Gerrhosaurus Wiegmann, 1828

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3750.5.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DC8E9834-EBFE-41EC-91D1-69EE0ED2DDF5 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5659898 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CC6587F7-0811-FFF1-9BC0-DE629F5DFE90 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Gerrhosaurus Wiegmann, 1828 |

| status |

|

Pleurotuchus Smith, 1837 Angolosaurus FitzSimons, 1953

Type species: Gerrhosaurus flavigularis Wiegmann, 1828

Content: Gerrhosaurus flavigularis Wiegmann, 1828 ; Gerrhosaurus typicus (Smith, 1837) ; Gerrhosaurus nigrolineatus Hallowell, 1857 ; Gerrhosaurus multilineatus Bocage, 1866 a; Gerrhosaurus auritus Boettger, 1887 ; Gerrhosaurus intermedius Lönnberg, 1907 comb. nov.; Gerrhosaurus skoogi Andersson, 1916 ; Gerrhosaurus bulsi Laurent, 1954 .

Diagnosis: The monophyly of Gerrhosaurus is established on the basis of a suite of nuclear and mitochondrial genetic characters (see above). These moderate-sized lizards are fairly well armoured and the head and body may be cylindrical, cyclotetragonal or slightly depressed; differentiated from the genera Broadleysaurus and Matobosaurus by its smaller size (maximum SVL 213 mm compared to 245 mm and 285 mm respectively for the latter two genera) and less robust appearance; most species of Gerrhosaurus have only eight ventral scale rows longitudinally (but 10 in G. typicus ), whereas Broadleysaurus has 9–10 and Matobosaurus has 12–20; it also differs from Broadleysaurus by having 49–67 versus 31–38 transverse dorsal scale rows (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943, 1953; De Witte 1953; Laurent 1954, 1964; Broadley 1966; De Waal 1978; Jacobsen 1989).

Description: Head large, moderate or small, its length included in SVL 3.3–4.8 times (young lizards) to 4.0– 8.4 times (adults); head shields smooth or weakly striated; rostral in contact with, or separated from, the frontonasal; prefrontals well separated, slightly separated, in narrow contact, or in broad contact; supraoculars 4; supraciliaries 4–5 (rarely 3 or 6); tympanic shield narrow and band-like to broad and crescentic; body cyclotetragonal, slightly depressed in some G. t y pi cu s, or almost cylindrical ( G. skoogi ); dorsal scales weakly to strongly keeled, smooth or striated, in 20–28 (32–35 in G. skoogi ) longitudinal and 49–67 transverse rows (usually counted from row posterior to nuchals to row above vent); lateral scales keeled, striated or smooth; ventral plates in 8 or 10 ( G. typicus only) longitudinal and 30–42 transverse rows (counted “from pectoral to anal shields” according to Loveridge 1942; i.e. from axilla to row before enlarged ventral plate); femoral pores 9–27 per thigh; fourth toe with 14–22 subdigital lamellae; largest known specimens: unknown sex 613 mm (213 mm SVL + 400 mm tail length), male 485 mm (163 + 322), but another male had a SVL of 175 mm female: 475 (142 + 333), but another female had a SVL of 157 mm; tail 1.0 to 2.5 times SVL (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943, 1953; De Witte 1953; Laurent 1954, 1964; Broadley 1966; De Waal 1978; Jacobsen 1989).

Distribution: Widespread in Africa south of the equator, extending northwestwards into Gabon and Cabinda, and north-eastwards through Uganda and Kenya to southern Sudan and Ethiopia (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943; De Witte 1953; Mertens 1955; Broadley 1966, 1971; De Waal 1978; Auerbach 1987; Jacobsen 1989; Lang 1991; Branch 1998; Spawls et al. 2002; Adolphs 2006, 2013; Bates et al. in press.).

Note: Lizards in this genus are commonly known as ‘plated lizards’.

Status of ‘ Gerrhosaurus major ’

The type locality of G. major ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ) is Zanzibar, an island off the coast of Tanzania, but G. m. major has an extensive range in the eastern half of Africa, from northern KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa to Ethiopia; G. m. bottegoi was described from Valley of Ghinda in Eritrea and has a fragmented distribution, extending from northeast Africa (where it occurs together with the nominate subspecies in Kenya) across the continent to West Africa (Duméril 1851; Del Prato 1895; Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943; Broadley 1966; Jacobsen 1989; Branch 1998; Spawls et al. 2002; Adolphs 2006, 2013; Bates et al. in press.). The two subspecies are distinguishable only by their colour patterns (Broadley 1987). Our analysis included samples from southern and eastern Africa identifiable as G. m. major and one sample from Atakpame in Togo referable to G. m. bottegoi ( Table 1). The Togo sample is embedded within samples of G. m. major . Based on our molecular data, plus the weak morphological differences (i.e. colour variation) used for recognition of the two subspecies, we relegate G. bottegoi Del Prato, 1895 to the synonomy of Broadleysaurus major (Duméril, 1851) comb. nov.

Status of ‘ Gerrhosaurus validus ’

The two currently recognized subspecies of G. va l i d us each form separate monophyletic clades. In addition, sequence divergences between these taxa are much larger than would be expected for subspecies and instead are at the level of species (i.e. 8.5% ND2, 4.1% 16S). The two taxa are morphologically well differentiated (e.g. subocular excluded from lip by a labial in validus , in contact with lip in maltzahni ; longitudinal rows of dorsals 28– 34 in validus , 25–30 in maltzahni ; longitudinal rows of ventrals 14–20 in validus , 12–14 in maltzahni ; Loveridge 1942, FitzSimons 1943) and occur allopatrically. Gerrhosaurus v. validus occurs from Limpopo Province in South Africa northwards to Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi, while G. v. maltzhani (type locality: Farm Roidina, north of Omaruru, Namibia; De Grys 1938) is restricted to northern Namibia and southern Angola (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943; Broadley 1966; Visser 1984a; Jacobsen 1989; Branch 1998; Spawls et al. 2002; Adolphs 2006, 2013; Bates et al. in press.). The two taxa appear to be separated by the Kalahari Desert (Visser 1984a). Our samples of G. v. validus were from Limpopo Province in South Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe; G. v. maltzahni was sampled in both Namibia and Angola ( Table 1). The type locality for G. validus of “towards the sources of the Garrep [Gariep], or Orange River” (Smith 1849, Appendix, p. 9), i.e. in Lesotho, must be in error―as noted by FitzSimons (1943)―as the species is not known to occur anywhere south of 28o latitude (Branch 1998; Bates et al. in press.). The combination of molecular, morphological and geographical evidence suggests that the two taxa represent separate evolutionary lineages, and we therefore revive G. maltzahni De Grys, 1938 as a full species, as Matobosaurus maltzahni ( De Grys, 1938) comb. nov. The two species in the genus are illustrated in Figs 5 View FIGURE 5 & 6 View FIGURE 6 .

Status of taxa in the Gerrhosaurus nigrolineatus species complex

The type locality of G. nigrolineatus is “ Gaboon country, West Africa” (= Gabon; Hallowell 1857). This species has now been collected at several localities in Gabon (Pauwels et al. 2006), confirming its occurrence there. As currently understood it has a large distribution range, from Gabon and the lower Congo eastwards through southern Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.) to Uganda and Kenya in the east, then southwards as far as northern Namibia, northern Botswana and north-eastern South Africa (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943; De Witte 1953; Broadley 1966, 1971; Auerbach 1987; Jacobsen 1989; Branch 1998; Spawls et al. 2002; Bates et al. in press.; Uetz 2013). Our samples were from Kouilou region, Republic of the Congo (west-Central Africa) adjacent to Gabon, and Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa (East and Southern Africa) ( Table 1).

Our analysis showed that G. nigrolineatus as currently conceived is not monophyletic, although topology tests could not reject a monophyletic G. nigrolineatus as presently defined. However, given the observed topology, the well-supported west-Central African clade of G. nigrolineatus is more closely related to G. auritus , rather than to G. nigrolineatus from East and Southern Africa, and the nodes defining these groups are well-supported. Given the node support, as well as other lines of evidence (see below), we suggest that there is reasonably strong support that G. nigrolineatus as currently defined is not monophyletic. Although the phylogeny of Lamb et al. (2003) also recovered a sister relationship between G. nigrolineatus and G. auritus , only a single G. nigrolineatus sample from Mozambique was included. Because our analysis includes greater geographic coverage than previous studies, we were able to evaluate the status of G. nigrolineatus . In addition to the lack of monophyly for G. nigrolineatus , the west-Central African clade differs from the East and Southern African clade by large p -distances (13.0% ND2, 6.9% 16S). One individual (HB057, Arusha, Tanzania; Fig. 1) was found less than 140 km to the south-east of the approximate type locality of Gerrhosaurus flavigularis intermedia Lönnberg, 1907 (i.e. “steppe near the Natron lakes, Kibonoto”, northern Tanzania; p. 7). Taxonomic implications are that the East/Southern African clade represents a separate species, for which the name Gerrhosaurus intermedius Lönnberg, 1907 comb. nov. is available.

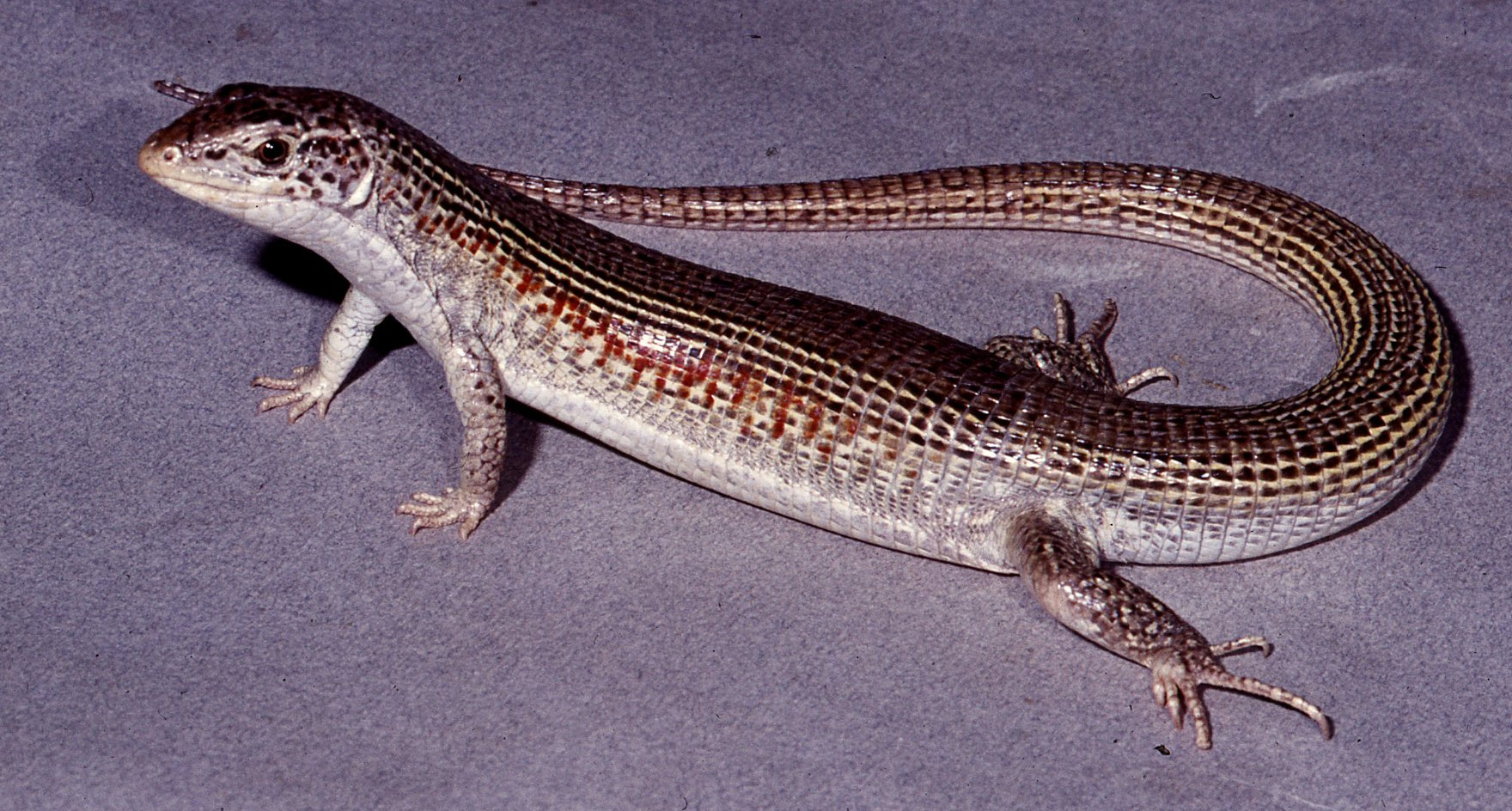

Loveridge (1942) relegated G. f. intermedia to the synonymy of G. n. nigrolineatus without explanation. Because of the similarity of taxa associated with the names G. flavigularis and G. nigrolineatus , the applicability of the name G. intermedius for eastern populations previously referred to G. nigrolineatus requires explanation. Although not mentioned in the text of Lönnberg’s (1907) description of G. f. intermedia , it is evident from his fig. 1b (left side of head) that there are four supraciliaries as in G. nigrolineatus (usually five in G. flavigularis ; Loveridge 1942, FitzSimons 1943). The proportions and scutellation of the head (fig. 1a) are also very similar to FitzSimons’ (1943) fig. 157 of G. nigrolineatus . In addition, Lönnberg’s description mentions that the flank scales of G. f. intermedia are strongly keeled, and minium red in colour with dark bars extending from the back. The prefrontals are shown to be in good contact, with a long median suture (indicated in Lönnberg’s fig. 1a). All of these features are rare or absent in G. flavigularis and often associated with G. nigrolineatus , including eastern populations that we now refer to G. intermedius ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 7 ).

In the Congo and Gabon voucher specimens ( G. nigrolineatus ) examined (Appendix I) there were four supraciliaries on either side of the head (e.g. PEM R20067, Fig. 8 View FIGURE 8 ) in all but one specimen (PEM R20066, Congo) which had five; flanks had weakly or moderately keeled scales in the two Congo specimens, weakly (5) or moderately (4) keeled in Gabon specimens; prefrontals in broad (PEM R20067) or moderate (PEM R20066) contact in Congo specimens, in broad (5) to moderate (4) contact in Gabon specimens. We refer all of the above specimens to G. nigrolineatus . The vouchered Mozambique sample of G. intermedius (TM 80959) from Moebase Village had four supraciliaries on either side of the head; flanks with strongly keeled scales; and prefrontals in broad contact.

Although Loveridge (1942: 511) was tempted to “separate an eastern race” of G. nigrolineatus , the only character he found useful was the number of longitudinal rows of dorsal scales, which numbered 24–28 in “West Africa” and 20–26 (but usually 22–24) in “East Africa”. Laurent (1954) later gave a count of 26 for a specimen from Dundo in north-eastern Angola that he assigned to G. nigrolineatus . For southern Africa these counts were given as 22–24 (usually 22) by FitzSimons (1943) and 20–24 (mostly 22–23) by Jacobsen (1989). The type description of G. nigrolineatus (Hallowell 1857) refers to 25 longitudinal rows of dorsals, while the holotype of G. flavigularis intermedia has 22 such rows (Lönnberg 1907). Laurent (1964) later referred a specimen from Mayombe (lower Congo) with 25 such rows to G. n. nigrolineatus , and four specimens from Pweto in Katanga, D.R.C., with 24–26 such rows to G. n. intermedius . The number of dorsal rows varied from 23 to 25 in both the Congo (N = 2) and Gabon (N = 9) specimens examined. The vouchered southern African sample of G. intermedius (TM 80959) had 24 longitudinal rows of ventrals. While there may be average differences in these counts between western and eastern populations, there is also some overlap, and the usefulness of this feature for separating G. nigrolineatus and G. intermedius requires further investigation.

According to Broadley (2007), G. nigrolineatus from Gabon and the lower Congo region has ragged dorsolateral stripes and smooth plantar scales, features which he felt may distinguish it from populations of this species elsewhere in Africa. The plantar scales of eastern populations of G. nigrolineatus (= G. intermedius ) are reportedly keeled (smooth and tubercular in G. flavigularis ) (FitzSimons 1943; Broadley 1966). In the Congo specimens examined, the back and flanks were olive to light brown with distinct cream, black-bordered, dorsolateral stripes, with a similarly coloured vertebral stripe that was continuous in one specimen (PEM R20066) and broken in the other (PEM R20067). Gabon specimens examined were light brown with scattered black and white lateral scales, and similar stripes, but the vertebral stripe was continuous in one specimen, broken in three and absent in five. As shown in Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 , MBUR 02993―a specimen sampled for the current analysis―also has typical dorsolateral stripes as described above, with a broken vertebral stripe. The original description of G. nigrolineatus refers to a yellow stripe on either side of the back, bordered internally (towards the centre of the back) by a black band; and also mentions that the centre of the back contains black spots in the form of longitudinal lines (Hallowell 1857). Colour photographs of the two syntypes of G. nigrolineatus indicated that both specimens have faded somewhat, but their colour patterns were not dissimilar to the Congo and Gabon material described above. ANSP 3729 had a pair of pale (cream) dorsolateral stripes with poorly defined black borders as well as a similar vertebral stripe anteriorly (not visible beyond the nape; Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 ), while ANSP 8825 (juvenile) was similar but lacked a discernible vertebral stripe ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 ).

Donald G. Broadley (in litt. 21 March 2013) noted that a specimen of G. nigrolineatus from Ponte Denis in Gabon in the collection of the Natural History Museum, Zimbabwe (Bulawayo) had smooth plantar scales, differing somewhat from the weakly keeled plantar scales of PEM R20067 (a detailed photographic image was used for comparison) from Republic of the Congo (Appendix I). In the Congo specimens examined, plantar scales were almost smooth or weakly keeled, while in the Gabon sample they were weakly (7) or very weakly (2) keeled. Based on photographs of one foot of each of the syntypes of G. nigrolineatus , the scales on the soles were weakly keeled. The plantar scales of the sampled specimen (TM 80959) of G. intermedius were strongly keeled, while those of 10 additional specimens from Mozambique were moderately keeled; two out of three specimens from Limpopo Province in South Africa had moderately keeled palmar scales, while one had distinctly keeled scales (Appendix I).

Although there was some variation in the extent and appearance of dorsal stripes and the keeling of plantar scales, the Congo and Gabon samples (including material referred to by Broadley) are all considered conspecific and referable to G. nigrolineatus . Nevertheless, the smooth to feebly keeled plantar scales in G. nigrolineatus from Gabon and Congo is in contrast to the moderately to strongly keeled scales in populations referable to G. intermedius (e.g. FitzSimons 1943), including those from Mozambique (e.g. TM 80959 and the other specimens listed in Appendix I) as discussed above.

The minium red to vermillion flanks (with pale spots or bars) of adult eastern G. nigrolineatus (= G. intermedius ) differ from the light and dark barred or mostly brown flanks of G. flavigularis (see descriptions and images in Jacobsen 1989; Branch 1998; Spawls et al. 2002; Alexander & Marais 2007). It should be noted however, that according to Broadley (1966), G. flavigularis from Mozambique and adjacent parts of Zimbabwe have vermillion flanks like G. nigrolineatus (= G. intermedius ), although only in areas of allopatry. The same colour pattern has been recorded in G. flavigularis from eastern Limpopo Department and eastern North West Province, South Africa, where the underside of the head is blue-grey in males (Jacobsen 1989). The possibility that such populations represent unique evolutionary lineages was not investigated in the present study, although some genetic structuring is evident within G. flavigularis ( Fig. 1).

According to Loveridge (1942), the scales on the flanks of G. nigrolineatus (= G. intermedius ) are striated, keeled, or more-or-less smooth, whereas those of adult G. f. flavigularis are smooth. For southern African material, FitzSimons (1943) noted that the laterals of G. nigrolineatus (= G. intermedius ) are keeled and sometimes feebly striated, while those of G. flavigularis are smooth or feebly keeled and striated. However, Loveridge (1942: 515) also noted that in his “ill-defined race” G. flavigularis fitzsimonsi (a synonym of G. flavigularis ) the laterals were striated and keeled, although occasionally almost smooth, whereas the prefrontals were in broad contact. The latter two features are consistent with G. nigrolineatus . However, Loveridge (1942: 515) noted that his new subspecies had a short head (head length into SVL 4.75 times in young to 6 times in adults) as in G. f. flavigularis , and “should not be confused with G. f. intermedia …which, from his [Lönnberg 1907] figure, is a synonym of the long-headed G. n. nigrolineatus ”. Head length into SVL was 4.7–5.0 times for the two Congo specimens examined, and 4.0–5.0 times (4.8–5.0 for three adults with SVL> 100 mm, 4.0–4.6 for seven juveniles with SVL <80 mm) for the nine Gabon samples. The vouchered Mozambique sample of G. intermedius (TM 80959) was similar with head length into SVL 4.4 times. Therefore, we conclude that G. f. intermedia Lönnberg, 1907 is conspecific with eastern populations currently referred to G. nigrolineatus Hallowell, 1857 and which we now refer to G. intermedius .

In light of the phylogenetic and morphological differences mentioned above, we suggest that populations in Gabon and lower Congo (including Kouilou region) are all referable to G. nigrolineatus , and that all East and Southern African populations ( Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa) formerly identified as G. nigrolineatus be referred to G. intermedius . Accurate determination of geographical boundaries for these two species, especially in Central Africa ( Angola, D.R.C., Zambia, northern Botswana, northern Namibia), will require additional sampling on a finer scale than presently available, as well as additional morphological examination of specimens from throughout their extensive ranges. The assignment of Angolan specimens referred to G. nigrolineatus (e.g. Hellmich 1957; Manaças 1963; Parker 1936; Schmidt 1933; Laurent 1964), and their relationship to G. multilineatus , remains problematic.

Gerrhosaurus bulsi , sister taxon to all other taxa in the G. nigrolineatus complex, is well supported as a distinct lineage ( Fig. 1), and is easily identifiable from others in the complex by its distinct, largely uniform, brown or grey dorsal colour pattern in adults ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ). The type locality of G. b ul s i is Dundo, north-east Angola; the species also occurs in Zambia and the D.R.C. (Laurent 1954, 1964; Broadley 1966; Haagner et al. 2000; Broadley & Cotterill 2004; Adolphs 2006, 2013). Our samples were from Kalumbila Village in North West Province, Zambia; and near Lake Carumbo, Angola, i.e. about 100 km WSW of the type locality ( Table 1).

Gerrhosaurus auritus appears to be closely related to G. nigrolineatus , but morphologically it is distinguishable by its broad and crescentic (versus narrow) tympanic shield, smooth (versus keeled) lateral scales, and lack (versus presence) of distinct dorsolateral stripes in adults (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943; Broadley 2007). Its back is usually pale brown, often with 3–4 narrow, pale, black-bordered dorsolateral stripes (Broadley 1966; Branch 1998; Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 ). The type locality of G. auritus is Ondonga, Ovamboland, northern Namibia, but the species also occurs in southern Angola, south-western Zambia (where our single sample is from― Table 1), Botswana, western Zimbabwe and northern Limpopo Province in South Africa (Loveridge 1942; FitzSimons 1943; Broadley 1966; Visser 1984a; Broadley & Rasmussen 1995; Branch 1998; Broadley & Cotterill 2004; Adolphs 2006, 2013; Bates et al. in press.). The four species G. nigrolineatus , G. intermedius , G. auritus and G. bulsi , and possibly the morphologically and geographically allied form G. multilineatus (if valid, see below), constitute the ‘ G. nigrolineatus species complex’ with a widespread distribution in Africa.

Status of Gerrhosaurus multilineatus

The taxonomic status of G. multilineatus has been confused in the literature and remains uncertain. According to Haagner et al. (2000), “Broadley (1999) notes that the taxon G. multilineatus Bocage is based on a hybrid specimen. The name is therefore unavailable.” However, this was in fact a reference to an unpublished manuscript (D.G. Broadley in litt. 8 February 2012). According to Article 17.2 of the Code (ICZN 1999), even if the specimen was a hybrid, the name would in fact still be available.

In his description of G. multilineatus , based mainly on colour pattern, Bocage (1866a) noted that this form was similar to G. nigrolineatus , of which it may be merely a well characterised variety. Loveridge (1942) and FitzSimons (1943) subsequently relegated G. multilineatus to the synonymy of G. nigrolineatus . Although the type series of G. multilineatus (Duque de Bragança district [region], interior of Angola) was destroyed in the 1978 fire at Museu Bocage in Lisbon (Almaca & Neves 1987; Madruga 2012), we examined colour photographs of two ‘virtual’ topotypes (‘Duque de Bragança’) in the collection of the Natural History Museum (London). In terms of morphology and colour pattern (e.g. Figs 14 View FIGURE 14 & 15 View FIGURE 15 ) these specimens agree well with Bocage’s description. Although somewhat faded, cream coloured longitudinal stripes, with black borders, are present on the back, at least anteriorly. In BM 1904.5.2.32 there are dorsolateral stripes as well as a vertebral stripe ( Fig. 15 View FIGURE 15 ), as described by Bocage (1866a), whereas BM 1904.5.2.33 appears to have only dorsolateral stripes. The two specimens (about 170 mm and 150 mm SVL respectively) appear to be adults.

Laurent (1964) presented data for a large series of Gerrhosaurus from Angola which he referred to G. bulsi , contrasting these with a specimen from ‘Mayombe’ (may refer to the region from western Gabon southwards to western D.R.C., or to the Mayombe massif in Republic of Congo) which he referred to G. nigrolineatus nigrolineatus (because of its “blackish colouration”, p. 54), and four specimens from Pweto at the northern end of Lake Mweru in Katanga Province, D.R.C. which he referred to G. nigrolineatus intermedius . Laurent (1964: 54) noted that if the “ type ” of G. multilineatus was a young G. bulsi , the former name would have priority. According to Laurent (1964), young G. bulsi have a (striped) dorsal colour pattern similar to that of G. nigrolineatus (striped throughout life), but this pattern gradually fades and adult G. bulsi (13 cm SVL and larger) display a uniformly coloured and unpatterned dorsum ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 ). However, juvenile G. bulsi are not always striped: PEM R19475 from Lake Carumbo base camp in Angola ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 ), used for the molecular analysis, is brown with dark bands on the flanks and scatterered dark scales on the back, but it lacks any distinct dorsolateral (and vertebral) stripes, whether pale, black, or pale with black borders. Bocage’s (1866a) description of G. multilineatus was based on “three specimens of identical colour” (see Bocage 1866b: 44, a paper preceding the description). However, although Bocage (1866a) described all three syntypes as having olive backs with narrow yellow, black-bordered dorsolateral and vertebral stripes, he noted that the largest (apparently adult) specimen (123 mm SVL + 250 mm tail length) also had three similar but narrower stripes in each of the interspaces between dorsolateral and vertebral stripes, while in the other (smaller) specimens these intermediate stripes were replaced by black markings. From the available information it therefore seems that, at the very least, the largest specimen examined by Bocage (1866a) is not conspecific with G. bulsi (adults are unstriped). Whether or not Bocage’s specimens are referable to G. nigrolineatus , or a separate species, is unclear. However, the two topotypes of G. multilineatus do not have the very large heads typical of adult G. nigrolineatus , G. intermedius and G. auritus (i.e. head length into SVL five times or less; see Loveridge 1942, FitzSimons 1943). Based on scaled photographs of BM 1904.5.2.33 and BM 1904.5.2.32, head length is contained in SVL about 5.6 and 5.7 times, respectively.

Resolution of the taxonomic status of G. multilineatus must await the collection of material from the type locality for molecular analysis, and a detailed morphological evaluation of the complex.

Status of Gerrhosaurus flavigularis

While there is some sub-structuring within G. flavigularis ( Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 ), with populations from Eastern South Africa, Northern South Africa and East Africa ( Table 1) all identifiable as subclades in the phylogeny ( Fig. 1), we consider this assemblage a single species pending a more detailed phylogeographical and morphological analysis. The type locality for G. flavigularis of “South [or southern] Africa” (see Bauer et al. 1994) was restricted to an area in the central Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (Bauer 2000), but the species occurs extensively from the Western Cape ( South Africa) northwards through southern and eastern Africa to Ethiopia (Loveridge 1942). Although not sampled for this study, should the apparently disjunct population in the Western and Eastern Cape Provinces be found to represent a unique lineage, the name G. flavigularis would be applicable to it. If the other population in southern and East Africa proves to be a separate species, the name Gerrhosaurus bibroni Smith, 1844 is available.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.