Psittacula exsul ( Newton, 1872 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1513.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:35934778-7619-4BD0-8D0C-A5817B17EE27 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/243B2E20-FFF4-611F-A086-FA57FB1CFCB7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Psittacula exsul ( Newton, 1872 ) |

| status |

|

Rodrigues parakeet Psittacula exsul ( Newton, 1872) View in CoL

Perroquets verds et bleus, Leguat, 1708: 107.

La seconde espéce [of parrot], text attributed to Tafforet, 1726: 25.

Perruche, Pingré, 1761., in Alby, J., & Serviable, M (eds.) 1993: 45,51.

Palaeornis exsul Newton, 1872: 31 ; Salvadori, 1891: 459; Oustalet, 1896: 14; Rothschild, 1907a: 65.

Psittacula exsul View in CoL ; Peters, 1937: 244.

Holotype: Preserved skin UMZC 18 / Psi /67/h/I female, Rodrigues, 1871 collected by police magistrate George Jenner and originally preserved in spirit.

Measurements: See Appendix 3, tables 1–11..

Type locality: Rodrigues Island, Mascarenes.

Distribution: Rodrigues Island, Mascarenes.

Etymology: From Latin exsul meaning an exile, a banished person.

Paratype: Preserved skin (originally in alcohol) UMZC 18 / Psi /67/h/ 2 male, Rodrigues, 1874 ( Fig. 21 View FIGURE 21 ) .

Referred material: Mandible (removed from holotype) UMZC 564 ; sternum (removed from holotype)

UMZC 564(p). Subfossil material collected by George Jenner, Graham Cowles and the author from the Plaine Corail caverns, Rodrigues: palatine FLMR (L); sternum UMZC 997; pelvis BMNH Rod1(p); furcula UMZC 997; coracoid UMZC 997(R); UMZC 997(L); BMNH A1463(L); BMNH A1463(Ld); scapula UMZC 997(R); UMZC 997(L); humerus BMNH A1463(L); BMNH A1463(R); FLMR R166 (L); ulna BMNH Rod1(R); FLMR R206 (R); femur BMNH A1463(L); BMNH A1463(L); tibiotarsus BMNH A1463(R); BMNH A1463(R); (u/cR).

Diagnosis: Differs from all other Mascarene Psittacula parrots by the following suite of characters mandible: when viewed in dorsal aspect, the internal margin of symphysis oval, not square-shaped. Humerus: proximal end proportionally less expanded than in Psittacula bensoni or P. echo . Coracoid: processus procoracoideus reduced with a shallow cotyla scapularis; a small raised ridge distal to angulus medialis forms a square-shaped lateral edge; proximal to facies articularis clavicularis, a foramen pneumaticum present but not markedly excavated or pneumaticized. Femur: distinct impressiones obturatoriae with deep excavation distal to the trochanter. The Rodrigues parakeet exhibits osteological characters that suggest a close relationship with other Mascarene species of Psittacula , which is particularly evident in the comparatively reduced sternum with an anterodorsal projection of the spina externa and the pelvic elements proportionally robust.

Description and comparison: See Appendix 2d.

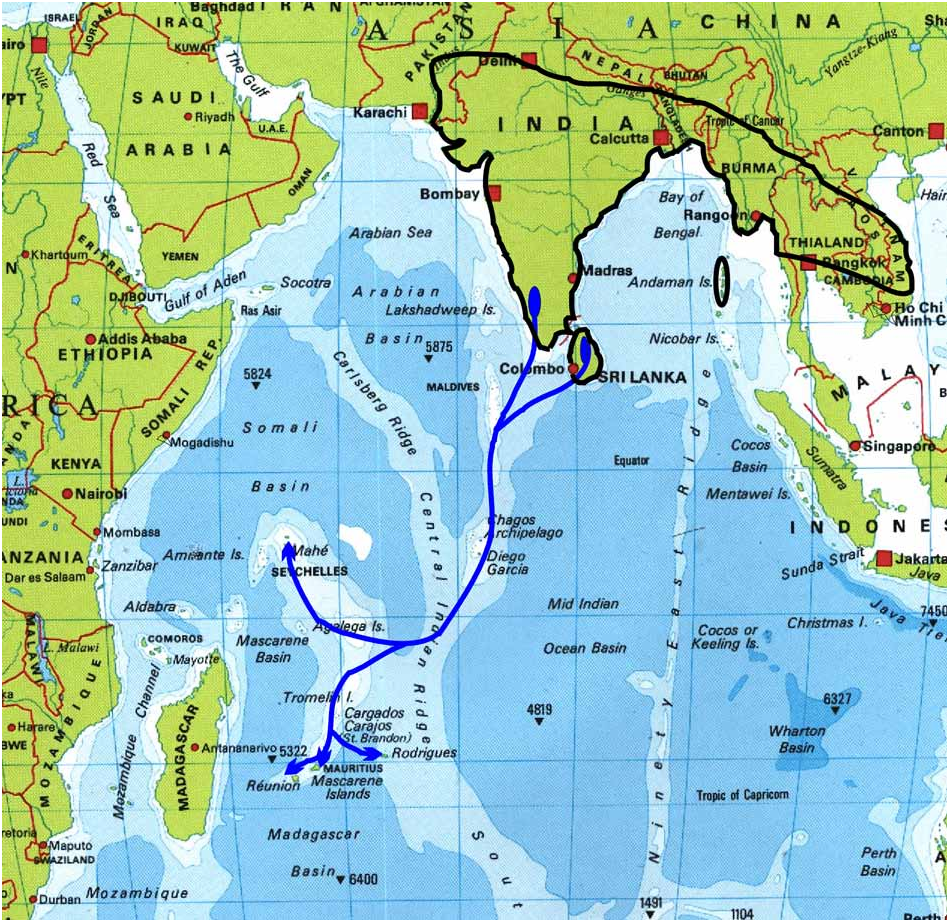

Remarks: It has been suggested that Psittacula eupatria may be the founding species for all species of Psittacula that occur on islands in the Indian Ocean. These species tend to lose characters of P. eupatria , including reduction in size, as one progresses southward ( Smith 1975; Jones 1987). The present day distribution of P. eupatria includes India and parts of Southeast Asia ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 ) and southward colonisation appears to have given rise to the parrots of the islands of the Indian Ocean (see Discussion). Skeletal morphology further supports a close relationship between P. exsul and P. eupatria , but the derived nature of P. exsul suggests that it has long been on Rodrigues.

Leguat (1708) briefly described parakeets during his stay on Rodrigues and commented on their partiality to the nuts of Bois d’olive Cassine orientale . He took a living bird that had been taught to speak French and Flemish with him to Mauritius (see below). Leguat’s account of the Rodrigues parakeet also opened a historical conundrum that has not been satisfactorily resolved ( Grant 1801; Newton 1872; Newton & Newton 1876):

There are abundance of green and blew Parrets, they are of a midling and equal bigness; when they are young, their Flesh is as good as young Pigeons [ Leguat 1708: 77].

Leguat’s account suggests either that there were green parrots and blue parrots of the same size (possibly referring to Necropsittacus rodericanus and Psittacula exsul ), or that he was describing colour variations of Psittacula exsul . The two surviving skins are blue ( Fig.21 View FIGURE 21 ), but in the original description by Newton (1872), which may partly explain the contradictory statements (see also the account of the Mascarene parrot, below), he states that the ‘head, nape, shoulders, upper wing-coverts and retrices above dull greyish-glaucous, the blue tinge in which predominates when the bird is seen against the light, and the green when seen in contrary aspect.’ Furthermore, a live specimen was received by the naturalist Philibert Commersen on Mauritius during the 1770s, where it was described as long-tailed, greyish-blue parrot with a black collar ( Oustalet 1897: 11). This individual was illustrated by Jossigny on at least 2 occasions, the only time this species was depicted in life ( Hume & Prys-Jones 2005), and here published for the first time ( Fig. 27 View FIGURE 27 ). Frustratingly for science, a more detailed account by Tafforet in 1726 [ Dupon 1973]) describes a predominantly green P. exsul but fails to mention a blue one:

The parrots are of three kinds, and in quantity……The second species [= ♂ P. exsul ] is slightly smaller and more beautiful, because they have their plumage green like the preceding [ Necropsittacus ], a little more blue, and above the wings a little red as well as their beak. The third species [= ♀ P. exsul ] is small and altogether green, and the beak black [translation from Cheke & Hume in prep.].

Despite the lack of detail, Tafforet’s account is extremely important because he describes the green bird as having a red shoulder patch. The astronomer Abbé Pingré, who visited Rodrigues in 1761 to monitor the Transit of Venus, discussed the fauna in some detail, including parrots. He may have been referring to this character as well:

the perruches I saw at Rodrigues were entirely green, without any [word illegible] of red or other colour [ Cheke 1987: 47].

The red shoulder is found only in Psittacula eupatria but not in P. krameri . In selective breeding by aviculturists, green to blue colour alteration is the most frequent change in psittacines ( Nemésio 2001) and easily produced in Psittacula ( Fig.18 View FIGURE 18 ). Furthermore, the suppression of yellow (which produces the blue colouration) also results in the suppression of red ( Jones 1987; Nemésio 2001), so a blue bird might lack red shoulder patches. As the two skins were originally preserved in alcohol, the blue colouration may have been an artifact of spirit storage with the original green changing to blue, but examination of specimens preserved in alcohol averaging 75 years old ( Psittacula cyanocephala BMNH 1933.3.5.1; P. calthrapae BMNH 1929.7.1.1 and P. alexandri fasciata BMNH 1924.4.7.11) show negligible changes in colour. The greens, which have a carotenoid component, are dull and browner whereas the blues, based on melanin, are unchanged.

The Rodrigues parakeet survived until comparatively recently but the species was in decline from the1760s. Leguat reported it as abundant during his stay in 1691-2, and amused himself with captive birds, primarily because they were too easy to kill:

Hunting and Fishing were so easie to us, that it took away from the Pleasure. We often delighted ourselves in teaching the Parrots to speak, there being vast numbers of them. We carried one to Maurice Isle, which talk’d French and Flemish [ Leguat 1708: 95].

It was still common during Tafforet’s stay in 1726 ( Dupon 1973), but had become rare by the time of Pin gré’s visit in 1761 (see also Necropsittacus below; Alby & Serviable 1993). Like Necropsittacus , however, it still occurred on the southern islets:

On the 19 th [ June 1761] at Isle Mombrani [=Gombrani], the multitude of grey terns on our side [of the boat] served exactly as a parasol; they fly about our heads, in the manner more or less to ease the heat of the sun. In an additional premium to this there were tropic birds and their eggs. There are also some frigates, some tratras [Red-footed Booby Sula sula ], some perruches [ Psittacula exsul ] [my translation].

After the visit of Pingré, Rodrigues suffered severe deforestation and increased land use for free-roaming livestock ( North-Coombes 1971). Government surveyor Thomas Corby was sent to survey Rodrigues in 1843, to ascertain the suitability of the land to support cattle ( North-Coombes 1971: 85). Corby remarked that the western side of the island, although severely deforested, still contained the best stands of palms and vacoas ( Pandanus sp. ). He also mentioned the presence of many wild bullocks, pigs, great flights of guinea fowl and green parrots, indicating that P. exsul must still have been fairly numerous. The first specimen was received by Alfred Newton in 1871 ( Newton 1872), but by this time, the parakeets had become pitifully scarce. The biologist Henry H. Slater stayed on Rodrigues for 3 months during the 1874 Transit of Venus expedition and saw only one parakeet on 30 September in forests on the southwestern side of the island ( Slater 1879a). The assistant colonial secretary William James Caldwell, arriving on 12 May 1875, saw several during his stay of 3 months but failed to obtain a specimen ( Caldwell 1875). He did, however, receive a male of the species from ships’ pilot and local resident William Vandorous on 14 August 1875 ( Newton & Newton 1876). Alfred Newton received this individual at Cambridge, England, and this was the last time the species was recorded. A devastating series of cyclones struck the following year ( North-Coombes 1971), perhaps wiping out the last few survivors ( Cheke 1987). Contrary to Greenway’s (1967) suggestion that P. exsul might survive on offshore islets, the Rodrigues islets are probably too small to support viable populations of birds.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Psittacula exsul ( Newton, 1872 )

| HUME, JULIAN PENDER 2007 |

Psittacula exsul

| Peters, J. L. 1937: 244 |

Palaeornis exsul

| Rothschild, W. 1907: 65 |

| Salvadori, T. 1891: 459 |

| Newton, A. 1872: 31 |