Phaneromerium Verhoeff, 1941

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.5115.3.7 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:F9C7819F-1752-4F28-B5A6-15530B058DA1 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6358469 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BA1D87E1-3355-FFC4-FF0E-FBA1FB5BF8B2 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Phaneromerium Verhoeff, 1941 |

| status |

|

Genus Phaneromerium Verhoeff, 1941 View in CoL

Type species: Cryptogonodesmus obtusangulus Carl, 1914 , from Colombia, by monotypy.

Other species included: P. laticeps (Kraus, 1954), P. longipes (Kraus, 1954), P. minimum (Kraus, 1954), P. robustum (Kraus, 1955), P. taulisense (Kraus, 1954), all from Peru, P. distinctum Golovatch, 1994, P. latum Golovatch, 1994, P. minutum Golovatch, 1994, all three from near Manaus, Brazil, and P. cavernicolum Golovatch & Wytwer, 2004 , from a cave in Bahia, Brazil. All ten species of the genus have been keyed ( Golovatch & Wytwer 2004).

Diagnosis. One of the basalmost genera of Trichopolydesmidae with relatively little enlarged gonopod coxites that form together no considerable gonocoel cavity, but support instead almost fully exposed, suberect and relatively simple telopodites, uni- or bipartite, held parallel to each other ( Golovatch 1994). This condition is deemed to be the most primitive in the gonopodal evolution of Neotropical Trichopolydesmidae compared to the developments observed in the remaining eight genera that occur in the region ( Golovatch 1992, 1994; Golovatch & Wytwer 2004).

Phaneromerium troglopterygotum Golovatch & Gallo , sp. nov.

Figs 4–10 View FIGURE 4 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10

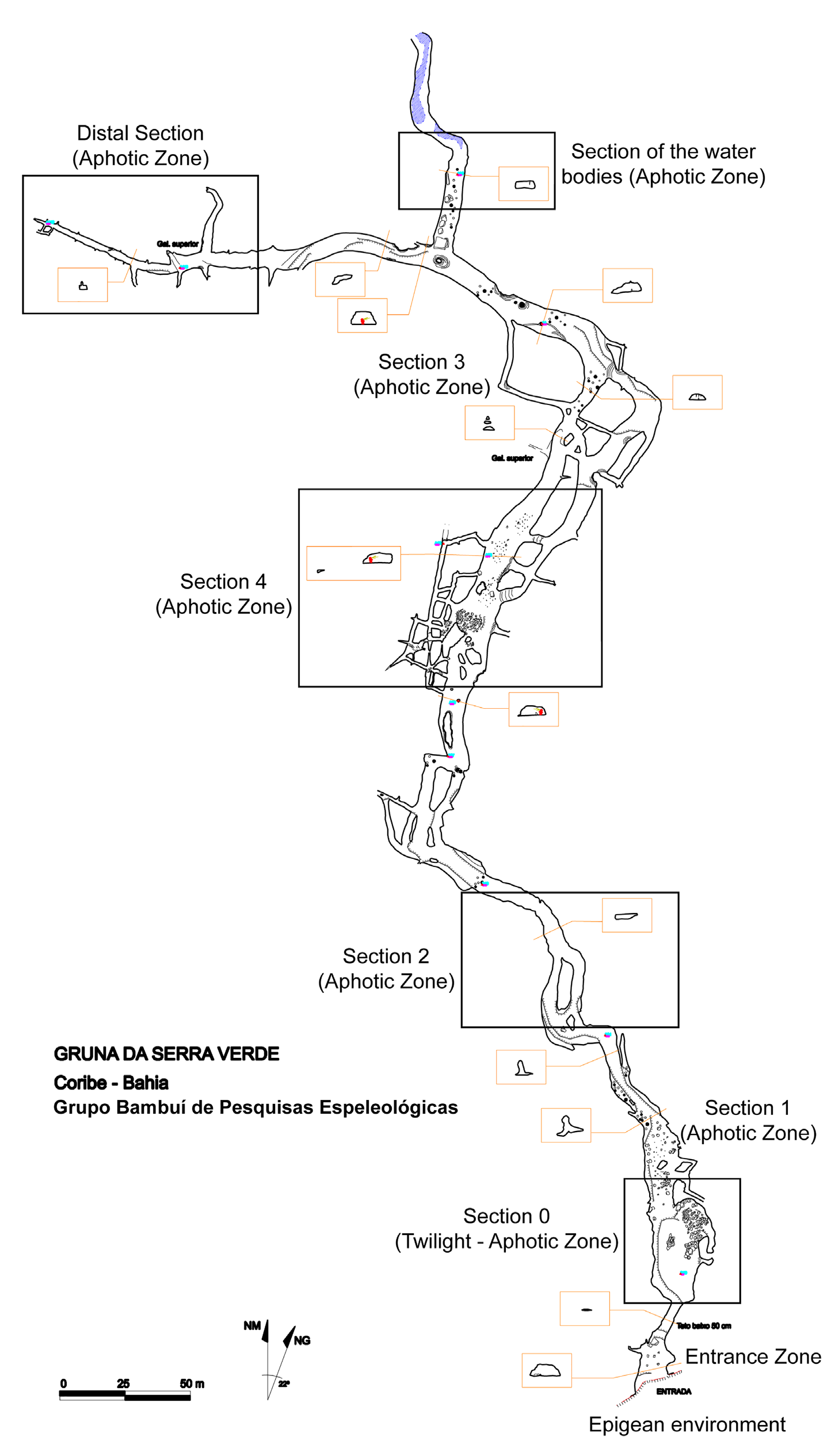

Material examined. Holotype male ( LES 0027861 About LES ), Brazil, Bahia State, Coribe Municipality, Gruna da Serra Verde cave , aphotic zone, S13°43’28.0”, W44°19’26.9”, 05.VII.2021, M.E. Bichuette, J.E. Gallão, J.S. Gallo & V.F. Sperandei leg. GoogleMaps

Paratypes: 1 male, 1 female ( ZMUM) , 3 males, 1 female, 3 juv. (LES 0027862), same locality, taken together with holotype ; 5 males, 2 females (LES 0027863), same locality as holotype GoogleMaps .

Name. To emphasize cave-dwelling, combined with strongly developed and clearly upturned paraterga in adults, the Latinized “troglopterygotum” meaning “caver-and-winged” with Greek roots, neuter in gender.

Diagnosis. Using the latest and still completely pertinent key to Phaneromerium species by Golovatch and Wytwer (2004), P. troglopterygotum sp. nov. keys out to P. cavernicolum , but differs from it and all other congeners by the especially broad, strongly developed and mostly clearly upturned paraterga, coupled with bipartite and slender gonotelopodites, the solenomere being a shorter branch lying mesal to the exomere branch ( Figs 7E, F View FIGURE 7 , 8B, C View FIGURE 8 ). In addition, both species compared are the largest among congeners, presumably troglobionts stemming from the same state of Bahia and sharing all main troglomorphic characters (enlarged and unpigmented body, strongly broadened paraterga, and elongate extremities) except for the tergal setae which are clearly shorter in P. troglopterygotum sp. nov. than in P. cavernicolum . In addition, both sl and ex branches of the gonopodal telopodites are slightly differently shaped in the two species concerned ( Figs 7E, F View FIGURE 7 , 8B, C View FIGURE 8 ).

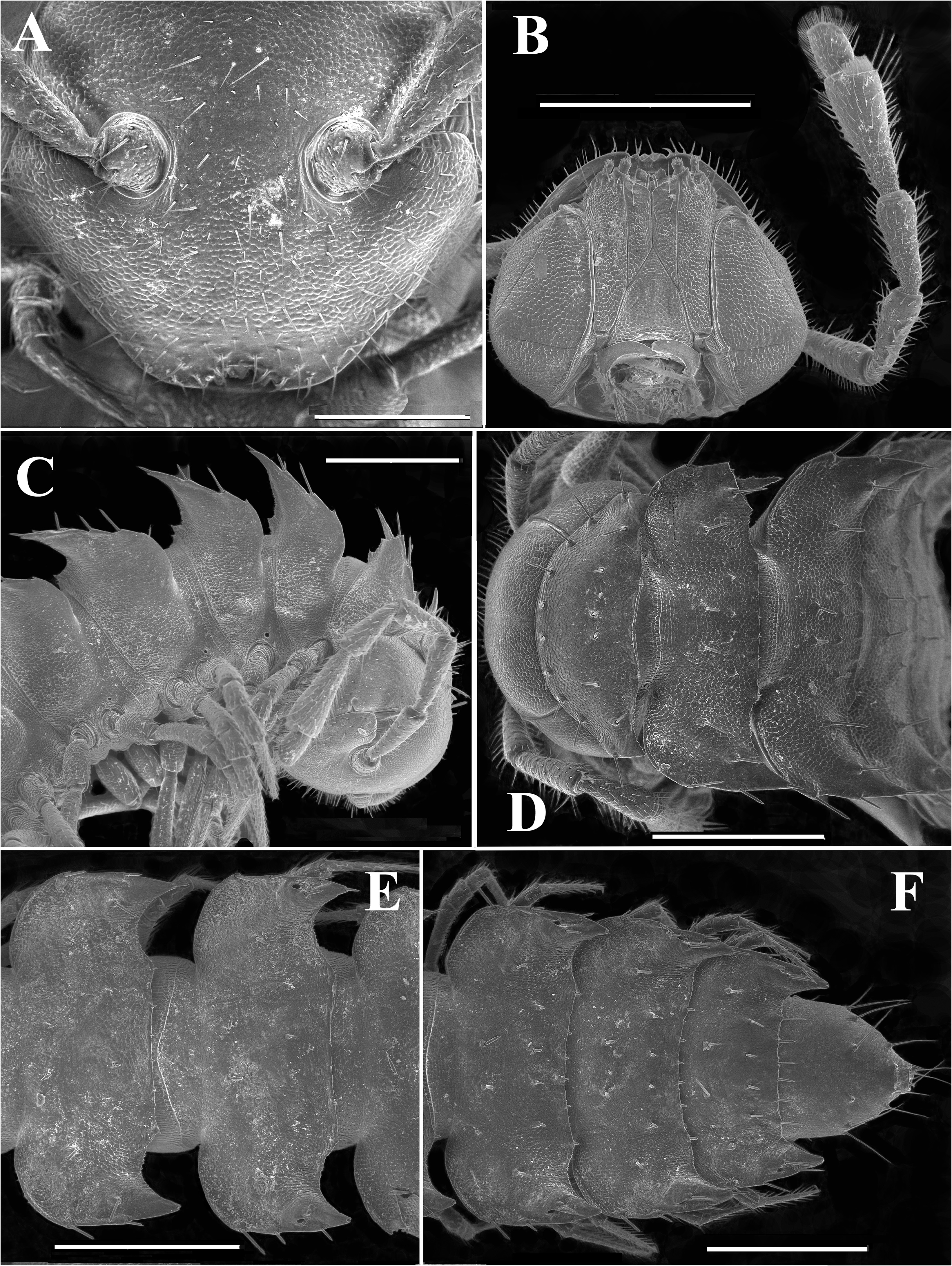

Description. Length of adults ca 9–10 mm, width of midbody pro- and metazonae 0.5–0.7 and 1.0– 1.3 mm (male, female), respectively. Holotype male ca 9 mm long and 0.5 and 1.0 mm wide on midbody pro- and metazonae, respectively. Coloration entirely pallid ( Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5 , 9 View FIGURE 9 ).

Body with 20 rings ( Figs 4A–C View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Tegument mainly dull, at most slightly shining, texture very delicately alveolate and scaly. Head rather densely setose all over clypeolabral region and vertex, epicranial suture faint; isthmus between antennae ca 1.2 times broader than diameter of antennal socket ( Fig. 6A View FIGURE 6 ). Antennae very long and slender, poorly clavate due to only a slightly enlarged antennomere 6, in situ projecting past ring 3 dorsally (male, female); in length, antennomeres 3 = 6> 2 = 4 = 5> 7> 1 ( Figs 4 View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5 , 6B, C View FIGURE 6 ); only antennomere 6 with a distinct, compact, roundish, distodorsal group of bacilliform sensilla ( Figs 4D View FIGURE 4 , 6B View FIGURE 6 ). Genae roundly squarish, gnathochilarium without peculiarities ( Fig. 6B View FIGURE 6 ).

In width, collum <head ≤ ring 2 = 3 <4 <5=16(17) (male, female), thereafter body gradually tapering towards telson ( Figs 4A–C View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5 ). Paraterga very strongly developed in both sexes, set high ( Figs 6C–F View FIGURE 6 , 7A–C View FIGURE 7 ), especially so in adults compared to subadults and younger instars, only on collum and ring 19 faintly convex with subhorizontal sides, on rings 2–18 clearly upturned and elevated above dorsum; large, broadly and regularly rounded shoulders on paraterga anteriorly, sides only slightly and regularly rounded, whereas caudal corners invariably acute, beakshaped to spiniform, prominent, increasingly produced past rear tergal margin, especially well so on ring 19 ( Figs 6C–F View FIGURE 6 , 7A, B View FIGURE 7 ). Lateral margin of postcollum paraterga with two (poreless rings) or three (pore-bearing rings) small setigerous indentations and a seta at caudal corner. Pore formula normal, ozopores inconspicuous, round, located laterally in front of caudalmost incision ( Fig. 6E, F View FIGURE 6 ). Collum and following metaterga with regular, medium-sized to short, very delicately helicoid, mostly acute and bacilliform setae arranged in three transverse rows typical of most polydesmoids; polygonal bosses missing ( Figs 6C–F View FIGURE 6 ). Stricture between pro- and metazonae wide, shallow and smooth. Limbus very thin, very faintly microdenticulate, nearly smooth. Pleurosternal carinae small bulges traceable only on rings 2–4 ( Fig. 6C View FIGURE 6 ). Epiproct short, conical, directed caudoventrally, tip subtruncate; pre-apical papillae small ( Figs 6F View FIGURE 6 , 7B View FIGURE 7 ). Hypoproct trapeziform, setiferous papillae at caudal corners evident, rather well separated, borne on small knobs; sides slightly concave ( Fig. 7B View FIGURE 7 ).

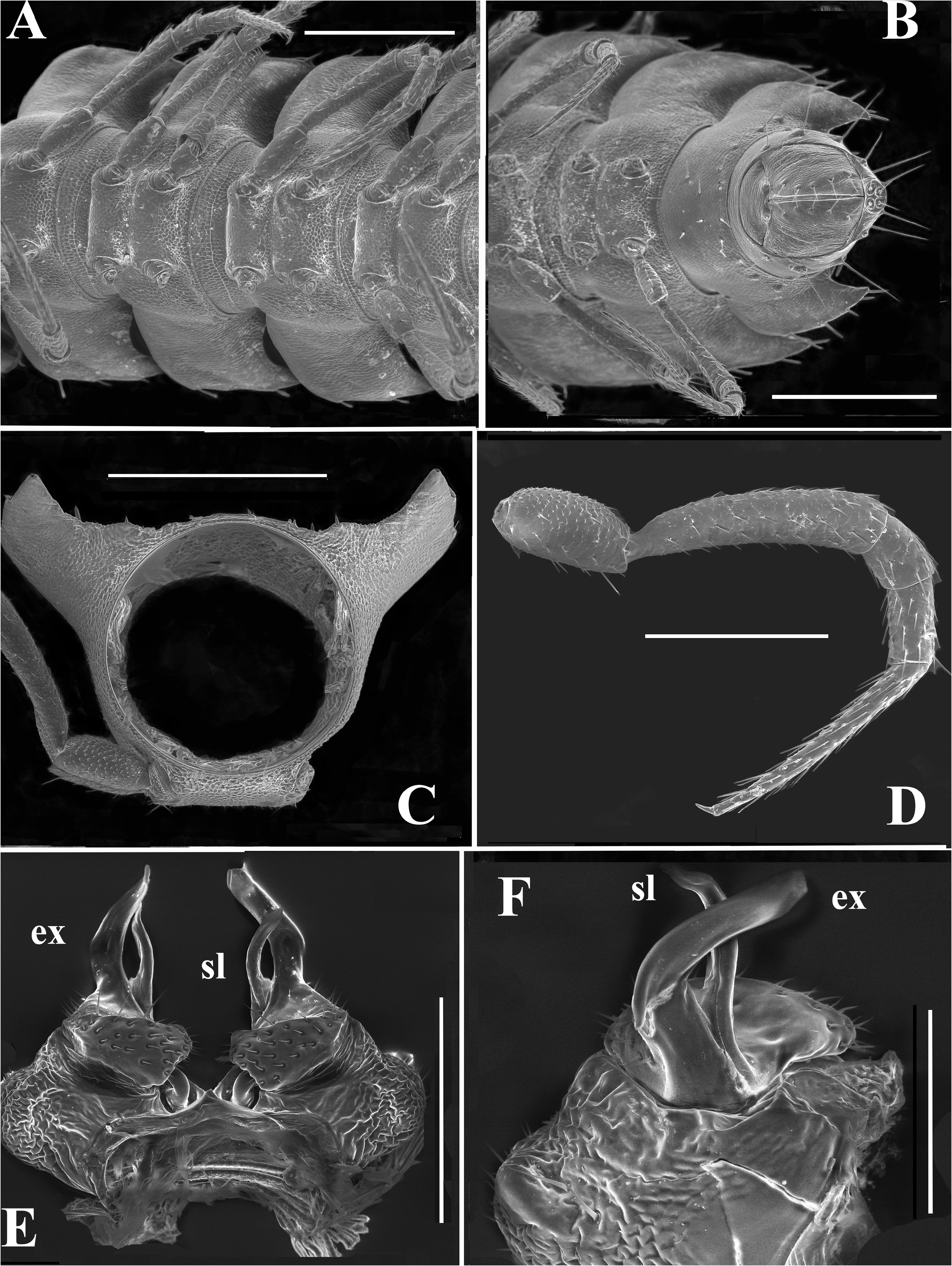

Sterna broad, without modifications, poorly setose ( Fig. 7A, B View FIGURE 7 ). Epigynal ridge very low. Legs very long and slender ( Figs 4A–C View FIGURE 4 , 5 View FIGURE 5 , 7D View FIGURE 7 , 8A View FIGURE 8 ), ca 1.3–1.4 times as long as midbody height (male, female); male legs with clearly micropapillate prefemora, finer and sparser micropapillae being traceable on femora as well; tarsi especially long and slender, claw very short and simple; sphaerotrichomes absent ( Figs 7D View FIGURE 7 , 8A View FIGURE 8 ).

Gonopod aperture subcordiform, about as broad as male prozona 7. Gonopods ( Figs 7E, F View FIGURE 7 , 8B, C View FIGURE 8 ) simple, coxites only moderately enlarged, subglobose, micropapillate and microsetose laterally, cannulae typical hollow tubes; telopodites only slightly sunken into a shallow gonocoel, apical parts being well exposed, and held parallel to each other; each telopodite deeply biramous, directed ventrad; prefemoral (= densely setose) parts short and held subtransversely to main body axis, but acropodites suberect and lying parallel to each other; telopodite consisting of two slender and simple branches: a shorter solenomere (sl) lying mesal to a longer, slightly coiled and similarly simple exomere (ex).

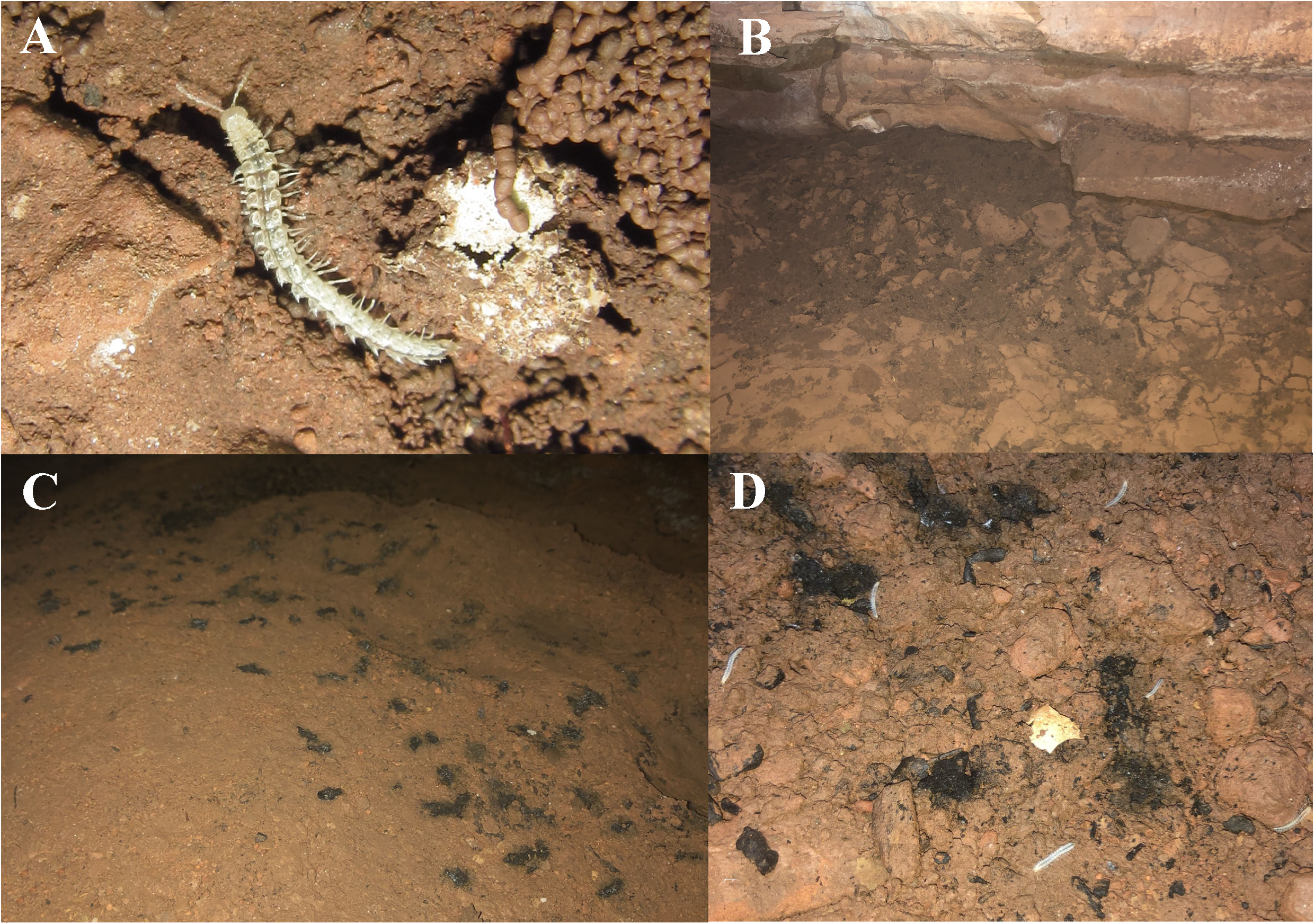

Remarks. This species is an unquestioned troglobiont not only because it shows a full set of troglomorphic traits characteristic of a Polydesmida (an enlarged and unpigmented body, strongly broadened paraterga, and elongate extremities), but also because of our observations of its biology and behaviour monitored both inside the cave habitat and in the lab. The animals are relatively fast to move, this contrasting with the behaviour observed for most other cave polydesmidans. When subjected to light (flash lamps, approximately 500 lux of intensity), they quickly run away, walking backwards or burrowing in the clay substrate. In the travertine pools, the millipedes hide in crevices on the rocky substrate. Both behaviours are evidence of a strong photophobic reaction, as observed in epigean and hypogean diplopods, and this character state being considered plesiomorphic (e.g., Gallo & Bichuette 2017). Individuals were also observed moving the antennae and quickly probing the substrate to perceive the environment and escape from the obstacles.

The population observed in the cave was revealed to be large, most animals being found exposed in very humid microhabitats: clay with diplopod feces, cracks ( Fig. 9A, B View FIGURE 9 ), organic matter, hematophagous bat guano ( Fig. 9C View FIGURE 9 ), and dry travertine pools ( Fig. 9D View FIGURE 9 ). The population density reaches 4–5 individuals per sq. m, the counts through visual censuses totaling ca 90 individuals along a 200-m long cave conduit. During the rainy season, these microhabitats are completely submerged, this keeping the humidity high even in the dry season. The animals were observed staying rather close to each other ( Fig. 9D View FIGURE 9 ), but without obvious gregarious habits. Juveniles and adults were observed abundant all over the aphotic zone of the cave ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ), indicating that the population is well established there. The type series likewise contained not only adults, but also a few juvenile instars of various ages (see above), again pointing to a stable subterranean population. Since the Gruna da Serra Verde cave can readily be postulated as possibly representing perhaps the only refuge for this species, apparently strongly hygrophilic, highly sensitive to the semi-arid climate of the region, and clearly threatened, that it definitely requires protection.

| ZMUM |

Zoological Museum, University of Amoy |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |