Glassella Campos & Wicksten, 1997

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5252/zoosystema2020v42a6 |

|

publication LSID |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C87A10FB-E817-4293-96FD-00C2EF82D371 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3703640 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/DE24878A-F651-D62F-30D7-C77B58DCFA71 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Glassella Campos & Wicksten, 1997 |

| status |

|

Genus Glassella Campos & Wicksten, 1997 View in CoL

Glassella Campos & Wicksten, 1997: 69 View in CoL .

TYPE SPECIES. — Glassella costaricana (Wicksten, 1982) [ Pinnixa ] assigned by monotypy when genus was erected ( Campos & Wicksten 1997).

ORIGINAL DESCRIPTION BY CAMPOS & WICKSTEN (1997). — “Carapace suboblong, dorsal surface pockmarked, wider than long, integument firm, regions not defined; cardiac ridge lacking; front truncated, with shallow median sulcus. MXP3 [= third maxilliped] with ischium-merus pyriform, fused, separated by faint line and distal margin truncated; palp as long as ischium-merus, 3-segmented, dactylus small, digitiform, inserted sub-distally on inner face of conical propodus; carpus stout, longer than combined length of propodus and dactylus; exopod with median lobe on outer margin, flagellum 2-segmented. WLl-4 [= walking leg] pockmarked, relative length 3> 2> 1> 4, WL3 considerably the longest. Abdomen of female with 6 somites and telson free, widest at third somite; tapering from fourth somite to triangular telson. Male unknown.”

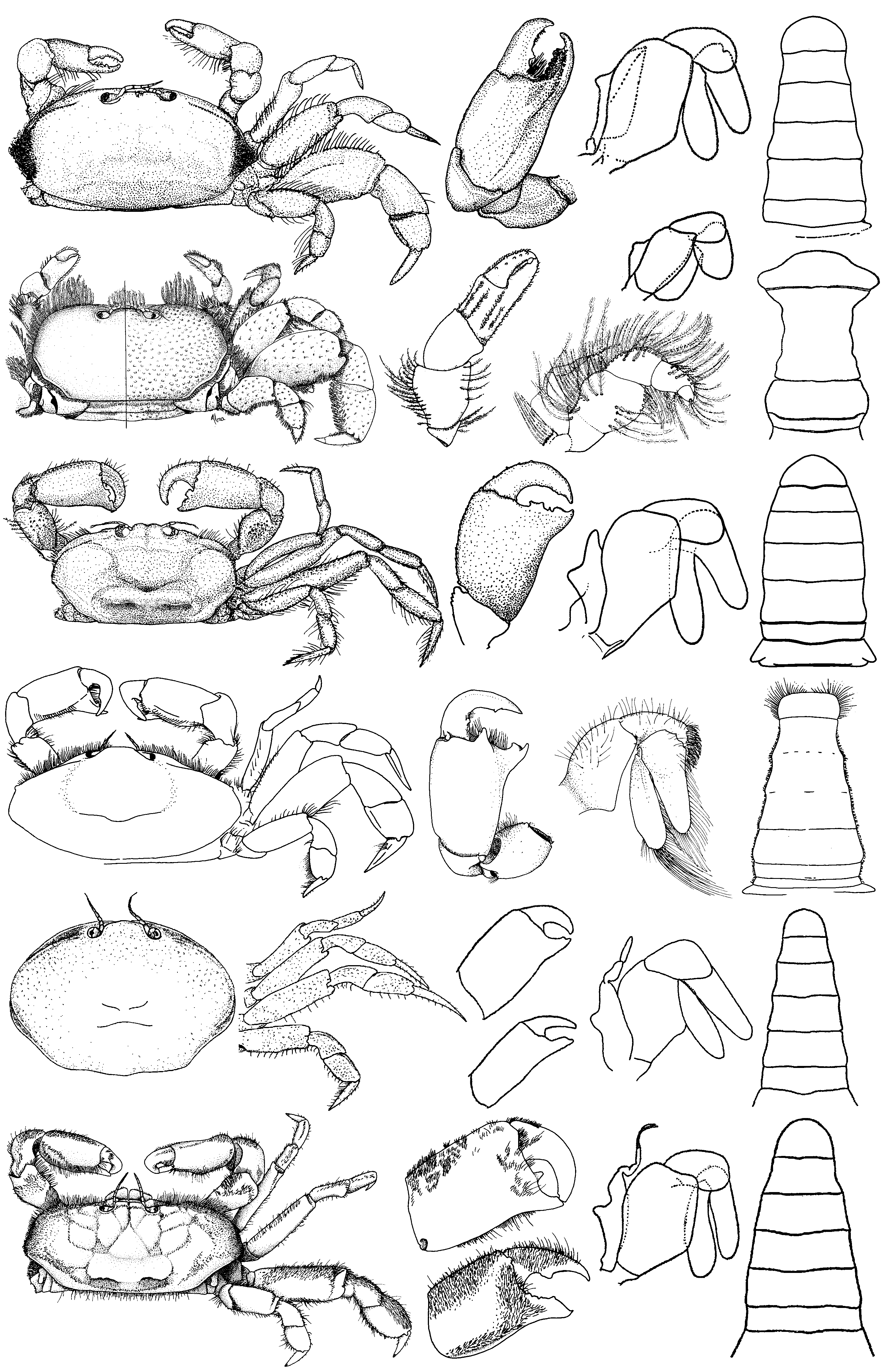

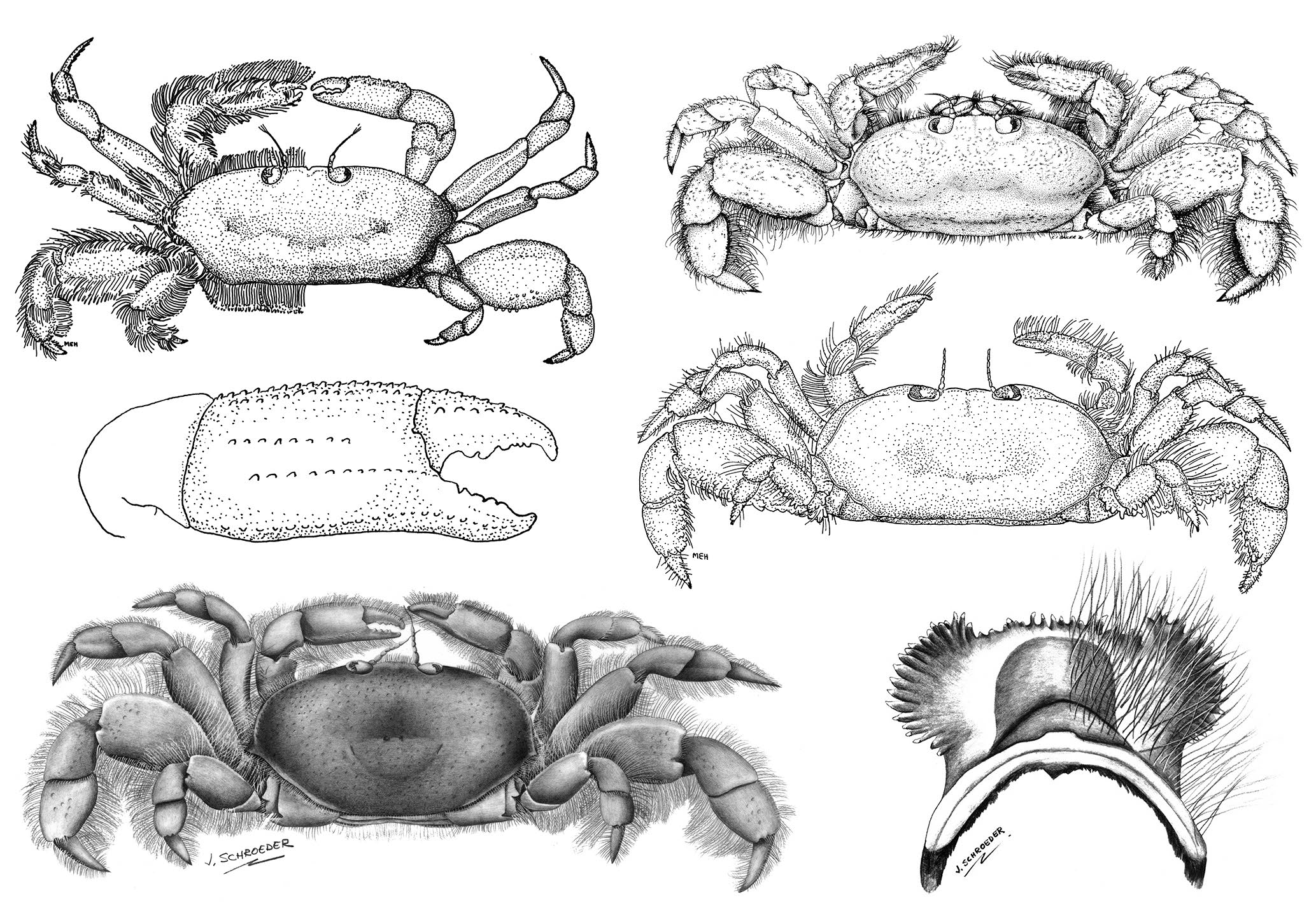

DIAGNOSIS. — (Modified from Campos & Wicksten 1997). Carapace transversely oblong, wider than long, dorsal surface smooth, punctate, integument firm, regions poorly defined, sometimes with blunt ridge across posterior portion of carapace, ridge not extending entirely across carapace. Third maxilliped with ischiomerus pyriform or subtrapezoidal, fused, sometimes separated by faint line; palp as long as or longer than ischiomerus, three-segmented; dactylus sometimes ( Glassella costaricana ) very small, inserting sub-distally on inner face of conical propodus, typically large, nearly as long as ischiomerus, inserting near base of propodus. Chelipeds small, subcylindrical to weakly compressed, setose; palm typically with one or more longitudinal ridges or lines of tubercles or setae on outer surface; fingers slender, dactylus superior margin typically with row of long setae. Walking pereopod articles heavy, stout, often marginally tuberculate or dentate, relative lengths P4> P3 ≥ P2> P5. Male pleon terminally broad, lobate to weakly polygonal; third pleonal somite typically bearing gonopodal plate or sheath extending between or against gonopods ( Fig. 2 View FIG E-I). Male gonopods heavy, stout, terminally forming sharp angle, spinose tip, or distally to laterally directed corneous filament.

INCLUDED SPECIES. — Glassella abbotti ( Glassell, 1935) n. comb. [ Pinnixa ];

Glassella arenicola (Rathbun, 1922) n. comb. [ Pinnixa ];

Glassella faxoni ( Rathbun, 1918) View in CoL n. comb. [ Laminapinnixa View in CoL ]; Glassella floridana (Rathtbun, 1918) View in CoL n. comb. [ Pinnixa View in CoL ];

Glassella miamiensis ( McDermott, 2014) View in CoL n. comb. [ Laminapinnixa View in CoL ]; Glassella leptosynaptae (Wass, 1968) View in CoL n. comb. [ Pinnixa View in CoL ];

Glassella vanderhorsti (Rathbun, 1922) View in CoL n. comb. [ Laminapinnixa View in CoL ].

MATERIAL EXAMINED. — In addition to the material included in the phylogenetic analyses ( Table 1 View TABLE ) the following samples were available for examination:

Glassella abbotti n. comb. — ULLZ 5619 (26), ULLZ 7392 (Bahía de los Ángeles, Mexico) ;

Glassella arenicola n. comb. — NCBN-ZMA De242240 ( holotype, Spanish Harbor, Curaçao), ULLZ 6070 ( Aruba) ; ULLZ 8989 ( Puerto Rico), ULLZ 9248 (Ft. Pierce, FL, USA) ;

Glassella costaricana . — UF 18960 ( Isla Culebra, Panama); Glassella faxoni n. comb. — ULLZ 14837 ( Campeche, Mexico), ULLZ 14030 ( Isla Margarita , Venezuela), ULLZ 14098 (2) (Punta Elvira, Venezuela) ;

Glassella floridana n. comb. — ULLZ 5649 , ULLZ 17733 (Fort Pierce, FL, USA) , ULLZ 13888 (Content Keys, FL, USA) , ULLZ 14903 (2) (Alligator Point, FL, USA) , ULLZ 13096 , ULLZ 14038 (4), ULLZ 14181 , ULLZ 15010 (St. Joseph’s Bay, FL, USA) , ULLZ 17469 (northeastern Gulf of Mexico) ;

Glassella miamiensis n. comb. — ULLZ 5724 , MNHN-IU-2017-9364 = former ULLZ 7398 (2), ULLZ 11709 , ULLZ 13338 , ULLZ 14003 , ULLZ 14011 , ULLZ 14138 (Fort Pierce, FL, USA); Glassella leptosynaptae n. comb. — ULLZ 14834 ( Florida Bay, FL, USA) ;

Glassella vanderhorsti n. comb. — NCBN-ZMA.C RUS.D 242234 ( holotype, Spanish Harbor, Curaçao) .

REMARKS

The morphological similarities among species transferred to this genus have in most cases been noted previously ( Rathbun 1918, 1924; Glassell 1935a; McDermott 2014), although their resemblance to Glassella of Campos & Wicksten (1997) has likely remained unnoticed because of the weight given to differences in the third maxilliped ( Fig. 2G, H View FIG ), often an important character in pinnotherids. However, there are other cases among pinnotherid genera for which striking variation in the third maxilliped has been observed among closely related species. In Calyptraeotheres Campos, 1990 some species lack a third maxilliped dactylus, whereas in others it is present (Hernández-Ávila & Campos 2006).

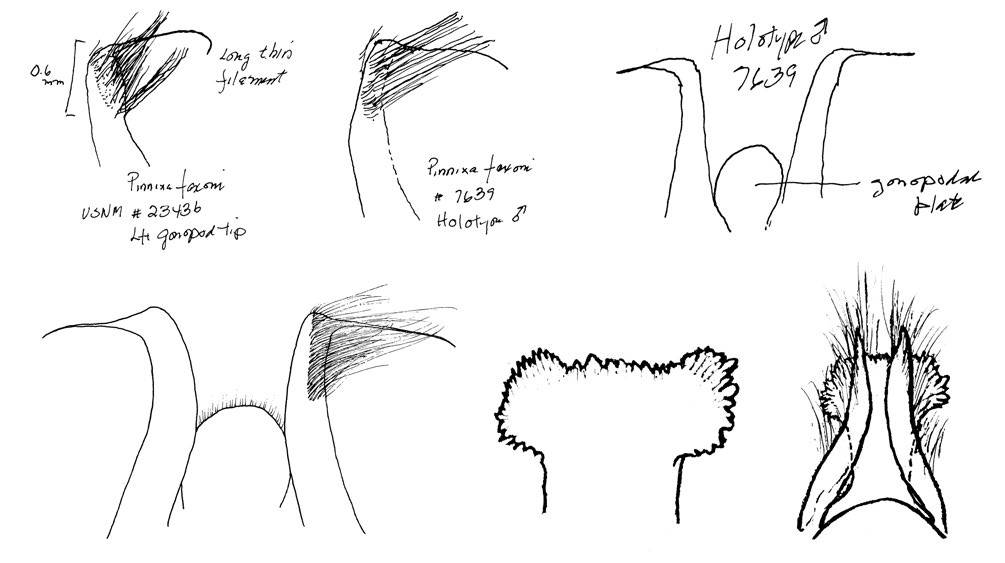

The genus Laminapinnixa was erected by McDermott (2014) to accomodate L. miamiensis , a newly described species for populations that we and colleagues had long regarded on morphological evidence as closely related to Glassella faxoni n. comb. and G. vanderhorsti n. comb. The genus was diagnosed in part by the presence in males of a plate (therein termed “abdominal plate” = our gonopodal plate) derived from the pleon (posterior to the gonopods), which in the description and discussion by McDermott (2014) are portrayed as a structure that must be “lifted” to expose the gonopods during copulation. However, this structure is in all unmanipulated examples of G. miamiensis n. comb. that we have examined positioned to extend from its more posterior origin obliquely between the gonopods (derived from the first pleonal somite) and then anterior to them, where it usually broadens terminally and separates the gonopods from the sternum when the pleon is flexed (as shown clearly by McDermott, 2014: fig. 7B). This would appear to not necessarily separate them from exposure for copulation when the pleon is extended (or, as they appear when illustrated with the pleon removed, Fig. 5F View FIG ). The broadened terminus of the plate in at least one related species can also perhaps move from anterior or posterior of the gonopods, provided the gonopods are flexed laterally, though this seems unlikely in G. miamiensis n. comb.

In the course of describing and investigating potential relationships of G. miamiensis n. comb. and seeking evidence of other species having this gonopodal plate, McDermott (2014) noted the unfortunate loss of types for potentially related species to which he had wished to make comparisons. By way of further explanation, most of these were among 98 pinnotherid specimens permanently lost to science when destroyed by the U.S. Postal Service, owing to the mishandling of a loan return shipment by a borrower in 2006. While this loss has also limited our own comparative efforts, one of us (DLF) and his late colleague Robert H. Gore had independently examined types and other now lost materials decades ago, at the time making rough-sketches of selected structures, several of which are herewith directly reproduced given the void they fill ( Fig. 4 View FIG ). In addition, high-quality, previously unpublished illustrations by several Smithsonian Institution illustrators, contracted by Robert Gore or the late Waldo Schmitt (the latter for a never-published manuscript by W. L. Schmitt and E. S. Davidson), are in some cases annotated so as to be clearly identifiable with the now-lost types or other materials on which they were based ( Fig. 5 View FIG ).

From this evidence, it is clear that both G. faxoni n. comb. and G. vanderhorsti have forms of the gonopodal plate in mature males that we regard to be homologs of that in G. miamiensis , in addition to their sharing a number of other characters that group them with G. miamiensis and its herewith assigned congeners. The illustrated male gonopodal plate for Glassella vanderhorsti , published by McDermott (2014) but reproduced here from the original figures with credit and voucher indicated ( Fig. 5F View FIG ), was in fact based on the Zoological Museum Amsterdam (now Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Netherlands) holotype male (NCBN-ZMA.C RUS.D 242234). In a very similar but smaller topotypic male specimen (USNM 56903), also collected by van der Horst but now among the lost materials, the gonopodal plate was found to be somewhat longer but terminally very similar to the holotype male and like that of G. miamiensis in that its terminal reaches were positioned anterior to the gonopods ( Fig. 4E, F View FIG ). Only in G. faxoni n. comb. was the male gonopodal plate found to be small enough to be positioned largely between the gonopods or to freely move its arched terminal lobe from anterior to posterior of the gonopods ( Fig. 4C, D View FIG ). As evident, the cataloged specimens upon which our figures, sketches, and notes are based were the same as examined by Rathbun (1918, 1924). This confirms personal communications of E. S. Davidson regarding gonopodal plates in these species, as were mentioned by McDermott (2014), who found the lack of Rathbun mentioning these plates in descriptions of G. faxoni n. comb. and G. vanderhorsti as reason to question their congeneric assignment with G. miamiensis . We suspect that Rathbun at the time attached little importance to gonopods as characters, especially among pinnotherids in the early years while she was working primarily with a hand-lens.

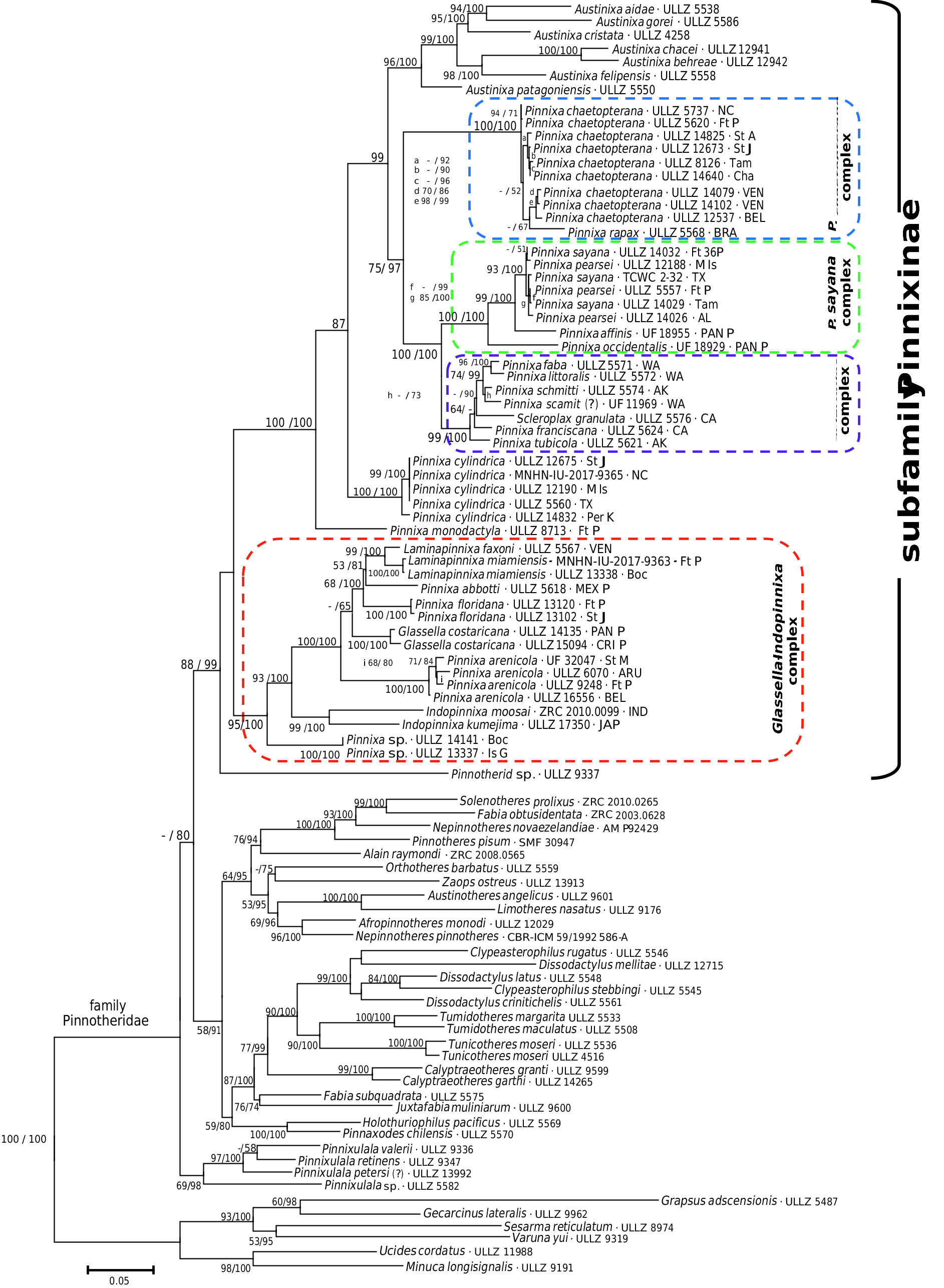

While the male gonopodal plate, or some ramification of it, may prove to unite most if not all species that we here assign to Glassella , our molecular phylogeny includes species in which it is at very least not reported to date, or for which intact male specimens are lacking. This remains the case for the generic type species, G. costaricana , known only from a female at the time of description. Our phylogenetic analyses included two additional females, but we also attempted inclusion of tissues from a very small mutilated male specimen (UF 18960) that appeared to be this species. Its identity as G. costaricana was confirmed by clear match of its 16S mitochondrial sequence to those of the females, but it was not included in the final phylogenetic analysis for lack of additional sequence data. Unfortunately, damage to its pleon and sternum obliterated evidence that might have made obvious the presence or absence of a gonopodal plate, leaving that question unresolved. We strongly suspect that the “enclosing sheath” of the gonopod in G. arenicola , as reported but only partially illustrated by Thoma et al. (2009), could represent yet another variation in this structure, and this species clearly groups with those that have the more obviously developed gonopodal plate. Glassella miamiensis and G. faxoni share the plate and are closely related both morphologically and genetically ( Fig. 1 View FIG ), but we cannot yet determine if G. leptosynaptae and G. vanderhorsti (at least the latter of which also has the plate) are included in that same well-supported molecular genetic clade for present lack of sequence quality material.

Thorough study of the first pleonal somite in mature males for all other suspected members and close relatives of Glassella is required to determine if any homologous ramification of the gonopodal plate may have also in those been thus far overlooked. This is to be undertaken in the course of coming descriptions of the American species “ Pinnixa sp. (ULLZ 13337 and ULLZ 14141)” from Panama ( Fig. 1 View FIG ) and at least three additional new western Atlantic species that clearly represent Glassella in morphology, but for which we at present lack sequence quality materials. Further studies must also include molecular and morphological examinations of potentially related species, especially the eastern Pacific American species Pinnixa bahamondei Garth, 1957 , P. darwini, Garth, 1960 , P. hendrickxi Salgado-Barragán, 2015 , P. pembertoni Glassell, 1935 , and perhaps P.transversalis (H. Milne Edwards & Lucas, 1844) . From our preliminary morphological observations of materials used in the present molecular study, we can state that a clear ramification of the male gonopodal plate is present in the eastern Pacific species G. abbotti , underpinning our inclusion of it in Glassella on the basis of more than solely molecular phylogenetics.

Further studies are also required to more thoroughly compare the Indo-West Pacific genus Indopinnixa to the American Glassella . We retain separation of these genera as sister clades, though only two of the seven species assigned to Indopinnixa could for the present be represented in the molecular genetic analysis. Furthermore, only one of these two species was represented by an intact male specimen, the other represented only by a donated tissues sample. The intact male of I. kumejima was stained and carefully examined, and no evidence of a gonopodal plate or ramification thereof could be found, suggesting this could be a character of use in separating at least some species of the two genera.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

InfraOrder |

Brachyura |

|

Family |

Glassella Campos & Wicksten, 1997

| Theil, Emma Palacios & Felder, Darryl L. 2020 |

Glassella

| CAMPOS E. & WICKSTEN M. K. 1997: 69 |