Formicivora grantsaui, Gonzaga, Luiz Pedreira, Carvalhaes, André M. P. & Buzzetti, Dante R. C., 2007

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.176703 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5658465 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E62787D8-E66B-5C05-FF19-FEBAFC5CF915 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Formicivora grantsaui |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Formicivora grantsaui View in CoL sp. nov.

( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 )

Holotype. MNRJ 44149: adult male (skull 100% ossified; right testis 4.2 mm, left 3.6 mm) from the valley of the Rio Cumbuca (12o58’29”S, 41o21’29”W, elevation 860 m), 3.5 km northeast of the town of Mucugê, in the municipality of Mucugê, state of Bahia, Brazil; mist-netted 22 November 2002 by LPG and AMPC, prepared as a skin by LPG; carcass (including post-rostral skull) preserved in alcohol; molting feathers on body and head, plumage slightly worn. Calls tape-recorded by LPG ( ASEC 10614-10616). Flattened wing length 50 mm; tail length 59 mm; bill from anterior edge of nostril 8.5 mm; exposed culmen 12.5 mm; tarsus 19.5 mm; weight 9.0 g (light fat).

Paratypes. MNRJ 44150: adult female (skull ossified, well-developed egg in oviduct 16.1 mm x 11.5 mm) paired with holotype, same date and site, molting feathers on wing, tail, head and body, prepared as a skin; voice recordings ASEC 10614-10615. MPEG 60419: adult female (skull ossified, ovarium 5.7 mm, oviduct moderately developed) collected 14 November 2002, same site as holotype, molting feathers on tail, head and body, prepared as a skin. MPEG 60420: adult male (skull ossified, right testis 3.3 mm, left 4.1 mm), paired with MPEG 60419, same date and site, molting feathers on head and body, prepared as a skin. MZUSP 76676: adult male (skull ossified, right testis 2.8 mm, left testis 3.0 mm), collected 28 November 2002, same site as holotype, molting feathers on head and body, prepared as a skin; voice recording ASEC 10515. MZUSP 76677: adult female (skull ossified, ovarium 3.9 mm, oviduct not developed) paired with MZUSP 76676, same date and site, molting feathers on wing and breast, prepared as a skin.

Additional specimens (non-type material). MNA 2690 and MNA 2691 (spirit specimens): adult males, Serra do Ribeirão (12o33’30”S, 41o25’13”W, elevation 950 m), municipality of Lençóis, 17 and 19 February 1999; RG 2924 (skin): adult male, Igatu, municipality of Andaraí, 18 May 1965; UFRJ 0 798 (flat skin): adult male, Igatu, municipality of Andaraí, 16 November 2002; voice recordings ASEC 10541-10542.

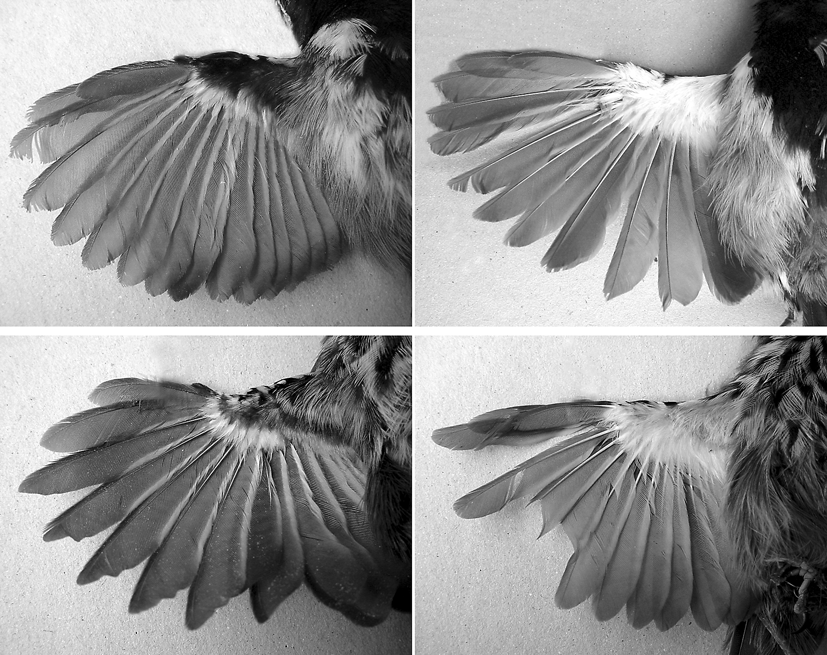

Diagnosis. Morphology and coloration. Females of the new species differ from those of F. littoralis , F. melanogaster and F. s e r r a n a by lacking a facial black mask and by having the sides of the head, throat, and breast whitish with black streaks (vs. no streaks). From F. acutirostris and F. erythronotos the new species differs by possessing 12 rectrices (vs. 10 in the former and 10 or 12 in the latter) with large (vs. absent or narrower) white tips and by the adult males having the sides of the head, throat, and breast black separated from upperparts by a white eyestripe continuing and broadening down the sides of the neck and breast (vs. no stripe). Both females and adult males of the new species differ from those of F. r u f a ( Figs. 3–5 View FIGURES 3 – 5 ) by having the flanks brown (vs. yellowish ochraceous), the upperparts darker and, more strikingly, by having the underwing-coverts grey and white (vs. entirely white, Figs. 6–7 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 ). From most recognized taxa in the F. g r i s e a complex the new species differs by the streaked (vs. plain) pattern of females, being similar in this respect to F. g. orenocensis, from which it differs by having the flanks brown (vs. white) and by having the outer rectrices edged white (vs. extensively white). F. grantsaui differs further from F. g r i s e a by possessing a longer tail (tail length> 105% wing length, vs. <100% wing length), similar to both F. acutirostris and F. r u f a.

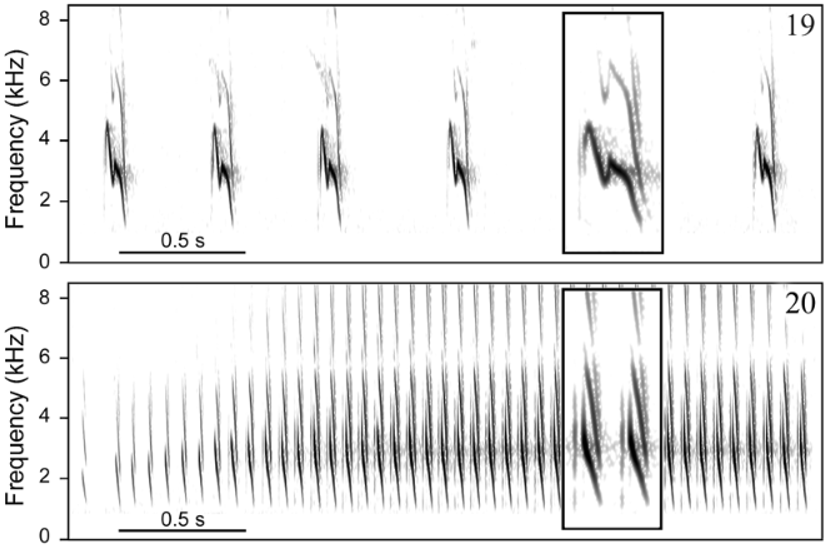

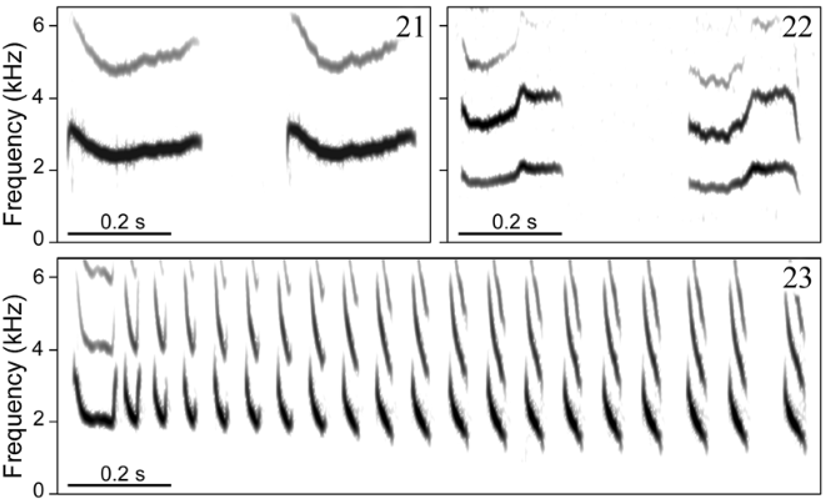

Vo ic e. Distinguished from all other taxa in the genus by having a two-part alarm call formed by more than two (rarely only two) notes. This call type has been hypothesized to be derived within Formicivora ( Gonzaga 2001) , contributing to define a clade that includes F. acutirostris , F. r u f a, and the F. g r i s e a complex ( Figs. 9– 12 View FIGURES 9 – 12 ). A very short and distinctively modulated territorial (duet) call also differentiates F. grantsaui from all other species in the genus. A homologous call has been recorded from F. g r i s e a and F. r u f a, showing a different sound structure in each of these species ( Figs. 15–18 View FIGURES 15 – 18 ), but it is apparently absent from the repertoire of the other species in this clade, F. acutirostris , possibly as a secondary loss ( Gonzaga 2001). Another striking diagnostic vocal character state between the new species and F. r u f a is the pace of the loudsong, which is much slower in F. grantsaui (c. 2 notes/s vs. c. 14 notes/s; Figs. 19–20 View FIGURES 19 – 20 ); as in F. acutirostris , these notes do not form phrases with a stereotyped duration such as those of the loudsong of F. r u f a. Furthermore, the new species differs from F. r u f a and other species of the genus by its distress call, which is a series of a few weak whistles (vs. a sharp trill). A similar distress call has been recorded also in F. g r i s e a ( Figs. 21–23 View FIGURES 21 – 23 ).

Description. Adult males: crown, back and rump Verona Brown (223B), frontal feathers greyish. Crown feathers darker along rachides, giving it a slightly streaked appearance. No interscapular patch. Sides of head (including lores) and underparts from chin to belly black, bordered by a white stripe going down from above the lores to the sides of the belly through the sides of neck and breast. Posterior portion of belly and crissum grey. Flanks Sayal Brown (223C). Wing feathers Vandyke Brown (121), inner webs with whitish edges. Upper wing-coverts black with white terminal spots. Underwing-coverts dark grey in the basal two-thirds, white in the distal third. Tail feathers with white tips that are narrower (c. 2 mm in fresh plumage) in the central feathers and increasingly broader (up to c. 5 mm) towards the outer feathers; white on the tips of the two outer pairs of tail feathers extending along the edge of the outer webs ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ). Upper surface of tail feathers Vandyke Brown (121), becoming darker towards the tip. Under surface of the tail feathers (especially the outer ones) two-toned, grey with a broad black subterminal band ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ). Females: differ from males by having upperparts slightly paler than males, Raw Umber (23) instead of Verona Brown (223B), and sides of the head and underparts white with black streaks (c. 2 mm wide on chest). Tail composed of 12 rectrices, strongly graduated (outer rectrices 38%–47% shorter than central ones).

Coloration of soft parts in life. irides brown; bill black (basal half of mandible grey in females), palate and tongue orange; tarsi and toes plumbeous-grey, soles yellowish.

Morphometry. See Table 1 View TABLE 1 .

Males Females Vocalizations. Alarm or contact call. This call ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 9 – 12 ) is usually delivered when a bird is apparently alarmed or trying to re-establish contact to its mate. It is typically repeated at short intervals (range = 0.6– 3.0 s, mean = 1.13 s, SD = 0.39, n = 147 calls from at least 5 birds) forming a long series that may contain 47 or more consecutive calls at an average delivery rate of 0.75 calls/s (range = 0.61–0.95, SD = 0.11, n = 7 series from at least 5 birds). The first part of this two-parted call is formed by a single note, and the second part most often (93%, n = 286 calls from at least 7 birds) presents two notes, rarely one or three ( Figs. 13–14 View FIGURES 13 – 14 ). These infrequent variant calls are mixed in among a series of more typical (three-noted) calls given by an individual, not given in independent series by different individuals. Three-note calls have an average duration of 0.26 s (range = 0.2– 0.3 s, SD = 0.02, n = 188 calls from at least 6 birds) and an average “max frequency” of 3.4 kHz (range = 3.1–4.4 kHz, SD = 0.23, n = 194 calls from at least 6 birds), being noticeably the sharpest voice of the repertoire. On one occasion, a female-plumaged bird that approached the observer in response to tape playback delivered a series of these calls in which the last note of each call was prolonged in a harsh sound that was like a short version of scolding calls ( Fig. 24 View FIGURES 24 – 25 ). This transitional series was followed without interruption by a series of purely harsh and longer scolding calls (see below), after which the bird stopped calling and departed.

Territorial duet call. This pair duet ( Fig. 15 View FIGURES 15 – 18 ) is often delivered at the end of a song bout, but may also take place as an isolated series of calls. Up to 9 calls have been recorded in a sequence (range = 3–9, n = 8). Each call is a very short syllable composed of two or three notes, most often (63%, n = 57 calls from at least 8 birds) three notes, with an average duration of 0.1 s (range = 0.08– 0.13 s, SD = 0.014, n = 63 calls from at least 8 birds) and an average “max frequency” of 3.0 kHz (range = 2.6–3.9 kHz, SD = 0.26, n = 63 calls from at least 8 birds). Sometimes, the call seems to be composed of only one note with three linked parts, each of these with a deep ascending/descending modulation in both frequency and amplitude. Whichever the case, the highest frequency always occurs in the middle (or second note) of the call.

Loudsong (sensu Willis 1967). As in the other species of the genus ( Gonzaga 2001), the loudsong of F. grantsaui ( Fig. 19 View FIGURES 19 – 20 ) is a steady repetition, with occasional hesitations (i.e. occasional lengthened intervals between notes), of very short notes (<0.1 s) with a sharp descending frequency modulation. In F.grantsaui , the notes have an average duration of 0.07 s (range = 0.06– 0.08 s, SD = 0.006, n = 507 notes from at least 8 birds), an average “max frequency” of 3.1 kHz (range = 2.6–3.6 kHz, SD = 0.15, n = 507 notes from at least 8 birds) and are uttered in a deliberate way, at an average pace of 2.1 notes per second (range = 1.5–2.7, SD = 0.35, n = 31 series from at least 8 birds). Bandwidth of each note is about 3.0 kHz, with an average highest frequency of 4.4 kHz (range = 3.8–5.2 kHz, SD = 0.26) and an average lowest frequency of 1.4 kHz (range = 1.1–1.8 kHz, SD = 0.12, n = 507 notes from at least 8 birds). In all but one of 8 individuals recorded, the notes show a rapid inflection at the middle. A recording made by B. M. Whitney at Morro do Pai Inácio that appeared in a CD publication ( Isler & Whitney 2002) as one of the two included examples of the loudsong of F. r u f a is, in fact, a sample of the loudsong of F. grantsaui .

Distress call. This call ( Fig. 21 View FIGURES 21 – 23 ) was recorded from birds handled after capture in mist-nets. It consists of a very soft whistle with a rapid attack and a descending/ascending frequency modulation, around an average “max frequency” of 2.58 kHz (range = 2.3–3.1 kHz, SD = 0.20, n = 103 notes from 2 birds) and an average duration of 0.27 s (range = 0.2– 0.4 s, SD = 0.04, n = 103 notes from 2 birds). It is usually delivered in groups of 2–5 calls, rarely more (n = 37 call groups from 2 birds), at irregular intervals that apparently depend on the level of discomfort of the bird.

Scolding call. This call ( Fig. 25 View FIGURES 24 – 25 ) was recorded from both adult males and female-plumaged birds as they approached the observer in response to playback. As with the alarm call, it may be delivered in a long series with up to 16 or more consecutive calls, at an average delivery rate of 0.7 calls/s (range = 0.3–1.1, SD = 0.3, n = 8 series from at least 3 birds). Each call has an average duration of 0.56 s (range = 0.4– 0.9 s, SD = 0.08, n = 99 calls from at least 3 birds) and an average “max frequency” of 4.6 kHz (range = 3.4–6.0 kHz, SD = 0.61, n = 99 calls from at least 3 birds). The interval between consecutive calls is quite variable (range = 0.2– 5.1 s, mean = 1.2 s, SD = 1.04, n = 90 calls from at least 3 birds). The harsh sound of this voice results from a periodic modulation in both amplitude and frequency of the carrier, which is represented in the narrow-band audiospectrogram as a series of sidebands, each looking like a zigzag horizontal line, and in the broad-band spectrogram as a series of broad-band frequency vertical lines. A similar call was recorded from F. grisea near Santo Amaro, Bahia, Brazil ( Fig. 26 View FIGURE 26 ), but it seems not to be commonly delivered by any other species of the genus, at least not as frequently as it seems to be by F. grantsaui .

Geographic range. The new species is known thus far only from the Serra do Sincorá, on the eastern escarpments of the Chapada Diamantina , Central Bahia, eastern Brazil (for a general description and bird list of this region, see Giulietti et al. 1997 and Parrini et al. 1999). In this range, F. grantsaui has been documented by specimens or voice recordings from several sites between 850 m and 1100 m at four localities, although it certainly occurs more extensively within the area bounded by these records ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 ): Morro do Pai Inácio, in the municipality of Palmeiras; the valley of the Rio Ribeirão, in the municipality of Lençóis; Vale do Paty and near Igatu, both in the municipality of Andaraí; and the valley of the Rio Cumbuca and other sites around the town of Mucugê.

Currently, only F. melanogaster has been recorded further north of Morro do Pai Inácio, in the Morro do Chapéu region ( Naumburg 1939, Parrini et al. 1999), and south of Mucugê, near the town of Ibicoara ( Parrini et al. 1999), and only F. r u f a was documented further west (specimen from Rio de Contas: MNRJ 39000 and voice recordings by R. Parrini from the nearby Pico das Almas). Our survey of the Chapada Diamantina in November 2002 also included a brief search for the new species north of Lençóis (using tape playback) but, as did previous workers, we found only F. melanogaster there, near Morro do Chapéu.

Habitat and ecological segregation. The new species inhabits primarily the campo rupestre vegetation occurring on the rocky outcrops above 800 m of elevation on the slopes of stream valleys or high plateaus and at exposed ridges ( Fig. 27 View FIGURE 27 ). This landscape is composed of ancient Precambrian sandstones and conglomerates, eroded and dissected by water; soils are thin and nutrient-poor, with acid sands mixed with black peat ( Harley & Giulietti 2004). A century and more ago, the Chapada Diamantina was an important area in Brazil for diamond and gold extraction. Most of the area was converted to a National Park in 1985 and the economy is slowly shifting to ecotourism ( Funch 1999). Although vegetation may be recovering from past disturbance from mining activities and direct exploitation ( Harley & Giulietti 2004), fire is a major permanent threat ( Funch 1999).

Characteristic plants of the campo rupestre near the type-locality (Mucugê) are the stemless palm Syagrus harleyi (Palmae) , the “canelas-de-ema” Vellozia spp. ( Velloziaceae ), the “imbé” Philodendron saxicolum (Araceae) , the “mocó” Clusia burlemarxii (Guttiferae) , Lychnophora spp. (Compositae), Calliandra spp. (Leg. Mimosoidea), Verrucularia glaucophylla (Malpighiaceae) , Marcetia taxifolia and many other members of its family ( Melastomataceae ), the bottle cactus Stephanocereus luetzelburgii (Cactaceae) , the grasses Eragrostis petrensis and Panicum sp. ( Gramineae ), everlastings ( Eriocaulaceae ), terrestrial orchids ( Orchidaceae ) and bromeliads ( Bromeliaceae ), myrtles ( Myrtaceae ), the “flecha” Lagenocarpus rigidus (Cyperaceae) , and the “feijão-seco” Humiria balsamifera var. parvifolia (Humiriaceae) ( Harley & Giulietti 2004).

Other birds occurring with F. grantsaui in this habitat are: Phaethornis pretrei (Lesson & Delattre) , Chlorostilbon aureoventris (d´Orbigny & Lafresnaye), Augastes lumachella , Thamnophilus torquatus Swainson , Polystictus superciliaris (Wied) , Elaenia cristata Pelzeln , Schistochlamys ruficapillus (Vieillot) , Gnorimopsar chopi (Vieillot) , Saltator atricollis Vieillot , Sicalis citrina Pelzeln , Zonotrichia capensis (Müller) , and Embernagra longicauda Strickland.

In November 2002, we found that F. r u f a may be locally sympatric with F. grantsaui . Around Mucugê, pairs of F. r u f a were common at the cerrados (locally known as “campos gerais”, Harley & Giulietti 2004, p. 106) in flatter areas with lateritic soils mixed with sand west of the Serra do Sincorá, along the dirt road to the town of Palmeiras ( Fig. 28 View FIGURE 28. C ), and some apparently isolated males were recorded in the valley of the Rio Mucugê, just south of the town, an obviously very disturbed area. One of these males was singing within hearing distance of at least one female-plumaged F. grantsaui , which we found slightly higher up on a rocky slope. An apparently permanent ecological segregation exists between F. r u f a and F. g r i s e a when they occur in sympatry ( Sick 1955, Silva et al. 1997, Gonzaga 2001), and it would be expected to exist also in the Chapada Diamantina between F. r u f a and F. grantsaui .

Nomenclature. Once it was demonstrated that the birds found in the campos rupestres of the Serra do Sincorá are not the same taxon as what is currently known as Formicivora rufa (e.g. Zimmer & Isler 2003), from which they are clearly diagnosable by plumage coloration, vocalizations and preferred habitat, it became important to determine the identity of the syntypes of Myiothera rufa Wied, 1831 , which were collected at unspecified localities in the interior of Bahia (“aus den inneren Gegenden der Provinz Bahiá”: Wied 1831, p. 1098; see also Allen 1889, LeCroy & Sloss 2000). These specimens were examined at our request by M. LeCroy and subsequently also by AMPC and S. Kenney, to rule out the possibility that this name could be applied to the taxon we are describing here.

Any decision based on the general coloration of the types of M. rufa could be flawed, given the possibility that their colors have faded owing to the long exposure to light that Maximilian specimens have suffered (cf. Allen 1889) and given that the streaking of underparts is subject to much variation in F. r u f a, as discussed by Pinto (1940, 1947). For these reasons, the most useful diagnostic character is the coloration of the underwingcoverts, which are grey and white in both sexes of one species, and white in both sexes of the other. Based on this premise, the syntypes were checked with an special attention paid to this feature. Both specimens, which are quite rufescent, have the underwing-coverts white ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ), which makes them distinct from the birds we described here, and is in full agreement with the original description of M. rufa , in which it is stated that the anterior part of the wing, as well as the underwing-coverts, are white (“vorderer Flügelbug weiss, eben so die inneren Flügeldeckfedern”: Wied 1831, p. 1097). M. LeCroy (in litt. to LPG 2003), informed us that “unfortunately, the wings of both specimens have been glued on with huge globs of glue that make it difficult to see the underwings (...). However, I have done my best to pull the feathers loose from the worst of the glue and I see no indication of any dark feathers in the underwing-coverts. They appear all white, even though stuck together.” One of the few authors to have reported the presence of white underwing-coverts in F. r u f a was Zimmer (1932), in his detailed description of F. r. urubambae from Peru. It is not clear, however, if he also considered this character when examining the types of M. rufa . Most of modern descriptions of F. r u f a in the ornithological literature do not mention this feature.

The conclusion that Wied's syntypes belong to the species currently recognized as F. r u f a is also supported by the fact that all the localities visited by Wied in the interior of Bahia, where he might have collected the syntypes of M. rufa , lie more than 100 km to the south of the Chapada Diamantina , betwen the upper courses of Rio Pardo and Rio Gavião, close to the border between Bahia and Minas Gerais (cf. Bokermann 1957). Despite an apparently ill-informed claim that these specimens “never came from Bahia” (Hellmayr in Naumburg 1939), Naumburg (1939) concluded, “after a thorough study [of coloration patterns], that the types of M. rufa came from Minas Geraes border of Bahia”, in agreement with Zimmer (1932), who stated that “if these types are truly from Bahia they must be from some extreme southern locality”. Pinto (1940, 1947) concluded the same. There seems to be no reason to doubt that the syntypes of M. rufa were collected by Wied during his sojourn in the interior of Bahia, and that he never reached the known range of F. grantsaui (see Bokermann 1957).

As evidently have our predecessors (e.g. Cory & Helmayr 1924, Zimmer 1932, Pinto 1936, 1940, 1947, Naumburg 1939), we have assumed that Wied’s types of Myiothera rufa are adult females. The possibility has been raised, however, that they might be immatures and that “it is possible that the underwing-coverts would be light, then become dark when adult” (B.Whitney in litt. 2007). Although this entirely hypothetical speculation cannot be categorically disproved in the absence of known immature specimens of F. grantsaui , it is highly unlikely 1) that such an anomalous molt sequence would actually exist; 2) that both of the syntypes of M. rufa would be immature birds; 3) that immature birds from the campos rupestres of the Serra do Sincorá would prove to have entirely white underwing-coverts and still be similar in every other aspect to the syntypes of M. rufa ; and 4) that what we have named F. grantsaui occurs (or occurred) outside the Chapada Diamantina in the localities visited by Wied in the interior of Bahia or, conversely, that he somehow obtained specimens from the campos rupestres of the Serra do Sincorá by other means. Therefore we prefer the most parsimonious hypothesis, which is that Wied's syntypes represent the taxon that has traditionally been associated with the name Formicivora rufa .

Systematics and biogeography. The Espinhaço Range has been regarded as an unparalleled area of endemism in eastern South America for vascular plants ( Giulietti et al. 1997), and also holds a number of endemic birds ( Bibby et al. 1992) and other terrestrial vertebrates (e.g. lizards, Rodrigues 1988). From a biogeographic point of view, the endemic avifauna of the Espinhaço Range seems to be composed of several distinct elements, as its taxa have their putative closest relatives in the Amazonian lowlands, the Guianan plateaus, or the Andean highlands. However, phylogenetic hypotheses based on parsimony analysis of morphological, molecular and ecological data that could provide a basis for biogeographic hypotheses of vicariance do not exist for most genera of Neotropical birds and plants, and the Espinhaço endemic taxa are no exceptions, which prevents any further advance in the understanding of possible past connections between those areas and the Espinhaço Range. Similarly, it is not possible to propose any hypothesis of evolutionary history for F. g r a n t - saui, as its position in the group that encompasses its closest relatives ( F. acutirostris , F. g r i s e a, and F. r u f a) is not known, pending a phylogenetic analysis that should ideally include samples of the entire F. g r i s e a species complex and several populations of F. r u f a.

Endemic bird taxa whose proposed sister relatives occur in the north of the continent are four hummingbirds: Campylopterus largipennis diamantinensis Ruschi , Colibri delphinae greenewalti Ruschi , and Augastes spp. It is noteable that speciation has taken place along the Espinhaço Range itself within the genus Augastes , its two allospecies replacing one another in the more or less disjunct northern and southern portions of this geological complex ( A. lumachella and A. scutatus Temminck , respectively). The presumed closest relative of these species is Schistes geoffroyi Bourcier , from the Andes ( Sick 1993, Schuchmann 1999). Relationships of the canastero Asthenes luizae Vielliard are not certainly known but possible close relatives occur in the southern part of continent and in the Andes ( Sick 1993, Remsen 2003). It is worth pointing that A. lumachella , C. d. greeenewalti and F. grantsaui are restricted to the northern portion of the Espinhaço Range, the other three endemic taxa being restricted to its southern portion.

Polystictus superciliaris View in CoL and Embernagra longicauda share the main part of their geographical and ecological distributions along all the Espinhaço Range, where they are typical of the campo rupestre ( Parrini et al. 1999). However, neither species can longer be considered endemic to this mountain complex because they also have been recorded from other mountain ranges ( Vasconcelos et al. 2003).

Etymology. We are pleased to name this new species after Rolf Grantsau, who first noticed its distinctiveness, and in recognition of his contributions to the study of Brazilian birds. As common names for this species we propose Sincorá Antwren (English) and Papa-formigas-do-Sincorá (Portuguese), referring to the type locality region, the Serra do Sincorá in the Chapada Diamantina .

TABLE 1. Morphometric data of specimens of Formicivora grantsaui.

| MNA | MNA | MNRJ | MPEG | MZUSP | RG | UFRJ | MNRJ | MPEG | MZUSP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2690 Wing length a 51 | 2691 52 | 44149 50 | 60420 52 | 76676 50 | 2924 53 | 0 798 52 | 44150 51 | 60419 50 | 76677 49 |

| Tail length a 60 | 56.5 | 59 | 61 | 54 | 58.5 | 60.5 | 59 | 57.5 | 57 |

| Length difference between 28 central and outer rectrices a | 25 | 27 | 23 | 21 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 22 | 24 |

| Bill length a (from nostril) 8.5 Culmen length a 13.5 | 8.5 13 | 8.5 12.5 | 9 13.5 | 8.5 12.5 | 9 13.5 | 8.5 13 | 8.5 12.5 | 8.5 12.5 | 8.5 12.5 |

| Tarsus length a 19 | 19 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 20.5 | 20 | 19 |

| Weight b - | - | 9.0 | 9.1 | 8.5 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 11.5 | 10.5 | 9.5 |

| a mm; b grams. |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |