Inachoididae, Drach & Guinot, 1983

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4766.1.5 |

|

publication LSID |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:0E43BB66-03FD-443E-9D6E-1BEE52B0C459 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3803769 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/663987C6-FFA0-A604-B6A0-FBB4FA82FF43 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Inachoididae |

| status |

|

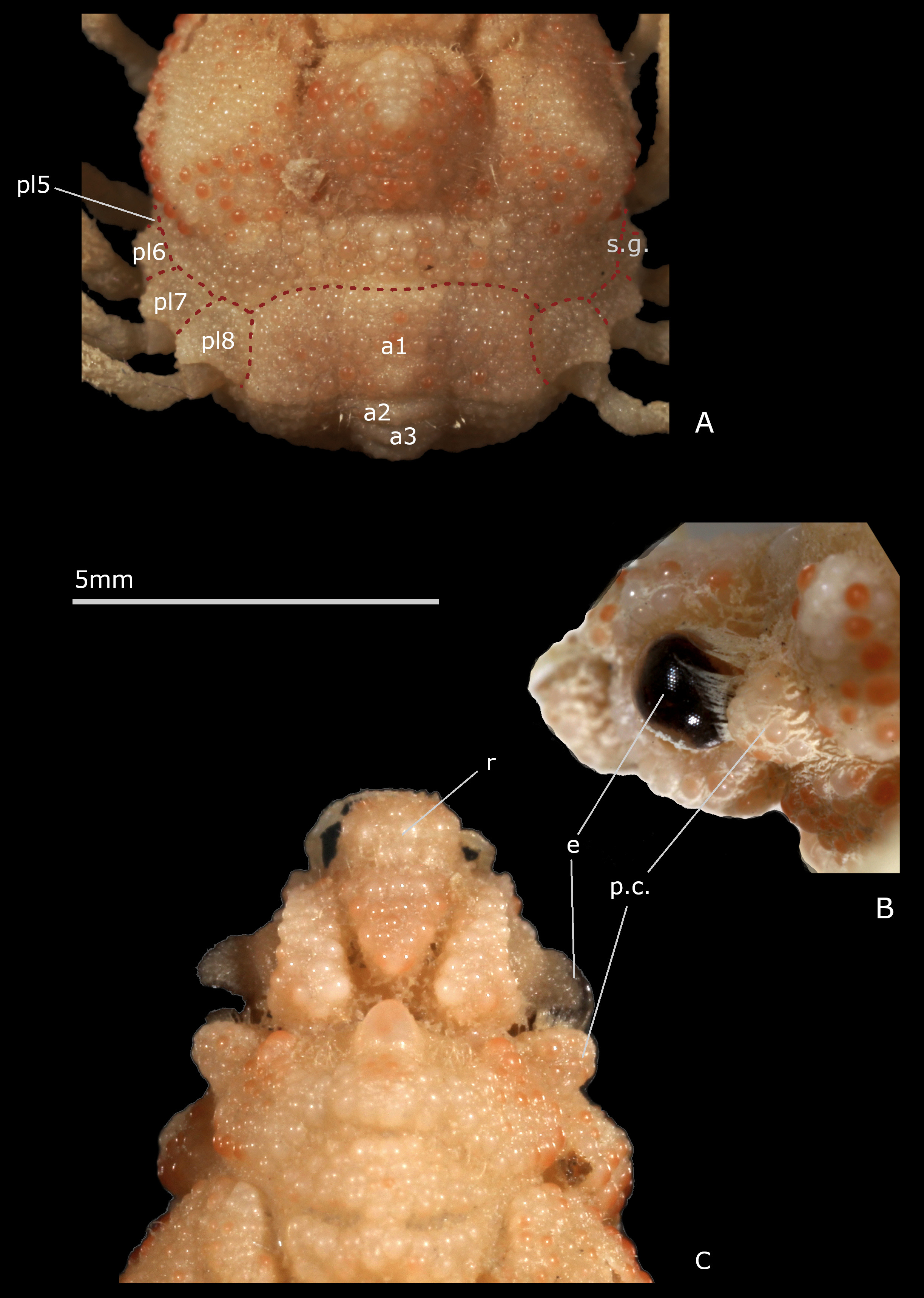

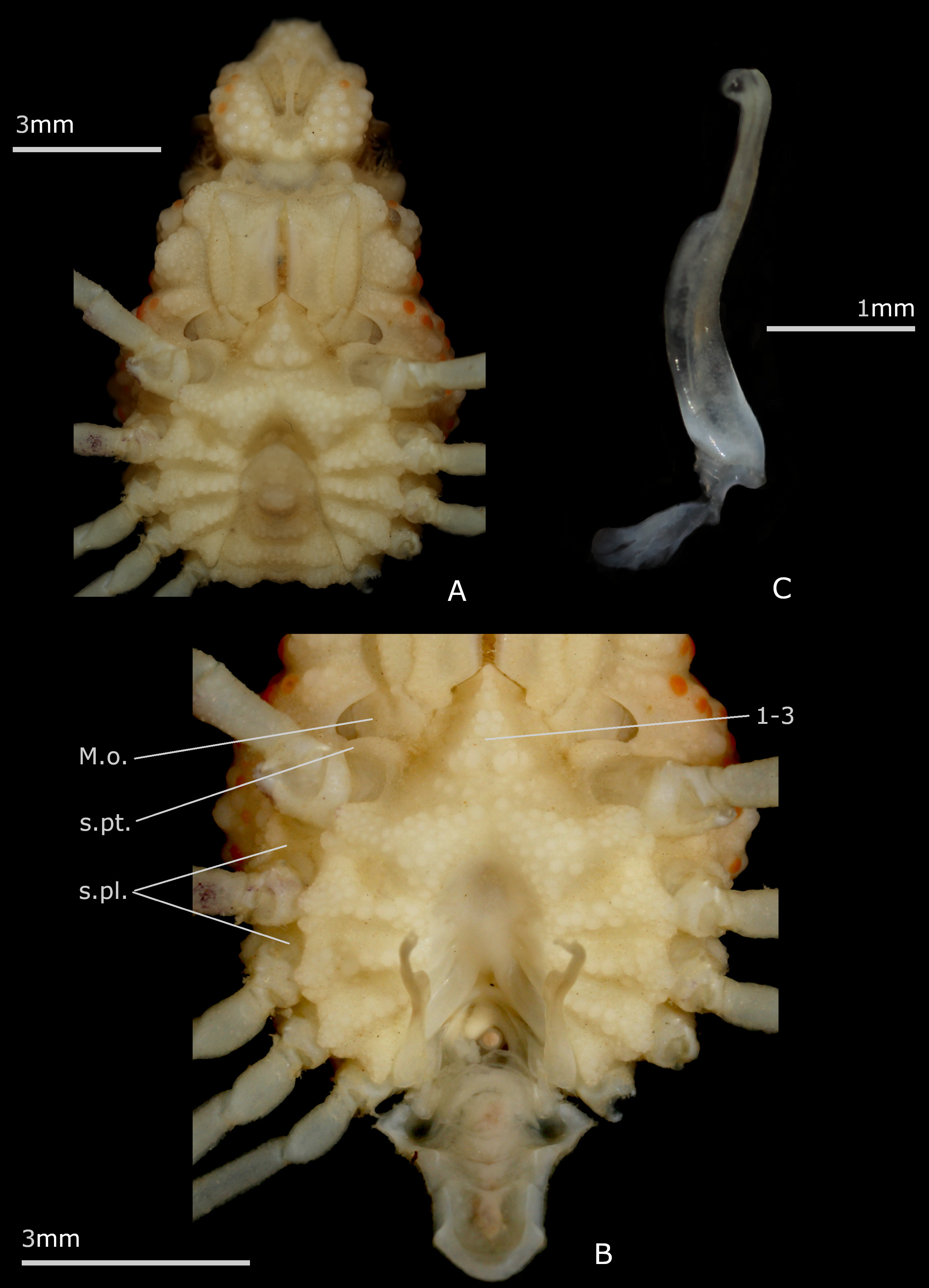

family Inachoididae View in CoL

A series of unambiguous synapomorphies support the family Inachoididae . The main inachoidid features are: exposure of the latero-external portions of pleurites 5–8 that, usually calcified and ornamented like dorsal surface, extend beyond each side of carapace. These external sclerites form a kind of collar all around the posterolateral margins of the carapace (irregular, however in Stenorhynchus Lamarck, 1818 ); this collar comprising, in addition, the wide and dorsal first (male or female) pleonal somite also incorporated into the carapace (thus appearing as part of the carapace) ( Drach & Guinot 1982: pl. 1, figs. 1–6; 1983: pl. 1, figs. 1–8); carapace setting in a gutter (except for Stenorhynchus ); absence of a true branchiostegite posterior to P2, i.e. carapace without lateral-ventral folding and not covering the insertion area of the pereiopods; thoracic sternum/pterygostome junction at sternite 4 level varying from absent ( Leurocyclus , Paradasygyius ) to complete ( Esopus , Paulita ), with intermediate states ( Collodes sensu lato, Inachoides ); sternal extensions between pereiopods, from P1 to P4, usually present; thoracic sternum broad; thoracic sternal suture 3/4 usually short, only lateral but deep, and often ending as a perforation of the sternal surface; sutures 4/5 to 7/8 interrupted, with distant interruption points, displaying pattern 5, subpattern 5e ( Guinot et al. 2013: fig. 50C, E); male pleon with all somites free except for somite 6 that is fused with telson (pleotelson); male gonopore opening far from suture 7/8, in a posteriormost location ( Guinot et al. 2013: figs. 31C, D, 50C, E); condylar protection of penis within the P5 coxo-sternal condyle, the penis emerging from the condyle’s extremity as e.g. in Stenorhynchus or from its anterior border as e.g. in Leurocyclus , Paulita and Esopus ( Guinot et al. 2013: 87, fig. 31C, D, table 4), this character needing to be checked in other genera; male pleon with deep sockets on pleotelson ( Guinot et al. 2013: fig. 50D, F), corresponding to prominent buttons on sternite 5; female pleon having a maximum of six elements, the somites 5 and 6 being fused to the telson (pleotelson); in adult females, formation of a large, discoid pleonal plate and development of a brood cavity limited by a high sternal ridge, closed like a box, the pleonal margin being tightly joined to its edge, thus the need of a branchiosternal canal for oxygenation of eggs ( Drach & Guinot 1982; 1983: pl. 1, figs. 7, 9; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: figs. 11E, 12E, F); pleurites regularly connected medially and with marked dorso-ventral partition due to developed junction plate; sternite 8 with basal bridge ( Leurocyclus ), median line absent ( Esopus ), or only basal ( Paulita ) or extending along thoracic sternite 8 ( Leurocyclus ); in females, forward orientation of sternite 6 leading to anterior displacement of vulvae ( Guinot et al. 2013: fig. 48A). It appears that many inachoidids do not possess hooked setae or show only sparsely distributed hooked setae (near the rostrum), at least when adults, and thus do not decorate ( Guinot & Wicksten 2015).

Depending on the extension of sternite 4, different states of the thoracic sternum/pterygostome junction are found in Inachoididae , resulting in diverse shapes of the Milne-Edwards openings and mxp3 coxae. The junction is absent in e.g. Paradasygyius depressus , Collodes leptocheles Rathbun, 1894 , Pyromaia tuberculata (Lockington, 1876) , and Leurocyclus tuberculosus (H. Milne Edwards & Lucas, 1842) , whereas it is complete, with entirely separated Milne-Edwards openings, in other species, e.g. Esopus crassus ( Fig. 4A, B View FIGURE 4 ), Paulita tuberculata , Batrachonotus fragosus Stimpson , and Euprognatha rastellifera Stimpson, 1871 , E. bifida Rathbun, 1893 ( Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: 488, figs. 11C, 12C, D, 13A, B, 14A, B; Guinot 2012; Guinot et al. 2013: figs. 48A, 49C, E).

Dissections have shown that the axial skeleton, with the pleurites almost horizontal and regularly connecting medially, was fused to the carapace by pillars, at least in Paradasygius depressus , Paulita tuberculata and Leurocyclus tuberculosus ( Drach & Guinot 1982: pl. 1, figs. 5, 6, as Paradasygius tuberculatus ; 1983: pl. 1, figs. 4, 7, 8; Guinot et al. 2013: fig. 47G–I), so that it is difficult to detach them from the carapace without breaking it. This exceptional connection, observed in inachoidids with a flattened carapace but also in those with a thicker body (e.g., Anasimus A. Milne-Edwards, 1880 , Collodes Stimpson, 1860 , at least pro parte), needs to be checked by dissection in all genera of Inachoididae . The exposure of the latero-external portions of pleurites 5–8 is a unique disposition that is found in all the inachoidid taxa. It should be noted, however, that the Raninoidea De Haan, 1839 (Gymnopleura Bourne, 1922) display a partial exposure of the pleurites 5–7, with heavily calcified exposed external portions, and by forming a somewhat excavated and roughly quadrilateral area between the pereiopod coxae and the branchiostegite ( Van Bakel et al. 2012).

The family Inachoididae includes the ten genera cited by Ng et al. (2008: 115) plus Erileptus Rathbun, 1893 , and three additional genera: 1) Paulita , established for Paradasygyius tuberculatus , distinguished from Paradasygyius depressus ( Guinot 2012) ; 2) Stenorhynchus , known by four species, traditionally assigned to the Inachidae , and transferred to the Inachoididae as a distinct subfamily, the Stenorhynchinae ( Guinot 2012) ; 3) Esopus , in the present paper (see also Guinot 2019).

The Inachoididae is mostly a New World family, formerly known exclusively from the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the Americas. But, with the addition of the genus Stenorhynchus , previously assigned to Inachidae and known by three American members plus a West-African species, S. lanceolatus (Brullé, 1837) , the distribution of the family now includes the eastern Atlantic (Madeira, Canary Is., Cape Verde Is., and numerous west-African localities from Western Sahara to Angola). Another exception is the invasive species Pyromaia tuberculata , now successfully established in several distant regions, see Galil et al. (2011).

The monophyly of Inachoididae has been recovered by an outstanding morphological cladistic analysis ( Santana 2008: 221). In a re-evaluation of larval support for the monophyly of majoid families ( Marques & Pohle 2003), Inachidae + Inachoididae (except Macrocheira ) formed a monophyletic clade in unconstrained analyses, with Leurocyclus nesting as the most basal taxon of Inachidae + Inachoididae , and Inachidae being a more derived group. Larval data, however, have not provided clear synapomorphies for Inachoididae , not supporting its separation from Inachidae ( Pohle & Marques 2000; Marques & Pohle 1998, 2003). According to Santana & Marques (2009: 55), all inachoidids with a completely described larval development ( Anasimus latus , Pyromaia tuberculata , Paradasygyius depressus ) conform for the most part to the general pattern of Majoidea (two zoeal stages), Leurocyclus differing, however, from the other inachoidids by several features and from all majoids by the setal formula of the distal article of the mxp2 endopod in both zoeal stages. The larval development of Paulita tuberculata , still unknown, is predicted to be peculiar, distinctive. Currently, the Inachoididae is recognised as a valid family on the basis of morphological criteria ( Melo 1996, as Inachoidinae ; Coelho 2006; Ng et al. 2008; Santana 2008; Guinot 2012; Guinot et al. 2013; Davie et al. 2015a, b, c; Antunes et al. 2016, 2018; Carmona-Suárez & Poupin 2016), also supported by molecular data ( Colavite et al. 2019), and phylogenomic analyses ( Wolfe et al. 2019), as well by paleontological data ( Artal et al. 2012, 2014; Jagt et al. 2015).

Inachoidids have a determinate growth, i.e. at sexual maturity they cease growing in favour of reproduction ( MacLay 2015: table 4).

The similarities between Inachoididae and Hymenosomatoidea MacLeay, 1838, and also with Dorippoidea MacLeay, 1838, were being interpreted as a synapomorphy relation by Guinot & Richer de Forges (1997), Guinot (2011b) and Guinot et al. (2013). The gutter inside which the carapace lies and involving pleurites 5–7 in Dorippoidea ( Guinot et al. 2013: figs. 46A, B, 47A, B) and the gutter involving pleurites 5–8 in Inachoididae ( Figs. 1 View FIGURE 1 , 2A View FIGURE 2 ) are both reminiscent of the rim that entirely or partly encircles the hymenosomatid carapace dorsal surface.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |