Cryptotis parvus (Say, 1823)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6870843 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6869808 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/3D474A54-A00D-8762-FAF4-AC051864F83B |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Cryptotis parvus |

| status |

|

102 View On .

North American Least Shrew

French: Petite Musaraigne / German: Nordamerika-Kleinohrspitzmaus / Spanish: Musarana minima de Norteameérica

Other common names: American Least Shrew, Least Shrew

Taxonomy. Sorex parvus Say, 1823 ,

“Engineer cantonment.” Identified by J. K. Jones, Jr. in 1964 as “ Washington County, Nebraska, about five miles [= 8 km] north of the Douglas-Washington county line at a place approximately two miles [= 3 km] east of the presentvillage of Ft. Calhoun. ”

Cryptotis parvus is in the C. parvus group with C. berlandieri , C. soricinus, C. pueblensis, C. tropicalis , and C. orophilus, all of which used to be subspecies of C. parvus. N.

Woodman suggested recognizing C. orophilus and C. tropicalis as distinct species, which were first recognized as distinct by R. Hutterer in 2005, and C. tropicalis was then validated by L. N. Carraway in 2007. A. B. Baird and colleagues in 2018 determined that C. parvus was sister to a clade including C. orophilus and C. tropicalis and established that the C. parvus group was sister to a clade including the C. goodwini group and the C. goldmani group. P. A. Moreno in 2017 found that the C. parvus group wassister to all other species of Cryptotis ; additional sampling from all groups is needed to clarify these relationships. Specific status of C. berlandieri , C. soricinus, C. pueblenss, and subspecies floridanus is somewhat controversial. Cryptotis berlandier: and C. pueblensis are recognized as species based primarily on their distinct morphology and limited genetic data presented by L. Guevara and F. A. Cervantes in 2014, in which C. parvus wassister to a clade including C. berlandieri and C. pueblensis. Cryptotis soricinus has not been included in any genetic studies, but its population is morphologically distinct and has a disjunct distribution. Subspecies floridanus might be a distinct species, as indicated in S. J. Hutchinson in 2010 based on morphometrics (seven cranial measurements) and limited genetic data, but additional research is needed to validate this and their distributions because specimens from Tennessee and Ohio clustered with Florida and southern Georgia specimens of floridanus, while some specimens from Florida clustered with other C. parvus. In the same study, specimens of C. berlandieri in southern Texas and north-eastern Mexico were morphometrically similar to C. parvus, and the species was regarded as a subspecies of C. parvus, although no genetic studies were conducted on these specimens and the morphometrics were based on only a few variables. Hutchinson in 2010 also found that there might be at least two, if not three, major clades in C. parvus that are separated by the Mississippi River (eastern and western). The third possible clade is a southern clade that was found only in northern Florida. Genetic analyses by Baird and colleagues in 2018 also supported these two

major clades; their specimens from east and west of the Mississippi River had high genetic distances. Taxonomy presented here for the C. parvus group is very tentative, and additional studies are needed. Subspecies might represent distinct species, and there might be more subspecies in what is currently considered the nominate subspecies parvus. Two subspecies recognized.

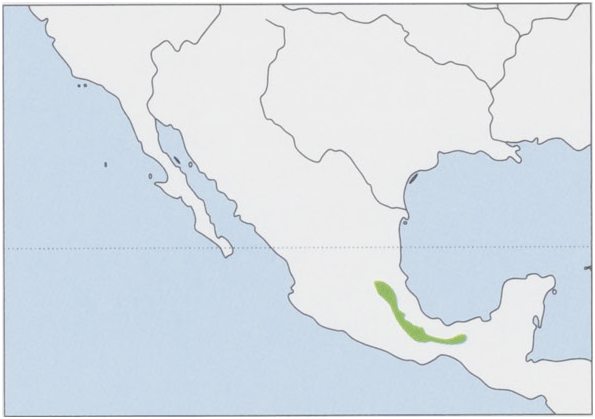

Subspecies and Distribution.

C. p. flonidanus Merriam, 1895 — NE Ohio, NW Tennessee, S Georgia, and N & S Florida; distributional limits are uncertain. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 52-68 mm, tail 13-23 mm, hindfoot 10-12 mm; weight 3-10 g. The North American Least Shrew is small, with fine, dense, short, and somewhat velvety fur. Dorsum is dull grayish brown to dark brown (nearly black) and varies between seasons, being browner in summer and grayer in winter. Venter is grayish brown to silvery gray. Forefeet are relatively broad, with short broad claws; feet are small and dusky in color. Tail is short (less than 45% of head-body length), covered with short hair, brown above, and slightly lighter below. Eyes are diminutive, and ears are small and barely visible under fur. Skull of least shrews has incomplete zygomatic arch, short rostrum, and slender rather than bulbous dentition; zygomatic processes extend posteriorly and ventro-laterally to below occlusal surface of teeth; and fourth unicuspid is tiny and obscured in lateral view of the skull. Teeth are reddish, and there are four unicuspids. Various species of mites (c.10 species; e.g. Orycteroxenus soricis, Dermacarus hypudaer, Androlaelapsfahrenholzi, and Eulaelaps stabularis), fleas (c.5 species; e.g. Corrodopsylla hamiltoni, Ctenophthalmus pseudagyrtes, Peromyscopsylla scotti, and Epitedia wenmanni), and chiggers (c.b species; e.g. Eutrombicula alfreddugesi, Neotrombicula sylvilagi, Euschongastia jonesi, and Pseudoschongastia farneri) have been recorded from the North American Least Shrew. The most commonly occurring species are O. soricis (a hypopial or migratory stage form), Androlaelaps jahrenholzi, Protomyobia clapareder, Hirstwonyssus talpae, Blarinobia cryptotis, Ctenophthalmus pseudagyrtes, and Corrodopsylla hamiltoni. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 52 and FN = 50 (in Texas).

Habitat. Generally grassy, weedy, and brushy areas, including grasslands, brushlands and forest clearings from sea level to elevations of ¢.905 m (relatively low elevation compared with most other species of Cryptotis ). Areas with large amounts of ground cover are favored, and in more southern parts of its distribution, the North American Least Shrew can be more common in wooded areas, although this is fairly rare. Some specimens have been captured in pine and pine-oak forests, wetlands, and agricultural fields.

Food and Feeding. North American Least Shrews are primarily carnivorous but somewhat omnivorous, eating a large variety of insects (various adult and larval beetles, lepidopterans, dipterans, and ornithopterans), arthropods (spiders, centipedes,etc.), earthworms, mollusks (snails, slugs), small vertebrates (frogs, lizards), and occasionally some plant material. They are voracious feeders, pouncing and biting heads of grasshoppers and crickets, attaching knees of northern leopard frogs (Lithobates pipiens) until they are immobilized, biting tails of lizards until they are detached before consuming them, and biting randomly on other invertebrates until they die. For larger grasshoppers and crickets, they might open up the abdomen and feed only on internal organs, and they might bite at their legs to immobilize them. North American Least Shrews must feed often to maintain their high metabolic rate. Two captive individuals consumed 3-5-8-1 g of food/day (average 5-5 g/day), and they drank often. Another captive individual that weighed c.4-7 g ate ¢.3-6 g of food/day. In Indiana, North American Least Shrews enter beehives to feed on the brood, giving them the local name “bee mole.” They have been reported to feed on the snail Melampus lineatus on Chincoteague Island, Virginia, although they rarely feed on snails on the mainland. Stomach contents of individuals in New York included earthworm fragments, adult beetles, and centipedes along with unidentifiable well-chewed insect parts. Similarly, stomach contents of North American Least Shrews from Illinois contained earthworms, insects, and other unidentifiable arthropods. In Indiana, stomach contents of 109 individuals included large amounts of various adult and larval insects, spiders, earthworms,snails, and slugs and smaller amounts of mites, fungal spores, and plant material. The five most frequent foods found in stomach contents of those 109 individuals were lepidopteran larvae (29-4%), earthworms (15:6%), spiders (11%), crickets and grasshopper internal organs (7-3%), and coleopteran larvae (7-3%). Food is often eaten on the spot, although North American Least Shrews will occasionally store food in burrows for later use. In one study on captive individuals, females killed and hoarded more prey than males, and for both sexes, various prey was stored differently (e.g. mealworms away from the nest and crickets near the nest).

Breeding. Reproduction of the North American Least Shrew occurs in March-November in northern populations but can occur year-round in southern populations. Copulation generally occurs all in one day, although it can take two days in some cases. Gestation lasts 21-23 days, and litters have 2-7 young. Young weigh c.0-3 g at birth. Young caravan attached to their mother for aboutthe first 10-11 days oflife, after which they stop latching onto the female but continue to follow her closely until ¢.21-23 days old. Weaning takes place at ¢.21-22 days old, and adult weight is reached at ¢.30 days old. Females can immediately breed again after giving birth. There have been reports of females killing their own young after birth. North American Least Shrews have lived up to 21 months in captivity, although they probably only live c.1 year in the wild. Nests are built aboveground in secluded areas, such as underlogs, rocks, dense brush, or any other concealing object, and usually consist of depressions or bare ground covered in dried leaves and grasses. Nests are 75-180 mm in diameter and vary significantly in size depending on numbers of individuals sharing them.

Activity patterns. The North American Least Shrew is active throughout the day and night, although activity peaks at night. It is terrestrial and semi-fossorial, using runways, building or stealing burrows, and creating nests in secluded areas aboveground. Much ofits time is spent frantically scurrying around searching for food and sleeping, which occurs more often when food is abundant. North American Least Shrews make expansive networks of runways, which are short and thin in width, and they might use runways of larger shrews and mice. Burrows that are either dug manually or stolen from other burrowing mammals. Burrows are less extensive than runways and can be up to 200 mm underground; they are also sometimes used to store food forlater use, especially when food is scarce. Runways and burrows can connect or lead to nests and can be extensive and complex, spreading from the nest. Fecal matter is generally dropped in piles near nestsites; piles can be nearly as large as the nest itself if the nest has been used for a long time (one record fecal pile was ¢.100 mm in diameter and 12 mm tall).

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Unusually, the North American Least Shrew is more social and less aggressive toward conspecifics than other soricine shrews. They are very cooperative, building burrow and runway systems and nests together, and they feed and sleep together most of the time. Many individuals can occupy a single nest (up to 31 have been reported) and will sleep together in a large huddle, which seems to be an adaptation to keep warm during colder seasons. Fights between individuals have never been recorded, and individuals are very mutualistic; there have been observations of multiple individuals feeding peacefully on the same food item. North American Least Shrews seem to rely more heavily on smell than sight when moving around and possibly also sound at the ultrasonic level, possibly using echolocation to navigate. They regularly make clicking and chirping sounds when exploring, and when young are separated from their mothers, they may make twittering sounds in an attempt to alert their mothers. When navigating, they make consistent ultrasonic pulses that might be used in echolocation. There are few estimates of densities and home ranges because North American Least Shrews are so hard to capture and follow. In Indiana, densities of at least 1-7 ind/ha (with a high of 4-9 ind/ha) were recorded, and home ranges were estimated at 0-17 ha for a male and 0-23 ha for a female.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List (as C. parva ). The North American Least Shrew has the widest and most northern distribution in the genus and is considered very common but hard to find. There are no major threats, and it seems to adapt well to human habitation and habitat degradation. North American Least Shrews are often used as model organisms because they are easy to maintain and breed.

Bibliography. Baird et al. (2018), Broadbooks (1952), Carraway (2007), Castro-Arellano (2014a), Choate (1970), Conaway (1958), Formanowicz et al. (1989), Genoways et al. (1977), Guevara & Cervantes (2014), Hall (1981), Hutchinson (2010), Hutterer (2005b), ICZN (2006), Jalili & Thomas (2001), Jones (1964), Merritt & Zegers (2014), Mock (1982), Mock & Conaway (1976), Moreno (2017), Reid (2006, 2009), Siemers et al. (2006), Whitaker (1974), Woodman (1993), Woodman & Morgan (2005), Woodman, Matson, Cuarén & de Grammont (2016b).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.