Cheleion malayanum, Vårdal & Forshage, 2010

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.3897/zookeys.34.264 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:4E78321B-96D8-4C57-A3C5-79E38C713F4E |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3789788 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/D8732C0E-4747-4276-8F27-2354509159F3 |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:D8732C0E-4747-4276-8F27-2354509159F3 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Cheleion malayanum |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Cheleion malayanum sp. n.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:D8732C0E-4747-4276-8F27-2354509159F3

Material. Holotype: Malaysia, Pahang, Bukit Frazer, 1200 m, 7-9/4 – 1992, Malaisetrap in jungle, Heikki Hippa leg. Swedish Museum of Natural History ( NHRS).

Etymology. The first specimen of the species was collected in Malaysia.

Diagnostic characters. Structures such as the hastate posterior prosternal process, pattern on the pronotum with a strong anteromedial knob as well as bulbous areas medially and laterally on each side at the posterior end of the pronotum, the very long antennae and the strongly tuberculate and rugose surface of the body will easily separate this species from other known Stereomerini .

Description. Length 1.8 mm, width at broadest point 0.9 mm. Chestnut brown, whole body rather densely covered with strong puncture; strongly convex. Morphology as in generic description and as in Figures 1–6.

Phylogenetic estimate

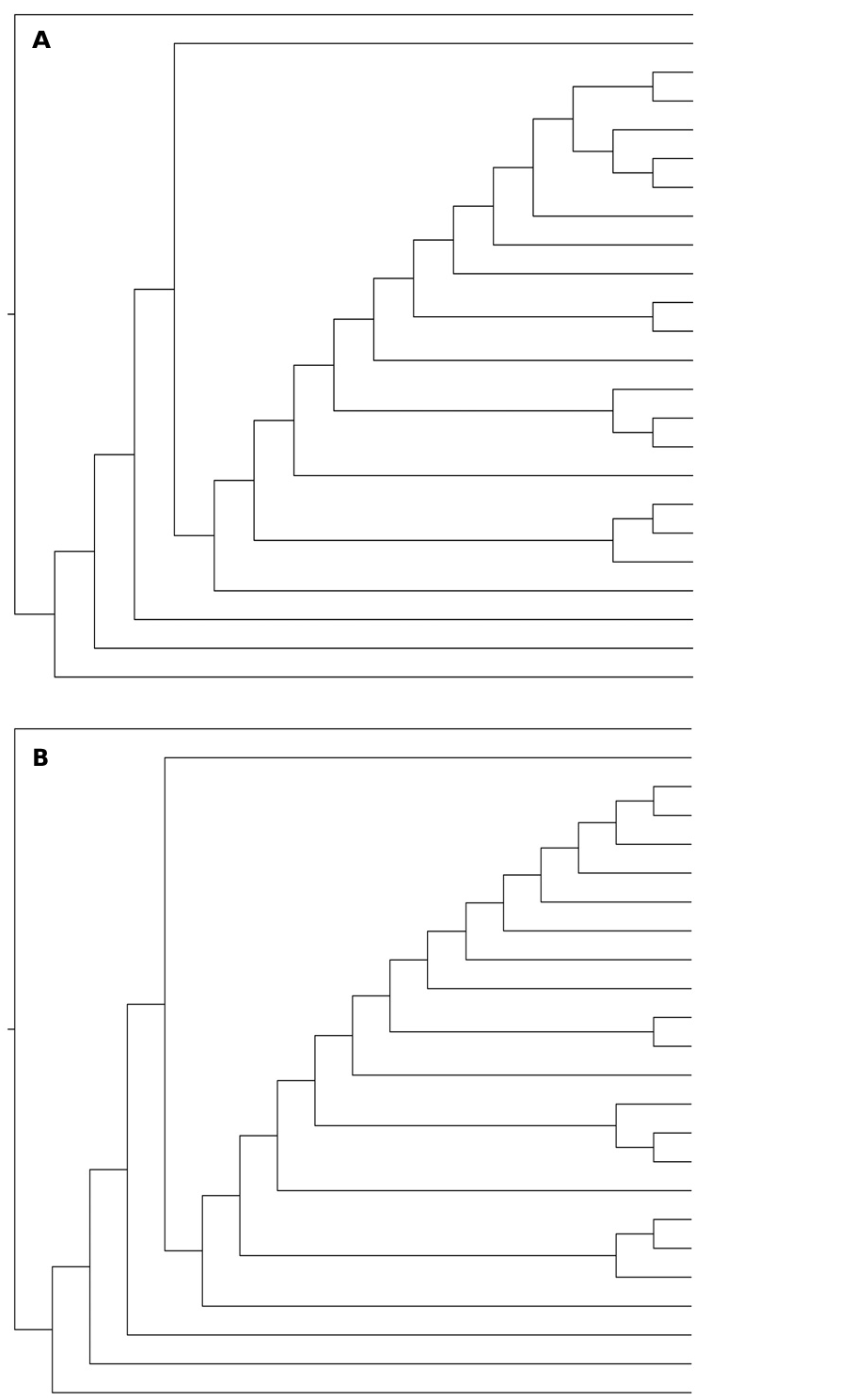

The three resulting most parsimonious trees ( Figure 7 View Figure 7 A-C) differ only in the internal relationships within the Steremerini genera Australoxenella , Bruneixenus , Pseudostereomera , Stereomera and Adebrattia (as shown in the consensus tree, Figure 7D View Figure 7 ). The rest of the Stereomerini species, namely the new taxon, Danielssonia and Daintreeola appear in the same positions in all three trees ( Figure 7 View Figure 7 A-C). None of the three configurations corresponds very well with Bordat and Howden’s (1995) cladogram (we do not compare with Storey and Howden as they only included three representatives of

Figure |. Dorsal view of Cheleion malayanum sp. n. A scanning electron micrograph B stereo microscope image.

Stereomerini in their 1992 analysis) in which the sister species Adebrattia-Bruneixenus forms a sister group to Danielssonia-Australoxenella- (Stereomera-Pseudostereomera). One reason for this may be that neither the new taxon nor Daintreeola were included in the Bordat and Howden (1995) analysis. Our results rather points to a close relationship between Adebrattia and Pseudostereomera and between Australoxenella and Bruneixenus . Stereomera was placed as a sister group to the Adebrattia-Pseudostereomera in 2 of the 3 trees and as sister group to Australoxenella-Bruneixenus in the third tree.

Concerning the relationships outside Stereomerini , our results point to a close relationship between Stereomerini and the genus Termitaxis , that was formerly included in Stereomerini but is now considered incertae sedis ( Bordat and Howden 1995), and the Termitotrogini ( Termitotrox ). Corythoderini appears monophyletic, as does a core of Rhyparini (if excluding Sybacodes , the position of which has been ambiguous, and Cartwrightia , previously classified in Eupariini and recently transferred to Rhyparini). All representatives of the aberrant tribes form a monophyletic group together, while the more typical Eupariini genera form a grade basal to this group.

Discussion

History of classification of inquiline Aphodiinae

There are several taxa in Aphodiinae which have inquiline or inquiline-like morphologies (listed in Table 4). They are usually small, have integumental bulbs and ridges, particularly longitudinal dorsal ridges; sometimes contracted body shapes; short, broad extremities, sometimes less so; and occasionally hair tufts or inflated abdomen. Their classification has included some moments of confusion.

In the first tribal division of Aphodiinae ( Schmidt 1910) , all the termitophilic or termitophile-like species were classified as Rhyparini and Corythoderini (only later were Termitotrox considered to be part of or closely related to Aphodiinae ).

Termitoderini was added explicitly as a probable sister group to Corythoderini ( Tangelder and Krikken 1982), and Stereomerini in a similar way as the sister group to Rhyparini ( Howden and Storey 1992). The boundaries between all these tribes have been somewhat confused due to the uncertain status of some genera, and to the citing of all recent or problematic taxa as Termitoderini in Dellacasa’s catalogue ( Dellacasa 1987 –88).

Termitoderini was erected as monotypic, but Dellacasa listed six genera there (including several from Rhyparini), which may have been a mere mistake, or a conscious reclassification with no arguments presented in the series of corrigenda to the cata- logue. The genera that actually belonged to Ceratocanthidae were deleted (“dropped”) but no further information given on the others ( Dellacasa 1991).

If disconsidering Dellacasa’s classification, it becomes rather straightforward: Termitaxis was described in Rhyparini ( Krikken 1970) but removed to become incertae sedis ( Howden and Bordat 1995), Cartwrightia was classified as Eupariini , but transferred to Rhyparini ( Galante et al. 2003; Stebnicka 2009), Sybacodes were always considered Rhyparini but it has been questioned ( Howden and Bordat 1995), Notocaulus were classified as Rhyparini, but transferred to Eupariini ( Krikken and Huijbregts 1987; Howden and Storey 1992).

A number of more or less aberrant genera have been added to the Rhyparini in recent years ( Howden 1995, 2003; Howden and Storey 2000; Makhan 2006; Pittino 2006), with Skelley (2007) making an effort to straighten up the classification and listing several papers describing new species or otherwise forwarding knowledge which are not listed here. Krikken (2008a, b) recently reconsidered and described new species in Termitoderini and Termitotrogini.

In addition to these, a number of ant inquilines have always been present in the Eupariini , including the type genus Euparia , and two species which are termite inquilines. At one point, Stebnicka erected the tribe Lomanoxiini for the most aberrant Neotropical ant inquilines ( Stebnicka 1999), but that was synonymized into Eupariini ( Skelley and Howden 2003) . All these Neotropical forms were recently reviewed and pictured in Stebnicka (2009).

Adebrattia depressa Pseudostereomera mirabilis Australoxenella humptydooensis Brunixenus squamosus Stereomera pusilla

New taxon

Danielssonia minuta Daintreeola grovei

Termitaxis holmgreni Termitotrox consobrinus Sybacodes simplicicollis Rhuparus suturalis Termitodiellus esakii Termitodius peregrinus Cartwrightia intertribalis Corythoderus loripes Neochaetopisthes heimi Termitoderus ultimus Notocaulus sculpturatus Ataenius scabrelloides Saprosites laeviceps

Adebrattia depressa Pseudostereomera mirabilis Stereomera pusilla

Bruneixenus squamosus Australoxenella humptydooensis New taxon

Danielssonia minuta Daintreeola grovei

Termitaxis holmgreni Termitotrox consobrinus Sybacodes simplicicollis Phyparus suturalis Termitodiellus esakii Termitodius peregrinus Cartwrightia intertribalis Corythoderus loripes Neochaetopisthes heimi Termitoderus ultimus Notocaulus sculpturatus Aphodius elegans

Adebrattia deprssa Pseudostereomera mirabilis Stereomera pusilla Australoxenella humptydooensis Bruneixenus squamosus

New taxon

Danielssomnia minuta Daintreeola grovei

Termitaxis holmgreni Termitotrox consobrinus Sybacodes simplicicollis Rhyparus suturalis

Termitodius peregrinus Cartwrightia intertribalis Crithoderus loripes Neochaetopisthes heimi Termitoderus ultimus

Stereomerini , Rhyparini, Corythoderini , Termitoderini, Termitotrogini, Aphodiini and Euparini.

The classification, and above all the relationships between the inquiline tribes, remains unsure because of the more or less far-reaching morphological specializations, including both obvious strongly derived specializations in habitus and integument, as well as reductions in characters traditionally used for distinguishing aphodiine tribes. Many of these specializations often overlap between the inquiline tribes, thus obscuring relationships between each other and between them and the large aphodiine tribe Eupariini , which is speciose in the tropics and characterized mainly by plesiomorphies visavis most other tribes of Aphodiinae .

Often, the appearance of tibial ridges and position of tibial apical spurs are used as diagnostic characters between Eupariini and Aphodiini. These characters are often useless in inquiline-type aphodiines with highly modified, short tibiae and reduced spurs. The abdominal characters traditionally used (fusing of sternites, pygidial furrow, etc.) often unite several but not all inquiline-type taxa with most Eupariini . Perhaps the dissection-requiring mouthparts and aedeagus, which both have provided characters considered important for aphodiine classification ( Dellacasa et al. 2001 and elsewhere), but were not studied here, may provide useful information in this respect.

Status of knowledge of biology of alleged inquilines

Strangely enough, it is only some of these inquiline-looking taxa that are actually found in association with social insects. Actually associated with termites are Termitotrogini, Corythoderini , Termitoderini, several small genera in Rhyparini ( Termitodius , Termitodiellus , et al.), plus incertae sedis Termitaxis . One genus of similar morphology ( Cartwrightia ) and many more genera with more normal appearances are actually associated with ants. In several of the inquiline-type taxa, inquiline lifestyles have never been demonstrated; Stereomerini , a major part of Rhyparini (including Rhyparus ), plus Notocaulus and Sybacodes (and Sybax ). Instead, these are often found in forest litter, Notocaulus and Sybacodes also in dung. Of course, sifting forest litter and various trapping methods (light traps, Malaise traps, flight intercept traps) are far more common collecting methods than actually breaking into termite mounds. Thus, these taxa might be inquilines not yet encountered in their true habitat, or they may not live with social insects.

Typologies of social insect inquilines are from Wasmann (1894, 1903, 1918), who also studied many of these aphodiines, like Kolbe (1909). Balthasar (1963) summarized the knowledge. Later, Wilson (1971) and Kistner (1979, 1982) provided general discussion of inquline types.

The basic division is between symphilic inquilines (those actually cared for by the hosts), and inquilines which are synoeketes (ignored by the hosts) or synechthrans (treated with hostility by the hosts). Morphologically, a symphilic lifestyle is often indicated by particular phenomena as possession of specialized tufts of glandular setae (trichomes) or enlarged abdomen (physogastry). Often, symphilic organisms display some kind of general morphological mimicking of their hosts. Synechtrans on the oth- er hand are usually characterized with a “defensive” morphology, often very compact body (sometimes referred to as “limuloid” body shape, after horseshoe crabs ( Limulus )), with reinforcing ridges and the capacity to withdraw protruding appendages into folds or grooves.

Among the aphodiines, Corythoderini , Termitoderini and Termitaxis clearly correspond to the “symphilic” type (and are indeed found with termites). The clearest examples corresponding to the “synechthran” type are presented by Termitotrogini and Stereomerini (the one found with termites, the other not recognized). The Rhyparini are probably best considered synechthran in general morphology, but less so than Termitotrogini and Stereomerini , and also have symphilic-type trichomes. The typical Rhyparini are not found with termites, and could be described as weakly synechthran in morphology. Within Rhyparini, only the more or less aberrant taxa are actually found among termites, often being intermediate between the weaker synechthran-type and symphilic-type morphologies.

The rationale for classification of inquiline tribes

It is unsatisfactory that this cluster of characters is regarded as an indication of a particular lifestyle in so many taxa where that lifestyle has not been observed. Some of them are commonly collected under circumstances giving no support whatsoever for that assumption. In aphodiine classification, various selections from this cluster are utilized to diagnose several aberrant tribes, while still being assumed to be intimately connected with a particular lifestyle and therefore largely homoplastic, and so not necessarily indicating a relationship between these different tribes while still keeping them together one by one. This is a problematic line of reasoning. A Darwinist framework still rests on interpreting similarities as the result of shared ancestry unless in conflict with other similarities. In this data set, the number of characters is small and the taxon sampling, particularly in various groups of possibly related Eupariini , is limited. For this reason, our results are uncertain and do not form the basis for any confidence in suggesting a revised tribal classification. Indeed the consistency is relatively low, but not extremely low, and there is a small number of most parsimonious trees, indicating that there is a fairly strong signal in the data. The Stereomerini , the core Rhyparini (excluding Sybacodes and Cartwrightia ), and the Corythoderini , are all retained as monophyletic groups without conflict. All the representatives of aberrant taxa form a monophyletic group together.

Again, this is not a strong test, but the possibility that their similarities are to a significant extent due to shared ancestry rather than just shared lifestyle must be considered, especially since this particular lifestyle has in fact not been observed in so many of them. The aberrant or termitophilous tribes have been suggested to possibly be related to each other in a few works (Nikolajev 1993; Forshage 2002). Nikolajev suggests they could be related to each other and to Aulonocnemini. The phylogenetic status of Aulonocnemini is not well investigated, and it too might prove to be near or in Eupariini .

The few representatives of Eupariini included, on the other hand, admittedly covering very little of the diversity of the group but nevertheless representing its three most principal genera, did not form a clade together, but instead a grade basal to a single clade of all the “termitophilic” tribes. Eupariini is historically delineated in contrast with Aphodiini, and most of its diagnostic characters are defined in that contrast. As the phylogeny of Aphodiinae remains uncertain, the polarity of most of these characters is not known. Regardless of whether the character states found in Eupariini are plesiomorphic or apomorphic visavis Aphodiini, they are either shared with or clearly plesiomorphic visavis Psammodiini and most minor tribes. In fact it seems impossible to circumscribe Eupariini as a monophyletic group. Eupariini may perhaps be a paraphyletic grade of basal groups of Aphodiini, or it may be a huge possibly monophyletic complex, but in both cases very possibly with Psammodiini and several smaller tribes intermixed.

A more robust phylogenetic analysis including a wealth of eupariine taxa, several of the minor tribes, and many more characters than used here, will highlight the difficuties of keeping Eupariini in its present form, and suggest a revised tribal classification. Whether this will result in the synonymy of several tribes into a solid Eupariini sensu lato, or identify monophyletic lineages that will allow for even further splitting into more tribes, will be up to the judgment of that revisor.

| NHRS |

Swedish Museum of Natural History, Entomology Collections |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Aphodiinae |

|

Tribe |

Stereomerini |

|

Genus |