Caseya Cook & Collins 1895

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.177488 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5672578 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/2C6887A3-E036-FFAB-88E3-F84D8FC7F800 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Caseya Cook & Collins 1895 |

| status |

|

Caseya Cook & Collins 1895 View in CoL

Caseya Cook & Collins 1895:84 View in CoL ; Hoffman, 1979:138; Gardner & Shelley, 1989:223.

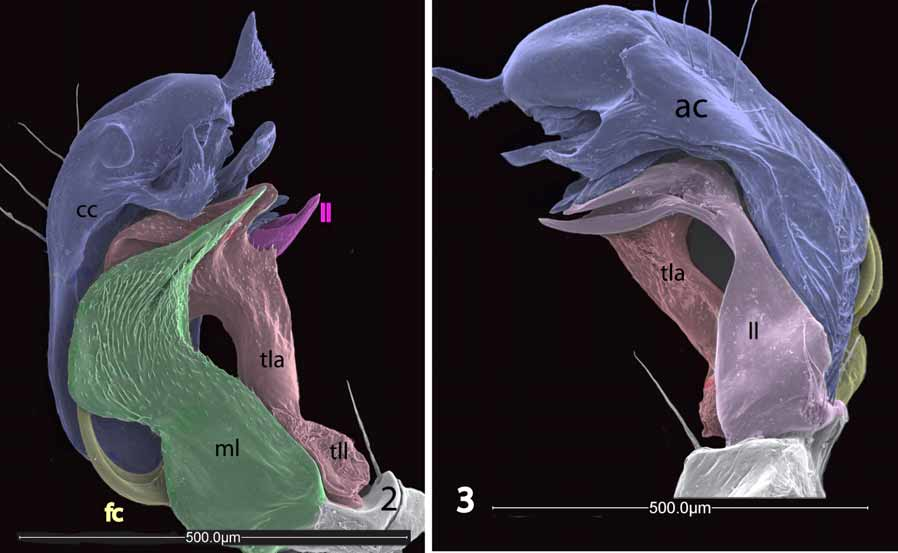

In their review of the caseyids, Gardner and Shelley (1989) proposed a terminology for the gonopods of Caseya View in CoL species that was based on a current, but incorrect, understanding of the homologies of the parts of the chordeumatidan gonopod. It is now generally accepted that in nearly all chordeumatidan gonopods, telopodite elements are absent, and the entire gonopod is developed from the coxa (in a few antholeucosomatid genera, a small, seta-tipped, articulated rod probably does represent the telopodite, but this structure is rare). Thus the gonopod parts can be attributed to either the angiocoxite (from the body of the coxa) or the colpocoxite (from the permanently extruded and sclerotized coxal gland). In their diagram of a dissected Caseya heteropa disjuncta View in CoL gonopod (their Figs. 111–117), the following changes are required to bring the terminology of Gardner and Shelley (G&S) into compliance with today’s interpretation; these changes are based on detailed study by WAS of the gonopods of all genera of Caseyidae View in CoL and comparative work with 15 other families of Chordeumatida View in CoL . The labeling on our Figures 2 and 3 View FIGURE 2, 3 reflect the changed terminology.

The telopodite of G&S is the colopocoxite (tla; blue). Strong evidence for this is found in the presence at the posterior base of this structure of a membranous region representing an unsclerotized part of the gland (tll, red); homologous (though much larger) structures appear in the related family Striariidae ). While it seems clear the rest of the gonopod is angiocoxal, we can refer to the piece G&S called the colpocoxite as the angiocoxite per se (ac, red). The other elements of this extremely complicated structure, called by G&S the coxal plate, lateral lamina, (ll, violet) mesal lamina (ml, green) and flagellocoxite (fc, yellow), may, for clarity, retain those names with the understanding that they are very likely angiocoxitic in origin.

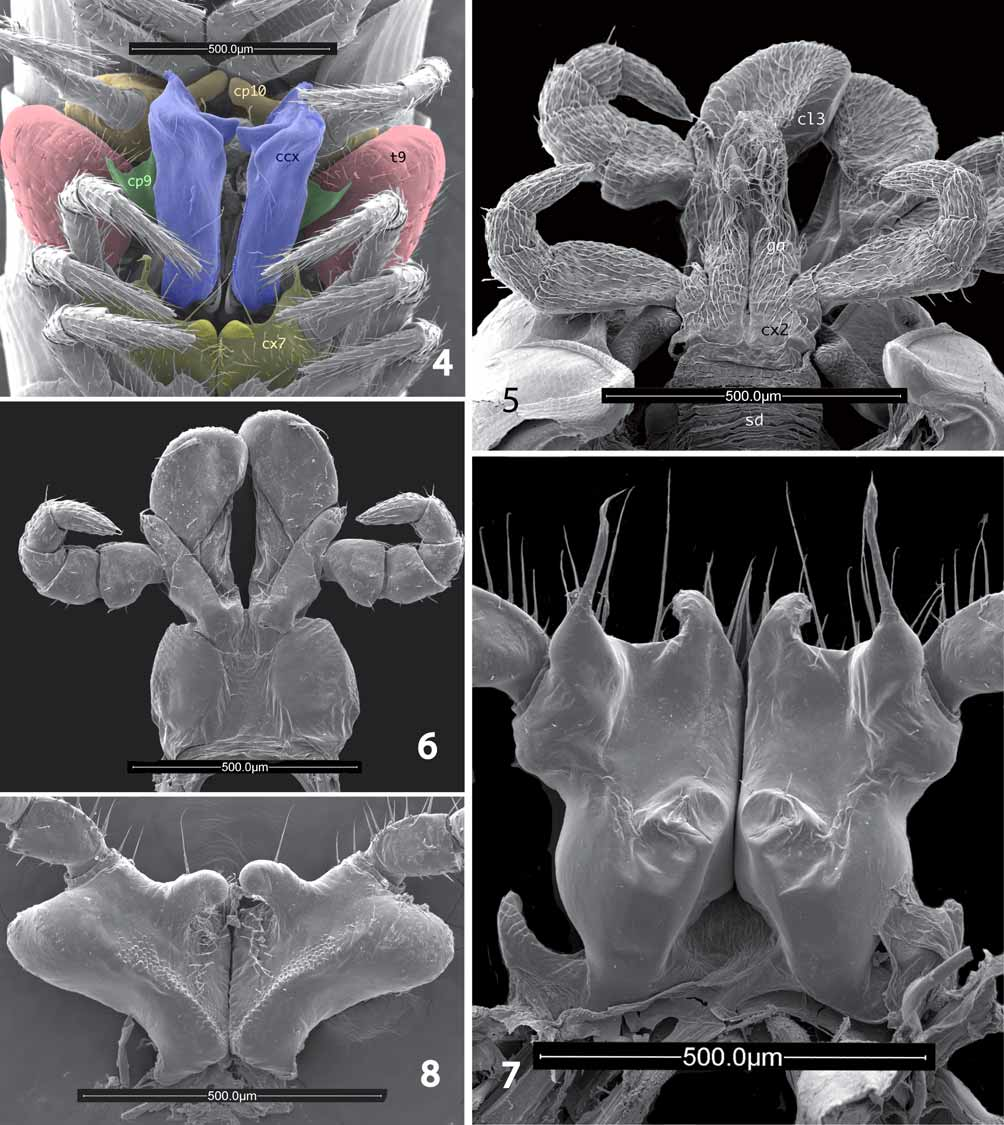

Similarly, the ninth legs ( Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 – 10 ) are referred to by G&S as posterior gonopods, implying a role in spermatophore transfer. But clearly they serve for the most part only to secure the gonopods in place ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 – 8 ) and protect them while they are retracted. For this reason we follow current usage and refer to these modified appendages as ninth legs. The telopodites of these legs are reduced to single, swollen, button-like structures (t9, red, Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 – 8 ; see also Fig. 9 View FIGURE 9 – 10 ) that are easily visible to the naked eye and allow the collector to identify mature males.

Species of Caseya also have an elaborate set of modifications to the second, third, seventh, and tenth legpairs. The second coxae bear long, caudally curved, setose gonapophyses associated with the seminal pore (ga, Fig, 5). The third coxae are greatly swollen and extend ventrally as flattened, rounded lobes ( Figs. 5, 6 View FIGURE 4 – 8 ). Very heavy musculature is associated with these legs, so that preserved male Caseya often have a “hunchbacked” appearance at the third and fourth diplosegments due to their strong contraction. The coxae of the seventh legs are also enlarged and display a number of blunt processes ( Fig. 7 View FIGURE 4 – 8 ), while the tenth coxae carry prominent coxal glands and yet another distinctive set of processes ( Fig. 8 View FIGURE 4 – 8 ). These modifications were briefly described for the genus as a whole by Gardner and Shelley (1989), but curiously only the second legs were sporadically illustrated for some of the species, and the descriptions under the species accounts of the modified legs are quite brief. Indeed, the tenth legs, with their strongly modified coxae, are described only as “enlarged” and bearing coxal glands. Our experience with many, but not all, of the species of Caseya tells us that these modifications contain taxonomic information and differ between species. Certainly the complex gonopods remain the prime characters whereby Caseya species may be identified, but in many cases the other modifications are easier to see. These modifications may also be useful phylogenetically, and so should be fully described and illustrated in the future, as we have done for C. richarti n. sp. below.

Finally, Gardner and Shelley (1989) unequivocally established the diagnostic utility of the cyphopods in Caseyidae , allowing the identification of females not accompanied by males. These structures should be illustrated as well, and a new survey of their structure, which seems quite varied though it is often difficult to reconcile the posterior and lateral views of the structures depicted by Gardner and Shelley (1989), would be very useful. In particular, the form of the receptacle would seem to be diagnostic for most species, and there are accessory sclerotizations of the membranous capsule surrounding the cyphopods that may be of systematic value. From our brief study of the matter, it would seem that an anterior view of the receptacle ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 9 – 10 ) gives the most information.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Caseya Cook & Collins 1895

| Shear, William A. & Leonard, William P. 2007 |

Caseya

| Gardner 1989: 223 |

| Hoffman 1979: 138 |

| Cook 1895: 84 |