Ibericancer sanchoi, Artal, Pedro, Guinot, Danièle, Bakel, Barry Van & Castillo, Juan, 2008

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.184516 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6233908 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03E5D65B-EF32-3F78-079C-FE65FDBAD37F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Ibericancer sanchoi |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Ibericancer sanchoi View in CoL sp. nov.

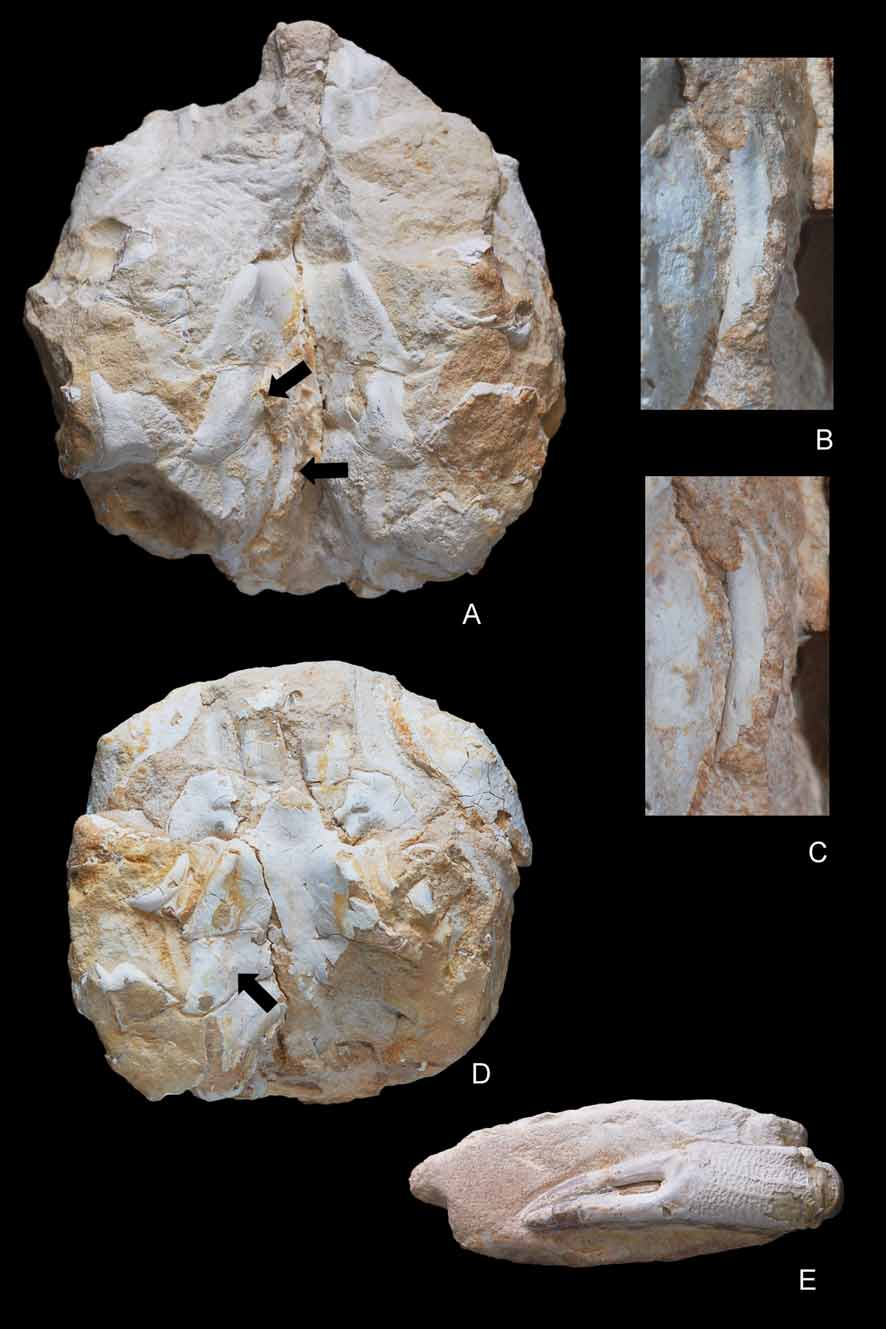

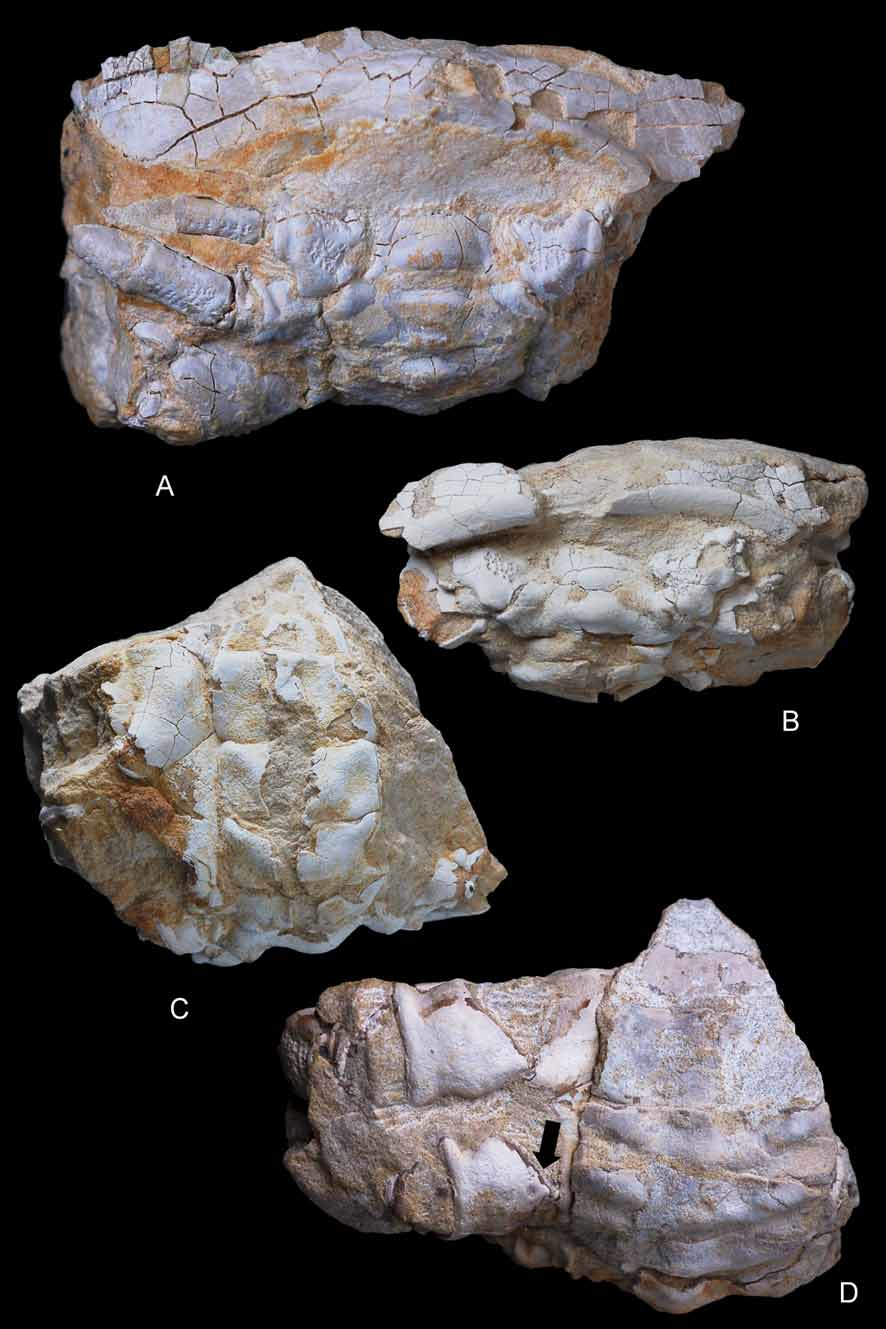

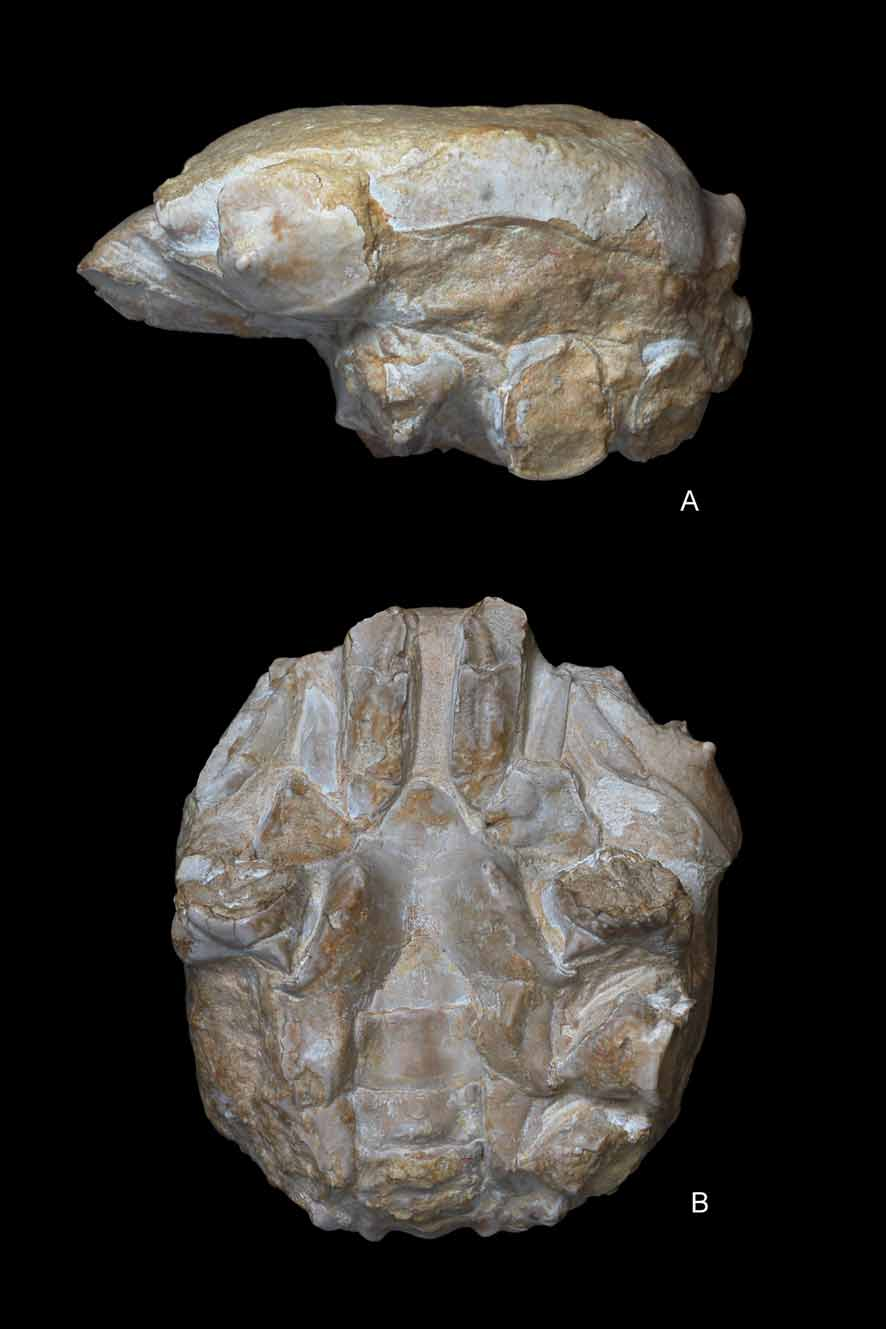

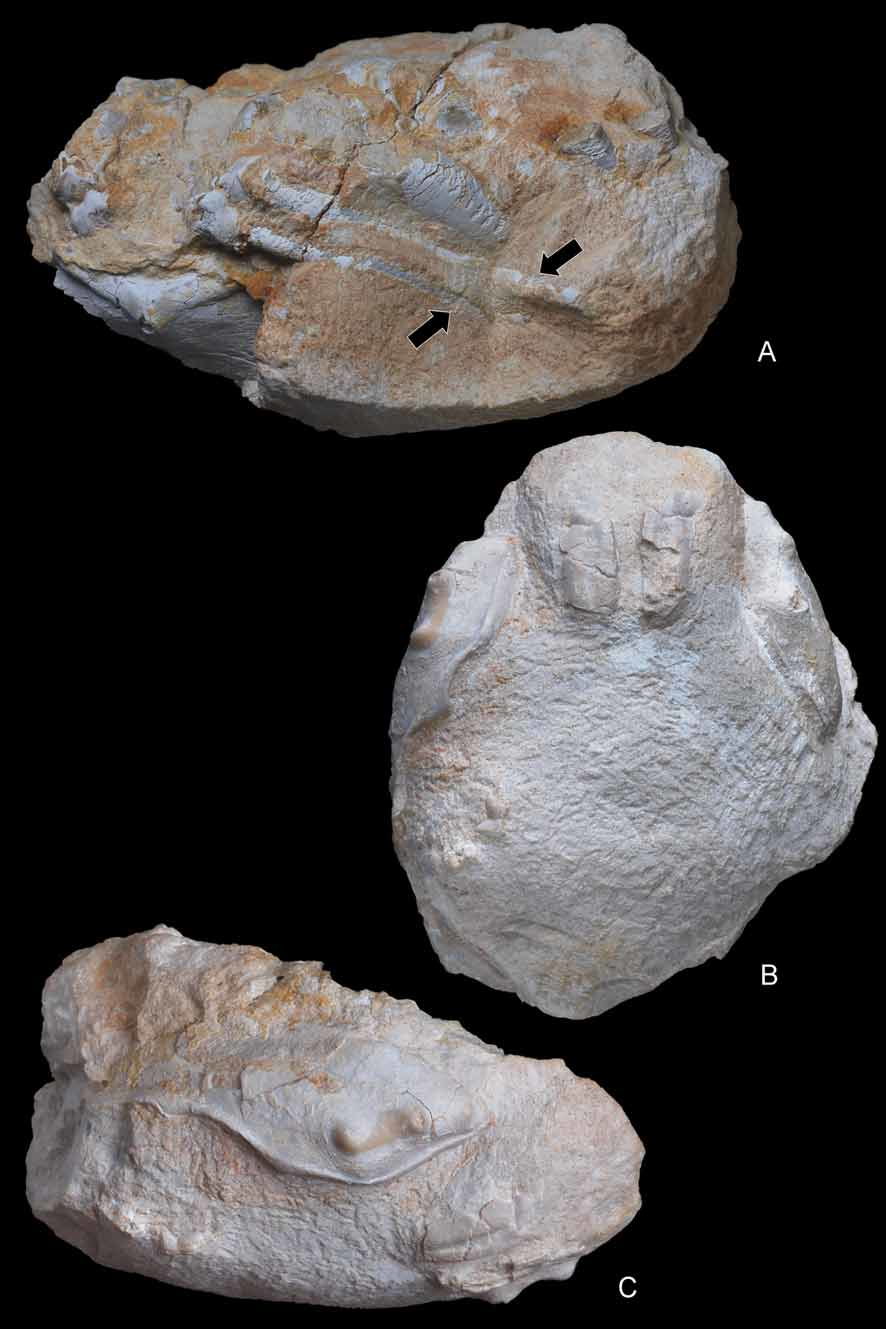

( Figs. 4–10 View FIGURE 4 A – E View FIGURE 5 A – D View FIGURE 6 A, B View FIGURE 7 A – C View FIGURE 8 A – D View FIGURE 9 A – C View FIGURE 10 A – D )

Diagnosis. Same as in the family.

Etymology. In honour of the late Mr. Fausto Sancho (Gandía, Spain), who discovered the new species.

Type material. Holotype, male, ( MGSB 68572); paratypes, male and female specimens ( MGSB 68573a–h and MGSB 68574a–f). Maximum size (in millimeters): W 49, L 59. Minimum size: W 37, L 36.

Type locality: Pla de la Basa, Valencia, Spain. Upper Cretaceous, late Campanian.

Other material examined. Pla de la Basa, Valencia, Spain ( MGSB 68575a–h).

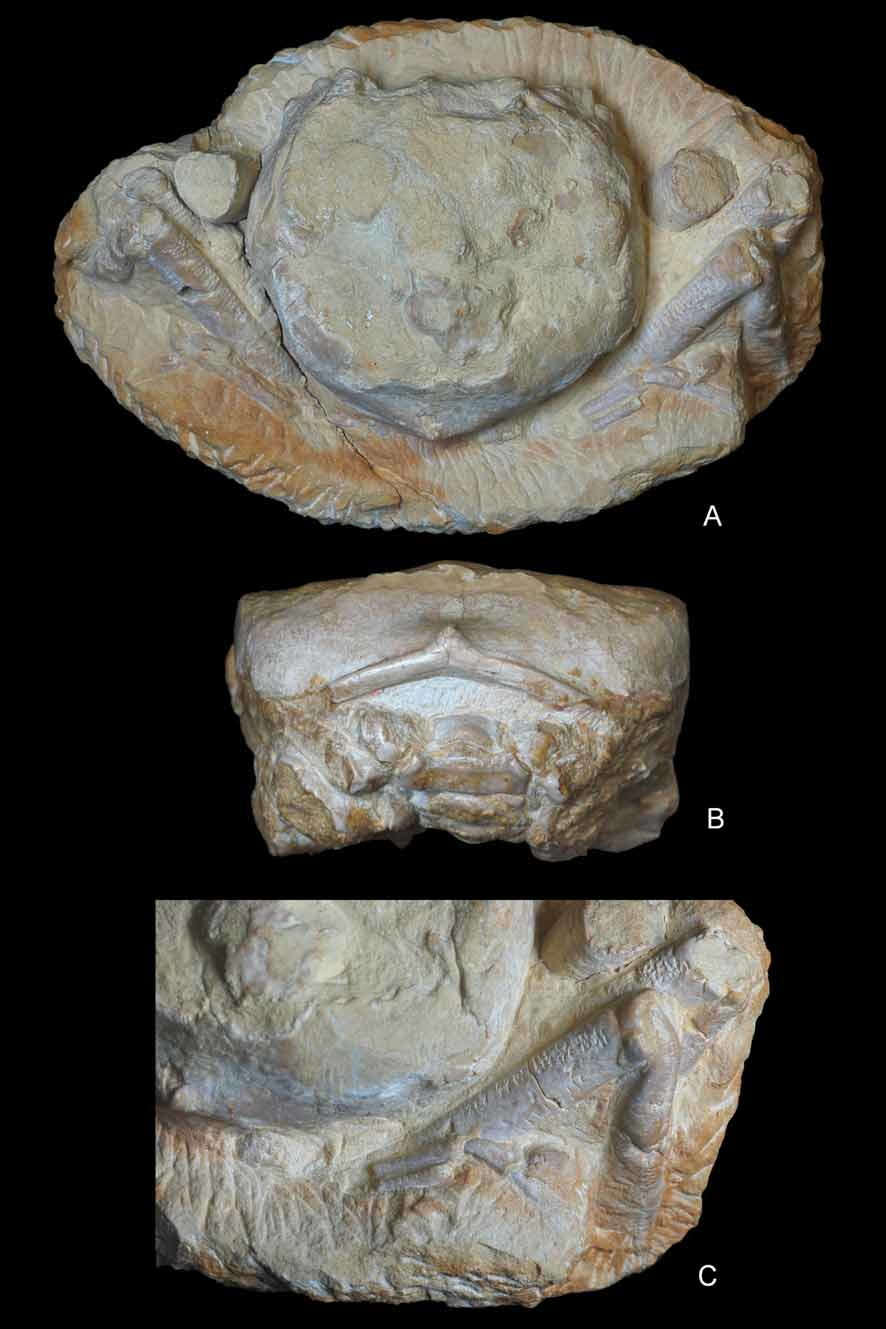

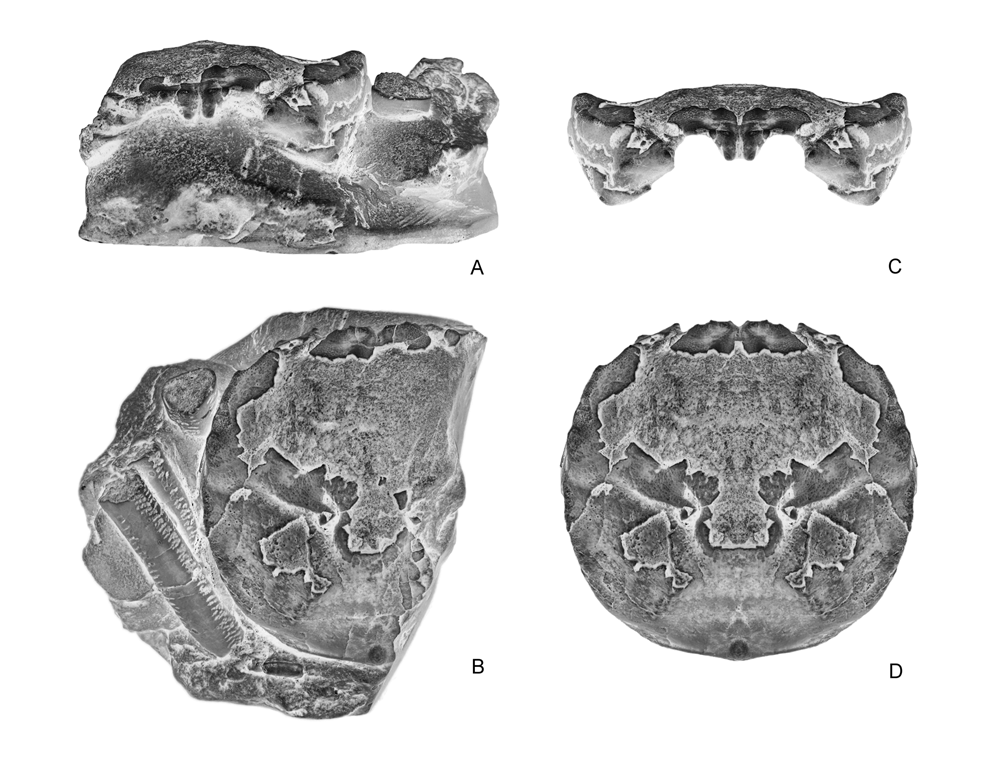

Description. Carapace of large size, nearly as broad as long; suboval shape with smoothly arched margins posterior to pronounced branchiocardiac furrow; dorsal surface strongly convex longitudinally, nearly flat transversely. Dorsal surface finely and densely granular. Fronto-orbital margin about 53% of maximum carapace width, rather advanced. Front occupying 46% of anterior margin, delimited by two protuberant nodes at internal orbital sides, slightly concave in dorsal view, clearly notched axially, bearing 2 blunt nodes at base of rostrum; rostrum narrow, strongly deflected downwards, about 90 degrees, deeply grooved medially, terminating in a bifid end with rounded lobes. Proepistome as a very thin plate, epistome well defined. Orbits small, directed forwards, bounded by frontal lobe and outer orbital spine; supraorbital margin strongly modified by a salient, triangular, robust spine, deep fissure between medial, extraorbital spines, short infraorbital margin with small terminal spine. Ocular peduncles probably well sheltered inside orbits.

Lateral margins arched; anterolateral margin slightly shorter than posterior, ornamented by a thin spine close to outer-orbital, followed by a concavity and a short, salient ridge; anterolateral margin joining the posterolateral posteriorly to a rather large and swollen epibranchial node. Posterolateral margin gently arched, continuous, not interrupted by nodes or notches. Posterior margin concave per se, gently convex in dorsal view, somewhat broader than fronto-orbital width; notably rimmed, affected axially by a strong conical protuberance. In posterior view, posterior border robust, V-shaped, with apex directed upwards.

Dorsal regions relatively inflated, not strongly protuberant or grooved except for branchiocardiac groove, some depressions, rare swellings. Gastric regions broad, swollen, undivided, occupying major surface of anterior half of carapace. Hepatic region not well defined, marked by a slight depression. Epibranchial region long, transversely inflated, curving abruptly at level of cardiac region, forming small terminal protuberance. Branchiocardiac groove smooth, moderately deep, more marked axially. Cardiac region large, being individualized by a slightly swollen, nearly circular lobe. Postbranchial regions obliquely ridged, diverging backwards, bounded by broad, depressed intestinal area.

Pterygostomial region inflated, ornamented with a row of three large tubercles. Pleural suture located on carapace sides. Third maxillipeds broad, not divergent, separated by a straight gap; noticeably long, exceeding front; ischium, merus in same plane; endopod much longer than wide, with deep longitudinal groove on ischium; coxa very broad, trapezoidal, with lower margin bearing two small protuberances at level of sternal articulation; exopod thin, long, sharp at termination.

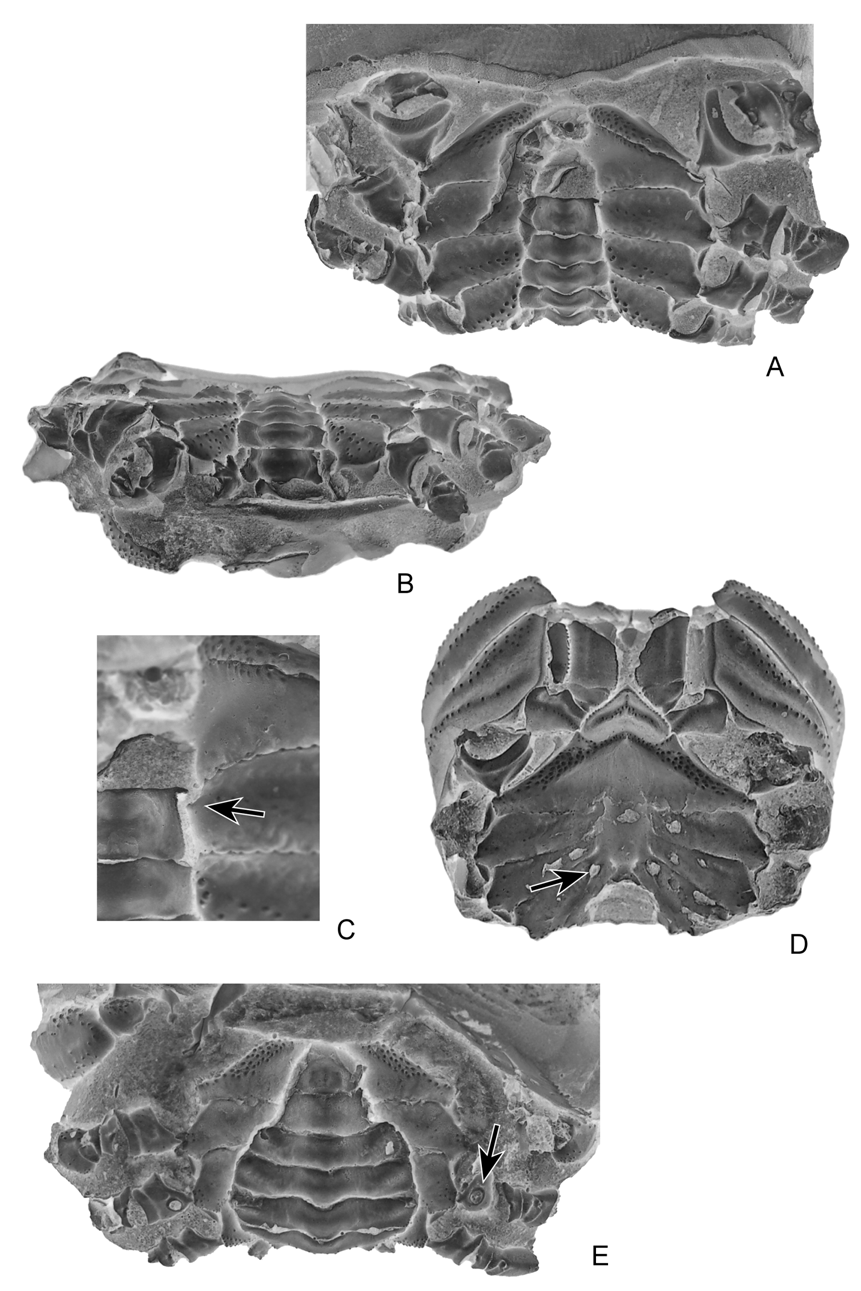

Thoracic sternum relatively wide, stout, strongly elevated laterally; a rather large portion of sternum visible between P1, P2 coxae and male abdomen. Sternites 1–4 fused, forming a broad triangle visible nearly entirely in ventral view; anterior portion (1–3) narrow, pointed forwards, inserted between bases of mxp3; episternite 3 very small, only a reduced salient portion where coxa of mxp3 is articulated; sternite 4 well developed, with lateral margins strongly elevated, forming an acute ridge, episternite 4 small, extended laterally, slightly curved; sternite 5 as wide as sternite 4, subrectangular, nearly horizontal; sternite 6 narrower, slightly oblique; sternite 7 very reduced, oblique, mostly covered by third pleomere; sternite 8 reduced, oblique, completely covered by second pleomere. Thoracic sutures 4/5 to 7/8 not reaching axial area, preceding sutures 1/2, 2/3 absent. Presence of a small tubercle on sternite 5, at level of pleomere 6, which is supposed to be a press button for the abdominal holding mechanism. Female gonopore on P3 coxae very small, nearly elliptical, gently rimmed; male gonopore on P5 coxae, somewhat larger, fairly elliptical, not rimmed; spermatheca at end of sternal suture 7/8, aperture large, ovate, somewhat oblique.

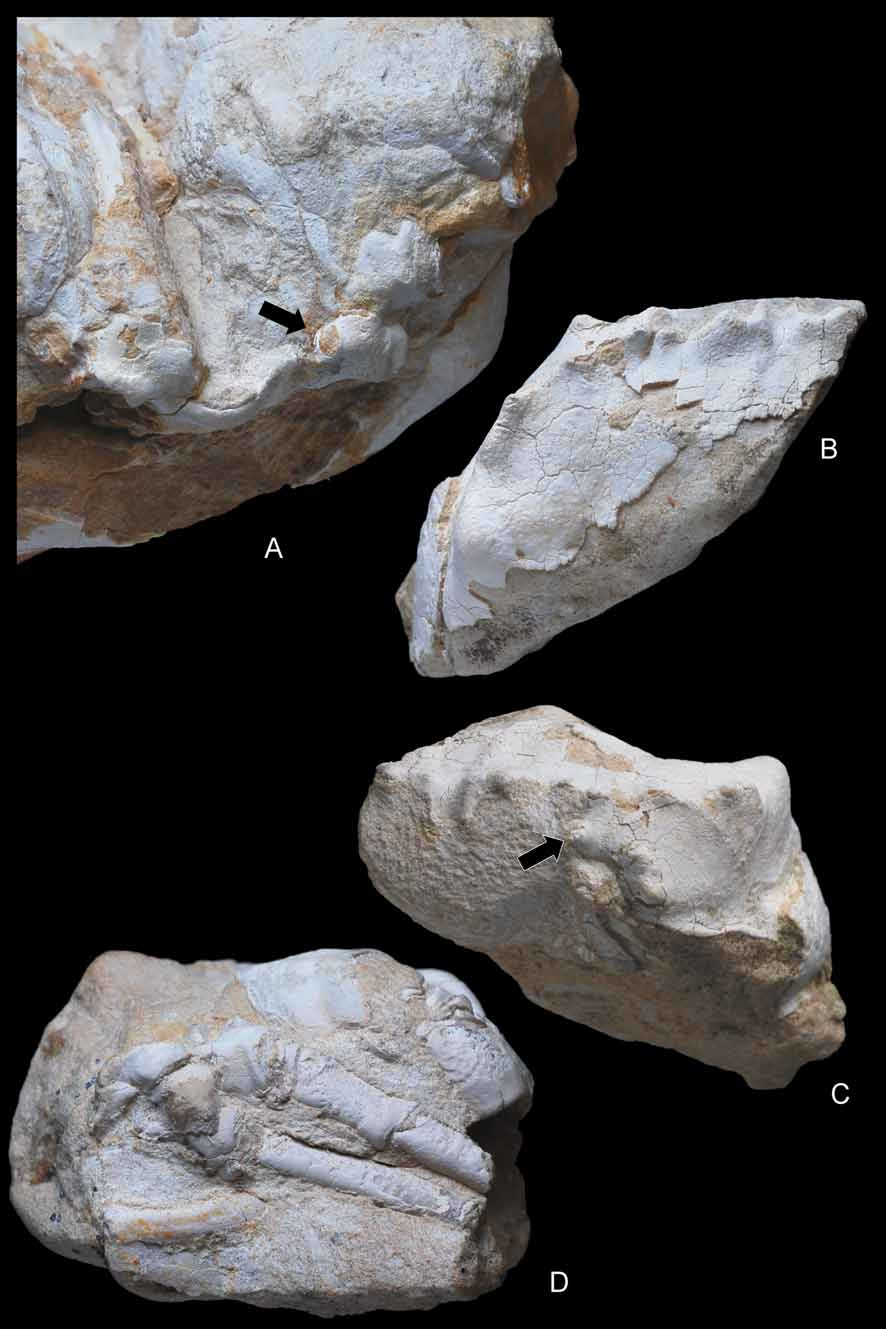

Abdomen rather wide in males, not much widened in females; nearly rectangular over its entire length in males, triangular in females; strongly sculptured, presenting two longitudinal grooves and transverse crests on its first pleomeres. All pleomeres free, subrectangular, with salient small lobes at upper margin of each segment. A1 very narrow, convex in male; a2 slightly wider, notably sculptured, medially keeled, with elevated lateral extensions covering male gonopore on P5 coxa; a1 to a6 with straight margins, increasing in length from a3 to a6; telson triangular. Female abdomen roughly similar in shape, only slightly broader; pleomeres a1–a6 and telson with more clearly arched lateral margins conferring a more suboval-triangular outline. G1 thick, long, very stout, probably rolled (see Fig. 4B, C View FIGURE 4 A – E ).

Chelipeds of equal size, finely granulated; merus long, robust, subtriangular in section; propodus slender, longer than wide, subelliptical in section; fingers very long, thin. P2, P3 very long, robust, coxa subtriangular, stout; basis narrow; ischium robust, curved; merus very long, circular in section, curved at first proximal portion. P4, P5 subdorsal, conspicuously reduced, subequal, rather long, with smaller coxae. P4 coxa subtriangular, basis narrow, ischium straight, long, merus very long. P5 coxa robust despite its reduced size; rather complex in shape, with acute, thin ridge at upper margin; merus long; dactylus small, probably curved.

Remarks on dakoticancroid spermathecae. Bishop et al. (1998: 239) stated in the diagnosis of the Dakoticancridae that the female sternum lacked “longitudinal grooves”. The term “longitudinal grooves” was used by these authors as well as by many neontologists (e.g., Gordon 1950) to designate the condition of these sutures found in the Dromiidae . The term “groove” is not appropriate to describe the suture 7/8, which is short ( Dynomenidae , Homolodromiidae , Sphaerodromiinae ) or developed as an elongated and salient tube in the Dromiinae (see Guinot & Tavares 2003; Guinot & Quenette 2005). We propose to use ‘suture’ as the appropriate term.

In Ibericancer sanchoi View in CoL n. gen., n. sp. ( Fig. 4D View FIGURE 4 A – E ), as well as in Dakoticancer overana View in CoL (see Guinot 1993: fig. 7; Guinot & Tavares 2001: fig. 7H), and Tetracarcinus subquadratus View in CoL (see Roberts 1962: pl. 87, fig. 3), the thoracic sternal suture 7/8 is rather short and ends in a large orifice. Referring the Dakoticancridae View in CoL as not having “longitudinal grooves” might give the wrong impression that sutures 7/8 are not present and thus do not play a reproductive role. Such a role is performed by dakoticancroid sutures 7/8 since their distal portions bear a large orifice as in all podotreme crabs ( Guinot & Tavares 2001: 522, fig.10). Only the raninoid spermathecae present a special pattern (see Hartnoll 1979). In the Dakoticancroidea, although dependent of the same phragma 7/8, the spermatheca with its large aperture at the extremity of suture 7/8 does not appear similar to that of the Dromiacea and Homoloidea. It can only be inferred that its internal organisation is different.

The diagnosis of the family Dakoticancridae View in CoL by Bishop et al. (1998) is proposed herein to be modified as: “sternum of females with oblique sutures 7/8 and presence of large rounded orifices at their distal portions, which are homologous to the spermathecal apertures” (see also Guinot & Quenette 2005: 317).

The thoracic sternum is wider in the Dakoticancroidea than in the Dromiacea. Sutures 4/5, 5/6 and 6/7 are developed and, instead of being short and confined laterally as in the Dromiacea, the sutures reach the sternoabdominal cavity ( Dakoticancridae ) or the median depression ( Ibericancridae n. fam.) (only a sternoabdominal depression in the Dromiacea; see Guinot & Bouchard 1998). Sutures 7/8 are much shorter in the Dakoticancroidea than in the Dromiinae , and the distal aperture is large and rounded instead of a usually small aperture in the Dromiinae .

No affinities are suggested with the thoracic sternum and sutures 7/8 of the Homoloidea, in which, additionally, suture 6/7 is complete. There is a resemblance with the Cyclodorippoidea Ortmann, 1892, which have a broad sternum, with (typically) slit-like distal spermathecal apertures ( Guinot & Tavares 2001: fig. 10F, I, J; Guinot & Quenette 2005: fig. 23).

The Etyidae Guinot & Tavares, 2001, is a fossil podotreme family in which the spermathecae are known. Two oblique and large slits at the extremities of the short sutures 7/8 have been described for Etyus martini Mantell, 1844 , from the European mid-Cretaceous ( Wright & Collins 1972: 102, pl. 21, fig. 6d, e; Guinot & Tavares 2001: figs 2, 3, 10J). The spermathecae of Ibericancer sanchoi n. gen., n. sp. are large, ovate in shape and obliquely directed.

Remarks on abdominal holding. Casts of Dakoticancer overana examined and illustrated show a small protuberance on sternite 5 at the level of the socket on the ventral surface of pleomere 6 ( Fig. 3C View FIGURE 3 A – E ). A similar condition can be deduced from the abdomen of D. australis illustrated by Bishop et al. (1998: 243, fig. 1.8), where the presence of a socket is suspected below the produced latero-posterior angles of pleomere 6. An abdominal holding system, with a press button located on sternite 5 and an abdominal socket, is thus recorded for the first time in a podotreme crab. It is of the press button type, as in nearly all Eubrachyura Saint Laurent, 1980. A salient button for the same function is present in the Ibericancridae n. fam. ( Fig. 4A, D View FIGURE 4 A – E ). The press button of the Dakoticancroidea constitutes a robust synapomorphy of the superfamily among podotremes. The press button is not exclusive to the Eubrachyura since a socket (although not coupled with a typical “button”) also occurs in another podotreme group, the Lyreidinae Guinot, 1993 , among the Raninoidea De Haan, 1839. The “homolid press button” of the Homoloidea also consists of a socket on pleomere 6, but the corresponding prominence is located anteriorly on sternite 4.

Hypotheses on burrowing and carrying behaviour. Bishop et al. (1998) stated that evidence of burrowing by dakoticancrid crabs was equivocal. Although Dakoticancer overana has frequently been found associated with burrows, these were neither abundant nor large enough to have been their homes, so that the species was suggested not to have been an obligate burrower ( Bishop 1981). The presence of moulds of more than twenty specimens of D. australis (with articulated appendages and dislocated plastrons) preserved within boxworks in the Potrerillos Formation of Mexico, inferred to be exuviae ( Vega & Feldmann 1991), however, suggests that moulting within burrows did take place. Such a behaviour has also been hypothesised by Fraaije et al. (2008: 20) for a new albuneid (sand crab) from the Miocene of France, which was found within a large turritellid gastropod. Conversely, D. australis , from the Cárdenas Formation in east-central Mexico, is not found associated with burrows, and most specimens preserve articulated appendages. Vega et al. (1995) concluded that either these specimens were corpses or that the observed differences in preservation between the two Mexican assemblages resulted from different taphonomic histories. All Spanish specimens studied here are interpreted as moults. The pterygostomian plates are separated and are preserved slightly laterally displaced from the carapace. The proximal end of the first pleomere is disconnected from the thick posterior margin; this segment has fallen inside the carapace, and is preserved under an angle relative to the second pleomere. Another fact that does not fit a burrowing life is the supposed carrying behaviour inferred from the dorsal location and reduction of P5 ( Dakoticancridae ) or both P4 and P5 ( Ibericancridae n. fam.) ( Figs. 7A View FIGURE 7 A – C , 8D View FIGURE 8 A – D , 9A, C View FIGURE 9 A – C ). If the crab conceals itself by holding something (shell, sponge, algae) over its carapace, a burrow is unnecessary. As the dactyl of the leg used for carrying, which would be hooked or form a subchelate end to hold the object, is not preserved in the Dakoticancroidea, there is no proof of such a grasping by these pereiopods.

Our interpretation of functional morphology nevertheless provides a clear sign for camouflage by the hind leg(s) in dakoticancroid crabs, as in most other podotremes ( Guinot et al. 1995). It is a conservative behaviour actually found in all families with the exception of the extant Dynomenidae , which live in corals or on rocky bottoms ( McLay 1999), and of the Raninidae , which bury themselves in sand. Among the Cyclodorippoidea a carrying behaviour using sea urchin spines, pieces of shell and bits of seaweed has been noted for the Cyclodorippidae and Cymonomidae Bouvier, 1897 ( Garth 1946; Wicksten 1982; Tavares 1994). A carrying behaviour is probable, perhaps combined with a burying behaviour ( Guinot & Tavares 2001: 529) in the Phyllotymolinidae Tavares, 1998 , which similarly has reduced subchelate and mobile P4 and P5.

Avitelmessus grapsoideus View in CoL , a dakoticancrid with P5 probably quite contrasting to the thick and long P4, is an unusual crab on account of its large size (a giant among North American Cretaceous crabs) and its flattened and ornamented carapace. It was supposed to live “by tightly pressing its flattened body against the mud-sand bottoms” ( Bishop et al. 1998: 249), a behaviour perhaps not compatible with carrying behaviour. Pereiopods are not preserved in the small and highly sculptured Tetracarcinus View in CoL and in the poorly known Seorsus (see Bishop et al. 1998). In Ibericancer sanchoi View in CoL n. gen., n. sp. the reduction and dorsal position of the P4 and P5, which probably could have been positioned over the carapace, suggest the possibility of a carrying behaviour by both P4 and P5, similar to that found in extant Podotremata ( Guinot et al. 1995). The reduced P5 could have only been involved in a carrying behaviour among dakoticancrids. This was suggested for Dakoticancer overana View in CoL by Glaessner (1960). The thickness of the body, and the fact that the P4 and P5 are reduced, indicate that the Ibericancridae View in CoL n. fam. may have had a different mode of life than the Dakoticancridae View in CoL .

The Dakoticancroidea is, to our knowledge, one of the first fossil brachyuran groups in which a carrying behaviour may be inferred from reasonably certain morphological characters, that is, the last pereiopod(s) that are nearly entirely preserved. Fossil crabs with preserved last pereiopod(s) are rare and only a few homolids have so far been recorded (see Larghi 2004: 529). It is still a matter of conjecture to suppose that carrying behaviour was a regular phenomenon in fossil Homoloidea, as in extant representatives (as well as in extant homolodromioids) since the last pereiopods are very poorly preserved in fossil record. The Cenomanian Corazzatocarcinus Larghi, 2004 ( Larghi 2004: 530, figs. 2–4), assumed to belong to the Podotremata ( Vega et al. 2007), also shows clearly visible, subdorsal and reduced P4 and P5. Its assignment to a particular podotreme family is still problematic.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Ibericancer sanchoi

| Artal, Pedro, Guinot, Danièle, Bakel, Barry Van & Castillo, Juan 2008 |

Corazzatocarcinus

| Larghi 2004 |