northwestern plateau of Zambia, Ansell (1960a, 1960c) suggested the main birth season occurs from May to September but emphasized the need for more data. In the Luangwa Valley, Zambia, the peak in births probably starts in January ( Rosser 1989). The majority (68%) of the births took place in the wet season months, January–April. Most of the remaining births (32%) were recorded in the cool dry season; a possible secondary peak of births is suggested in June and July. Of 29 calves that were born to known females, none were born in October, November, or December ( Rosser 1989). In Kasanka National Park, Zambia, most of the young reached two-thirds adult body size by July ( Goldspink et al. 1998). The peak of conceptions was from May to June, which was predicted from a birth peak period from February to March ( Rosser 1989). The interval between births is about 390 days ( Rosser 1989). K. vardonii has a high reproduction rate; one year’s reproductive output per 100 adult females was 78 calves (Dipotso and Skarpe 2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Kobus vardonii ( Livingstone, 1857 )

| Rduch, Vera 2020 |

Kobus vardonii senganus :

| GRUBB, P. 2005: 721 |

Kobus vardonii vardonii : Grubb, 2005:721

| GRUBB, P. 2005: 721 |

Kobus senganus : Cotterill, 2000:168

| COTTERILL, F. P. D. 2000: 168 |

Kobus kob vardoni : Haltenorth, 1963:92

| HALTENORTH, T. 1963: 92 |

Kobus kob senganus : Haltenorth, 1963:92

| HALTENORTH, T. 1963: 92 |

Kobus vardonii :

| BEST, G. A. & EDMOND-BLANC, R. 1962: 83 |

Cobus senganus

| MOREAU, R. E. 1946: 437 |

Adenota vardonii vardonii :

| ALLEN, G. M. 1939: 511 |

Adenota vardonii senganus

| ALLEN, G. M. 1939: 511 |

Cobus vardoni typicus :

| SELOUS, F. C. 1899: 294 |

Cobus vardoni senganus : Bryden, 1899: 299

| BRYDEN, H. A. 1899: 299 |

Adenota vardoni :

| MATSCHIE, P. 1895: 126 |

Eleotragus

| HUET, M. 1887: 83 |

Cobus vardoni :

| SELOUS, F. C. 1881: 759 |

Heleotragus vardonii :

| KIRK, J. 1864: 657 |

Antilope Vardonii

| MOREAU, R. E. 1946: 437 |

| LIVINGSTONE, D. 1857: 256 |