Intasuchus silvicola

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.37520/fi.2020.019 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/6B5B87F8-CE23-FFFD-83C1-FEC918EFFDF1 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Intasuchus silvicola |

| status |

|

Intasuchus silvicola KONZHUKOVA, 1956

Text-figs 12 View Text-fig , 13 View Text-fig

H o l o t y p e. PIN 570/1, housed in Paleontological

Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia.

T y p e h o r i z o n. Intinskian Formation.

A g e. Ufimian, late Kungurian (273–274 Ma, after

Schneider et al. 2020), Cisuralian, lower Permian.

T y p e l o c a l i t y. Coal mine near ‘Greater Inta River’,

Komi Republic, northeastern European Russia.

E m e n d e d d i a g n o s i s. Unique characters among stereospondylomorphs:

(1) Lacrimal very elongated and longer than the nasal.

(2) Parietal and supratemporal relatively short and wide.

Characters in contrast to specific stereospondylomorph species, but shared with others:

(3) Elongated alary process of the premaxilla reaching posteriorly to a level in the middle region of the septomaxilla (similar in Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.).

(4) Anteriorly wide and blunt prefrontal, reaching anteriorly a level in the anterior region of the frontal (shared with late adult C. vranyi ).

(5) Posteriorly narrow squamosal, but not going beyond the posterior region of the tabular (similar in Korkonterpeton kalnense sp. nov. and C. vranyi ).

(6) Very short tabular (shared with Glanochthon ).

(7) Tabular – supratemporal suture lying at the level of the posteromedian margin of the skull table (as in G. angusta ).

(8) Elongated postparietal (shared with Glanochthon and Cheliderpeton ).

(9) Slightly concave posterior skull margin (as in C. vranyi ).

(10) Palatine with two pairs of fangs – the largest teeth of dentition (shared with Glanochthon ).

(11) Anterior palatine ramus of the pterygoid medially curved (shared with Archegosaurus and Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.).

(12) Anterior tip of the parasphenoid cultriform process reaching the level of the anterior region of the pterygoid (shared with Archegosaurus and Korkonterpeton kalnense sp. nov.).

(13) Basipterygoid process of the basal plate large, anterolaterally directed and long sutured with the basipterygoid process of the pterygoid (similar as in Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.).

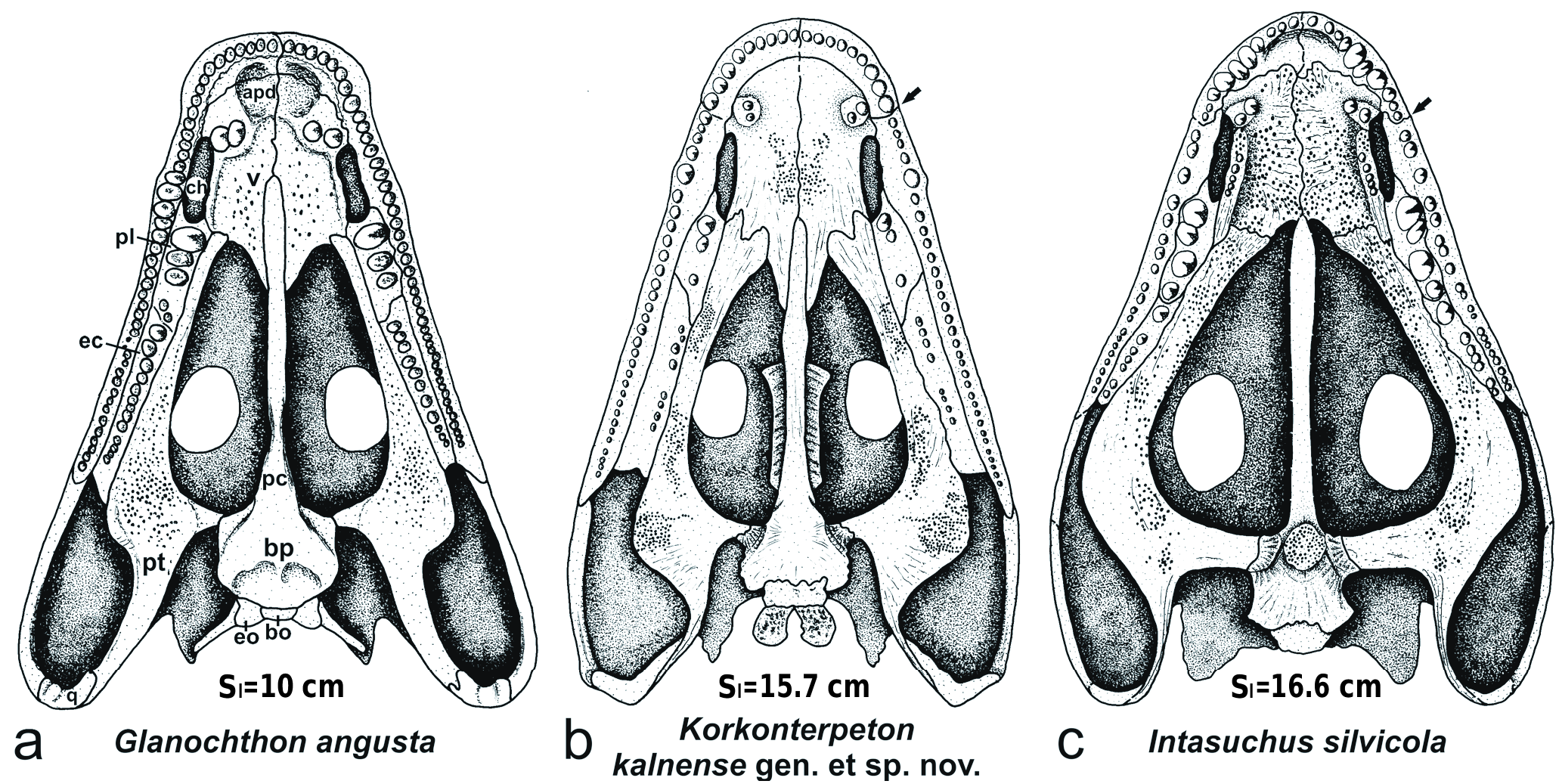

C o m p a r a t i v e d e s c r i p t i o n. General morphology. The holotype represeneted by the skull of Intasuchus silvicola KONZHUKOVA, 1956 is well preserved in dorsal and palatal views ( Text-fig. 13 View Text-fig ), only the posterolateral cheek and the quadrate region are missing. The skull has a midline length of 16.6 cm. The dermal ornamentation of the skull roof is exquisitely preserved: it consists of a dense pattern of central polygons and radial ridges on the margin of the bones. Together with the strong degree of ossification, this well-developed ornamentation pattern suggests an adult stage for this specimen ( Steyer 2000b). The natural relief of the skull roof is also well preserved.

The new cranial reconstruction of Intasuchus proposed here ( Text-fig. 12c, d View Text-fig ) is very different from those of Konzhukova (1956) and Gubin (1984) which are incorrect because both authors used the specimen No. PIN 570/2 ( Syndyodosuchus ) for the posterior region and did not take into account the enormous width of the jugal.

Skull roof ( Text-figs 12a, c View Text-fig , 13a View Text-fig , 14 View Text-fig , Tab. 1). The skull has an extremely elongated preorbital region measuring 2.35 times the length of the postorbital region ( Tab. 1: POl/Hl = 2.35; POl/Sl = 0.57). This postorbital region is indeed short (Hl/Sl = 0.24). The premaxillary snout region is narrow and pointed (aSw/Sl = 0.31). The premaxilla is moderately elongated, 1.4 times longer than the narial length. These two last characters are also seen in Cheliderpeton vranyi ( Werneburg and Steyer 2002) , but not in Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov., Glanochthon ( Schoch and Witzmann 2009b) and Sclerocephalus ( Boy 1988, Schoch and Witzmann 2009a). The distance between the nostrils is very short (INw/Sl = 0.14) and smaller than the intraorbital distance (IOw/Sl = 0.18; in contrast to most other stereospondylomorphs, and only shared with Archegosaurus ). The alary process of the premaxilla is elongated and posteriorly reaches a level in the middle region of the septomaxilla. The dorsal septomaxilla is relatively small but may be continued ventrally. Its posterior extremity is posterolaterally directed, in contrast to Glanochthon . The maxilla is slightly concave laterally, as is the case in Glanochthon ( Schoch and Witzmann 2009b) . It is dorsally relatively short and not in contact with the quadratojugal in dorsal view. The maxilla has no contact with the nasal, because the lacrimal enters the septomaxilla. The lacrimal is a very elongated and relatively wide. These two last characters are rarely seen in stereospondylomorphs except in the late adult C. vranyi . The nasal is narrow (in contrast to Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.). The intraorbital region (IOw/Sl = 0.18) and the frontals are also narrow. The orbit is large in size (Ol/Sl = 0.19) and elongate in shape; it is the most elongated orbit within stereospondylomorphs (similar only in Archegosaurus ). The postorbital region is short (Hl/Sl = 0.24), in contrast to C. vranyi . The prefrontal is anteriorly wide and blunt, and it reaches the level of the anterior part of the frontal (shared with the late adult C. vranyi ). The posterior process of the prefrontal and the anterior process of the postfrontal are wide, much wider than in the previous reconstructions by Konzhukova (1956) and Gubin (1984). The postfrontal is in clear contact with the prefrontal. The posterior part of the postfrontal is extremely elongated and reaches a level significantly posterior to the pineal foramen. This posterior process of the postfrontal forms an embayment in the anteromedial part of the supratemporal. These two last characters are unique in stereospondylomorphs. The postorbital is wide (Pow/Pol = 0.91) and relatively short. The jugal is anteriorly and especially posteriorly very wide (Jw/Sl = 0.16), in contrast to all other stereospondylomorphs. Therefore, the maximal width of the skull is at the level of the pineal foramen and the anterior part of the quadratojugal (mSw = 0.73), as in Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov. At this level, the posterolateral region of the jugal and the anterolateral region of the quadratojugal are missing, but it is possible to reconstruct the width of the skull according to the well-preserved palatal bones ( Text-fig. 12b View Text-fig ): the posteriormost margin of the skull probably runs medially to the posterolateral region of the quadratojugal. The posterior margin of the quadratojugal and the quadrate are not preserved. The squamosal is posteriorly narrow and does not extend posteriorly further than the posterior region of the tabular (in contrast to Glanochthon ). The ‘otic notch’ (squamosal embayment) is very deep and wide. The short suture between the squamosal and the supratemporal starts posteriorly at midlength of the supratemporal (in contrast to Glanochthon and Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov., but similar in the late adult C. vranyi ). The jaw joints are clearly posterior to the occiput. The parietal and supratemporal are relatively short and wide, in contrast to all other stereospondylomorphs. The anterolateral region of the parietal and the anteromedial region of the supratemporal present embayments for the large posterior region of the postfrontal. The tabular is very short, in contrast to Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov. The suture between the tabular and supratemporal lies at the same level as the occipital margin of the skull, as in G. angusta .The postparietal is elongated (in contrast to Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.) and laterally expanded in an embayment of the posteromedian part of the supratemporal (in contrast to all other stereospondylomorphs). The posterior skull margin is slightly concave because of the short distance between the posterior extremity of the tabular corner and the occipital midline margin (Thl/Sl = 0.06; as in C. vranyi ).

The natural relief of the dorsal skull roof is very well preserved ( Text-figs 12a, c View Text-fig , 13a View Text-fig ) and shows several ridges: the longitudinal ridge (prr) starts just below the posterior part of the alary process of the premaxilla, and runs along the anterior orbital margin of the prefrontal where it becomes progressively wider. It continues around the medial orbital margin of the pre- and postfrontal and becomes the intraorbital ridge (ior) up to the anterolateral end of the postorbital. The postorbital-tabular ridge (ptr) runs from the postorbital along the lateral margin of the supratemporal up to the tabular horn. At mid-length of the supratemporal, it becomes the parietalsupratemporal ridge (psr) which runs to the pineal foramen. Additionally, a curved lacrimal ridge (lr) lies on the anterior part of the lacrimal. This pattern of dorsal ridges looks similar to that of the eryopids but here it is less complex, especially on the postorbital region ( Sawin 1941, Werneburg 2007: figs 2a, 6, 7). A few transverse ridges between the longitudinal ridges are also missing on the preorbital region of Intasuchus and stereospondylomorphs in general. In eryopids, the lacrimal ridge runs more longitudinally and diagonally across the whole lacrimal. An elongated longitudinal ridge from the nasal up to the tabular (without transverse ridges) is known in Glanochthon latirostris ( Schoch and Witzmann 2009b: fig. 4B), Archegosaurus decheni (Witzmann 2006: figs 4a, 5a) and the archegosaur Collidosuchus tchudinovi ( Gubin 1991: fig. 1a).

Lateral line sulci are only impressed on the pre- and postfrontals. They are part of the supraorbital sulcus which is deeply marked.

Palate ( Text-figs 12b, d View Text-fig , 13b View Text-fig , 15 View Text-fig ). Most of the palatal bones are preserved as well as the dentition. The premaxilla bears ten teeth; the first three and the last two are small, but numbers 5–8 are almost as large as the palatine fangs. The maxillary bears about 25 teeth; the anterior ones are middlesized and the posterior ones smaller. No maxillary teeth are enlarged. The ventral side of the maxilla is medially enlarged next to the choana, which is similar to that of Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.

The vomer is narrow and elongated. A diagonally arranged pair of fangs, the size of the premaxillar middlesized teeth, is visible near the anteromedian margin of the choana. This correlates with the ventral premaxilla-maxilla suture in the posterior end of the choana. These two last characters are also seen in the other stereospondylomorphs but not in Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov. The vomer and the pterygoid are covered with numerous small denticles. The concave posterior margin of both vomers borders a very narrow part of the interpterygoid vacuities. In Intasuchus , the posterior process of the vomer is not developed, contra many other stereospondylomorphs. It is not clear if the anterior palatal depressions are present. A parachoanal vomerine tooth row is located on an elevation parallel to the medial choana: it contains five teeth the same size as the small premaxillary and maxillary teeth and small denticles anteriorly. A parachoanal vomerine tooth row is missing in Sclerocephalus , Glanochthon and Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov., but well known in Archegosaurus decheni (Witzmann 2006).

The choana is very narrow and elongated. The length of this slit-like opening is twice that of the nostril, as is the case in several stereospondylomorphs but not in Sclerocephalus where it is wider, and not in Archegosaurus where it is longer.

The ectopterygoid, of similar length as the palatine, reaches posteriorly the level of the anterior half of the orbit. In all other sterospondylomorphs this bone is longer and clearly extends posteriorly behind the orbit. The ectopterygoid has 8–9 teeth. The first and probably second (missing) teeth are large fangs the same size as the largest premaxillary teeth, only the palatine fangs are larger. The other posterior teeth on the ectopterygoid are small, but larger than the laterally neighbouring posterior maxillary teeth. The shape and dentition of the ectopterygoid is more similar to that of Sclerocephalus than to Glanochthon or Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.

The palatine is more elongated than the choana and has space for 4 very large teeth. It bears two pairs of fangs which are the largest teeth in the skull. The palatine dentition is comparable with that of Glanochthon , but differs from Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.

The pterygoid may have a very elongated basipterygoid ramus in contrast to all other stereospondylomorphs. This elongation of the basipterygoid ramus is putative, it is based on the median suture of the skull between the vomers in an approximately natural position to the maxillary tooth arcade as an indication of the natural margin of the skull. The quadrate ramus is only partly preserved. The palatine ramus is curved medially and has a broad anterior part, which reaches about two-thirds of the vomer width (in contrast to Glanochthon , but similar in Sclerocephalus and Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov.). The suture between the vomer and the pterygoid is very elongated. The anterolateral palatine ramus clearly ends posteriorly to the choana (in contrast to Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov., but known from Glanochthon ).

The parasphenoid has a narrow basal plate. The probably narrow cultriform process only contacts the posteromedian part of the vomer (i.e., no embayment of the vomer is visible). Both characters contrast with Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov., Glanochthon and Sclerocephalus . The anterior tip of the cultriform process reaches the level of the anterior pterygoid posteriorly to the choana, in contrast to Sclerocephalus , Glanochthon and Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov. The large basipterygoid process of the basal plate is anterolaterally directed and long sutured with the basipterygoid process of the pterygoid (similar in Korkonterpeton kalnense gen. et sp. nov., but different in Glanochthon and Sclerocephalus ). A fine groove for the carotid artery runs almost parallel to the medial margin of the basipterygoid process of the basal plate. The basal plate has an oval elevated patch covered by a denticle field between the basipterygoid processes. The narrow shape of the basal plate together with the denticle field is known from Archegosaurus decheni (Witzmann 2006) and the archegosaurid Platyoposaurus stuckenbergi ( Konzhukova 1955). The dorsal region of the basal part of the cultriform process appears through the left orbit in the specimen as preserved ( Text-figs 12a View Text-fig , 13a View Text-fig ). The fossa hypophysialis and three foramina are visible. The pair of outstanding ones may be for the anterior arteria carotis cerebralis (compare Gubin 1991: figs 13, 14).

The interpterygoid vacuity is posterolaterally very wide (in contrast to all stereospondylomorphs). The subtemporal fenestra is relatively narrow and anteriorly elongated (compare with the length of the ectopterygoid).

Braincase ( Text-figs 12b, d View Text-fig , 13b View Text-fig ). The ventral basioccipital is sutured anteriorly with the basal plate of the parasphenoid. The exoccipital and quadrate are not preserved.

Visceral skeleton ( Text-figs 12b View Text-fig , 13b View Text-fig ). The stapes has a wide footplate and a short preserved, slender shaft. The quadrate process is not visible. The basibranchial is not preserved.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.