Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai & Türkay, 2012

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4057.2.7 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:84A1588A-351D-4978-B929-A6D02D113BDD |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6096550 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5C0087BA-537C-FFC0-FF7E-692A85868090 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai & Türkay, 2012 |

| status |

|

Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai & Türkay, 2012

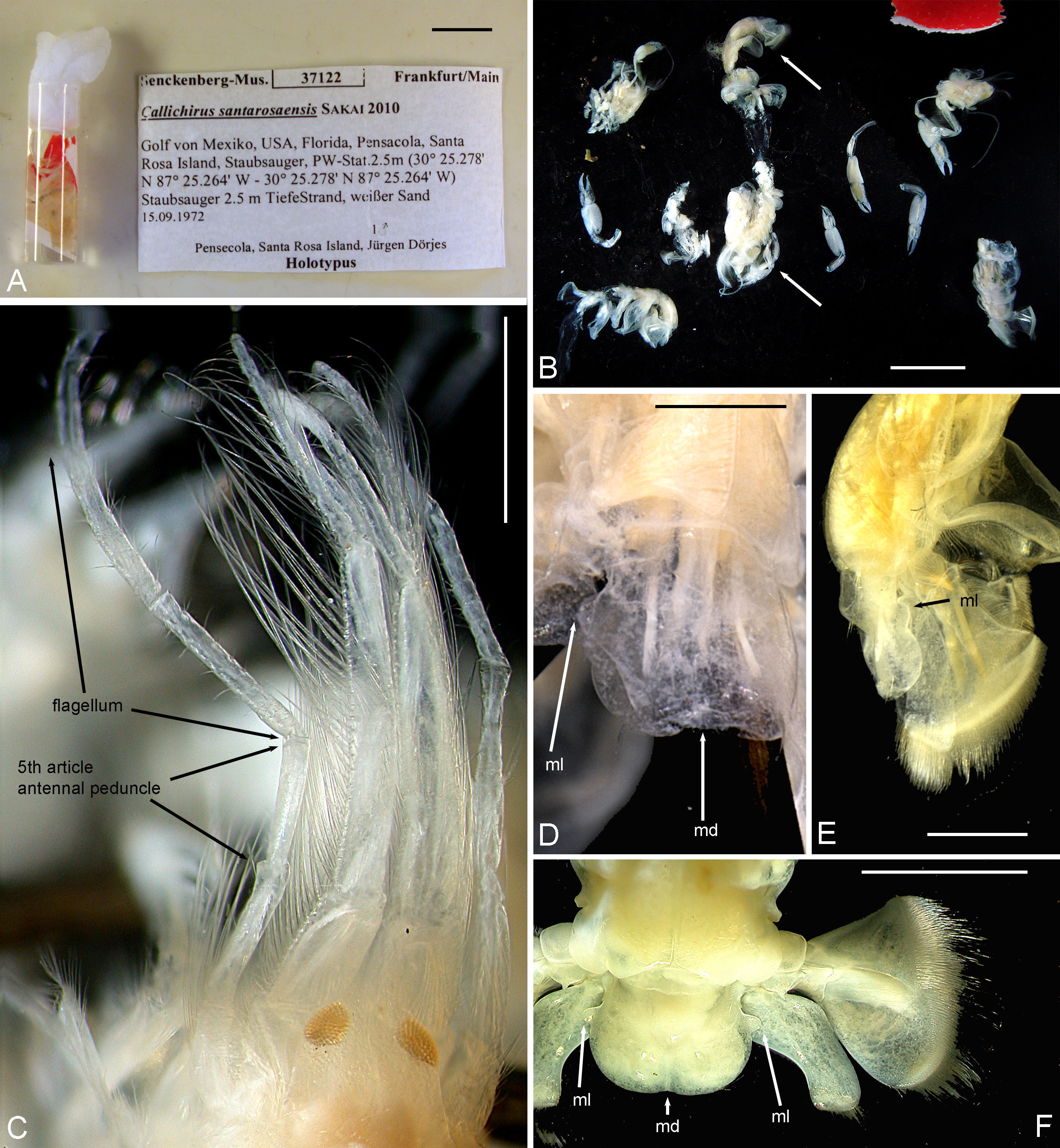

Fig. 2A–E View FIGURE 2. A – E

Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai & Türkay, 2012: 746 , fig. 10

Callianassa major . — Willis, 1942: 2 [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only, not " Callianassa major Say, 1818 "]; Williams, 1965: 101 [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only]; Felder, 1973: 22 –24, pl. 2, figs 10, 11 [not " Callianassa major Say, 1818 "]; Felder, 1978: 409 -429 [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only, not " C. major Say, 1818 "]; Rabalais et al. 1981: 105 [not " Callianassa major Say "]; Williams, 1984: 184 [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only].

Callichirus major . — Manning & Felder 1986: 439 [part, Gulf of Mexico population only, not " Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) "]; Abele & Kim 1986: 27 [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only, not " Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) "]; Rakocinski et al. 1993: 102; Felder & Griffis 1994: 1, 2, 45–47, figs. 1, 23; Staton & Felder 1995: 523–536, fig. 1A, 2, 3 [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only, not " Callichirus major (Say) "]; Adkinson & Heard 1995: 109 (not " Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) "]; Strasser & Felder 1998: 599–610 [part, Gulf of Mexico population only, not " Callichirus major (Say) "]; Strasser & Felder 1999a: 844–878 [part, Gulf of Mexico population only, not " Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) "]; Strasser & Felder 1999b: 211–222 [part, Gulf of Mexico population, not " Callichirus major (Say) "]; Felder 2001: 444 [part, Gulf of Mexico population only, not " C. major (Say) sensu stricto "]; Felder et al. 2009: 1092, footnote 109, [part, Gulf of Mexico populations only, not " Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) "; Robles et al. 2009: fig. 1 [part, Gulf of Mexico material only, not " Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) "].

Material investigated. SMF 37122, printed label: " Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai 2010 \ Golf von Mexico, USA, Florida , Pensacola, Santa / Rosa Island, Staubsauger, PW-Stat. 2.5m (30° 25.278'N \ 87° 25.264' W - 30° 25.278' N 87° 25.264' W) \ Staubsauger 2.5 m TiefeStrand, weißer Sand \ 15.09.1972 \ 1 ♂ \ Pensecola, Santa Rosa Island, Jürgen Dörjes \ Holotypus ".

Comparative material. Callichirus major ( Say, 1818) : USA, Gulf of Mexico, Louisiana, Isles Dernieres, Bayside ( ULLZ 13031); Atlantic Florida , Lake Worth, Peanut Island, ( ULLZ 13944); Brazil, Rio Grande do Norte, Pirangi Beach ( NHMW 25547). Callichirus islagrande ( Schmitt, 1935) : USA, Gulf of Mexico, Louisiana, Isles Dernieres, Bay side washover ( ULLZ 12968).

Comments. Sakai & Türkay (2012) described Callichirus santarosaensis based on " holotype, male (TL/CL, 23.0/ 4.2 mm, damaged and lacking larger cheliped, P4 and 5); 5 fragments (2 carapaces, 3 abdomens)". SMF 37122, labelled " Holotypus " (see Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2. A – E ) received on loan by us, consisted of a vial that contained among the holotype also the other fragments including 3 left and 1 right detached chelipeds (see Fig. 2B View FIGURE 2. A – E ). Fortunately, it was possible to recognize the holotype among all the fragments as it was the only "specimen" with pleon and tailfan still connected to the carapace by empty pleomeres 1 and 2 and represented corresponding characters as figured by the authors. In order to faciliate its future recognition, we have separated the holotype and put it in its own vial. On the basis of this damaged and immature material, Sakai & Türkay (2012) concluded that relative lengths of the antennular versus antennal peduncles, as well as shape of the telson, distinguished this new species from C. major ( Say, 1818) . However, their illustration misrepresents (fig. 10A), the terminus of the antennal peduncle, creating an artifact extension to the terminal article by failing to show proximal segmentation of the flagellum. This would be obvious to students of the group familiar with the degree to which peduncle segmentation of the antennae is conserved within the genus, and would have been readily apparent had direct comparisons been made to either specimens of C. major (from which the species was separated) or to quality illustrations in literature (for example, Williams 1984: fig. 127).

The telson was originally illustrated in a posterior abdominal portrayal but the illustration lacked detail of dorsal sculpture of both the telson and abdominal somites that is typical of adult congeners. Our investigation of the holotype showed that the authors missed the mid-lateral lobes of the telson (best visible in the decayed holotype in a more lateral view, see Fig. 2D, E View FIGURE 2. A – E ) that are characteristic of C. major ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2. A – E F). Also the median depression is visible in the holotype (compare Fig. 2D View FIGURE 2. A – E with 2F) and in one of the other pleon fragments. As previously noted for early postlarvae of Callichirus spp. ( Strasser & Felder 1999a, 2000) dorsal sculpture and telson shape are not so strongly evident in early stages as in adults. Many juveniles assigned to Gulf of Mexico and Florida Atlantic populations of Callichirus major (ULLZ 13031, 13944, respectively) and Gulf populations of Callichirus islagrande (ULLZ 12968), nearly equal in size to the holotype of this species, are similarly developed in these characters. Finally, the authors stated that their material lacked the major cheliped, but their illustrations labelled as minor chelipeds ( Sakai & Türkay 2012: Fig. C–E) could well represent typical variation and male asymmetry in that appendage. Our examination of these specimens and similar male and female juveniles of C. major from both populations in the Gulf of Mexico and those along the Florida Atlantic coast suggest these are major chelipeds.

This stated, there are no presently known morphological adult characters to separate this species from Callichirus major , so why not sink this new name? While curiously not mentioned by the authors, though in part cited previously in works by one of them ( Sakai 2005, 2011), several comparative studies have previously recognised the uniqueness of the northern Gulf of Mexico population on the basis of genetics, larval history, and larval behavior ( Staton & Felder 1995; Strasser & Felder 1998, 1999a, b, c), though none went so far as to assign a separate species name. Deferring to further analyses, several papers specifically noted the likely need for eventual taxonomic recognition ( Staton & Felder 1995; Felder 2001; Felder et al. 2009), but none reported morphogical differences that could support this. Sakai & Türkay (2012) erected a new name but the morphological diagnosis they furnished is of no value in distinction of it from C. major s.s., nor for that matter, from early juvenile stages of the sympatric northern Gulf of Mexico species, Callichirus islagrande . We have observed that juveniles of C. islagrande , much as adults (see Felder 1973), can be distinguished from both Florida Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico populations previously assigned to C. major by their more narrowed and protracted terminal process of the eyestalk and by the distal setation of the uropodal endopod that extends further onto the mesial margin. We have confirmed that they differ as well in these characters from the type of Callichirus santarosaensis .

Further complicating a decision on how to regard this proposed new name, the type locality given as a geographical position is the same as the authors give for Anomalaxius , discussed above, with a notable difference in that the habitat of Anomalaxius was described as shelf waters in 20 m while that of Callichirus santarosaensis was stated to be 2.5 m water depth, ostensibly off sandy beaches of Santa Rosa Island. In both cases, the published geographical position for the type locality turns out to be near inland shores of Perdido Bay, well west and somewhat inland of Santa Rosa Island.

Regardless of all these shortcomings, we find ample previously published evidence to justify that Callichirus populations in the northern Gulf of Mexico are indeed separate from Callichirus major s.s. and C. islagrande . We recommend the name Callichirus santarosaensis be applied to northern Gulf of Mexico populations formerly treated as C. major , but in the absence of morphological characters, this must be solely on the basis of geographical origins of materials, underpinned by genetic analyses (sensu Staton and Felder 1995) when possible. We do so, even though previously known geographic distributions for Gulf of Mexico populations assigned to Callichirus major fall just short of reaching east to the reported type locality of this new species (reaching to Perdido Key, but reported from neither Perdido Bay nor Santa Rosa Island), and even though C. islagrande , rather than its congener, is in our collections conspicuously abundant on beachfronts of Santa Rosa Island. Comparisons to comparably sized juveniles of Callichirus islagrande in museum holdings reveal differences in eyestalk development and setation of the uropodal endopod that rule out C. santarosaensis being confused with that species.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai & Türkay, 2012

| Felder, Darryl L. & Dworschak, Peter C. 2015 |

Callichirus santarosaensis Sakai & Türkay, 2012 : 746

| Sakai 2012: 746 |

Callianassa major

| Williams 1984: 184 |

| Rabalais 1981: 105 |

| Felder 1978: 409 |

| Felder 1973: 22 |

| Williams 1965: 101 |

| Willis 1942: 2 |