Grampus griseus (G. Cuvier, 1812)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6610922 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6611068 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BD4CCC61-7630-FFF8-FFD4-FCF3E18EF8FE |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Grampus griseus |

| status |

|

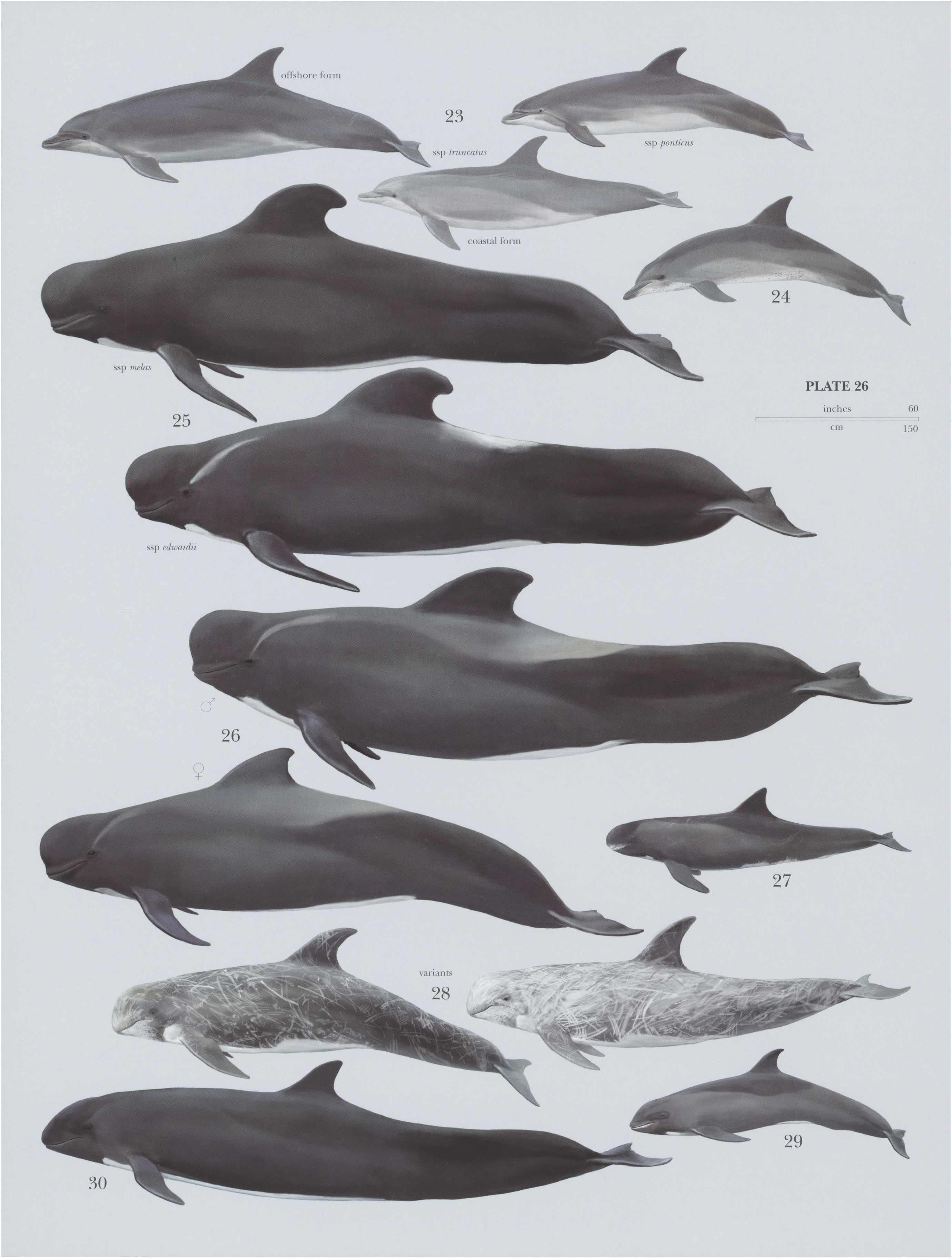

28. View On

Risso’s Dolphin

French: Grampus / German: Rundkopfdelfin / Spanish: Calderon gris

Other common names: Grampus, Gray Dolphin, Gray Grampus, Risso’s Grampus, White-headed Grampus

Taxonomy. Delphinus griseus G. Cuvier, 1812 View in CoL ,

“envoyé de Brest,” Finistere, France.

This species is monotypic.

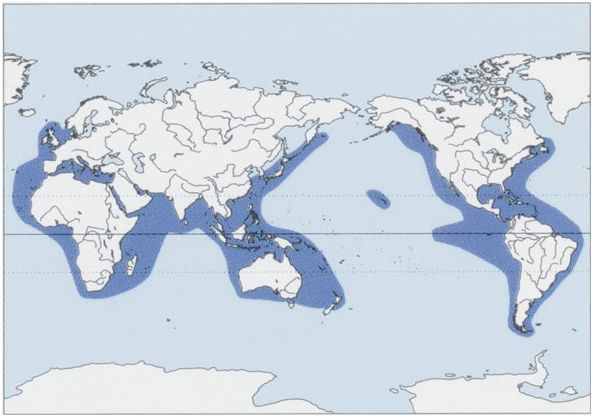

Distribution. Worldwide in tropical to temperate tropical to temperate oceanic waters between ¢.60° N and 60° S including the North Sea, Mediterranean Sea, and northern Gulf of Alaska. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 380- 410 cm; weight 400-500 kg. There is no notable sexual dimorphism in Risso’s Dolphins. Neonates are 110-150 cm long and weigh 20-30 kg. Risso’s Dolphin has robust body shape; narrow tailstock; and bulbous, squarish head, with barely discernable beak. It has unique, deep vertical cleft or groove that runs along anterior side of rostrum and melon. Flippers are sickle-shaped, and dorsal fin is tall and falcate, positioned about halfway along body. Risso’s Dolphin is one of the most heavily scarred species of delphinids, with white scratches and blotches covering most of body. These scars, which are healed wounds from squid beaks and suckers, or teeth from other Risso’s Dolphins, contrast with underlying dark to pale-gray skin. White patches are found on ventral body between pectoral fins and around urogenital region. Young individuals are usually darker than adults, sometimes with a brownish tinge, and have few scars. Skin of young Risso’s Dolphins darkens to a near black before becoming paler at sexual maturity. Only dorsal fin may remain darkly colored in adulthood. There are 0-2 (generally unerupted) pairs of teeth in upper jaw and 2-7 pairs in lower jaw. Teeth are often worn or missing in older individuals.

Habitat. Primarily deep waters (400-1000 m) offshore from the continental slopes, where sea-surface temperature is 15-25°C. Risso’s Dolphin is rarely found in water less than 10°C, which results in seasonal population movements in some parts of the world. It prefers habitat over escarpments and steep seafloor topography, resulting in an overall patchy distribution that loosely outlines continents and major oceanic islands. There is evidence, however, that habitat use by Risso’s Dolphin is coordinated to avoid spatial overlap with Cuvier’s Beaked Whale (Ziphius cavirostris) or temporally with the Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus). Risso’s Dolphin was once uncommon off southern California, but a permanent increase in its abundance occurred in the region after the 1982-1983 El Nino.

Food and Feeding. Risso’s Dolphin feeds primarily on cephalopods, which explains their habitat preference for steep bottom slopes. These areas are often subject to upwelling and are typically productive and ideal for hunting vertically migrating, mesopelagic prey. Because cephalopods usually migrate closer to the surface at night with the deep scattering layer, Risso’s Dolphin is a nocturnal feeder. Commonly documented prey include common octopus (Octopus vulgaris), greater argonaut ( Argonauta argo), neon flying squid ( Ommastrephes bartrami), European flying squid ( Todarodes sagittatus), reverse jewel squid ( Histioteuthis reversa), and various other species in the families Argonautidae , Ommastrephidae , Histioteuthidae , and Onychoteuthidae .

Breeding. Breeding of Risso’s Dolphin appears to peak during summer in the North Atlantic Ocean and occurs throughout the year in the North Pacific Ocean. Sexual maturity is attained when both sexes reach body lengths of 260-277 cm. This is thought to correspond to ¢.8-10 years of age for females and c.10-12 years for males. Gestation is thought to be 13-14 months, and reproductive females have an offspring every 2-4 years. Individuals may live up to 35 years.

Activity patterns. Risso’s Dolphins occasionally behave energetically by breaching or “porpoising” while traveling and surfing on swells, but they more often surface slowly. They are nocturnal foragers, but there are currently no robust data on diving patterns or activity budgets. Risso’s Dolphin is not shy of boats and will occasionally bow-ride or surf in wakes.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Groups are typically 10-50 individuals, but groups of up to 4000 individuals have been documented. Social subunits within groups may be segregated by sex and age, and long-term bonds may form among groups of 3—12 individuals. These bonds may be among individuals ofthe same or opposite sex. Juveniles remain in their mother’s group until sexual maturity, and mature males likely move more frequently among groups than females do. Groups of Risso’s Dolphin may temporarily associate with individuals of other cetacean species, including other delphinids, such as the Pacific White-sided Dolphin ( Lagenorhynchus obliquidens ), Fraser's Dolphin ( Lagenodelphis hose), or the Northern Right-whale Dolphin ( Lissodelphis borealis ), and larger species such as the Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus). Regular interspecific interactions and possibly persistent social bonds have been documented among Risso’s Dolphins, Striped Dolphins ( Stenella coeruleoalba ), and Short-beaked Common Dolphins ( Delphinus delphis ) in the Gulf of Corinth off Greece. Site fidelity of Risso’s Dolphins seems to be related to environmental constancy or seasonality. In less variable regions, such as off the Azores, there is greater residency than in areas where sea-surface temperature fluctuates widely during the year. Some populations of Risso’s Dolphins are known to migrate between the Mediterranean Sea in winter for breeding and waters off northern Scotland in summer for feeding. Similar seasonal breeding and feeding migrations are observed off England, South Africa, and Japan.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red List. The subpopulation of Risso’s Dolphins in the Mediterranean Sea is listed as Data Deficient. There are currently no global estimates of abundance or population trends for Risso’s Dolphins, but combined threats suggest that a 30% reduction in its abundance over the next three generations (60 years) is unlikely. There are ¢.16,066 individuals in population off California, Oregon, and Washington, USA; 2351 individuals off Hawaii; 5500-13,000 individuals off Sri Lanka; 1514 individuals in the Sulu Sea; 20,479 off the eastern USA; 2169 individuals in the northern Gulf of Mexico; 83,300 individuals offJapan; and ¢.175,000 individuals in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Risso’s Dolphin is hunted by small-scale fisheries in Sri Lanka (up to 1300 dolphins taken annually) and Japan (250-500 dolphins taken annually) for food, fish bait, and fertilizer, but mercury levels in the meat of Risso’s Dolphins, as in most small cetaceans, are high enough to be considered unsafe for human consumption. Risso’s Dolphin also is taken incidentally in fisheries all over the world, including the North Atlantic Ocean, southern Caribbean, and offthe Azores, Peru, Taiwan, and Solomon Islands;it seems especially vulnerable to longline gear. As a deep-water forager, Risso’s Dolphin also may be vulnerable to loud underwater noise from military activities and seismic surveying. Stranding events of multiple cetacean species, including Risso’s Dolphin, in Taiwan in 2004-2005 coincided with a period of large-scale naval exercises. Whale watching also may be disruptive in some areas, such as the Azores, where Risso’s Dolphins spendsignificantly less time resting and socializing when whale-watching activities are greatest. Other threats include ingestion of and entanglement in marine debris, such as discarded fishing line and plastic garbage, and aggression from fishermen who view Risso’s Dolphins as pests or competitors.

Bibliography. Amano & Miyazaki (2004), Baird (2009a), Barlow (2006), Barlow & Forney (2007), Baumgartner (1997), Endo et al. (2005), Frantzis & Herzing (2002), Gémez de Segura et al. (2006), Hartman et al. (2008), Jefferson et al. (2008), Kruse et al. (1999), Mullin & Fulling (2004), Oztiirk et al. (2007), Taylor et al. (2008d), Visser et al. (2011), Wang & Yang Shihchu (2006, 2007).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.