Cephalorhynchus hectori, Van Beneden, 1881

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6610922 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608658 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BD4CCC61-760C-FFC3-FADE-FB68EF06FB24 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Cephalorhynchus hectori |

| status |

|

36. View On

Hector’s Dolphin

Cephalorhynchus hectori View in CoL

French: Dauphin de Hector / German: Hector-Delfin / Spanish: Delfin de Hector

Other common names: Little Pied Dolphin, New Zealand Dolphin, White-headed Dolphin; South Island Hector’s Dolphin (hectori); Maui's Dolphin, North Island Hector’s Dolphin (maui)

Taxonomy. Electra hectori Van Beneden, 1881 ,

“capturé sur la cote nord-est de la Nouvelle-Zélande [= north coast, New Zealand].”

There are four populations of C. hector that appear to be demographically isolated from each other. One of these, found along coasts of New Zealand’s North Island, has recently been given subspecific status based on genetic distinctiveness and geographic separation. Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

C.h.hectoriVanBeneden,1881—threepopulationsdistributedaroundNewZealand'sSouthIsland.

C. h. maui Baker, Smith & Pichler, 2002 — one population limited to the NW coast of New Zealand’s North Island. View Figure

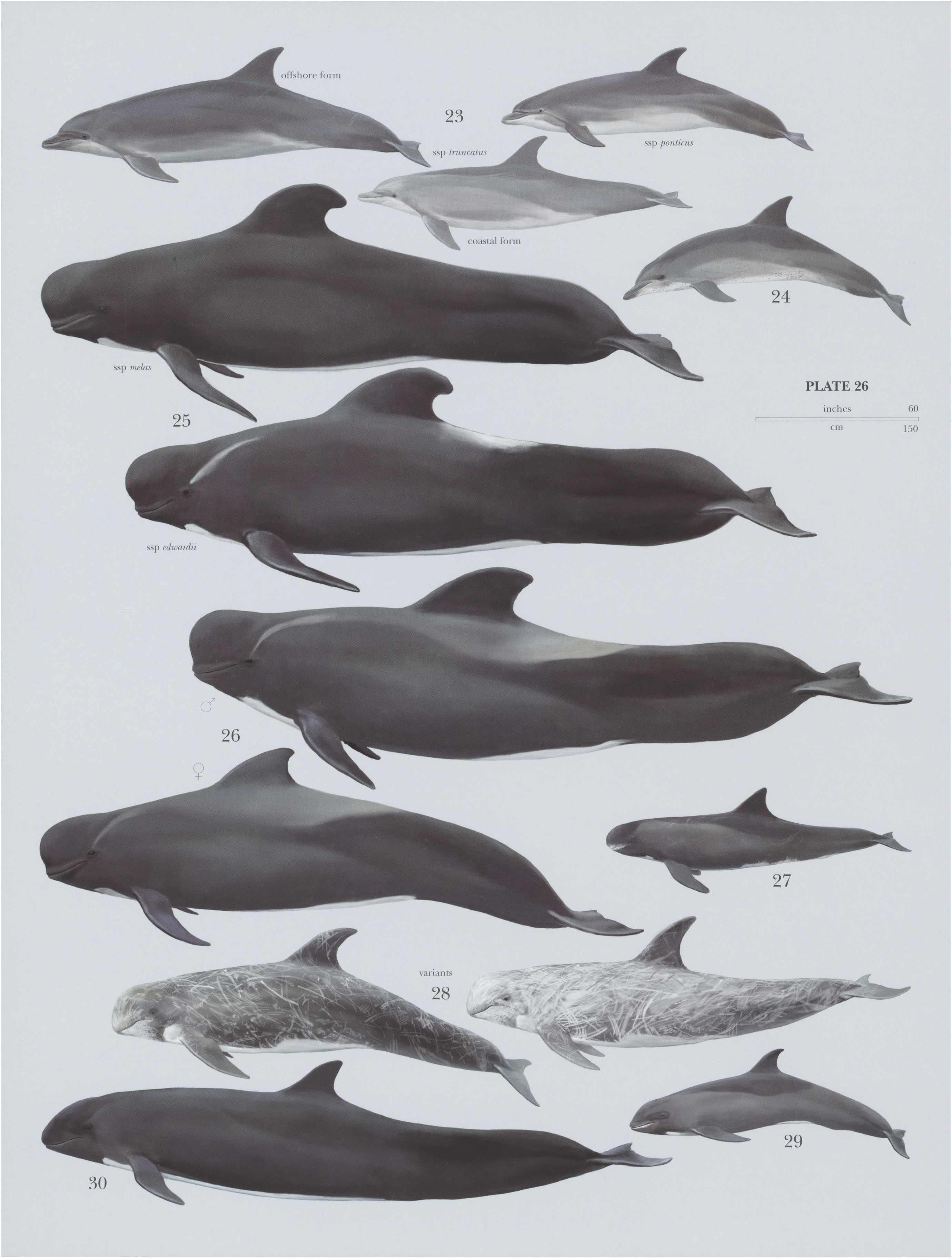

Descriptive notes. Total length 144 cm (males) and 153 cm (females); weight up to 50 kg ( hectori ). Total length 146 cm (males) and 163 cm (females); weight up to 65 kg (maui). Neonates are 60-70 cm. Like other species of Cephalorhynchus , Hector’s Dolphin has robust, stocky build and blunt, barely discernable beak. Dorsal fin is distinctively large, broad, and rounded, and flippers are paddle-shaped with rounded tips. Most of body is pale gray, but flippers, dorsalfin, flukes, and most of face are darker gray to black. Dark band also arches across head from above eyes to just behind blowhole. Throat and belly are white, except for dark-gray patch that may extend across chest between flippers. Slender white lobes extend up onto lower flanks from ventral area roughly in line with dorsal fin’s anterior edge. There are also small white patches behind flippers in “armpit” area. Gray patch may cover urogenital area of male “South Island Hector’s Dolphins” (C. A. hector). This patch is smaller or may be absent in female South Island Hector’s Dolphin and both sexes of “Maui’s Dolphins” (C. A. maui). There are 24-31 pairs of teeth in each jaw.

Habitat. Prefer shallow, turbid, coastal waters less than 8 km from shore, less than 75 m deep, and 6-22°C; most abundant at temperatures greater than 14°C and depths less than 39 m. Hector’s Dolphin is endemic to New Zealand. The South Island Hector’s Dolphin is most common along east and west coasts of South Island. Most of the population (90%) of the Maui’s Dolphin is concentrated between Manuaku Harbor and Port Waikato (c.40 km) on the west coast of North Island. Hector’s Dolphins are absent from Fiordland and the Cook Strait separating North Island and South Island, where waters are deeper than 300 m.

Food and Feeding. Hector’s Dolphin is an opportunistic forager, preying on a wide variety of benthic and pelagic fish and cephalopods. These include yellow-eye mullet ( Aldrichetta forsteri), kahawai (Arripis trutta), arrow squid ( Nototodarus sp. ), ahuru (Auchenoceros punctatus), red codling (Pseudophycis bacchus), and New Zealand sand stargazer (Crapatulus novaezelandiae). Eight species comprise 80% of the diet of the South Island Hector’s Dolphin on the east coast of South Island. On the west coast, only four species comprise 80% of their diet, suggesting that their diet is more varied on the east coast.

Breeding. Mating and breeding season of Hector’s Dolphins occur in spring and summer. Gestation lasts 10-11 months. Females reach sexual maturity at 6-9 years and males at 5-9 years. The birthing interval is 2—4 years. Maximum known age of Hector’s Dolphin is 22 years.

Activity patterns. Little is known about activity budgets and diving patterns of Hector’s Dolphin, but they are known to behave energetically, especially in large groups. Breaching, chasing, and tail slapping are commonly observed, and individuals will often ride bow waves of boats. Groups of Hector’s Dolphins are usually dispersed and not tightly coordinated.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Hector’s Dolphin usually lives in groups of 2-8 individuals, but larger aggregations of up to 50 individuals have been reported. These large groupings occur when several small groups temporarily associate. Social structure is fluid, and long-term associations are rare. Like other species of Cephalorhynchus , Hector’s Dolphin generally produces narrow-band, high-frequency echolocation clicks in a range similar to porpoises ( Phocoenidae ). Hector’s Dolphin appears to have high site fidelity in small, localized areas throughout its distribution, and individuals appear to move along 30-106 km of coastline throughout the year. Short-range, diurnal movement patterns have been documented on the west coast of South Island. Individuals there tend to move slightly offshore during late afternoon and early evening, and return to inshore harbors and bays in morning. The population inhabiting the south-eastern coast of South Island does not show any diurnal movement patterns. In some areas, Hector’s Dolphin may also show some seasonal fluctuations in abundance, which likely reflect migration between more protected inshore waters in summer for breeding and more offshore waters (sometimes beyond 30 km from shore) in winter for feeding.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Hector’s Dolphin has one of the smallest distributions of any cetacean species, and a recent population viability analysis estimated a 74% decline in abundance between 1970 and 2009. The Maui’s Dolphinis classified as Critically Endangered because of very low abundance (c.111 individuals), concentration of most of the population in a small area, and an ongoing and projected decline of more than 80% in just three generations (c.39 years). Abundance of the South Island Hector’s Dolphin was estimated at 7270 individuals in 2004-2005 and more recently at 7873 individuals in 2012. The most concerning threat to Hector’s Dolphinis incidental catch in recreational gillnets. In the 1980s, at least 57 ind/year were killed incidentally, and most strandings are ofsingle individuals that bear injuries consistent with entanglement. Incidental catch in trawl nets has also been reported. Five marine mammal sanctuaries have been designated along coasts of New Zealand since then. The first of these, Banks Peninsula Marine Mammal Sanctuary, was created in 1989, and an extension toits offshore boundary from c.7 km to 22 km was implemented in 2010 to accommodate offshore movements of Hector’s Dolphins during winter. Stricter gillnet legislation was also enacted in 2008, banning gillnet use within 4-13 km ofshore along some areas of coastline. Prior to 2008, 110-150 Hector’s Dolphins were caught incidentally per year. Use of “pingers” in some areas has been moderately effective at protecting Hector’s Dolphins from fishing gear. Nevertheless, both subspecies are projected to continue declining unless fisheriesrelated mortality is brought to near zero. Without mortality caused by incidental catch, abundance could increase to ¢.15,000 individuals in the next 50 years. Because Hector’s Dolphins live close to human settlements, pollution may also be a threat. Moderate-tohigh concentrations of persistent organochlorine pollutants (e.g. DDT and PCBs) and heavy metals (e.g. mercury and cadmium) have been recorded in body tissues of Hector’s Dolphins, but their contribution to mortality and fecundity is currently unknown.

Bibliography. Baker et al. (2002), Bejder & Dawson (2001), Brager, Dawson et al. (2002), Brager, Harraway & Manly (2003), Dawson (2009), Dawson et al. (2001), Jefferson et al. (2008), Rayment et al. (2010), Reeves, Dawson et al. (2000, 2008), Slooten (2007), Slooten & Davies (2012), Slooten & Dawson (1994), Slooten, Dawson et al. (2006), Slooten, Rayment & Dawson (2006), Stone et al. (1997).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |