Callimico goeldii (Thomas, 1904)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5730714 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5730816 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DF668780-FFDC-FFCF-FF32-F760687DE6A6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Callimico goeldii |

| status |

|

17 View On .

Goeldi’s Monkey

French: Callimico / German: Springtamarin / Spanish: Titi de Goeldi Other common names: Callimico, Goeldi's Marmoset, Goeldi’'s Tamarin

Taxonomy. Midas goeldii Thomas, 1904 ,

Acre, Rio Yaco, Brazil .

Currently monotypic, but the genetic structure of the founder stock of captive individuals indicates that more than one cryptic subspecies or species may be represented.

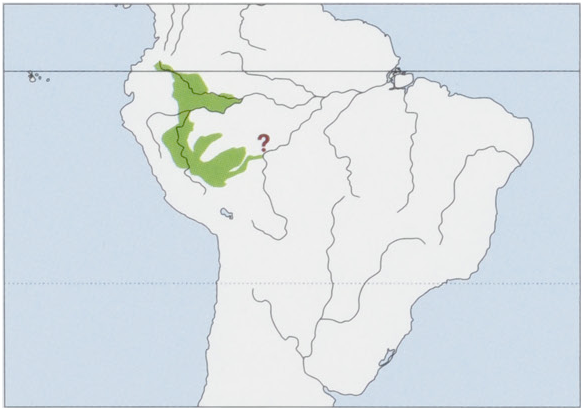

Distribution. Upper Amazon in S Colombia, W Brazil, E Peru, and N Bolivia, from the Rio Caqueta in Colombia, S through the Peruvian Amazon and the extreme W Brazilian Amazon into the Pando region of Bolivia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 19-25 cm, tail 26-35 cm; weight 366 g (males, n = 3) and 355 g (females, n = 5). Weights are higher in captivity: 450-600 g. Goeldi’s Monkey is identified by its long, disheveled, coal-black fur, which is broken only by a few buffcolored marks on the nape and, in some individuals, similarly hued rings at the base of the slightly bushy tail. There is a heavy cape over the head and shoulders. The head is rounded, jaws are somewhat protruded, and the nose is notably pug-like. Skin oflips, snout, rims of ears, hands, and feet is black.

Habitat. Goeldi’s Monkey travels and forages low in the forest and prefers dense undergrowth. It uses mostly primary (mature) forest with a dense understory, but also secondary forest and, importantly, bamboo forest and stream edge where fungi are more abundant. They are found only where bamboo forest is present, and their highest densities (4-5 groups/km®) are in north-eastern Bolivia where bamboo forestis abundant. Seasonal change in habitat use has been recorded in north-western Bolivia. In the dry season, they tend to use forest with Heliconia (Heliconiaceae) dominating the understory and bamboo thickets, probably tracking abundance of small prey and searching for fungi. Goeldi’s Monkey is an understory specialist and is seen at heights of 4-5 m above the forest floor. It rarely goes up to the forest canopy and never to the upper canopy. Ofthe callitrichids,it is the strongest leaper and has the most evident anatomical adaptations for vertical clinging and leaping between small trees,large tree trunks, and lianas at these low heights (long hindlimbs and modifications of the ankle and shoulders for leaping, dissipating compressive forces, and holding onto vertical supports).

Food and Feeding. Goeldi’s Monkeys eat fruit, gum, fungi, and small animals. Annually, fruit comprises ¢.29% of the diet, less than the sympatric tamarins (saddle-back tamarins 49% and Red-bellied Tamarins, Saguinus labiatus , 58%). This disparity is because of Goeldi’s Monkey's propensity to eat fungi, not just as a fallback food when fruit is scarce but also throughout the year. Fruit contributes more than 20% of the diet in the wet season in September—April, more than 40% in January-March, more than 70% in February, but only 3% in May. Goeldi’s Monkey eats fruits from more than 50 species, but it relies on relatively few species in certain months. At one site in north-western Bolivia, Inga thibaudiana ( Fabaceae ) was a key resource at the end of the wet season (January-February), Leonia glycycarpa ( Violaceae ) in March, Celtis iguanaea ( Ulmaceae ) in the early dry season (April-May), Cecropia sciadophylla ( Urticaceae ) in the peak of the dry season (August-September), Pourouma (Urticaceae) in October and December, and Micropholis (Sapotaceae) in November, the early wet to middle season. Gums are eaten sporadically, including the spontaneous exudation from bean pods of Parkia pendula ( Fabaceae ). Fungi are a staple and include the fruiting bodies of five species: three basidiomycete jelly ear fungi, Auricularia auricula, A. delicata, and A. cornea ( Auriculariaceae ) found on rotting wood (fallen tree trucks and branches), and two species of ascomycete bamboo fungi, Ascopolyporus polyporoides and A. polychrous ( Clavicipitaceae ), which produce thin, rubbery sporocarps with a tough outer layer and a clear gelatinous interior on the culms of Guadua weberbauer: (a dominant species in forests of northern Bolivia). Fungi are eaten throughout the year but are especially important in the dry season when they contribute ¢.40% of the diet (63% has been recorded for July). Goeldi’s Monkey is more insectivorous than the tamarins with which it associates. Eating insects and other small arthropods (excluding foraging for them) comprises 20% or more ofits feeding time in eight months of the year—with a high in December at b1%—and neverless than 10%. Orthopterans (generally large; 2:5-6 cm in length) are predominant, comprising 41% ofthe insect diet. Smaller numbers ofstick insects, scorpions, spiders, cicadas, mantids, cockroaches, and moths are also eaten. Groups of Goeldi’s Monkey forage in the understory on thin branches and in the leaf litter on the ground, using pounce and capture techniques in open substrates, similar to the mustached tamarins that travel and forage above them. It does not search in holes and crevices—sites favored by saddle-back tamarins. Small lizards, frogs, toads, and bird eggs are also eaten, and being close to the ground, Goeldi’s Monkey finds more of these prey than do either of the sympatric tamarins higher up in the forest.

Breeding. Singleton births to a single breeding female in each group are typical. Physiological reproductive suppression of subordinate females typical of marmosets and tamarins is absent in Goeldi’s Monkey. In the wild,it is possible that about one-third of groups have two breeding females. There can be more than one adult male in a group, indicating that the mating system may be monogamous or polyandrous, and polygyny is a possibility in groups with two breeding females. It is unknown if the two breeding females are mother and daughter, or if there is a reduced survival rate of infants in these cases. Female Goeldi’s Monkeys breed twice a year, having postpartum ovarian cycles allowing for pregnancy shortly after giving birth. Copulation has been recorded about three weeks after the female has given birth, and males may show mate guarding, traveling close to the female at this time. Births in one group occurred in February—-March (second half of the wet season) and late August (end of the dry season). The interbirth interval is about six months. The average ovarian cycle lasts ¢.24 days. In captivity, gestation lasts 151-152 days. Fully furred newborns (45-66 g) are about 10% of their mother’s weight. In the wild, weaning begins at 3-5 months, but nursing continues for about five months. The mother carries her infant exclusively for the first 3—4 weeks, but subsequently all group members carry and eventually (seen when the infant was as young as 26 days old) share food with it. In the first month, the infant is carried continuously, but in the second month, it is carried for c.60-65% of the time, occasionally being forced off the back ofits carrier. At 2-5 months, the infant leaves the carrier for brief excursions on its own. Group members provide food items to the infants. Juveniles (seven months) sometimes try to carry an infant, but they have insufficient strength. Juveniles pass through a stage of robbing food until they are skilled in finding and catching it themselves. In captive groups, sexual maturity is reached at ¢.57 weeks (48 weeks for one individual in the study), similar to lion tamarins ( Leontopithecus ) but earlier than other callitrichids (16-21 months). Infant and juvenile Goeldi’s Monkeys grow faster than other callitrichids, perhaps because the mother is suckling only one infant at a time.

Activity patterns. Goeldi’s Monkey groups leave their sleeping sites at 06:15-07:30 h, and end their day at ¢.17:00 h, sometimes as late as 18:00 h, resting and scanning until entering a sleeping site around sunset. Sleeping sites are typically vine tangles and dense vegetation at 10 m or higher above the forest floor. Their overall activity budget, recorded in a long-term study in north-western Bolivia, was: resting 66%, traveling 17%, feeding 9%, foraging 6%, and other behaviors 2%. Goeldi’s Monkey scans more when resting (87%) compared with saddle-back tamarins (71%) that tend to use canopy levels a little above them and Red-bellied Tamarins (66%) that occur even higher in the forest.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Goeldi’s Monkeys live in small groups (4-5 ind/group; range 2-12) and have home ranges larger than 100 ha. Three groups studied in the Pando region over ten years had home ranges of 150 ha, 114 ha, and more than 80 ha. The largest of these home ranges covered those of five mixed-species groups of Red-bellied Tamarin and Weddell’s Saddle-back Tamarin (S. weddelli ) (with home ranges of ¢.30 ha), with which the group of Goeldi’'s Monkeys associated regularly. The home range of a group studied in an 820-ha forest at Fazenda Experimental Catuaba near Rio Branco in Acre State, Brazil, was 59 ha. Home-range overlap with other Goeldi’s Monkey groupsis small (e.g. only 3% in the 59-ha home range) and encounters between groups are rare compared with tamarins. Unlike tamarins, groups of Goeldi’s Monkeys spend no more time in the periphery of their range than elsewhere, and they do not appear to defend home ranges or food sources. Daily home ranges are 2-20 ha. Groups of Goeldi’s Monkey, studied to date, form mixed-species groups with Red-bellied Tamarin and Spix’s Saddle-back Tamarin (S. fuscicollis ). One study in the Pando region found that they are near to or at least in vocal contact with mixedspecies groups of tamarins ¢.53% of the time; a second study in Acre, estimated 61% of the time. At the Pando site, the home range of 150 ha meant that Goeldi’s Monkeys associated with numerous tamarin groups; joining up and separating as they entered and left the tamarins’ home ranges. Goeldi’s Monkeys travel with tamarins more in the wet season (88%) when all species are eating more fruits and dietary overlap is highest. In the dry season, their association is reduced to ¢.37% of Goeldi’s Monkey time (as low as 13% in some months), and dietary overlap is much reduced; Goeldi’s Monkeys eat more fungi, whereas tamarins eat more nectar and gum. Goeldi’s Monkeys use more stream edge and bamboo clumps when looking for fungi in the dry season. In the wet season, they eat more fruits and tend to move slightly higher in the forest to do so. In association with tamarins, Goeldi’s Monkeys also tend to travel and forage slightly higher above the ground. Advantages to Goeldi’s Monkey of traveling in association could accrue from them using the knowledge of tamarins in finding fruiting trees and also in the safety in numbers when they are required to move up in the forest to reach the fruits. When Goeldi’s Monkeys arrive at a tall tree in fruit before the tamarins, they tend to wait in the understory until the tamarins arrive. Nevertheless, Goeldi’s Monkeys eat fruits of certain very tall trees only when they fall to the forest floor. Goeldi’s Monkeys, with small groups and large home ranges, occur at low densities of ¢.4-5 ind/km?, in contrast to densities of tamarins that can reach 50 ind/km?. Densities of Goeldi’s Monkeys have been found to be slightly higher and group sizes larger at a long-term study site near the city of Rio Branco: 0-8-1-2 groups/km? and groups of 7-12 individuals.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. Goeldi’s Monkeys are vulnerable because of their low densities, very patchy distributions, and habitat loss. They are rare and elusive, their occurrence is patchy, and they use large home ranges. As a result of the low densities and secretive habits of Goeldi’s Monkeys, they can be missed during primate surveys, and their geographic distribution is poorly known. It is believed that this patchy distribution is related to sensitivity to seasonal resource availability, particularly distribution and abundance of fungi. Groups of Goeldi’s Monkey will abandon core areas of their range, either moving into a new area or simply disbanding. It is probable that they experience shortterm fluctuations in abundance and distribution of fungi and long-term changes associated with forest succession, particularly the bamboo clumps that provide their key resources. Goeldi’s Monkey has been recorded sporadically through a large area of the western Amazon, but it seems to be most common in the Pando Department of northern Bolivia. The Pando has a long history of human occupation, particularly connected with subsistence slash-and-burn agriculture, cultivation of hardwoods and fig trees, occupation by rubber-tappers (“seringueiros”) from the late 1800s, and collection of Brazil nuts (“castanheiros”) from the 1930s. In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a major primate export trade in the region, but the major threat today is logging, resulting in road construction, colonization, and cattle ranching—all causing widespread forest loss. Goeldi’s Monkeys occur in Serra do Divisor National Park and possibly the Rio Acre Ecological Station in Brazil. Presumably, the national natural parks of Amacayacu, Cahuinari, and La Paya in Colombia; and Manu National Park and Biosphere Reserve in Peru.

Bibliography. Aquino & Encarnacion (1994b), Azevedo & Rehg (2003), Beck et al. (1982), Buchanan-Smith (1991¢), Buchanan-Smith et al. (2000), Calouro (1999), Carroll (1982), Carroll et al. (1990), Christen (1994, 1998, 1999), Christen & Geissmann (1994), Dalton & Buchanan-Smith (2005), Davis (1996, 2002), Defler (1994b, 2003b, 2004), Dettling (2002), Dettling & Pryce (1999), Dutrillau, Lombard et al. (1988), Encarnacion & Heymann (1998), Feistner & Price (1991), Ferrari, Iwanaga, Messias et al. (1999), Garber & Leigh (2001), Garber & Rehg (1998), Garber, Blomquist & Anzenberger (2005), Garber, Sallenave et al. (2009), Hanson, Hall et al. (2006), Hanson, Hodge & Porter (2003), Heltne, Turner & Wolhandler (1973), Heltne, Wojcik & Pook (1981), Hernadndez-Camacho & Barriga-Bonilla (1966), Hernandez-Camacho & Cooper (1976), Hershkovitz (1977), Hill (1959), Jurke (1996), Jurke, Pryce & Dobeli (1995), Jurke, Pryce, Hug-Hodel & Dobeli (1995), Lorenz (1971), Masataka (1982, 1983), Pastorini et al. (1998), Pook (1978), Pook & Pook (1979, 1981, 1982), Porter (2001a, 2001b, 2001¢, 2004, 2006, 2007), Porter & Christen (2002), Porter & Garber (2004, 2007, 2010), Porter et al. (2007), Power et al. (2003), Pryce et al. (2002), Rehg (2006a, 2006b, 2007, 2009, 2010), Ross et al. (2010), Rylands et al. (2009), Schradin & Anzenberger (2003), Schradin et al. (2003), Seuénez et al. (1989), Vasarhelyi (2002), Warneke (1992), Ziegler et al. (1989).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.