Lutnes Cameron, 1884

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4415.2.5 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:862FFD70-CB4F-45EA-BF25-FED1B621842F |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5974373 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/914F713C-D766-FFB8-FF7D-FC35148BCA6F |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Lutnes Cameron |

| status |

|

Lutnes Cameron, 1884: 125 View in CoL . Type species: Lutnes ornaticornis Cameron View in CoL , by subsequent designation of Ashmead, 1904a: 289. Parooderelloides Girault, 1913: 67 –68. Type species: Parooderelloides biguttata Girault View in CoL , by monotypy and original designation. Synonymy by Gibson, 1995: 217, 219.

Argaleostatus Gibson, 1995: 147 View in CoL –150. Type species: Eupelmus testaceus Cameron View in CoL , by original designation. New synonymy.

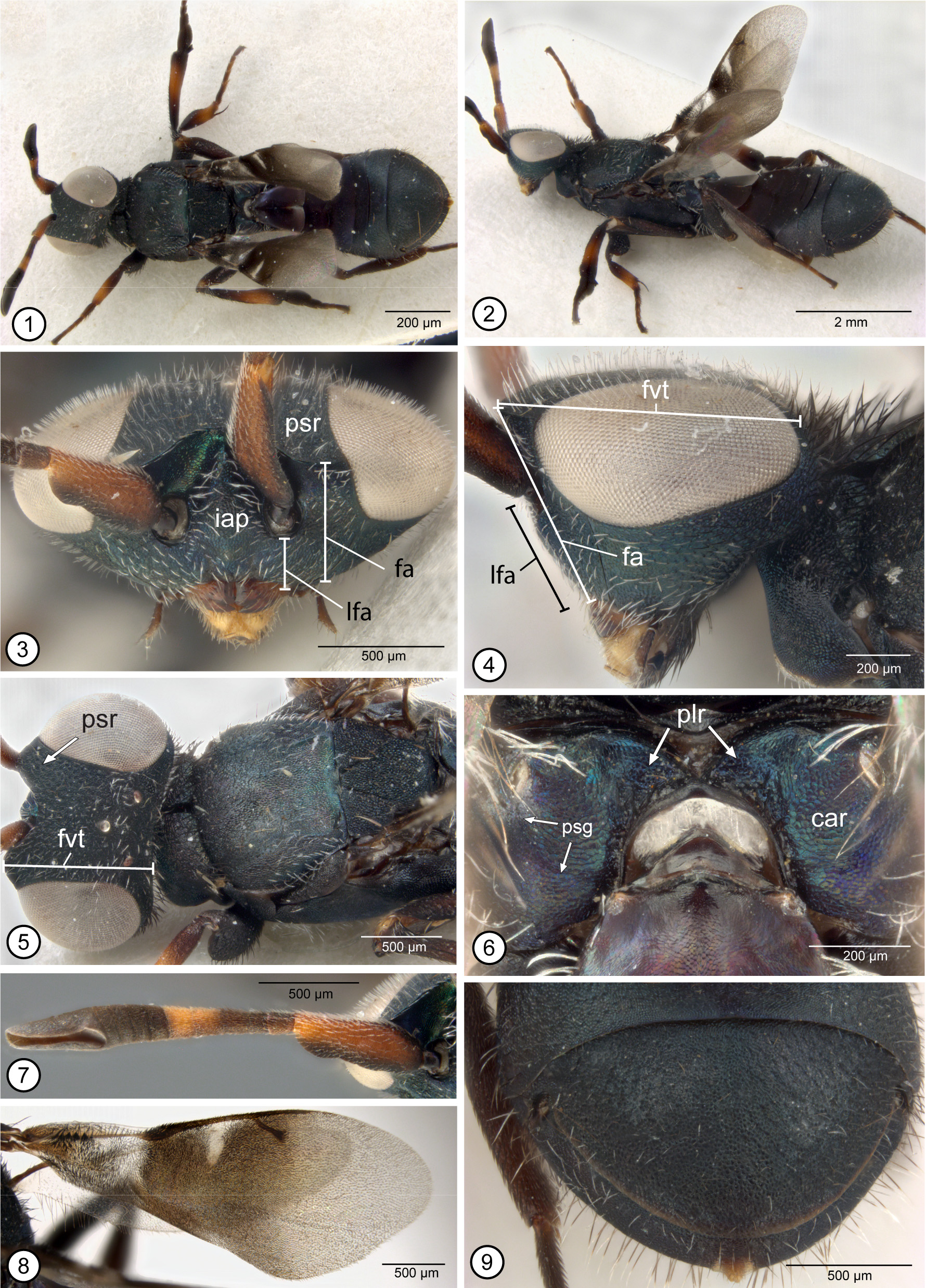

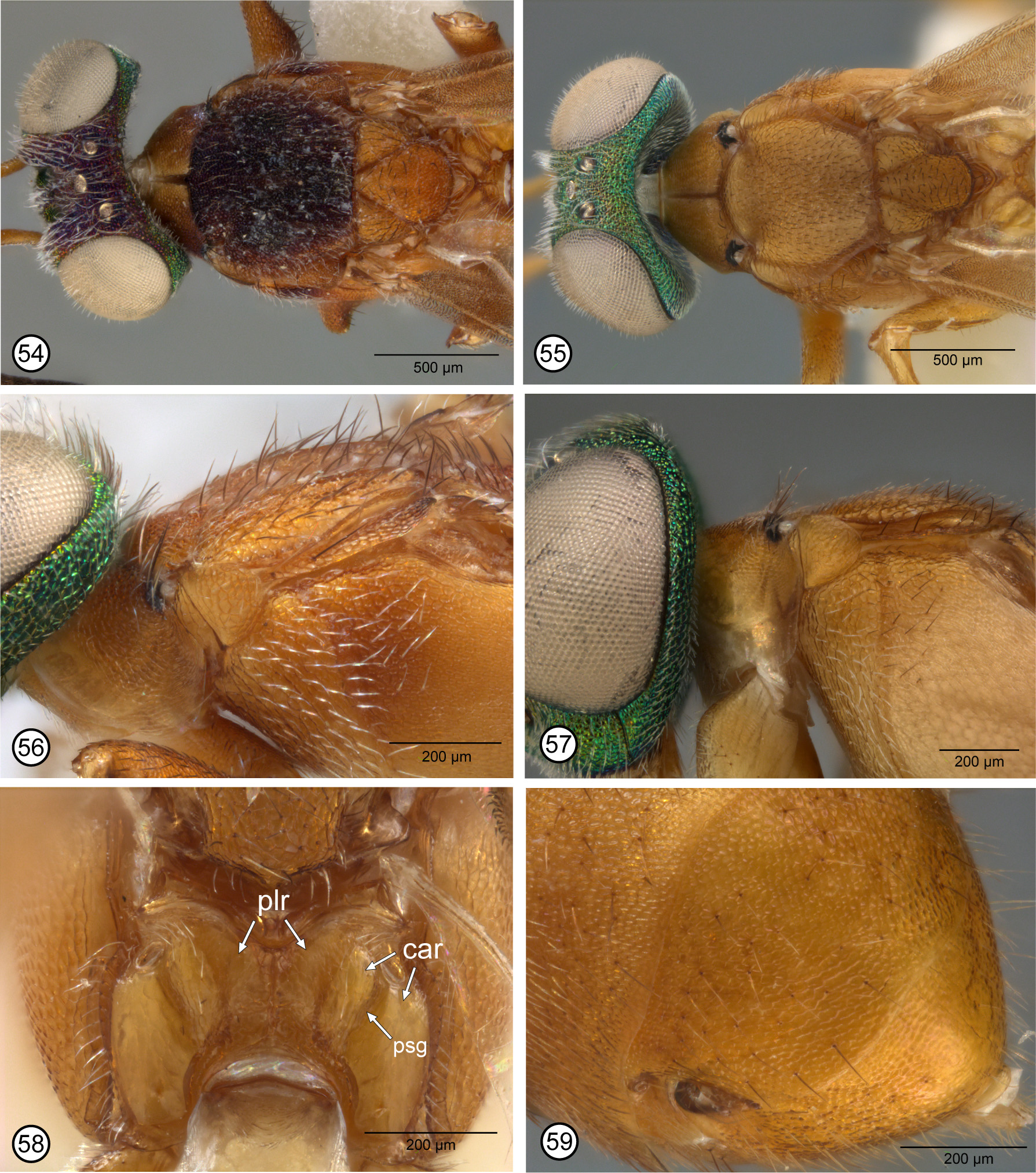

Description. FEMALE. Mandibles bidentate, with acute ventroapical tooth and broad, truncate to slightly incurved dorsoapical margin ( Figs 30 View FIGURES 28–36 , 47 View FIGURES 46–53 ). Head with frontal surface mostly punctate-reticulate to reticulaterugulose; in lateral view variable in shape, from lenticular (Neo, e.g. Fig. 29 View FIGURES 28–36 ) to bluntly- (Neo, e.g. Fig. 11 View FIGURES 10–18 ) or acutely-subtriangular (Afro, Fig. 4 View FIGURES1–9 ); scrobal depression with carinate lateral margin recurved toward inner orbit ventrally ( Figs 3 View FIGURES1–9 , 13 View FIGURES 10–18 , 21 View FIGURES 19–27 , 30 View FIGURES 28–36 , 39, 40 View FIGURES 37–45 , 47 View FIGURES 46–53 ), though variably distinctly so, and with depression either not margined dorsally (Neo, e.g. Figs 39 View FIGURES 37–45 , 47 View FIGURES 46–53 ) or entirely carinate between inner orbits (Afro, Figs 3, 5 View FIGURES1–9 ); interantennal prominence, lower face at least in part, and parascrobal region ventrally with whitish-translucent lanceolate setae (Neo, e.g. Figs 13 View FIGURES 10–18 , 21 View FIGURES 19–27 , 40 View FIGURES 37–45 ) or with more hairlike white setae (Afro, Fig. 3 View FIGURES1–9 ). Eye setose. Antenna with scape more or less cylindrical and flagellum with apical four funiculars at least subquadrate or only apical funicular slightly transverse (Neo, e.g. Figs 12 View FIGURES 10–18 , 24 View FIGURES 19–27 ) or scape conspicuously compressed ( Fig. 3 View FIGURES1–9 ) and flagellum with apical four funiculars strongly transverse (Afro, Fig. 7 View FIGURES1–9 ). Pronotum sometimes without visible collar (e.g. Figs 10 View FIGURES 10–18 , 37 View FIGURES 37–45 ), sloped down from posterior margin and normally concealed by posterior of head, but if horizontal collar visible then transverse-triangular (lateral margins converging almost from posterolateral angle, Fig. 48 View FIGURES 46–53 ) to transversepentagonal (with short, subparallel margins posteriorly, Fig. 22 View FIGURES 19–27 ), but collar at least divided mediolongitudinally by furrow, not distinctly depressed on either side of furrow, and with variably conspicuous and extensive black setae (e.g. Figs 5 View FIGURES1–9 , 22 View FIGURES 19–27 ) or, much less commonly, white setae ( Fig. 42 View FIGURES 37–45 ) at least along posterior margin; propleuron and prosternum with black or white setae. Mesoscutum mostly coarsely sculptured, reticulate to punctatereticulate, though lateral flange more finely meshlike coriaceous-reticulate to transversely strigose; dorsally quite flat with lateral lobes only slightly convex relative to slightly concave median region, without conspicuously differentiated medial and lateral lobes (e.g. Figs 5 View FIGURES1–9 , 14 View FIGURES 10–18 , 42 View FIGURES 37–45 ) and often with a mixture of black hairlike setae and whitish hairlike to translucent, slender-lanceolate setae; lateral lobe at most longitudinally carinate within posterior half. Scutellar-axillar complex similarly sculptured as mesoscutum to more longitudinally reticulate-strigose; scutellum truncate along anterior margin but for distance less than half width of axilla. Specimen macropterous (fore wing extending about to apex of gaster) or brachypterous (fore wing at least extending distinctly over base of gaster, e.g. Figs 20 View FIGURES 19–27 , 51 View FIGURES 46–53 , but at most about half length of gaster, e.g. Fig. 29 View FIGURES 28–36 ); fore wing without linea calva and disc with mostly broadly lanceolate dark brown and/or orangish setae from basal fold to near apex of stv or pmv, but more hairlike brown setae beyond level of stv or pmv and usually with hyaline region(s) with white hairlike setae behind mv (e.g. Figs 8 View FIGURES1–9 , 16 View FIGURES 10–18 , 25 View FIGURES 19–27 ); costal cell dorsally setose (Neo) or bare (Afro). Fore wing of macropterous female with disc extensively brown to orangish but variably patterned by hyaline regions with white setae, including either a posteriorly tapered (Afro, Fig. 8 View FIGURES1–9 ) or anterior and posterior hyaline regions (Neo, Figs 16 View FIGURES 10–18 , 41 View FIGURES 37–45 , 52 View FIGURES 46–53 ) behind marginal vein. Fore wing of brachypterous female at most only slightly bent at junction of meso- and metasoma; venation with differentiated stv and pmv; with similar setal and colour patterns as macropterous females ( Figs 25 View FIGURES 19–27 , 53 View FIGURES 46–53 ) or hyaline regions without white setae ( Fig. 34 View FIGURES 28–36 ). Prepectus bare (e.g. Fig. 32 View FIGURES 28–36 ) or setose (e.g. Fig. 15 View FIGURES 10–18 ); often subdivided near mid-length by variably distinct vertical line. Mesopleurosternum with at least mostly white hairlike to slender-lanceolate translucent setae on mesopectus anterolaterally and usually acropleuron anteriorly (e.g. Fig. 15 View FIGURES 10–18 ), though often also with some dark hairlike setae dorsally below tegula (e.g. Fig. 23 View FIGURES 19–27 ). Middle leg with mesotibial apical groove, mesotibial apical pegs over base of tibial spur, and mesobasitarsus with single row of pegs ventrally along anterior and posterior margins. Hind leg sometimes with metafemur compressed, but posterior margin neither acutely angled nor linearly white. Propodeum with foramen ƞ-shaped incurved variably closely to v-like emarginate anterior margin such that plical region sometimes sublinear medially (Afro, Fig. 6 View FIGURES1–9 : plr), to over half length of scutellum (Neo, Figs 17 View FIGURES 10–18 , 26 View FIGURES 19–27 , 35 View FIGURES 28–36 , 45 View FIGURES 37–45 , 58 View FIGURES 54–59 : plr), but at least callar region (e.g. Figs 6 View FIGURES1–9 , 58 View FIGURES 54–59 : car) quite broad, convex, and with variably distinct oblique postspiracular groove (e.g. Figs 6 View FIGURES1–9 , 17 View FIGURES 10–18 , 26 View FIGURES 19–27 , 58 View FIGURES 54–59 : psg) extending from spiracle posteriorly to foramen at level of lateral margin of petiole, with the groove distinguishing variably coarsely sculptured medial region from smooth or at least less coarsely sculptured lateral region (Neo, Figs 17 View FIGURES 10–18 , 26 View FIGURES 19–27 , 35 View FIGURES 28–36 , 45 View FIGURES 37–45 , 58 View FIGURES 54–59 ) or more uniformly but distinctly sculptured callar region (Afro: Fig. 35 View FIGURES 28–36 ). Gaster ovate or sides diverging posteriorly to about level of cerci, but about as long as combined length of head and mesosoma; often entirely dark (e.g. Fig. 20 View FIGURES 19–27 ) but sometimes white dorsobasally (e.g. Fig. 48 View FIGURES 46–53 ) and/or ventrobasally (e.g. Figs 11 View FIGURES 10–18 , 50, 51 View FIGURES 46–53 ); posterior margin of tergites transverse or only shallowly emarginate; Gt1 smooth and shiny (Neo) to finely meshlike coriaceous (Afro, Fig. 6 View FIGURES1–9 ) and Gt2–Gt4 variably sculptured, but at least Gt6 and syntergum meshlike granular or reticulate to reticulate-rugulose; syntergum variably strongly transverse and long relative to Gt6, but with abruptly recurved, comparatively small, yellowish or paler syntergal flange contrasting with otherwise darker tergite; ovipositor sheaths yellowish and not or only just projecting beyond syntergal flange.

MALE. Unrecognized.

Discussion. When Gibson (1995) established Argaleostatus for Eupelmus testaceus he combined the Greek words argaleos (meaning ‘troublesome’ or ‘vexatious’) and statos (meaning ‘standing’) to reflect the uncertain relationships of the taxon with other eupelmines and the correct classification of its only included species. Gibson (1995, p. 149) stated that females of Argaleostatus were distinguished by a unique structure of their propodeum: “conspicuously large (median length about 0.6 length of scutellar-axillar complex), with median carina, and with oblique furrow between spiracle and foramen separating coriaceous-reticulate anteromedian region from smooth and shiny lateral region ” (my italics) ( Fig. 58 View FIGURES 54–59 : psg; Gibson 1995, figs 235, 236), in combination with their bidentate mandibles ( Fig. 47 View FIGURES 46–53 ), flanged syntergum ( Fig. 59 View FIGURES 54–59 ), and colour pattern ( Gibson 1995, p. 148: “head metallic green with bronze luster under certain angles; mesosoma and metasoma yellowish”) ( Figs 46–51 View FIGURES 46–53 ). However, similar structures of the mandibles ( Gibson 1995, table 1, character 1, state 2a) and syntergum ( Gibson 1995, table 1, character 39, state 3) are shared with females of several other genera, including those of the much more speciose genus Anastatus . Females of some Anastatus species, at least from the Neotropical region, including many that are brachypterous, also share a similarly green head that contrasts with a yellowish meso- and metasoma (personal observation). Gibson (1995) hypothesized that Argaleostatus formed a monophyletic group with Anastatus , Eueupelmus Girault , Taphronotus Gibson and, questionably, Paranastatus Masi based on Gt2 (Mt3) being hyaline and usually forming a part of a subbasal white band on the gaster ( Figs 48–51 View FIGURES 46–53 ). At that time females of the only two known species of Lutnes were characterized by an entirely dark gaster ( Figs 20 View FIGURES 19–27 , 38 View FIGURES 37–45 ). Gibson (1995) suggested that the distinctive features of Argaleostatus testaceus relative to typical Anastatus females were likely all secondary modifications correlated with brachyptery and that recognition of Argaleostatus could well render Anastatus paraphyletic. However, he recognized A. testaceus as a separate genus because by including it and/or the other above-listed genera in Anastatus would make morphological characterization of Anastatus so broad as to encompass most female eupelmines that are characterized in part by a syntergal flange ( Gibson 1995, fig. 519; character 39, state 3).

Gibson (1995, fig. 520) also suggested that Lutnes and Macreupelmus were sister taxa based on two shared features that were then hypothesized as synapomorphies—common possession of dark setae on the propleuron and prosternum (character 16, state 2), and fore wing disc with lanceolate or scale-like setae behind the marginal vein (character 33, state 2). However, both features were recorded for some members of some other genera ( Gibson 1995, table 1) so both are at least homoplastic. Females of several genera, including Argaleostatus , were recorded as having lanceolate setae behind the marginal vein. Further, the newly described species L. aurantimacula and L. infucatus show that colour of the propleural, prosternal and pronotal collar setae is variable in Lutnes , often being dark but sometimes white. Consequently, neither feature precludes classification of A. testaceus in Lutnes. Gibson (1995, p. 218) also described the propodeum of Lutnes as: “foramen incurved almost to apex of v-like emargination, but with short median carina ... callar region inclined from plical furrow, with oblique groove between spiracle and foramen, and sometimes much more distinctly coriaceous medially than posterolateral to groove ” (my italics) ( Fig. 26 View FIGURES 19–27 : psg; Gibson 1995, fig. 464). Thus, females of both A. testaceus and other Neotropical species that would be classified in Lutnes have a propodeum whose callar region is subdivided by an oblique postspiracular groove extending from the spiracle posteriorly to the foramen near the lateral margin of the petiole, which separates a variably more coarsely sculptured region mesal to the groove than lateral of the groove (e.g. Figs 17 View FIGURES 10–18 , 26 View FIGURES 19–27 , 58 View FIGURES 54–59 : psg). The holotype of L. afrotropicus has a similar propodeal sculptural pattern except the surface is more uniformly sculptured on either side of less distinct postspiracular groove ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES1–9 : psg). Females of A. testaceus are also similar to other species that would be classified in Lutnes in the other features given above in the generic description, or at least those species from the Neotropical region. For these reasons I consider Eupelmus testaceus Cameron and the other five species included in Lutnes to constitute a monophyletic group (see further below), and thus synonymize Argaleostatus under Lutnes n. syn. and transfer E. testaceus to Lutnes as L. testaceus (Cameron) n. comb.

Although the six species included in Lutnes may well constitute a monophyletic lineage, recognition of these as a separate genus from Anastatus could still render this latter taxon paraphyletic, as suggested by Gibson (1995) for Argaleostatus relative to Anastatus . Females of different species of Anastatus often have whitish-translucent, lanceolate setae on the lower half of the face. They usually also have very similar head and scrobal depression structures to the Neotropical species of Lutnes except that the carinate lateral margin of the scrobal depression curves ventrally toward and along the outer margin of the torulus ( Gibson 1995, fig. 15) rather than laterally toward the inner orbit as in Lutnes ( Gibson 1995, figs 13, 462), although this difference is more subtle for L. testaceus ( Gibson 1995, fig. 13). As noted above, female Anastatus characteristically have the gaster white ventro- and dorsobasally, but so does L. aurantimacula ( Fig. 11 View FIGURES 10–18 ) in addition to L. testaceus ( Figs 48–51 View FIGURES 46–53 ), and the gaster is at least white ventrobasally in L. infucatus ( Fig. 29 View FIGURES 28–36 ). Female Anastatus also often have variably infuscate fore wings with anterior and posterior hyaline regions with white setae behind the marginal vein similar to Lutnes females, though the orangish to dark brown discal setae of at least macropterous females of Anastatus typically are hairlike rather than lanceolate. However, the macropterous females of the Australasian species Anastatus picticornis (Cameron) and females of some brachypterous Anastatus species have comparatively dense and broad discal setae so that these more closely resemble the lanceolate setae of Lutnes species (personal observation). All the ‘typical’ morphological features that characterize Anastatus females are quite likely symplesiomorphic, except possibly for the basally white rather than uniformly dark gaster. However, this latter feature appears to be prone to homoplasy ( Gibson 1995, table 1, character 42, state 2), likely because of functional significance related to avoidance of predation ( Gibson 2017b). Perhaps most important for a hypothesis that Lutnes may render Anastatus paraphyletic is the characteristic propodeal structure of at least macropterous females of Anastatus , which includes a more or less “bowtie-like” shaped plical region. This bowtie-like appearance results from the foramen being ƞ-like incurved almost to a v-like emarginate anteromedial margin of the propodeum so that medially the plical region is sublinear with ×-like convergent margins. On either side of the median, variably concave, more or less triangular regions together differentiate a relatively narrow bowtie-like plical region relative to usually flat to somewhat concavely but distinctly inclined callar regions that slope up to the spiracle and then slope down lateral to the mesal margin of the spiracle ( Gibson 1995, figs 212, 247; Gibson et al. 2012, fig. 4). The line of curvature separating the inner and outer inclined callar surfaces is variably developed and in some species is evident as a relatively inconspicuous postspiracular line similar in placement to the postspiracular groove of Lutnes . However, both callar surfaces are characteristically quite smooth and shiny in Anastatus females, even if the inner inclined surface is sometimes slightly sculptured. Consequently, the propodeal structures of Lutnes females likely represent modifications in which the callar regions have secondarily become more uniformly convex on either side of a postspiracular groove and with either the region mesal to the postspiracular groove becoming noticeably more coarsely sculptured (Neo: Figs 17 View FIGURES 10–18 , 26 View FIGURES 19–27 , 35 View FIGURES 28–36 , 45 View FIGURES 37–45 , 58 View FIGURES 54–59 ) or the entire callar region becoming quite distinctly sculptured (Afro: Fig. 6 View FIGURES1–9 ), and the plical region (Neo) secondarily becoming longer medially than for typical macropterous Anastatus . The propodeum of the unique female of L. afrotropicus differs from Neotropical Lutnes because the foramen is only sublinearly separated from the anterior margin and there is a median bowtie-like plical region ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES1–9 : plr) more similar to typical Anastatus females. The propodeal features of Lutnes likely are apomorphic relative to those of typical macropterous Anastatus and, if so, Lutnes could well represent a lineage derived from some lineage within Anastatus , i.e. render it paraphyletic. Recognition of genera that render another more speciose genus such as Anastatus paraphyletic is arguably not an ideal classification. However, Gibson (1995, figs 517, 518) already noted that three cosmopolitan and speciose genera, Brasema Cameron , Zaischnopsis and Anastatus , may well constitute a nested (sequential) paraphyletic assemblage of such great morphological diversity that if the species were united into a single genus this could not be effectively characterized. Recognition of Lutnes simply adds to the potential assemblage of sequential paraphyly of Anastatus , as do possibly recognition of other small genera such as Eueupelmus Girault , Omeganastatus Gibson , and Taphronotus Gibson (Gibson 1995, fig. 519 ). Females of Lutnes can minimally be distinguished from those of Anastatus by their different propodeal structure/ sculpture patterns. The presence of lanceolate rather than hairlike setae on the fore wing disc is almost always also differential as is very often setose eyes. I therefore prefer to recognize Lutnes separate from Anastatus until such time as morphological and/or molecular evidence can more definitively resolve and substantiate species relationships among the genera discussed above.

Such features as black or white setae on the propleuron, prosternum and pronotum, and an entirely dark or basally partly white gaster in females of different species of Lutnes suggest these features are prone to homoplasy. Consequently, the groundplan states for the genus are not certain. However, if the nearest common ancestor is some Anastatus -like species, then dark prothoracic setae and an entirely dark gaster likely are secondary within Lutnes , even though the latter state is likely a groundplan feature of Eupelminae . It is also possible that females of the common ancestor of Lutnes were brachypterous rather than macropterous. This is based on the mesoscutum of included species, whether brachypterous or macropterous, being comparatively flat without distinctly differentiated, convex mesoscutal medial and lateral lobes and the dorsal surface of the pronotum being quite flat without a well differentiated collar and neck ( Figs 5 View FIGURES1–9 , 14 View FIGURES 10–18 , 22 View FIGURES 19–27 , 31 View FIGURES 28–36 , 42 View FIGURES 37–45 , 54, 55 View FIGURES 54–59 ). Macropterous females of Anastatus typically have more distinctly differentiated, convex mesoscutal medial and lateral lobes and a pronotum that is depressed mesally posterior to an anteriorly arcuate ridge that distinguishes the collar from the neck. A comparatively flat mesoscutum and pronotum similar to Lutnes females tend to be characteristic of females of brachypterous species of Anastatus ( Gibson 1995, figs 103–106) and those of many other genera ( Gibson 1995, figs 107, 108, 115, 121–132, 147–150). If so, females of L. testaceus are indicated to be morphologically most similar to those of the common ancestor of Lutnes except for their propodeal structure ( Fig. 58 View FIGURES 54–59 ), which is the longest of all Lutnes species. The propodeum of L. afrotropicus is more similar to that of typical Anastatus , as noted above. Interestingly, what I interpret as L. testaceus is polymorphic in wing development (though see Remarks under that species) and thus the only known species of Lutnes with both brachypterous and macropterous females. Wing polymorphism is also reported for females of some other eupelmine genera ( Gibson 2017a; Gibson & Fusu 2016), including three Palaearctic species of Anastatus : A. giraudi (Ruschka) [macropterous form described as A. dolichopterus by Bolívar y Pieltain (1934) (synonymy by Kalina 1981)], A. oscari (Ruthe) [brachypterous form described as Eupelmus micropterus Förster (1860) (synonymy by Ruschka 1921)], and A. bifasciatus (Fonscolombe) [brachypterous form described as A. gastropachae by Ashmead (1904b) (synonymy by Ishii 1938)1]. No Neotropical species of Anastatus is yet known to have both brachypterous and macropterous females, but the Neotropical species are poorly known and wing polymorphism may well exist unrecognized in this region as well.

The classification of L. afrotropicus in Lutnes represents the first record of the genus from outside of the Neotropical region and the only known female differs conspicuously in several respects from the Neotropical species, as noted above and in the generic description. In addition to its somewhat different propodeal structure and sculpture pattern, the head is conspicuously high-triangular with the frontovertex ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES1–9 : fvt) acutely angled relative to the face ( Fig. 4 View FIGURES1–9 : fa) at the level of the dorsal limit of the scrobal depression ( Fig. 3 View FIGURES1–9 ), which is wider than high and completely carinately margined between the inner orbits ( Figs 3, 5 View FIGURES1–9 ). The latter structure is quite obviously apomorphic compared to Neotropical Lutnes and Anastatus females. Also, the face has more slender, more hairlike white setae ( Figs 3, 4 View FIGURES1–9 ) compared to the broader, more lanceolate setae of Neotropical species (e.g. Figs 13 View FIGURES 10–18 , 40 View FIGURES 37–45 ), and in dorsal view there is a ridge-like ocellocular line between the anterior margin of the posterior ocellus and inner orbit. If the common ancestor of Lutnes was Anastatus -like in appearance then at least the more slender facial setae of L. afrotropicus likely also represents a secondary modification in this species, perhaps correlated with its different head structure. The L. afrotropicus female also has the costal cell bare dorsally, Gt1 quite distinctly though finely sculptured ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES1–9 ), and differs in antennal structure as well as somewhat in pro- and mesotibial structure. All except possibly the first of these features likely are secondarily derived as compared to typical Anastatus species, and all the features that distinguish L. afrotropicus from Neotropical Lutnes species could be secondarily derived. However, the carinate margins of the scrobal depression recurve laterally to the inner orbit, the eyes are setose, pronotal and mesoscutal structures are similar to those of the Neotropical species, and the fore wings have lanceolate setae behind the marginal vein. All these features suggest that L. afrotropicus is more closely related to other species classified in Lutnes rather than having derived the features independently from some common ancestor in Anastatus . For the present it seems better to classify L. afrotropicus in Lutnes rather than establishing one more monotypic genus in Eupelminae . Molecular evidence is necessary to test the hypothesis of relationships and classification.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Lutnes Cameron

| Gibson, Gary A. P. 2018 |

Lutnes

| Cameron, 1884 : 125 |

| Ashmead, 1904a : 289 |

| Girault, 1913 : 67 |

| Gibson, 1995 : 217 |

Argaleostatus

| Gibson, 1995 : 147 |