Safrina Reid & Beatson

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4150.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1D796B5E-8304-4514-BDD3-EF21A58E72BB |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6062531 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/24646FC6-99BB-4930-8368-1FF851E22B0C |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:24646FC6-99BB-4930-8368-1FF851E22B0C |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Safrina Reid & Beatson |

| status |

gen. nov. |

Safrina Reid & Beatson View in CoL , new genus

Type species. Ryssonotus laticeps Macleay, 1885 , this designation.

Etymology. Named in honour of Safrina Thristiawati. The generic name is feminine in gender.

Diagnosis. Ventral setae simple, not multifid; eyes completely divided; antennae geniculate, with 10 antennomeres, antennomeres 1–4 sparsely setose and symmetrical, antennomeres 5–10 at least partly densely setose, asymmetric, forming a loose club; mandibles strongly punctured, inner faces not densely setose; sides of head with prominent genal lobe; upper surface of head tuberculate, with deep pit at base; mentum small, semicircular, punctate and thickly sclerotised; pregular area thickened and strongly transversely raised, with grooved sides for retention of maxillary palpi; pronotal disc with foveolate depressions; posterior corners of pronotum deeply concavely excavate, not margined; prosternal process linear, not arched, hidden between procoxae; lateral margins of pronotum crenulate in female; lateral margins of elytra explanate; mesosternal process anteriorly excavate; aedeagal endophallus everted; male paraproct split into two sclerites; proctiger of ovipositor triangular with long apical spine; female paraproct split into two sclerites; vaginal palp reduced to a flat strongly sclerotised plate with long setae at apex; spermatheca present, globular.

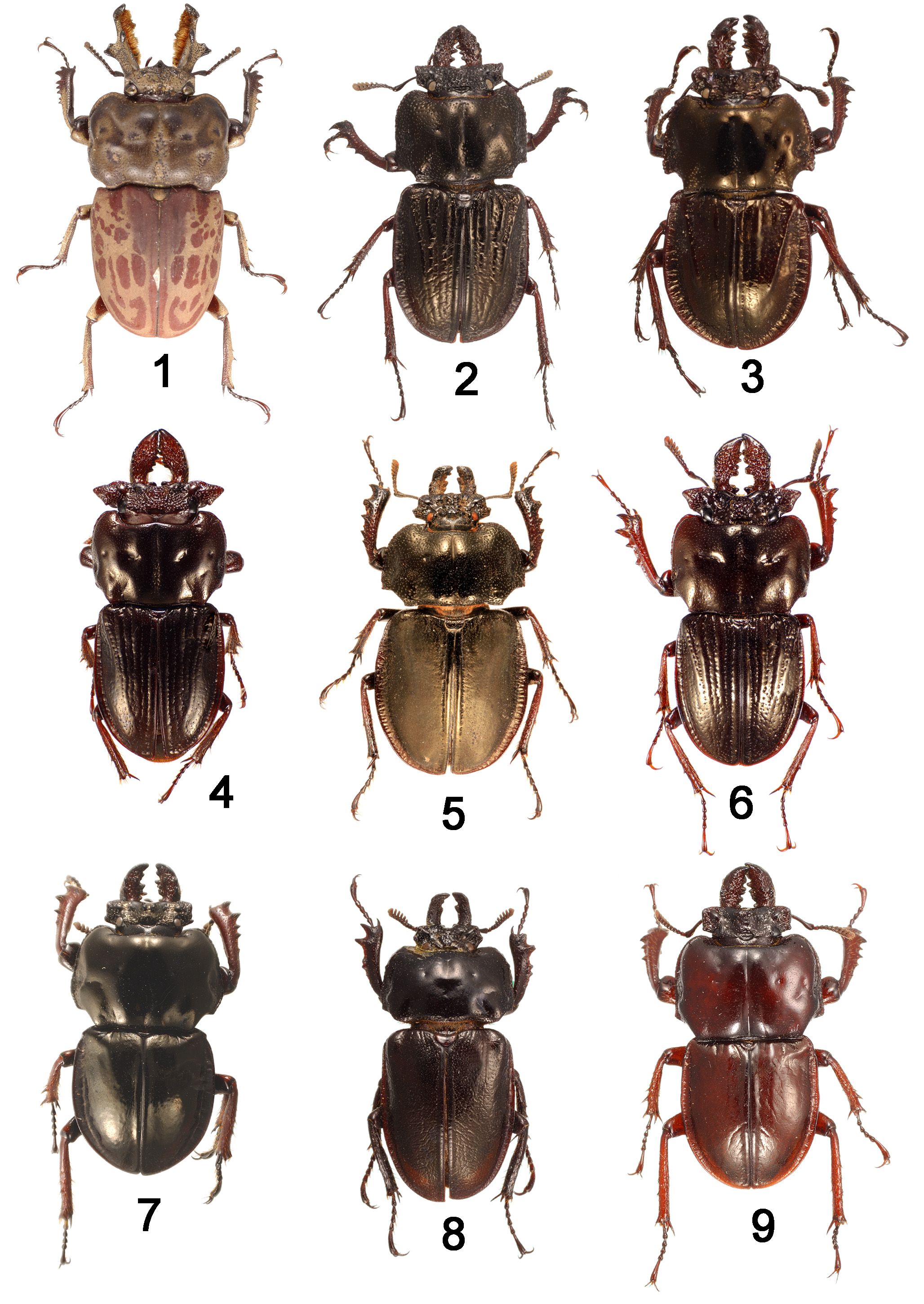

Description. Adult. Length: excluding mandibles, 14–26 mm; including mandibles 15−28 mm. Upper surface black to reddish brown, often with metallic green reflection, dull or shiny, smooth or rugose. Body oval with relatively small head. Head with sparse, erect, simple setae; most visible around median tubercles and on genal lobes; dorsal surface of pronotum (except margins) glabrous; elytra glabrous, except minute sparse stubble laterally and apically in S. jugularis ( Westwood, 1863) and S. parallela ( Deyrolle, 1881) . Ventral setae simple.

Head. Eyes completely divided by canthus, dorsal segment of eye much smaller than ventral, separated by at least height of dorsal segment in lateral view; head strongly punctured; sides of head with prominent genal lobe; head tuberculate between eyes, and with a deep lunate pit at base; antennae geniculate, with 10 antennomeres, antennomeres 1–4 sparsely setose and symmetrical, antennomeres 5–10 densely setose and asymmetric, forming a loose club; mandibles short, length less than width of head, strongly punctured, inner faces setose but without a dense brush, with multiple blunt tubercles (intraspecifically variable and often asymmetric); mentum relatively small, semicircular, punctate and sclerotised; pregular area thickened, strongly transversely raised, with convergent sides; gap between pregular ridge and base of mandible forming a groove for retention of maxillary palp.

Thorax. Pronotum transverse, quadrangular or broader at base, anterior angles rounded (produced in males), posterior corners strongly concave, forming distinct posterolateral angle; disc with depressed midline (broad and shallow in S. parallela ) and lateral foveolate depressions (intraspecifically variable and often asymmetric); at least posterior corners and anterior of pronotum without bevelled margin; lateral margins of pronotum usually feebly (male) or strongly (female) crenulate; anterior half of hypomeron smooth with sparse trichobothria; prosternum smooth, with scattered trichobothria, most species almost glabrous; prosternal process a level, unarched, ridge hidden between procoxae, which are almost touching; elytra parallel-sided at basal 2/3 to strongly ovate, narrowly elevated at sutural margin, flat and explanate at lateral margins; scutellum semicircular; wings variable, from fully formed to reduced to a short narrow strip half length of elytra; mesoventrite process anteriorly excavate, without a tubercle between mid coxae; meso- and metathoracic ventral sclerites closely punctured and pubescent; legs gracile; profemora much thicker than other femora, anteriorly ridged, the ridge with a preapical excavation (inner edge of excavation toothed in larger males); tibiae not carinate; number of tibial teeth intraspecifically variable and often asymmetric, protibiae with at least 4 large external teeth, mesotibiae with at least 2 small external teeth, metatibiae with or without external teeth; inner margin of protibia slightly excavate and usually with median teeth; tarsal empodium short, hardly projecting beyond ventral apex of fifth tarsomere, much less than half length of claws.

Abdomen. Ventrites not laterally ridged, without a deep basal groove. Aedeagal endophallus everted, unbranched; male tergite IX (paraproct) membranous at dorsal midline, split into two sclerites (laterotergites); male sternite IX with basal (anterior) elongate lobe and truncate setose apex; dorsal edge of parameres not notched, apices with membranous flange; proctiger of ovipositor triangular with long apical spine (4 species examined); female paraproct split into 2 sclerites; vaginal palp reduced to a flat strongly sclerotised plate with long setae at apex; spermatheca present, globular.

Larva. The following diagnostic description is based on mature specimens (instars unknown) of five species ( S. grandis ( Lea, 1915) , S. jugularis , S. laticeps , S. moorei new species, and S. polita ), identified by their association with adults.

Length 23−40 mm (when roughly straightened); third antennomere produced or truncate at apex; mandible with 1 apical tooth plus 5 internal subapical (scissorial) teeth; mesocoxal stridulatory file present as a fine line of coarse rounded granules, without basal area of finer granules; metatrochanteral stridulatory file present as a single ridge of 15−23 sparse, transverse granules; tibiotarsus not reduced, length about 3 times width at base; 10th abdominal segment dorsally foreshortened, with raster of moderately dense, short setae, at sides laterally directed, at middle posteriorly to inwardly directed, raster with fringe of short to very long setae; no dorsal anal lobe, lateral lobes with large well-defined oval pads, which are margined, smooth, and glabrous.

Notes. Safrina is easily distinguished from Ryssonotus , differing by at least 13 adult and two larval characters: adult: upper surface without mottled colour pattern ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1 − 9 ); ventral setae simple, not multifid; head with prominent genal lobes ( Fig. 20 View FIGURES 19 − 27 ); eyes separated widely in lateral view ( Fig. 39 View FIGURES 39 − 43 ); antennal club with six partly densely setose antennomeres ( Fig. 38 View FIGURES 37 − 38 ); inner face of mandibles not densely setose ( Fig. 20 View FIGURES 19 − 27 ); posterior corners of pronotum deeply concavely excavate ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1 − 9 ); prosternal process flat, hidden between coxae ( Fig. 45 View FIGURES 44 − 45 ); lateral margins of elytra broadly explanate ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1 − 9 ); male paraprocts not fused ( Fig. 51 View FIGURES 50 − 51 ); proctiger of ovipositor triangular with long apical spine ( Fig. 62 View FIGURES 61 − 62 ); female paraproct split into two sclerites; vaginal palp reduced to a flat strongly sclerotised plate with long setae at apex; spermatheca hard, globular; larva: tibiotarsus elongate, length 3x breadth ( Fig. 66 View FIGURES 63 − 67 ); raster with inner setae apically or inwardly directed ( Fig. 67 View FIGURES 63 − 67 ).

Safrina View in CoL and Ryssonotus View in CoL are most similar to Australognathus Chalumeau and Brochier, 1995, from North Queensland ( Moore 1978; Moore & Monteith 2004); Sphaenognathus Buquet, 1838 from South America ( Onore 1994); and Chiasognathus Stephens, 1831 View in CoL from South America ( Onore 1994; Paulsen & Smith 2010), as intimated by Westwood (1863). The nomenclature of these genera is complex. Sphaenognathus and Chiasognathus View in CoL were split into 7 genera based largely on trivial secondary sexual characters ( Chalumeau and Brochier 1993, 1995; Molino- Olmedo 2001), which are unlikely to provide a strong phylogenetic signal. Paulsen & Smith (2010) have discussed some of these genera and rejected their validity. However, one of these genera, Australognathus, was named for an Australian species of Sphaenognathus . Moore & Monteith (2004) discussed the status of Australognathus and reduced it to a subgenus, noting that it was based on minor male characters, but that there were biological differences between the two taxa. Paulsen (2010b), in a discussion of the separation of Chiasognathus View in CoL from Sphaenognathus , accepted the validity of Australognathus as a genus, but without explanation. Most recently, Kim & Farrell (2015) have provided evidence for the ancient divergence of the Australian and South American species in this group, supporting the recognition of Australognathus as a valid genus, sister to Sphaenognathus + Chiasognathus View in CoL . Kim & Farrell (2015) also discussed the composition of Chiasognathini View in CoL and noted that Chiasognathini View in CoL , “Rhyssonotini” [an unavailable name: Bouchard et al. 2011], “Pholidotini” [an unavailable name], and “Colophonini” [an unavailable name] formed a monophyletic group. They failed to provide morphological justification for any of their generic groups and made no classificatory changes.

Ryssonotus View in CoL and Safrina View in CoL are hereby placed with Australognathus, Chiasognathus View in CoL , and Sphaenognathus in the tribe Chiasognathini View in CoL , defined by the club of 5 or 6 antennomeres, completely divided eyes, female externally keeled mandibles, female head with blunt median dorsal tubercle in front of an excavation (shallow to absent in Ryssonotus View in CoL ), plus other features listed by Moxey (1960). Molecular data support this monophyletic group ( Kim & Farrell 2015).

Australognathus, Chiasognathus , and Sphaenognathus differ from Safrina and Ryssonotus by: adult: lack of dorsal cephalic tubercles in males, flat pregula, profemora without anterior ridge, long tarsal empodium; larva ( Onore 1994): mandibles with fewer internal (scissorial) teeth, pars stridens on metathoracic coxa with a diffuse patch of granules at apex. The larva of Australognathus munchowae Moore & Monteith, 2004 , is similar to that of Sphaenognathus , with two scissorial mandibular teeth, metatrochanteral stridulatory file dense, with> 50 transverse tubercles, tibiotarsus reduced to short lobe and apex of metatrochanter strongly produced (material examined by CAMR in ANIC). Morphology therefore supports molecular analysis in placing Australognathus, Chiasognathus , and Sphaenognathus in a single clade ( Kim & Farrell 2015). Without a detailed study of the male and female genitalia and larvae, the precise relationships of these five genera are unclear.

Two genera related to the above are Cacostomus Newman, 1840 (= Eucarteria Lea, 1914 ; Reid 1999) in Australia, and Casignetus MacLeay, 1819 (= Pholidotus MacLeay, 1819 ) in South America, both placed in a poorly defined tribe Casignetini ( Kikuta 1986; Reid 1999), incorrectly named “Pholidotini” in Kim & Farrell (2015). Casignetini genera share several attributes with Chiasognathini (split eyes, rugose mandibles, semicircular mentum, and posterolaterally excavate pronotum), but have several characters that appear to exclude them from this tribe: three antennomere club, non-carinate mandibles, dorsal scale-like pubescence, notched parameres, and two-segmented vaginal palpi ( Reid 1999). The larvae of Casignetus are similar to Chiasognathini ( Costa et al.1988). Casignetini and Chiasognathini are probable sister groups and the morphological evidence for this is supported by molecular analysis ( Kim & Farrell 2015). All other extant lucanid genera, including South African Colophon Gray, 1832 ( Switala et al. 2014) , appear to differ considerably from the above genera, at least in external morphology.

The fossil lucanid Protognathinus Chalumeau and Brochier, 2001 , described in Chiasognathini , has Safrina - like antennae, mandibles, and pronotum, but it has complete eyes, unlike Chiasognathini and most other Lucaninae ( Holloway 1969) . This fossil appears to lack the morphological attributes that would place it in any known tribe ( Paulsen 2010b). Protognathinus is best treated as incertae sedis in Lucanidae , although it has been suggested that it belongs to Lampriminae ( Paulsen 2010b; Kim & Farrell 2015).

Natural history and conservation of Safrina . Unlike Ryssonotus , the larvae of Safrina prefer old dead wood infected with brown-rot fungi (J. Hasenpusch, personal communication 2004). Both adults and larvae occur under and within logs deeply embedded in soil (R. DeKeyzer, personal communication, 2014; C.A.M.R., personal observation). The adults may be sap feeders and are frequently collected in pitfall traps, including the volant species. The species occur in a variety of habitats, from Eucalyptus woodland to temperate rainforest, generally at moderate to high elevations. Adults and larvae are recorded from logs and trunks of Nothofagus and Eucalyptus .

Only one species of Safrina can be described as widespread and fairly common, the volant S. jugularis , but several populations of this species are small and isolated. The other species are known from few collecting events and several have small ranges. These other species should be considered threatened from habitat loss, changed fire regimes and over-collection. Safrina species largely occur in protected or extensive forests, but the rarely collected S. dekeyzeri new species has already lost one population due to clearance (B. Moore, personal communication 2004).

Over-collecting is likely to become a significant problem (ironically, this paper may be a factor) as lucanids are popular with collectors, especially in North America , Europe, and Japan . Collecting lucanids is most popular in Japan, where they have special cultural significance from early childhood (J. Morimoto, personal communication 2004) and are traded in commercially significant numbers ( Cornell & Honda 2002), which is causing damage to the Japanese lucanid fauna due to poor quarantine procedures ( Goka et al. 2004). The dealers who satisfy obsessive collectors are not interested in conservation. Two Japanese dealers were successfully prosecuted in Australia in 2003 for illegal collection of more than 1000 specimens of Lamprima insularis Macleay, 1885 , endemic to a small Pacific island, Lord Howe. During the lengthy preparation of this revision of Ryssonotus , the lucanid collecting community became aware of my work and one Japanese dealer offered " Rhyssonotus keyzerski " males for €1500 (AUS$3000) each and pairs of " R. costatus " for €1200 (AUS$2400) (www.eurofauna.com; seen September 2006). On the same website a male of the recently described Australognathus munchowae ( Moore & Monteith, 2004) , a species only known from protected areas, was offered for €5000 (AUS$10,000). These large sums place the financial gain of lucanid dealing on a par with illicit drugs ( Cornell & Honda 2002). While much of the collecting in Australia is done without permits, even the magnitude and impact of permitted collecting in National Parks is rarely monitored (C. A.M.R., personal observation).

The taxonomic revision of collectable organisms, which must be done to enable their conservation, also flags rarities for collectors. This is a well-known problem in herpetology, where new species in particular become collectors’ targets ( Stuart et al. 2006). To protect some of the species described below we omit details of collecting localities.

For conservation of Safrina species, we recommend: (i) vulnerable species status for S. dekeyzeri , S. moorei , and S. politus , under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (New South Wales); (ii) modelling of suitable habitat and field survey for all species except S. jugularis ; (iii) approved rearing programmes to improve knowledge of habitat requirements and to supply collectors' demands; (iv) improved regulation and policing of the insect trade; (vi) closer monitoring of approved collecting.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Safrina Reid & Beatson

| Reid, C. A. M. & Beatson, M. 2016 |

Sphaenognathus

| Buquet 1838 |

Chiasognathus

| Stephens 1831 |