Hyalinobatrachium cappellei

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.200895 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5658431 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/E57687EB-FFA5-5F15-F3A6-E27BFA3C148C |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Hyalinobatrachium cappellei |

| status |

|

Hyalinobatrachium cappellei View in CoL

( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 )

Hylella cappellei View in CoL van Lidth de Jeude, 1904: 94, bona species. Centrolenella cappellei Noble, 1926: 18 .

Centrolenella fleischmanni Goin, 1964: 1 View in CoL .

Cetrolenella taylori Lescure, 1975: 390 .

Centrolenella taylori Hoogmoed and Avila-Pires, 1990 .

Hyalinobatrachium crurifasciatum Myers and Donnelly, 1997: 9 View in CoL , new synonym. Hyalinobatrachium taylori Lescure and Marty, 2000: 78 View in CoL .

Hyalinobatrachium eccentricum Myers and Donnelly, 2001: 16 View in CoL , new synonym. Hyalinobatrachium ignioculus Noonan and Bonett, 2003: 92 View in CoL , new synonym. Hyalinobatrachium View in CoL sp2 Ernst et al. 2005: 183.

Hyalinobatrachium igniocolus Barrio-Amorós and Castroviejo-Fisher, 2008: 235 , lapsus calami. Hyalinobatrachium aff. ignioculus Guayasamin et al. 2008a: 580 View in CoL .

Type locality. River Saramacca and neighboring areas, Suriname.

Diagnosis. (1) Dentigerous processes on vomer and vomerine teeth absent; (2) snout truncate in dorsal and lateral view; (3) tympanum covered by skin, not visible through skin; (4) dorsal skin shagreened in life and preservative; (5) presence of small cloacal enameled warts; (6) parietal peritoneum transparent, pericardium from completely transparent to totally white with intermediate states, visceral and hepatic peritonea white, all other peritonea transparent; (7) liver bulbous; (8) humeral spine absent; (9) webbing formula of fingers III (2– – 2+) – (2 – 2+) IV; (10) webbing formula of toes I (1 1/3 – 1 1/2) – (2+ – 1 1/3) II (1+ – 1 1/3) – (2 1/3 – 2 1/2) III (1+ – 1 1/2) – (2 1/2 – 2 3/4) IV (2 3/4 – 3–) – (1 – 1+) V; (11) low and weakly enameled ulnar and tarsal folds; (12) nuptial excrescences Type-V composed of a cluster of glands and situated in the medial, dorso-lateral internal side of Finger I, glands not present in other fingers, prepollex not evident from external view; (13) Finger I longer than Finger II; (14) eye diameter larger than width of disc on Finger III; (15) coloration in life: dorsum with yellow or pale green spots set in a light green reticulum dotted with dark small and/or minute melanophores, when the yellow spots on the hind limbs are sufficiently big they give a pattern of crossbars, bones white; (16) coloration in preservative: dorsum cream with purple melanophores, spots and crossbars on hind limbs may be lost; (17) iris golden with dark melanophores, with or without a complete or not complete ring (from brown to light red) around the pupil, pupillary ring could be partly or completely absent in some specimens; (18) minute melanophores not extending throughout fingers and toes except on the base of Finger IV and Toe V; in life, tip of fingers and toes white; (19) advertisement call composed by a single pulsed note lasting 0.13– 0.29 s, dominant frequency of 3926.6–5081.8 Hz, males call from the underside of leaves; (20) fighting behavior unknown; (21) egg clutches deposited on the underside of leaves, males often on the same leaf than eggs; (22) tadpole with sinistral spiracle on the posterior third of the body, short vent tube; (23) medium size adult males, SVL = 18.6–24.9 (21.8 ± 1.4, N = 30) mm and one female 21.3 mm.

Comparisons. The following unique combination of phenotypic characters differentiates Hyalinobatrachium cappellei from all other species in the genus: snout truncated in dorsal and lateral views, tympanic membrane and annulus not appreciable in life, pericardium from completely transparent to totally white with intermediate states, hand weebing formula III (2- – 2+) – (2 – 2+) IV, dorsal coloration in life yellow big spots on a light green reticulum dotted with small and/or minute melanophores, dorsal coloration in preservative pale cream dotted with small and/or minute melanophores surrounding big cream spots (could be lost in some specimens), iris coloration in life yellow with brown-red flecks and a red-brown ring (complete or not) encircling the pupil, light yellow pupillary ring from absent to complete, bones in life white, coloration of hands and feet in life white, and a single pulsed note advertisement call with frequency modulation (increasing and decreasing within each pulse giving the shape of a saw), lasting 0.13– 0.29 s and with a dominant frequency of 3926.6–5081.8 Hz.

Morphological, bioacoustic and genetic evidences allowing the differentiation between Hyalinobatrachium cappellei and all other species of Hyalinobatrachium from the GS are summarized in Figures 2 View FIGURES 2 , 3, 4 and Tables 1, 3.

Remarks. This is the most common and ubiquitous species of Hyalinobatrachium in the GS. The historical circumstances of the holotype combined with the intraspecific variability of some characters have led to a confusing taxonomic situation. The species was described based on a single specimen from Suriname (van Lidth de Jeude 1904). The original description lacks essential details and is very rudimentary; furthermore, the holotype is not very well preserved. Before any other species of Hyalinobatrachium was described or cited for the GS, Goin (1964) considered H. cappellei as a junior synonym of H. fleischmanni . Unfortunately, this implied that till recently ( Noonan & Harvey 2000; Cisneros-Heredia & McDiarmid 2007; Kok & Castroviejo-Fisher 2008), other authors have overlooked this species name. We have shown that H. cappellei is different from H. fleischmanni in various qualitative morphological traits and revalidate the name. Biogeographic patterns of centrolenid species also support the idea that they constitute different and independently evolving lineages. To the best of our knowledge, the holotype of H. cappellei was the last remaining vouchered specimen from a locality east of the Andes assigned to H. fleischmanni . Otherwise Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni is restricted to Central America and the Pacific coast of Colombia and Ecuador and it is separated from the Guiana Shield by the Andes, which is an important barrier for glassfrogs (Guayasamin et al. 2008a). No other centrolenid species is known to occur on lowlands at both versants of the Andes. Our taxonomic results reconcile this biogeographic conundrum.

In addition, we could not find evidences of lineage divergence among H. crurifasciatum , H. eccentricum , H. ignioculus , and H. cappellei . Thus we consider them to be the same biological entity. According to the principle of priority ( ICZN 1999) we use the name Hyalinobatrachium cappellei . Below we provide a detailed discussion of why the characters used in the original descriptions to diagnose these species are not valid.

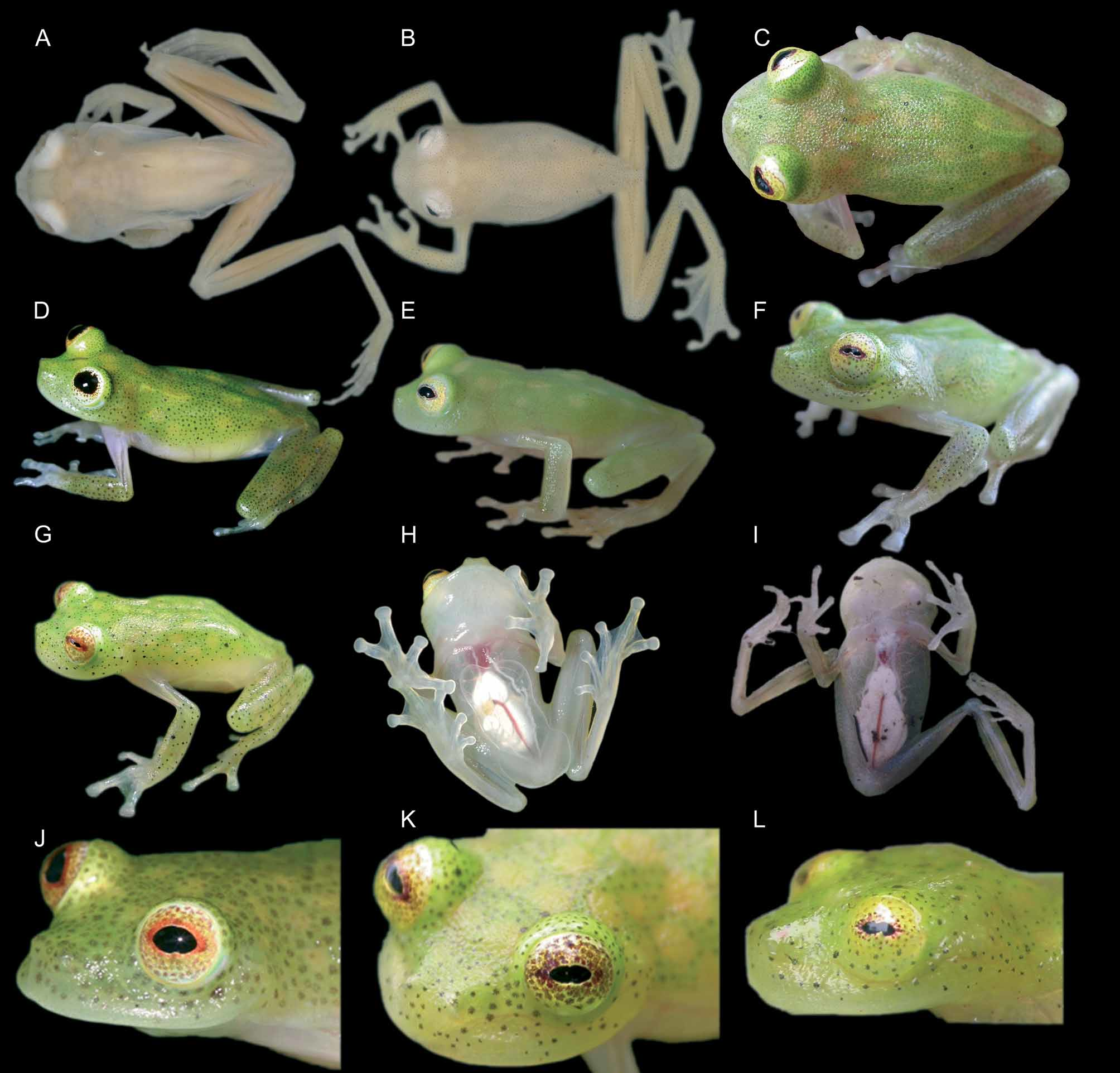

When Myers and Donnelly (1997) described Hyalinobatrachium crurifasciatum , they emphasized the fact that the pericardium is partially transparent ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 I), the iris yellow ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 K) and the nuptial excrescence of Type-I ( Flores 1985). In Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005), the taxonomy of the species was evaluated. Following the original description and after the examination of type material and 35 new specimens from different localities, they concluded that the species is distributed basically throughout the entire Guiana Shield Highlands and some uplands of Venezuela, the pericardium was reported to be either totally transparent or completely white with intermediate states ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 H–I; see also Guayasamin et al. 2006: Fig. 14), SVL = 19.0–24.0 mm in males and 22.1–22.8 mm in females, and the nuptial excrescence Type-I is associated with glands (as described in Ayarzagüena 1992: Fig. 5 View FIGURES 5 B). However, Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005) did not provide any comment on H. ignioculus , a similar species from a close locality in Guyana described two years before.

Noonan and Bonett (2003) described Hyalinobatrachium ignioculus from the uplands of Guyana. According to the original description of H. ignioculus , the species can be separated from H. crurifasciatum by (characters of the former in parentheses): green limb bands in life present (absent); absence of a reddish ring around the pupil (present); smooth skin on the dorsum in preserved specimens (pustulated); nuptial excrescences Type-I (Type-II); and adult size in males SVL = 22.0–24.0 mm (20.8–23.0 mm). Although Noonan and Bonett (2003) stated that the pericardium of H. crurifasciatum is white, the original description presented it as partially transparent while white in H. ignioculus .

Later, Cisneros-Heredia and McDiarmid (2007) and Kok and Castroviejo-Fisher (2008) suggested that both species might be conspecific. Barrio-Amorós and Castroviejo-Fisher (2008) reported Hyalinobatrachium ignioculus for Venezuela, described its advertisement call, and restricted the morphological differences with H. crurifasciatum to the presence of a reddish ring around the pupil and males not larger than 23.0 mm.

When comparing the published data and the new data from this study, we observed that the five qualitative morphological characters (pupil coloration, pericardium, nuptial excrescences, green limb bands, dorsal skin texture, and differences in SVL) used by Noonan and Bonett (2003) to separate Hyalinobatrachium ignioculus from H. crurifasciatum represent either continuous variations with intermediate states or descriptive lapses. Moreover, different combinations of characters states were present in different individuals.

Pupil coloration has been used as the key character to separate Hyalinobatrachium ignioculus from H. crurifasciatum . However, our field observations show that this character varies in color and intensity between individuals (Table 1 and Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 D–G, 4J–L; see also Barrio-Amorós & Castroviejo-Fisher 2008: Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 ) and even the same specimen can change ring size and color intensity when exposed to light or if disturbed. Subsequently, the presence or absence of a red-brown ring around the iris cannot be used to separate these species.

Although the pericardium of H. ignioculus was described as white, the authors pointed out that, in some specimens, small portions of the heart appear reddish after 18 months of preservation and visible through the ventral surface. The paratype of H. ignioculus studied here showed this pattern, which was also observed in type material of H. crurifasciatum . However, we are not aware of any similar preservation artifact in other specimens of H. crurifasciatum . The transparency of the pericardium has therefore to be considered a continuous trait for both taxa with intermediate states (Table 1, Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 H–I) and cannot be used to distinguish between them.

All the males examined had nuptial excrescences composed of a group of glands (more or less evident) as described in Ayarzagüena (1992: Fig. 5 View FIGURES 5 B), Myers and Donnelly (2001), and Type-V of Cisneros-Heredia and McDiarmid (2007). After careful examination of this character, we concluded that the nuptial excrescences Type-II described for H. ignioculus by Noonan and Bonett (2003), and Type-I for H. crurifasciatum according to Myers and Donnelly (1997) and Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005) cannot be considered different character states, but just different terminology for the same character. This implies that the type of nuptial excrescences is an invalid character to separate H. ignioculus from H. crurifasciatum . However, the ability to observe nuptial excrescences varies dramatically with the preservation state and the sexual activity of the specimens, and in some cases these structures are not evident.

Green limb bands are the product of the dorsal coloration pattern exhibited by H. crurifasciatum and H. ignioculus (yellow or pale green spots in life set in a light green reticulum dotted with dark small and/or minute melanophores) so that when the yellow spots on the hind limbs are sufficiently big they give a pattern of crossbars. Compare Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 C–E (specimens without crossbars) with Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 G (crossbars present). Furthermore, the presence or absence of these crossbars has been observed in both species ( Barrio-Amorós & Castroviejo-Fisher 2008; this work); hence, this character is also of no utility to differentiate the species.

Texture of dorsal skin varies in both species from slightly shagreened to shagreened ( Barrio-Amorós & Castroviejo-Fisher 2008; this work). Moreover, this character is very sensitive to preservation conditions ( Kok & Castroviejo-Fisher 2008) and in some species of glassfrogs has been shown to vary with reproductive condition ( Harvey & Noonan 2005).

The differences in SVL between H. ignioculus and H. crurifasciatum in the study of Noonan and Bonett (2003) seems to be an artifact due to i) the small sample size of H. crurifasciatum (N=3) in their study; ii) the paratype of H. crurifasciatum was the biggest individual found so far (SVL= 24.0 mm); and iii) only two populations were compared, so variability of the species across its distribution was not portrayed. When comparing the data compiled for this work, SVL completely overlapped for males of both species: H. ignioculus (N= 13), SVL= 18.6–23.1 mm; H. crurifasciatum (N= 6), SVL= 20.3–24.7 mm.

Hyalinobatrachium eccentricum View in CoL was described by Myers and Donnelly (2001) for Cerro Yutajé, Amazonas, Venezuela. It is very similar in morphology and vocalizations to H. crurifasciatum View in CoL and H. ignioculus View in CoL and is only differentiated by the presence of an “ iris bicolored with a brown circumpupillary zone concealing a pupil (pupillary ring absent) and a golden yellow peripheral zone with grey flecks ” and “ nuptial excrescences not distinctively pigmented (not white), comprised of a gland of cells (barely discernible in the holotype) along edge of thenar tubercle on medial base of thumb and distally expanded as a larger and more evident patch of cells on dorsomedial surface of third joint ” ( Myers & Donnelly 2001: 16–17) and a “group of glands” in the area behind the tympanum which resemble the ones in the hands ( Señaris & Ayarzagüena 2005). Careful examination revealed that none of these characters allow separating species. The nuptial excrescences correspond to Type-V (see above) and the “group of glands” in the area behind the tympanum appears in several individuals of H. crurifasciatum View in CoL (a character that was overlooked, J. Celsa Señaris personal communication to SCF, and that we have observed in males of H. crurifasciatum View in CoL and H. ignioculus View in CoL ). This type of glands seems to depend on the sexual status of the individual and its preservation. The “ iris bicolored with a brown circumpupillary zone concealing a pupil (pupillary ring absent) and a golden yellow peripheral zone with grey flecks ” represents a extreme character state in a continuum: from absence of a colored ring with presence of a pupillary ring to presence of a circumpupillary zone with absence of pupillary ring (see Table 1 and Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 D–G, 4J–L). Moreover, two specimens, one from the summit of Auyan-tepui, Bolivar, Venezuela and another from French Guiana lowland rainforest ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES 4 D, L; see also Barrio-Amorós & Castroviejo-Fisher 2008: Figs 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2 View FIGURES 2 for other specimens coming from Venezuela) presented exactly the same kind of iris as described for H. eccentricum View in CoL , even lacking the pupillary ring (a novel trait for frogs following Myers & Donnelly 2001), refuting the idea that this phenotype corresponds to an endemic from the northwestern tepuys. Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005), after examining the holotype of H. eccentricum View in CoL , concluded that it is exactly identical to other specimens of H. crurifasciatum View in CoL except for having a dark brown iris. However, they assigned two individuals from Cerro Guanay (Bolívar, Venezuela), which present dark brown iris, to H. crurifasciatum View in CoL , due to their doubts about the authenticity of H. eccentricum View in CoL as a valid species. Our bioacoustics and genetic analyses are congruent with the morphological results presented here.

Biology and tadpole. Data on the number of eggs per clutch is provided in Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005). Position of calling males and amplectant pairs in Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005), Myers and Donnelly (1997; 2001) and Noonan and Bonett (2003). Lescure and Marty (2001) and Ernst et al. (2005) report proximity of males to egg clutches. The authors have observed males resting nearby egg clutches during the day in Quebrada Jaspe, Bolivar, Venezuela. In general, males vocalize underneath leaves (but some individuals have been observed on the upper side of leaves at the beginning of calling activity), 1–5 m above the water, and very often close to one or more clutches of eggs (presumably belonging to the same male). Clutches from 12 to 26 eggs are always on the underside of leaves. Advertisement call has been described in Myers and Donnelly (1997; 2001), Lescure and Marty (2000), Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005), Barrio-Amorós and Castroviejo-Fisher (2008), and this work (Table 3; Fig. 2 View FIGURES 2 C–D). The tadpole is described in Myers and Donnelly (1997), Noonan and Bonett (2003), and Señaris and Ayarzagüena (2005).

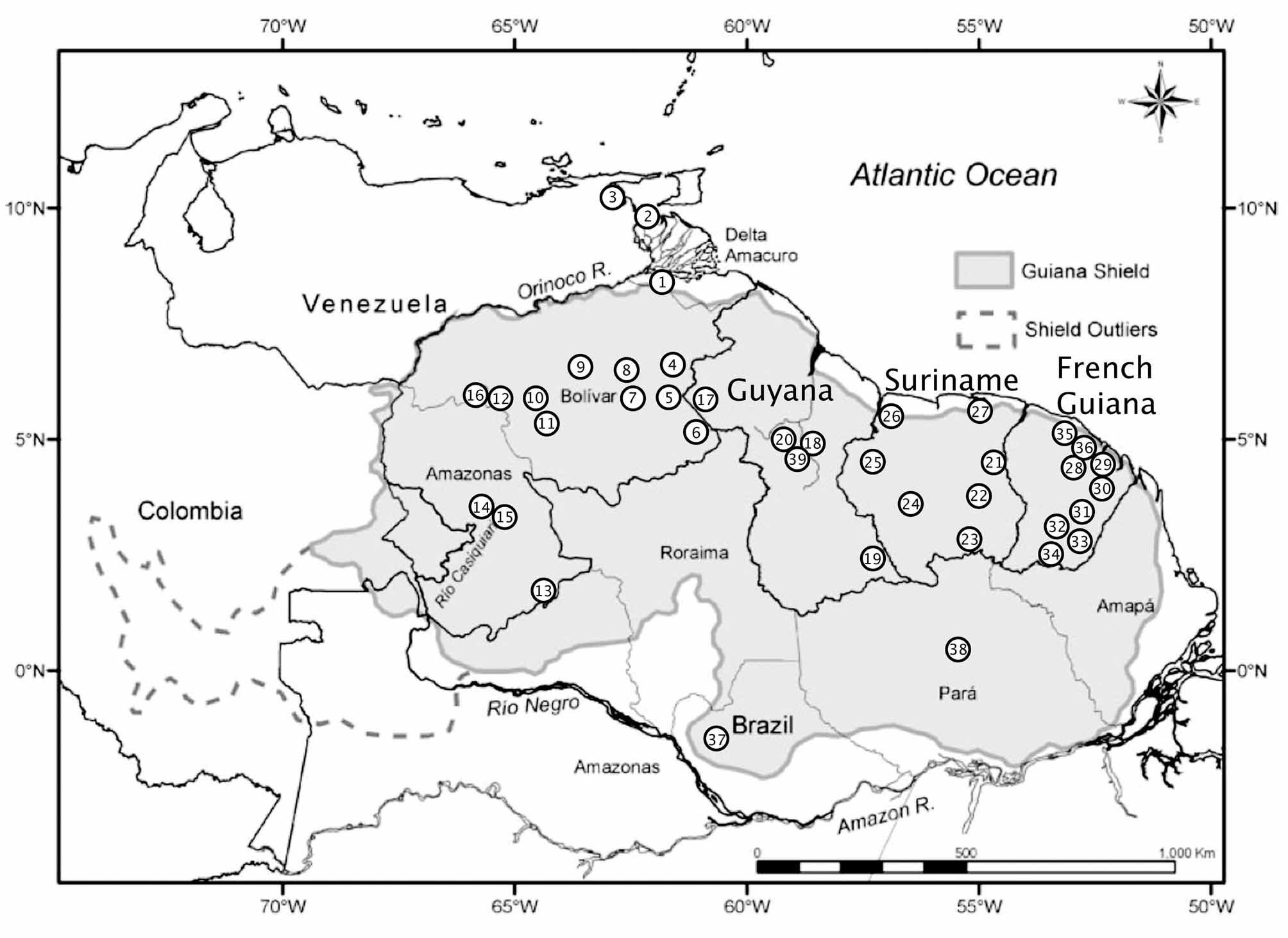

Ecology and distribution. This species is known to occur in the Guiana Shield and the Amazon rainforest. It has a broad distribution, from the summits of several western tepuys (table mountains) to the Gran Sabana and lowland forests (50–2000 m). It has always been found in the vicinity of clear water and often fast flowing streams, perching on vegetation. Specimens have been recorded for Brazil ( Rodrigues et al. 2010), French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela. It is very likely to appear in the Brazilian Guiana Shield (see Myers & Donnelly, 2001: 23).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Hyalinobatrachium cappellei

| Castroviejo-Fisher, Santiago, Vilà, Carles, Ayarzagüena, José, Blanc, Michel & Ernst, Raffael 2011 |

Hyalinobatrachium igniocolus Barrio-Amorós and Castroviejo-Fisher, 2008 : 235

| Barrio-Amoros 2008: 235 |

Hyalinobatrachium eccentricum

| Noonan 2003: 92 |

| Myers 2001: 16 |

Hyalinobatrachium crurifasciatum

| Lescure 2000: 78 |

| Myers 1997: 9 |

Cetrolenella taylori

| Lescure 1975: 390 |

Centrolenella fleischmanni

| Goin 1964: 1 |

Hylella cappellei

| Jeude 1904: 94 |