Balaenoptera borealis, Lesson, 1828

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6596011 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6596023 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/84551777-FF81-FFAD-FAD2-07FBFD2CF226 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Balaenoptera borealis |

| status |

|

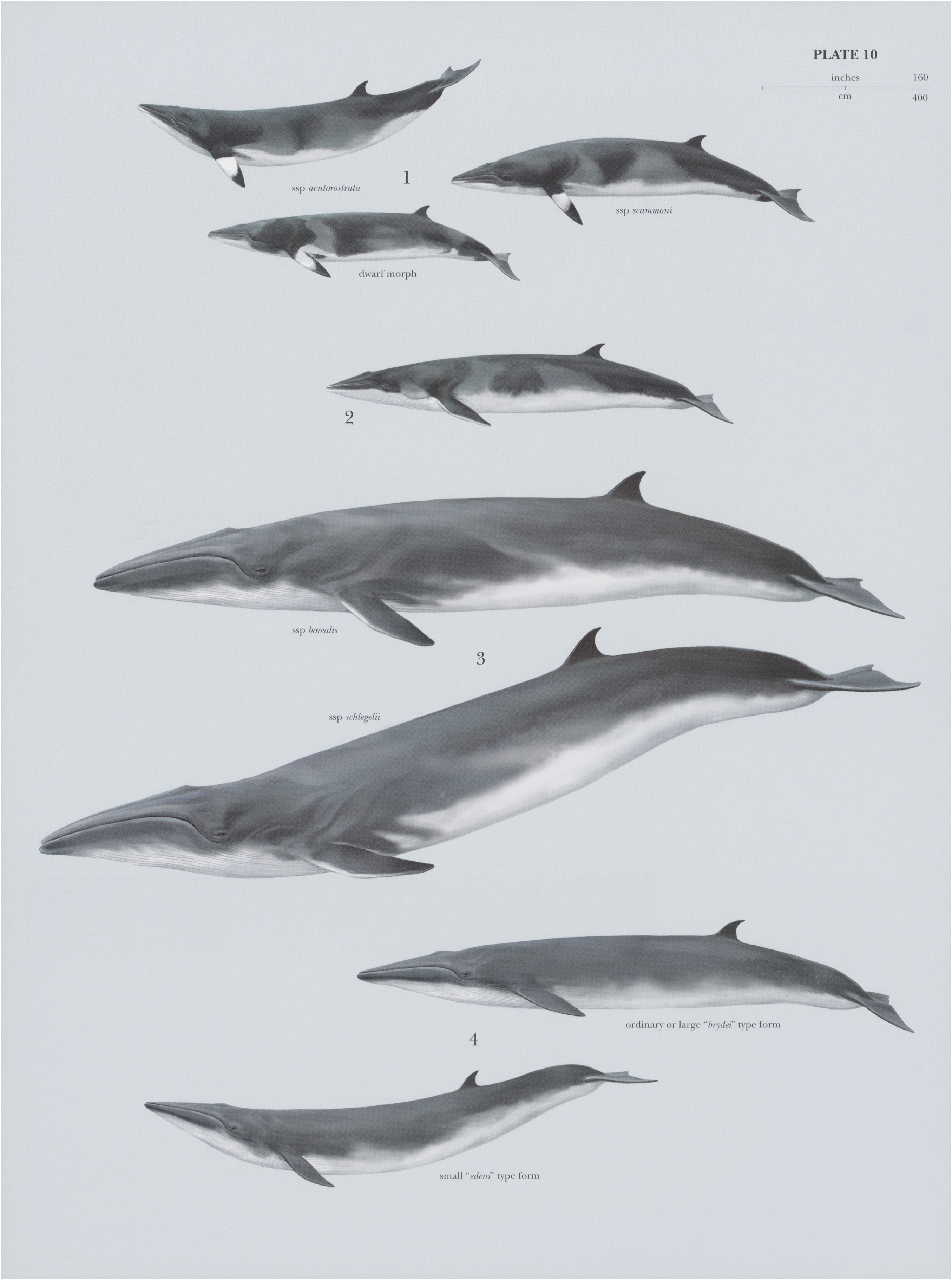

3. View Plate 10: Balaenopteridae

Sei Whale

Balaenoptera borealis View in CoL

French: Rorqual boréal / German: Seiwal / Spanish: Rorcual boreal

Other common names: Coalfish Whale, Northern Rorqual, Pollack Whale, Rudophi’s Rorqual; Northern Sei Whale ( borealis); Southern Sei Whale ( schlegelii)

Taxonomy. Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828 View in CoL ,

Germany, Schleswig-Holstein, Lubeck Bay, near Gromitz.

The type specimen stranded in 1819 on the coast of Schleswig-Holstein, in the Baltic Sea; this skeleton was in the Museum fur Naturkunde, Berlin, but Allied bombing during World War II destroyed it. Genetic and morphological support for recognition of a southern subspecies of B. borealis is relatively weak. Nevertheless, whaling records suggest a distinct size difference in the Southern Hemisphere and the Northern Hemisphere, with individuals from the Antarctic region typically larger than those from the North Atlantic Ocean. Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

B.b.borealisLesson,1828—oceansoftheNorthernHemisphere.

B. b. schlegelii Flower, 1865 — oceans of the Southern Hemisphere. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 1700-2000 cm; weight 22,000-38,000 kg. Total body length and weight estimates are 2000 cm and 38,000 kg in Antarctic waters, 1800 cm and 28,000 kg in the North Pacific Ocean, and 1700 cm and 22,000 kg in the North Atlantic Ocean. Adult female Sei Whales are slightly larger than males. Only an adult Blue Whale ( B. musculus ) and adult Fin Whale ( B. physalus ) are larger than an adult Sei Whale. The Sei Whale somewhat resembles a small-scale Fin Whale, although there are important differences. An adult Sei Whale generally is dark steel-gray on back, with bluish shade extending down flanks of body. In older individuals, there are lighter colored, gray-to-white, oval scars on body representing healed pits or bites caused by ectoparasitic copepods (Pennella spp.), lampreys (Petromyzon sp.), or cookiecutter sharks (Isistius brasiliensis). Ventral surface is slightly lighter than back with an irregular, grayish-white patch of variable size near ventral groove blubber. Undersides of pectoral flippers and caudal flukes generally are the same color as back, or slightly lighter. Lower lips are a uniform gray and lack coloration asymmetry of Fin Whales that have a gray left lip and a distinctly white right lip. Head ofthe Sei Whale is 21-25% of total body length. Dorsal surface of head is marked by a single, prominent, median rostral ridge that extends from blowholesto tip of snout. Forms in the Bryde’s Whale ( B. edeni ) complex—the nominate form and the “ brydei ” form—also have prominent median dorsal rostral ridges, but they have two additional and shorter, auxiliary rostral ridges, one on either side of median ridge. From above, lateral margins of rostrum of the Sei Whale are slightly convex, and thusits rostrum is intermediate in shape between the broadly U-shaped rostrum of the Blue Whale and the more sharply pointed rostrum of the Fin Whale. In lateral view, rostrum of the Sei Whale has a slight dorsally arched profile, especially prominent on anterior 25% of rostrum. This dorsal arching is reminiscent of the condition in balaenid and eschrichtiid mysticetes and is perhaps functionally related to the fact that the Sei Whale is known to practice a form of skim or ram feeding to supplement its normal rorqual-style lunge feeding. Dorsalfin of the Sei Whale is relatively tall (25-60 cm), strongly falcate in shape with a broadly convex dorsal margin and is positioned on the back slightly less than two-thirds the distance from tip of rostrum to flukes. Pectoralflipperis relatively small and slender, with a distinctly pointed apex, and measures ¢.9% of total body length. As with all species of rorquals, there are only four elongate digits in the flipper (digit I is lost). Caudal flukes of the Sei Whale are also relatively small (compared with the Fin Whale), width measuring only ¢.25% of total body length. Deep, median notches mark relatively straight, trailing edges of flukes. Ventral groove blubberis rather distinct and typically marked by 38-62 relatively short grooves that terminate well anterior to umbilicus, approximately midway between flippers and umbilicus. In most rorquals (except the Common Minke Whale, B. acutorostrata , and the Antarctic Minke Whale, B. bonaerensis ), ventral grooves extend to and often beyond umbilicus. Baleen apparatus of the Sei Whale consists of individual laminae that are relatively longer and narrower than in other rorquals, with an average length-to-width ratio typically greater than 2-2:1. Baleen laminae are also oriented more vertically in the mouth, in contrast to the more ventro-laterally oriented baleen laminae of other species of rorquals. Largest main baleen plates of the Sei Whale are ¢.80 cm in length. Individual plates also show less cross-sectional curvature and are more anteroposteriorly flattened. Fringing baleen bristles are distinctly finer (c.0-1 mm in diameter) than in other species of rorquals. In these features of general shape, vertical orientation, transverse curvature, and bristle diameter, baleen laminae of the Sei Whale can be thought of as intermediate between those of balaenids and other species of rorquals. This morphological similarity may be the result of evolutionary convergence because Sei Whales are the only rorquals known to practice a form of skim feeding. Baleen of the Sei Whale is generally dark gray and often has a yellowishbrown hue expressed as diffuse longitudinal streaks. Some anterior laminae show a pale whitish hue, but there is no marked asymmetry in baleen coloration as occurs in Fin Whales, Omura’s Whales ( B. omurai ), and Antarctic Minke Whales. Baleen laminae of the Sei Whale generally number ¢.350 laminae/side or rack, but there can be 219-402 laminae. The Sei Whale is the swiftest of the rorquals and is known to reach top swimming speeds of 55 km/h for short periods. At sea, blowhole and prominent dorsal fin are often visible at the same time when an individualis surfacing. Blow is tall and columnar to bushy and generally up to 3-4 m high. When diving, the Sei Whale rarely raisesits tail flukes above the water or arches its back;it tends to sink en masse as it descends below the ocean surface. The Sei Whale rarely, if ever, breaches.

Habitat. General preference for temperate waters, not venturing far into high polar seas. The Sei Whale has a cosmopolitan geographical distribution like most species of rorquals and is found in all ocean basins. Knowledge about habitat preferences of the Sei Whale is more limited than for many other species of rorquals, largely due to its more pelagic nature and irregular migration patterns compared with more inshore species that seasonally frequent continental shelf regions of the world’s oceans. Numerous reports comment on the occurrence of Sei Whales in waters coincident with the shelfsslope break. Studies of critical rorqual habitat in the eastern North Pacific Ocean found a correlation of distribution of Sei Whales with the shelfslope break and also with more offshore areas characterized by complex submarine topography associated with seamounts. In this region, prey abundance was apparently driven by oceanographic conditions that both increase primary productivity (greater nutrient supply) and concentrate zooplankton (fronts, eddies, and gyres).

Food and Feeding. Like all species of rorquals, the Sei Whale is a lunge filter feeder, feeding on dense concentrations of planktonic and nektonic animals, although seeming to prefer copepods and krill. It also uses a type of skim-feeding behavior in waters where prey densities are lower, especially when on winter breeding and birthing grounds. Skim feeding is the typical feeding strategy of the Bowhead Whale ( Balaena mysticetus) and right whales ( Eubalaena spp. ) and involves a variety of skeletal and soft anatomical adaptations, some of which occur in a rudimentary form in the Sei Whale—perhaps as a result of convergent evolution. These convergent features include a slightly, dorsally arched and attenuated rostrum; a relatively tall lower lip; and relatively narrow baleen laminae characterized by very fine baleen bristles. Perhaps because of their ability to perform both lunge and skim feeding, Sei Whales have a rather diverse diet for a rorqual, and although tending to prefer copepods, they are known to consume krill, amphipods, pelagic decapods, cephalopods, and even schooling fish. The few studies available on diets of Sei Whales suggest that they are essentially stenophagous during a given feeding period consuming, for example, only copepods at one time and krill at another time. These studies are largely based on whaling records, wherein stomach contents of butchered whales were analyzed and found to contain monospecific prey concentrations. In the North Atlantic Ocean, Sei Whales are reported to prefer pelagic crustaceans, especially copepods (Calanus sp.) in the late stage of their molting cycle when caloric contentis highest. In the Norwegian Sea, seasonal waxing and waning of copepod abundance seems to be a biological driver of abundance of Sei Whales in these waters, with copepod concentrations growing rapidly in March-April, reaching a maximum in May, followed by a brief decline in early summer and another increase in late summer, before a sharp decline in the late autumn and winter. In waters around Greenland, feeding Sei Whales primarily consumekrill (Meganyctiphanes spp. and Thysanoessa spp.), although schooling fish like sand lance (Ammaodytes tobianus), lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus), and capelin (Mallotus villosus) are also eaten. Sei Whales in the North Pacific Ocean also seem to prefer copepods (Calanus sp.), especially in waters around northern Japan, but they also feed on various species of krill (Fuphausia spp. and Thysannoessa spp.). Schooling fish also make up an important part of the diet of the Sei Whale in the Pacific Ocean and include anchovy (Engraulis spp.), sardines (Sardinops spp.), pollock (Theragra spp.), and capelin. Sei Whales appear to feed most actively between dusk and dawn, corresponding with diel vertical movement of prey species to near surface waters at night. Perhaps related to this is the observation that Sei Whales generally do not dive as deeply as other species of rorquals. Thus, modified skim-feeding behavior may represent an adaptation for feeding on prey that is less densely concentrated in the water column at night than during the day. Some studies suggest that prey preference of Sei Whales may be dependent on ocean-basin topography, such as high relief areas like seamounts where upwelling of nutrient-rich waters results in phytoplankton blooms that are later followed by mass spawning of zooplankton. Related to this is the observation that summer feeding grounds of Sei Whales seem to occur in areas associated with oceanic frontal systems (fronts, eddies, and upwelling systems). No accounts of cooperatively feeding Sei Whales have been reported.

Breeding. Information about reproduction of the Sei Whale is limited and primarily comes from whaling postmortem records, which suggest that females reach sexual maturity at an average age of eight years and typically a body length of 1310-1340 cm. Males appearto be sexually mature at the same age but at slightly smaller body lengths of 1200-1270 cm. Comparisons of reproductive status taken during years of heavy commercial exploitation (1930s through 1970s) suggests that age of sexual maturity has declined from c.11 years before 1935 to c.10 years by 1945, falling to modern levels by the 1970s. There is little detailed information on composition of breeding groups, although some data suggest that males dominate group structure on breeding grounds. Conception occurs in respective austral and boreal winters, with a peak in June-July in the Southern Hemisphere and in November—December in the Northern Hemisphere. Gestation is 10-11 months, with a single young born in respective austral and boreal winters. Young are ¢.450 cm in length and weigh ¢.780 kg at birth. Young are weaned at 6-8 months on summer feeding grounds when they are ¢.900 cm in length. This suggests an average neonatal growth rate of c¢.2 cm/day. Births in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean occur in February—March prior to northward migration to summer feeding grounds. Females reportedly reproduce on a two-year or even three-year cycle, suggesting an interbirth interval period of c.14-3 months. Sex ratio of neonates is essentially 1:1, and this probably holds for much of the year except for periods when differential segregation of sexes or sexual classes occurs on or at the ends of seasonal migrations. Studies of growth layers formed in wax plugs taken from external ear canals of dead Sei Whales suggest that they live up to 60 years.

Activity patterns. Limited information exists concerning daily activity patterns of Sei Whales. Acoustic studies, however, conducted in the Gulf of Maine in the western North Atlantic Ocean suggest a correlation between diurnal movements of copepods and rates of vocalization and feeding activity of Sei Whales. Nocturnal movement of copepods to near the sea surface was associated with decreased rates of vocalization in Sei Whales feeding at the same depth. Conversely, during the day when copepods had migrated into deeper water, vocalization of Sei Whales increased possibly due to increased social interactions and greater difficulty in locating prey. Like all species of rorquals, annual activity patterns of Sei Whales are primarily related to migration between summer feeding grounds and winter breeding, birthing, and nursery grounds.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Because of anti-tropical distribution and out-of-phase seasonal migration patterns of Sei Whales, northern and southern populations are seldom, if ever, sympatric. Complete allopatry would eliminate gene flow between the two regions, thus lending support to the recognition of separate northern and southern subspecies. Sei Whales in the North Pacific Ocean are distributed mainly north of 40° N during boreal summer, extending into the Gulf of Alaska and even the Bering Sea. During boreal winter in the North Pacific Ocean, Sei Whales are more widely dispersed, with some individuals known to winter in subtropical waters off the Bonin Islands (27° N) in the west and as far south as the Revillagigedo Islands (18° N) in the east. Probably because of whaling related mortality, the majority of Sei Whales in the North Pacific Ocean occur today east of 180° W. During summer in the North Atlantic Ocean, Sei Whales typically occur north of 44° N in the west and up to 70° N in the east. Their winter distribution is poorly known, but it is reported to extend to ¢.28° N in the west (reports of Sei Whales in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico may represent misidentifications of Bryde’s Whales) and off Mauritania in the east. In the Southern Hemisphere, Sei Whales occur throughout the Southern Ocean during summer feeding season, generally between 40° S and 50° S. Austral winter distribution of Southern Sei Whales is poorly known and primarily based on whaling catch records, which reported Sei Whales off north-eastern Brazil (7°S) in the western South Atlantic Ocean and off Angola (8° S) in the eastern South Atlantic Ocean. During austral spring migration, Sei Whales tend to arrive on feeding grounds after Blue Whales and Fin Whales have already been there and typically do not forage as far south as the latter species, remaining well north of the Antarctic pack ice. It is unknown, however,if all Sei Whales in the Southern Hemisphere actually make a full southern migration; some individuals may remain in more temperate waters as year-round residents. The pole-ward summer migration of Sei Whales in both hemispheres typically begins with pregnant females leaving breeding and birthing groundsfirst, followed by the remaining adult whales and then immature individuals. Densities are not well known and vary with time of year and geographical location. During austral and boreal winters when Sei Whales are in warmer waters, groups can consist of 2-5 mature individuals dominated by males. In contrast, migrating whales are often solitary, except for mother—offspring pairs. Solitary whales also occur on feeding grounds, although large groups of 20-100 individuals have been reported. Social structure of large groups is not well known, and associations may simply be passive and a function of prey abundance rather than actual social interaction. Whaling records suggest a 1:1 sex ratio in the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans, while males seem to outnumber females by 6:4 in Antarctic waters. Based on limited genetic data and vocalization patterns, it is assumed that discrete populations of Sei Whale inhabit each ocean basin, except perhaps for the Southern Ocean where several populations may occur. Although Sei Whales are the least acoustically known, they vocalize, like all species of rorquals, at infrasonic frequencies mainly below 1 kHz. In the Southern Ocean, Sei Whales produce broadband sounds described as growls and “whooshes™ (100-600 Hz, 1-5 seconds in duration), as well as low frequency tonal (100-40 Hz, lasting 1 second) and down-sweep calls (39-21 Hz lasting 1-3 seconds). The latter calls often have multiple parts, with a frequency step in between. Calls of Sei Whales recorded in the western North Atlantic Ocean off Cape Cod, USA, consist of down-sweep sounds (82-34 Hz, lasting 1-4 seconds) and are made as a single call. This vocalization pattern might represent a contact call that allows dispersed individual Sei Whales to coordinate activities such as feeding or breeding. Acoustic studies in the Gulf of Maine found a correlation between diel movement of copepods, rate of Sei Whale vocalization, and feeding behavior. Vocalization rates were lower at night when Sei Whales were feeding close to the surface on copepods that had moved from deeper in the water column. Conversely, during the day when copepods had returned to deeper water and feeding was more difficult, Sei Whales vocalized possibly due to increased social activity.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Causes of population decline of the Sei Whale are obvious and well documented in kill records kept by the whaling industry. Based on these data,it is estimated that the global population of mature individuals declined by ¢.80% in 1937-2007. Commercial whaling of the sleek and fast swimming Sei Whale did not begin until the advent of fast kill boats and explosive-tipped harpoons in the late 19" century. Preference of Sei Whales for offshore, pelagic waters also contributed to the delay in its commercial exploitation. Whalers initially preferred to hunt and kill larger rorqual species like the Blue Whale and the Fin Whale and only turned to hunting the Sei Whale when stocks of the other species eventually were depleted. By the 1880s, however, whalers were successfully hunting Sei Whales in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean, with more than 4000 whales reported killed in the Norwegian Sea and surrounding waters in 1885-1900. Hunting of Sei Whales began in Antarctic waters in the early 1900s and steadily increased until World War II. Between 1909 and 1938, it was estimated that 27,847 Sei Whales were killed worldwide. The majority of these whales were killed in northern ocean basins (12,909 individuals in the western North Pacific Ocean, 1019 individuals the eastern North Pacific Ocean, and 746 individuals in the North Atlantic Ocean), while just over 4500 individuals were killed in Antarctic waters. Commercial hunting of southern populations of Sei Whales, however, accelerated in the 1960s with more than 110,000 individuals killed in 1960-1970. Historical estimates of pre-whaling populations of Sei Whales suggested up to 42,000 individuals in the North Pacific Ocean and 60,000-65,000 individuals in the Southern Hemisphere. Pre-whaling population estimates of Sei Whales in the North Atlantic Ocean have not been calculated. Current population estimates suggest that Sei Whales have been largely extirpated from the eastern North Atlantic Ocean, while the population in the central North Atlantic Ocean may number as many as 10,300 individuals. No recent population estimates are available for Sei Whales in the western North Atlantic Ocean, although ship-based surveys in the late 1960s put the population at ¢.2080 individuals. Estimates of populations of Sei Whales in the North Pacific Ocean are also relatively low, with fewer than 8600 individuals estimated in 1974. This low number reflects conditions following an 11year period (1963-1974) of intense exploitation during which ¢.40,000 Sei Whales were killed. Although there are no estimates for populations of Sei Whales in the Southern Hemisphere more recent than 1979, most workers place the current population at 9800-12,000 individuals. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) established a moratorium on killing Sei Whales in the North Pacific Ocean in 1975. Similar moratoria were established in 1979 and 1986 for populations in the Southern Hemisphere and North Atlantic Ocean, respectively. Current threats to Sei Whales include ship strikes, entanglement in lost fishing gear (bycatch), and renewed whaling of North Pacific stocks (100 ind/year) by Japan under special “scientific permits.” Calculations based on estimates of natural mortality rates, age at first reproduction, and annual pregnancy rates suggest an average increase of only 2:7% /year for the global population of the Sei Whale.

Bibliography. Baumgartner & Fratantoni (2008), Brodie & Vikingsson (2009), Gambell (1985a), Horwood (1987, 2009), IWC (1977), Prieto et al. (2012), Reilly et al. (2008c).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

SubOrder |

Mysticeti |

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Balaenoptera borealis

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2014 |

Balaenoptera borealis

| Lesson 1828 |