Monachus schawinslandi, Fleming, 1822

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6607185 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6607193 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/464F694F-FFA8-A855-FFBF-D7E090AEFD94 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Monachus schawinslandi |

| status |

|

Hawaiian Monk Seal

French: Phoque d'Hawai / German: Hawaii-Monchsrobe / Spanish: Foca monje de Hawai

Other common names: Common Hawaiian Monk Seal

Taxonomy. Monachus schawinslandi Matschie, 1905 ,

“Laysan ist eine kleine Koralleninsel, nordwestlich der Sandwich-Inseln” (= USA, laysan I, 25° 50’ N, 171° 50° W).

This species is monotypic.

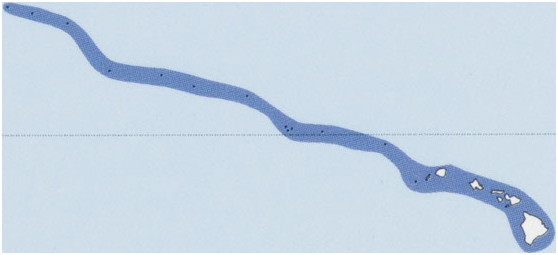

Distribution. Mainly in NW Hawaiian Is (Kure Atoll, Midway Atoll, Pearl and Hermes Reef, Lisianski I, Laysan I, and French Frigate Shoals) but increasingly seen at the main Hawaiian Is. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 183-240 cm; weight 136-272 kg. Newborns are 100 cm in length and weigh 16-18 kg. Female Hawaiian Monk Seals are slighter larger than males. Neonates have woolly black pelage that is molted near weaning at c.6 weeks old. Pelage ofjuveniles is silver gray dorsally and laterally and tan ventrally just after molting; it fades to brown dorsally and laterally and yellow ventrally with age. Pelage of adult Hawaiian Monk Seals is darker brown dorsally and tan or yellow ventrally. When molting, upper layer of epidermis is shed with hair in large patches.

Habitat. Breed at small atolls and islands in the north-western Hawaiian Islands, and several have been seen on the main Hawaiian Islands. Hawaiian Monk Seals forage within 50-100 km of breeding sites.

Food and Feeding. Hawaiian Monk Seals are generalist predators and have very diverse diets of fish, cephalopods, and crustaceans. Foraging by Hawaiian Monk Seals evidently occurs on the seafloor, or perhaps in the water column, within atoll lagoons and near seamounts along the Hawaiian Island Archipelago. In a 1991-1994 study of 940 feces and regurgitated samples from Hawaiian Monk Seals in the north-western Hawaiian Islands, diets comprised 78:6% teleosts from 31 families, 30 of which were reef-associated species offish; 15:7% cephalopods, including 21 squid species and seven octopus species; and 5-7% crustaceans. The most common families in the diet were Labridae , Holocentridae , Balistidae , Scaridae ; marine eels were also eaten. Diets in this study varied among years and among juvenile, subadult, and adults of both sexes of Hawaiian Monk Seals.

Breeding. Female Hawaiian Monk Seals give birth to single offspring mostly in March-June, although some are born as early as December and as late as mid-August. Females nurse their offspring for c.6 weeks and then go into estrus. Adult male Hawaiian Monk Seals patrol along beaches and threaten other male competitors vocally and sometimes physically; males attempt to mate with estrous females when they enter the water to forage.

Activity patterns. Most Hawaiian Monk Seals make regular foraging trips of several days to a couple of weeks from breeding and haul-out sites on the main and northwestern Hawaiian Islands to along-shore and offshore foraging areas. When on shore, they are largely immobile to conserve energy and avoid overheating.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Hawaiian Monk Seals are considered non-migratory and tend to remain near the atoll where they were born, but they do travel substantially to forage within ¢.100 km of the north-western Hawaiian Island Archipelago and around some of the main Hawaiian Islands. Hawaiian Monk Seals haul-out regularly between foraging trips of several days to several weeks most of the year, but they are not particularly social or gregarious. They are generally solitary when on shore, except for females and their nursing offspring and when foraging at sea.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The Hawaiian Monk Seal has been listed as an endangered species under the US Endangered Species Act since 1976. Hawaiian Monk Seals were likely never very abundant, but they were hunted extensively in the north-western Hawaiian Islands soon after Europeans discovered them in the early 1800s and were quickly reduced to near extinction by 1824. In 1958, direct counts of Hawaiian Monk seals on beaches in the north-western Hawaiian Island Archipelago totaled 916 individuals; similar counts in 1983 totaled 1488 individuals, but by 2007, the total count had fallen to 935 individuals, a decline of 37% in 24 years. Projections of population change since 1999 suggested a decline of 41% /year. The total population of Hawaiian Monk Seals is now estimated at ¢.1000 individuals, with ¢.591 sexually mature individuals, but it continues to be declining because of poor survival of neonates and juveniles and aging of the adult female population. The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the agency with delegated authority to conserve and manage marine species, has been unable to halt or slow the decline of the Hawaiian Monk Seal and has also been unable to identify and resolve the causes for it. Conservation threats include food limitation caused by changes in oceanographic conditions and competition with fisheries and other marine predators; entanglement in discarded fishing nets and other marine debris; predation by sharks, particularly on young Hawaiian Monk Seals; and limited availability of terrestrial habitat for giving birth and resting. In the entire north-western Hawaiian Island Archipelago, only c.13-5 km? ofterrestrial habitat is available overall, and only a small part of that is suitable for the Hawaiian Monk Seal. Fortunately, nearly all of the land and water in the north-western Hawaiian Island Archipelago is protected, with no orstrictly controlled human access,in several protected areas included in the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument.

Bibliography. Gerrodette & Gilmartin (1990), Goodman-Lowe (1998), Kenyon (1972), Lowry & Aguilar (2008), Rice (1960), Stewart, B.S. et al. (2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.