Sotalia fluviatilis (Gervais & Deville, 1853)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6610922 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608644 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BD4CCC61-7620-FFF7-FFD0-F364E770F921 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Sotalia fluviatilis |

| status |

|

13. View On

Tucuxi

Sotalia fluviatilis View in CoL

French: Dauphin tucuxi / German: Amazonas-Sotalia / Spanish: Tucuxi

Other common names: Brazilian Dolphin, Gray Dolphin, Gray River Dolphin

Taxonomy. Delphinus fluviatilis Gervais & Deville View in CoL in Gervais, 1853,

Rio Maranon above Pebas, Loreto, Peru.

Taxonomy of this genus has been in flux for some time, and prior to 2007, only one species (S. fluviatilis ) and two subspecies, a riverine type ( fluviatilis ) and a coastal type ( guianensis ), were recognized. An accumulation of genetic evidence, in addition to ecological and morphological differences, supports separate species status for these two types. Monotypic.

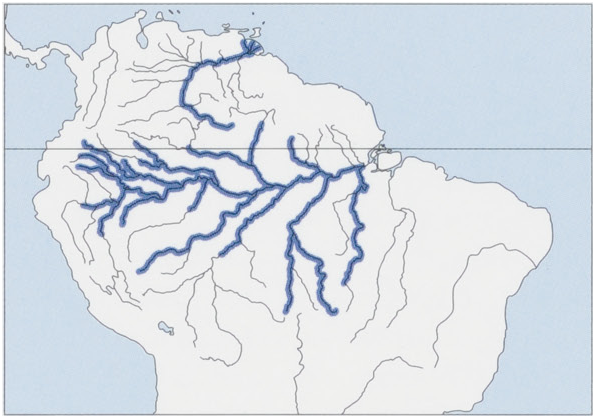

Distribution. Limited to the Amazon River Basin and most ofits tributaries in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. It may also extend into the Orinoco River system in Venezuela, but itis uncertain if sightings there were this species or the Guiana Dolphin (S. guianensus). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length up to 149 cm (males) and up to 152 cm (females); weight up to 52 kg. Neonates are thought to be 70-80 cm long. The Tucuxi is similar in appearance to bottlenose dolphins (7ursiops spp.), and it is smaller than its coastal counterpart, the Guiana Dolphin. Body shape of the Tucuxi is robust with long, narrow beak, wide flippers, and short, triangular dorsal fin. A visible crease separating melon and beak is characteristically absent in this genus. Most skin on dorsum is dark gray, with slight blue or brown tinge that fades into pale gray or white with pink tinge on belly and lower jaw. Dark gray band extends from behind eye to base of flipper. There tends to be more pale lateral pigmentation on posterior one-half of body and tail than in front of dorsal fin. Flukes and flippers are dark gray on both sides. There are 28-35 pairs of small, conical teeth in upperjaw and 26-33 pairs in lower jaw.

Habitat. Exclusively freshwater, riverine habitats (the only delphinid to be so limited). The Tucuxi is found in the Amazon River Basin and may be found as far inland as southern Peru, eastern Ecuador, and south-eastern Colombia. Water turbidity and pH do not appearto affect distribution of the Tucuxi, and sightings have been made in all three of the Amazon Basin’s main river types: whitewater (sedimentrich), clearwater, and blackwater (acidic). Nevertheless, unlike the Amazon River Dolphin (/nia geoffrensis), the Tucuxi generally does not enter flood zones, and it has not been observed in rivers less than 3 m deep or in lakes less than 1-8 m deep. Tucuxis are less abundant in rapids and turbulent water and are most common at river junctions where current is mild. Impassable shallow areas, rapids, and waterfalls likely segment populations of Tucuxis throughout the Amazon Basin. Areas where whitewater and blackwater mix tend to be ecologically productive and seem especially preferred by the Tucuxi. Habitat hotspots include areas within 200 m of riverbanks, riverjunctions, and lakes.

Food and Feeding. Some 30 species of freshwater fish in 13 families have been documented as prey of the Tucuxi; curimatids (toothless characins), sciaenids (croakers), and Siluriformes (catfish) seem to be preferred. The Tucuxi will forage only for relatively small species and age classes, usually no longer than 35 cm. Foraging activity is more frequently seen during the low-water season when fish become confined to the Amazon River Basin’s major tributaries. During the flood season, prey species move into flood zones to feed, but unlike the Amazon River Dolphin, the Tucuxi does not enter these areas. Tucuxis may forage alone or in groups.

Breeding. Breeding peaks during the low-water season in September—November. Gestation is c¢.11 months. Sexual maturity is reached at lengths of 132-134 cm for males and c.140 cm for females. A high ratio of testes mass to body mass (c.5%) suggests that the Tucuxi has a promiscuous mating system, dependent on sperm competition. Tucuxis may live at least 30-35 years; a recent estimate suggests that some individuals live beyond 40 years.

Activity patterns. Feeding and traveling of Tucuxis are the most commonly observed behaviors, and individuals may be observed “porpoising” while swimming at faster speeds. Movements of the Tucuxi into lake systems from rivers appear to fluctuate diurnally; groups tend to move into lakes twice daily, in the early morning and late afternoon. Dives last 1-5-2 minutes, and individuals generally spend very little time at the surface. The Tucuxi is vocally active and has a wide repertoire of whistles and echolocation clicks. Variation in click structure over the Amazon River Basin may reflect geographical variation and population structure. Tucuxis are not known to bow-ride and rarely approach boats, but they are sometimes observed to spy-hop and perform somersaulting leaps.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Tucuxi has a social structure similar to that of the Guiana Dolphin. Groups of one to four individuals are most common, but groups of up to 20 individuals have been reported. Group sizes are larger on average at riverjunctions and in lakes. Although the Tucuxiis sympatric with the Amazon River Dolphin, the two species are rarely observed to interact. Maximum known movement of Tucuxis is 130 km, and some individuals move up to 56 km/day. Their distribution is primarily driven by seasonal fluctuations in river levels. Lake systems that may be too small or restricted by channels that are too shallow during the lowwater season become accessible during the flood season. The Tucuxi also spends more time at river junctions during the low-water season, likely because these are strategic places to forage.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Data Deficient on The IUCN Red List. Because the Tucuxi is now recognized as a separate species, distinct from the Guiana Dolphin,its endemism to the Amazon River Basin has increased conservation importance. Data evaluating risks of population decline are scarce, and there are currently no estimates of total abundance. Local estimates of abundance and density are often inconsistent and arrived at by varying methods. Some of the latest abundance estimates surveying the largest area of the Amazon River Basin (2704 km) are 1545 individuals in Colombia, 2205 individuals in Venezuela (although whether dolphins in the Orinoco are Tucuxis or Guiana Dolphins is uncertain), 1319 individuals in Peru, and only 19 individuals in Ecuador. These dolphins tend to be most abundant in lakes and riverjunctions and within 200 m of riverbanks, so such areas have been suggested as critical habitat for both the Tucuxi and the Amazon River Dolphin. Proximity of Tucuxis to human activity means they are especially vulnerable to threats from fisheries, boat traffic, contaminants, and residential and industrial waste; harmful interactions with local fisheries are of greatest concern. Direct competition between Tucuxis and these fisheries is minimal because not all preferred prey species of the Tucuxi have high commercial value. Only 14 of 30 commercially viable prey species in the Amazon River have been documented as Tucuxi prey. Tucuxis are not directly caught due to local superstitions surrounding them, but increased fishing intensity in the Amazon River Basin has led to increased rates of incidental catch. Tucuxis seem especially susceptible to entanglement in monofilament gillnets, which are most commonly used in the high-productivity areas where they most abundant. Tucuxis are also often caught in seine nets and shrimp traps. River damming for hydroelectric projects contributes to habitat degradation and has the potential to disrupt gene flow among Tucuxi populations in the Amazon River Basin. Mitochondrial genetic diversity of the Tucuxi throughout its distribution appears to be high, suggesting a fairly large effective population size and a high amount of female gene flow; connectivity among regions of the Amazon River Basin is important for continued population health. Up to 200 dams have been proposed along the Amazon River's major tributaries, which would fragment populations of many species, including the Tucuxi, the Amazon River Dolphin, and their prey. Industrial and agricultural activity in the Basin also contributes to both habitat degradation and pollution. Several potential pollutants, which are banned elsewhere, continue to be used in South America. For example, mercury is still used to refine fluvial gold, and Brazil is one of the world’s top pesticide consumers. Such pollutants enter the Amazon River Basin and food webs via runoff, and recent studies in Brazil indicate high levels of PCBs and PBDEs in prey species of the Tucuxi; data on levels of such pollutants in Tucuxis are scarce. Noise pollution may also be a growing concern because use of outboard engines in the Amazon River Basin has increased, and in some areas, explosives are illegally used for fishing. Other threats may include boat collisions, oil spills, and overexploitation of prey species.

Bibliography. Caballero et al. (2007, 2010), Cunha & Watts (2007), Faustino & da Silva (2006), Flores & da Silva (2009), Gomez-Salazar et al. (2012), Jefferson et al. (2008), Martin et al. (2004), May-Collado & Wartzok (2010), McGuire (2010), McGuire & Henningsen (2007), Monteiro-Neto et al. (2000), Quinete et al. (2011), Reeves et al. (2003), Rosas et al. (2010), Secchi (2010c), da Silva & Best (1994), Vidal et al. (1997), Zapata-Rios & Utreras (2004).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.