Labrorostratus caribensis, Hernández-Alcántara, Pablo, Cruz-Pérez, Ismael Narciso & Solís-Weiss, Vivianne, 2015

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4048.1.8 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:B8764598-61D9-4F16-980C-887B7BD344B6 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5627925 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0385CE33-FFC8-FFCD-FF25-7D9BFEA8F955 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Labrorostratus caribensis |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Labrorostratus caribensis View in CoL new species

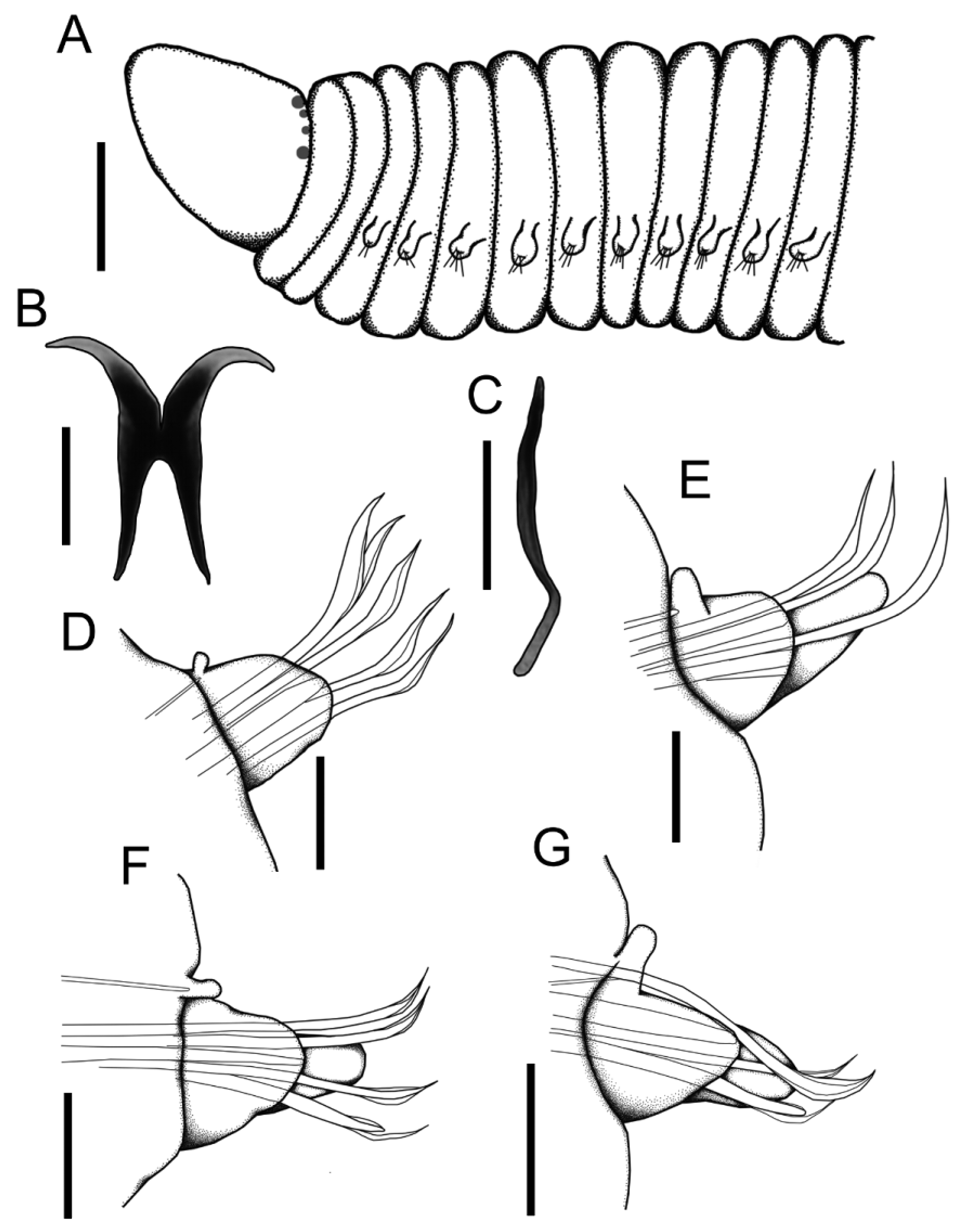

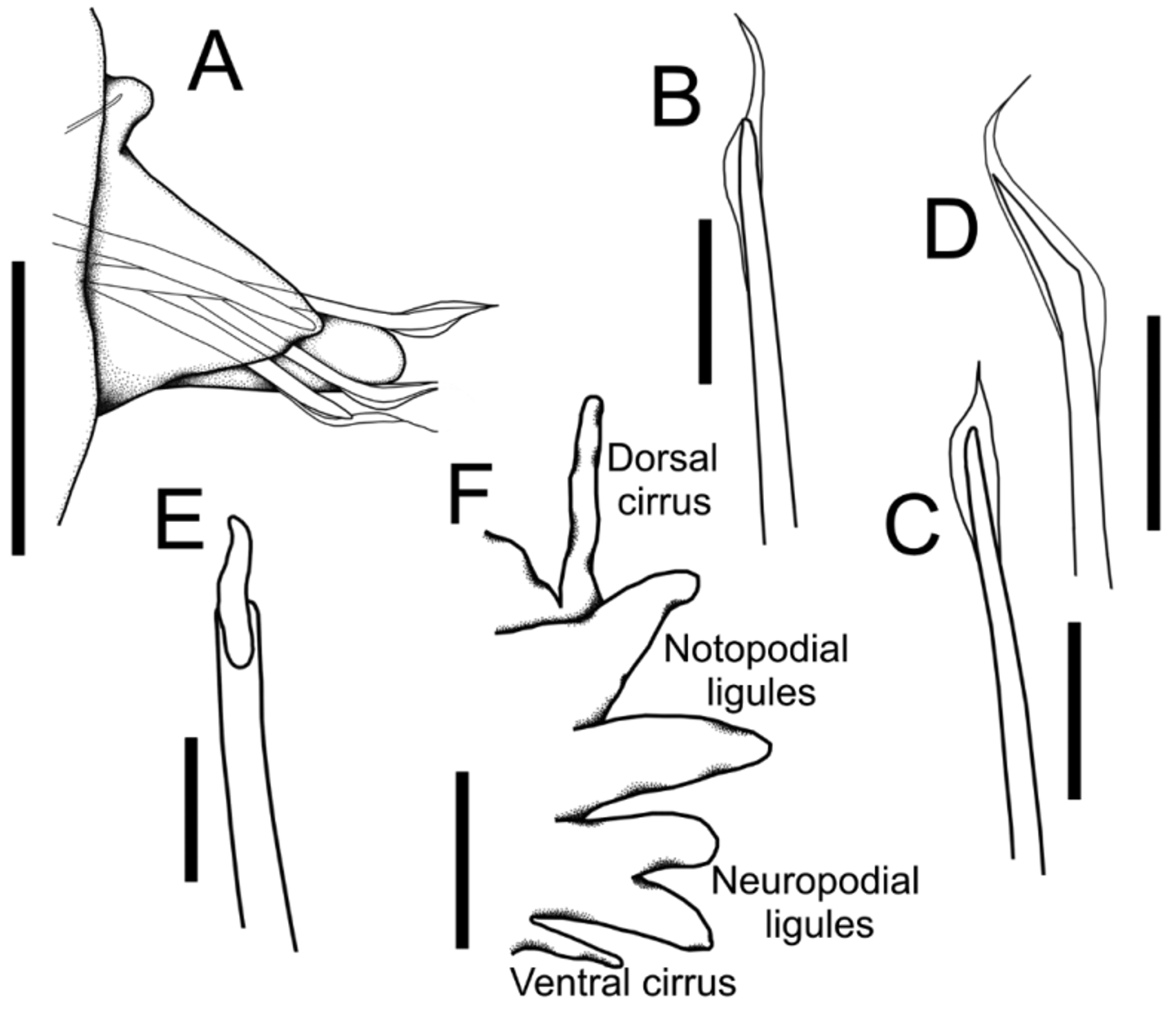

Figures 1 View FIGURE 1 A–G, 2A–F

Type material. Holotype (CNP– ICML, POH–56–002), one specimen living in the body cavity of Nereis sp. ( Nereididae ), Chinchorro Bank, Mexican Caribbean, Station 5 (18° 35' 01.1''N; 87° 22' 28.3''W); 13 April 2008; 4.5 m depth; coll. V. Solís-Weiss.

Description. Complete specimen with 153 segments, 10 mm long and 0.5 mm wide, not including chaetae ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A). Body slender, cylindrical. Color of preserved specimen light brown. Prostomium conical, larger than wide, flattened dorsoventrally, without appendages. Four rounded black eyes near posterior edge of prostomium, arranged classically in a transverse row, inner pair smaller ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 A). Peristomium with two apodous and achaetous rings, subequal in length, wider than base of prostomium. Mandibles dark-brown, well developed, with no teeth, each strong and wing-shaped; both narrowly joined along median line ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 B). Maxillary apparatus with only maxillary carriers fused, elongated, rod-like, dark-brown, twice as long as mandibles; fangs or distinct maxillary plates absent ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 C). Parapodia well developed throughout, with prechaetal rudimentary lobes, and bluntly conical postchaetal lobes ( Figs 1 View FIGURE 1 D–G, 2A). First parapodia small, progressively increasing in size, then gradually reducing from mid-body to posterior end. Aciculae yellow, large, one per parapodium, some slightly projecting outside postchaetal lobe. Chaetae simple, limbate, geniculate, with smooth asymmetric wings, tapering to fine tips ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D); up to four simple chaetae per parapodium, superior chaetae longer than others. On posterior third of body, the superior simple chaetae are geniculate, with short, smooth and symmetrical wings ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 C). One modified ventral chaeta per parapodium from chaetiger 18, thicker than other chaetae, with a flat extension on distal end, and a smooth shaft ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 B). Pygidium rounded, anal cirri absent.

Host. The absence of the host anterior region prevented us to identify it to species ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 E, F). However, the homo- and heterogomph spinigers, the heterogomph falcigers in the neuropodia, and the characteristic notopodial homogomph falcigers ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 E), allowed us to recognize it as a member of the genus Nereis . This is the first known relationship between an oenonid and a nereidid from the Grand Caribbean, and the second record worldwide, since only the oenonid Labrorostratus prolificus had been reported from the northern coast of Sao Paulo, Brazil, as a parasite of the nereidid Perinereis cultrifera ( Grube, 1840) .

Remarks. Up to now, seven species of Labrorostratus have been described, including the new taxon from the Mexican Caribbean. Except L. jonicus from Italy, L. luteus from Bahamas, and L. parasiticus from the Mediterranean Sea, all other species are exclusive parasites in polychaetes. L. jonicus was originally described from a single anterior fragment collected as free-living among algae and other polychaetes, including syllids, but Tenerelli (1961) emphasized that it may have come out from one of the polychaetes. L. luteus and L. parasiticus were originally described as parasites in several species of Syllidae ( Table 1), but later on, L. luteus was also collected as free-living in coarse and fine sand sediments ( Uebelacker 1984), and L. parasiticus was also reported as free-living among calcareous algae ( Pettibone 1957).

The jaw apparatus reduced to the maxillary carriers of L. caribensis n. sp. clearly separates it from other members of the genus. It is only close to L. jonicus and L. luteus due to the modified ventral chaetae ( Table 1), which are exclusively present in these three parasitic oenonids. These chaetae, however, are common in free-living genera such as Arabella , but Colbath (1989) showed that the modified ventral chaetae in Arabella have no hood. Instead of this apparent “hooded” condition, the chaetae have a relatively flat extension of the chaetal shaft, as it was observed in the new species.

The degree of asymmetry of the chaetae can vary within an individual, which is why this is not a robust feature to separate species ( Colbath 1989). However, the two shapes of simple chaetae observed in L. caribensis n. sp.: limbate with asymmetric wings in anterior and medium body, and limbate with short, symmetrical wings in posterior body, helped to distinguish the new species from all other known parasitic oenonids.

Modifications of the maxillary apparatus of the endoparasitic polychaetes could be associated to a progressive adaptation to this mode of life: the mandibles are well developed in most species, but the jaws tend to be small sized ( Clark 1956; Martin & Britayev 1998). The scarcity of specimens collected worldwide makes it difficult to explore the life history of endoparasites and to know and evaluate their morphological changes through their growth stages and life history. The reduction and specialization of their mouth parts could be the reason why several genera of parasitic oenonids have been erected and comprise only one or two species. This is the case of Drilognathus and Pholaidiphila (monospecific), and Oligognathus and Haematocleptes (two species) ( Table 1). In L. caribensis n. sp., the jaw plates are lacking and the shape of their maxillary carriers is similar to those observed in Drilognathus capensis Day, 1960 , described from a single specimen, possibly not even adult ( Martin & Britayev 1998). However, the size of the Caribbean specimen (10 mm for 153 segments) suggests that the absence of jaw plates is not associated with a juvenile stage. Although the phases of maxillary development in endoparasitic polychaetes are poorly known, Amaral (1977) and Steiner & Amaral (2009) observed that individuals of L. prolificus with 41–65 segments and 3.1–11 mm long had the jaw apparatus fully developed and the two pairs of eyes well formed. Likewise, specimens of L. parasiticus with 57 segments and 8 mm long ( Saint Joseph 1888), of Labrorostratus sp. with 39 segments and 2.5 mm long ( San Martín & Sardá 1986), and individuals of L. luteus with 80 segments and 7.5 mm long ( Uebelacker 1978) also had the maxillae and the four eyes completely formed.

Etymology. The specific epithet, caribensis , refers to the marine region where the species was found, the Mexican Caribbean, called “Caribe” in Spanish.

Habitat. Inside the body cavity of Nereis sp., from dead coral rocks, 4.5 m depth, temperature of 26.41°C and 35.76 0/0 0 of salinity.

Type locality. Chinchorro Bank, Mexican Caribbean (18° 35' 01.1''N; 87° 22' 28.3''W).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |