Physa marmorata Guilding, 1828

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.7664805 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/1603F877-FFFD-7665-2A99-96D4FF05CADF |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Physa marmorata Guilding, 1828 |

| status |

|

Physa marmorata Guilding, 1828 View in CoL

Physa marmorata Guilding, 1828: 534 View in CoL ; Paraense 1986: 459–469, figs 1–33.

Stenophysa marmorata: Te 1978: 206 View in CoL , table 22; Taylor 2003: 113–121, figs 95–109.

Aplexa marmorata: Appleton et al. 1989 View in CoL .

Physa mosambiquensis Clessin, 1886: 366 View in CoL , pl. 54, fig. 4; Connolly 1925: 189, fig. 23; 1939: 475, text fig. 41; 1945: 167; Appleton et al. 1989 [considered a synonym of marmorata View in CoL ].

Physa waterloti Germain, 1911: 322 View in CoL , fig. 57; Connolly 1945: 167 [synonymised under mosambiquensis View in CoL ]. Aplexa waterloti: Brown 1980: 213 , fig. 115; 1994: 249, 250, fig. 115.

This opinion is in agreement with that of Taylor’s (2003) revision of the Physidae View in CoL inasmuch as the material from both west and south-eastern Africa represents a single species that originated in South America, probably Brazil. Taylor considers, however, that the name Afrophysa brasiliensis View in CoL given to the West African snails by Starobogatov (1967) should be retained and should also apply to the southern African material. From a detailed comparative study of male genital morphology, he argues that the species marmorata View in CoL (as Stenophysa View in CoL ) is confined to the Caribbean islands (excluding Cuba) and a small area of the central American isthmus and that A. brasiliensis View in CoL is native to the southernmost state of Brazil, Rio Grande do Sul. This latter distribution is incompatible with translocation to Africa aboard slave trade ships (see below) which would have sailed from more northerly ports such as Rio de Janeiro, Salvador (formerly Bahia) and Pernambuco. Relatively few slaves were taken to Argentina (W.L. Paraense pers. comm.).

Origin of Physa marmorata in Africa

It seems clear that Tete was the first collection site despite no mention of any precise type locality by Clessin (1886).This is important because it points to an early introduction of P. marmorata to south-eastern Africa. It seems likely that it was introduced from Brazil or the Caribbean islands via Portuguese sailing ships between the 16 th and 19 th centuries, possibly as a consequence of the slave trade. Most slaves taken to Brazil came from Angola but a substantial number came from Mozambique, as well as parts of East Africa ( Magalhães & Dias 1944; de Lucena 1950; Harries 1981; Paraense 1997). In fact Harries (1981) noted that the slave trade between Mozambique, and Brazil and the Caribbean islands, flourished between about 1790 and the 1850s and that Quelimane, approximately 130 km north-east of the Zambezi River mouth, was ‘… the foremost slave embarkation point on the Mozambican coast’. It is possible therefore that P. marmorata was introduced to Mozambique during the height of the slave trade, i.e. during the decades immediately preceding its discovery at Tete by Peters.

A question raised by D.W. Taylor (in litt. to D.S. Brown, 13.1.1988) is relevant here, viz. why was the only known locality for P. mosambiquensis situated inland at Tete and not on the coast? He speculated that the specimens may have represented the spread inland from an inoculum on the coast. The answer may lie in the fact that, as the enforcement of the prohibition of slavery began to take effect in the late 1830s, slavers avoided recognised ports and instead used hidden embarkation points such as river mouths. Dr Livingstone demonstrated with the Ma Robert in 1858, that the Zambezi River was navigable for small steamers as far as the rapids at Tete, approximately 410 km from the coast. An intriguing twist to this practice was a claim by Livingstone , quoted in a footnote in the foreword to Volume IV of Peters (1852–1882) accusing the Portuguese authorities in Mozambique of deliberately producing maps which showed the mouth of the Zambezi as the Kwakwa River at Quelimane , nearly 100 km north of its true position. This error was perpetuated in maps issued later by the Colonial Minister of Portugal and was, so Livingstone believed, designed to induce British ships enforcing the ban on slave trafficking, to station themselves well north of the real embarkation point. Whatever the case, slave trading from secluded embarkation points in defiance of the ban would have given traders direct access to natural fresh waters and, in the case of the Zambezi, to villages well inland .

Long-distance translocation of freshwater invertebrates aboard sailing ships is not far-fetched. The mosquito Aedes aegypti , vector of yellow fever, is believed to have been transported from West Africa to South America and the Caribbean islands in water barrels on slaving ships in the early 1600s ( Spielman & D’Antonio 2001). Dumont & Martens (1996) suggest that the cladoceran Alona weinecki and an ostracod Sarscypridopsis sp. , both sub-Antarctic species, were introduced to Easter Island by human agency. Indeed, the appearance of A. weinecki in cores from the lake in Rano Raraku crater coincides with Captain Cooke’s visit to the island in 1774 (H. Dumont pers. comm.).

In view of the distance of over 1500 km between the recent finds in South Africa and the 1886 record of P. mosambiquensis in Mozambique (at Tete), it is tempting to relate these two records, and to propose that the species has been in south-eastern Africa for as long as 200 years. Although the species was not recorded by malacologists working in Mozambique during the 1950s and 1960s ( de Azevedo et al. 1961), its recorded occurrence in the lowlands of eastern South Africa since 1986 indicates its spread in a broader region. Opinion of two former researchers at the Siegfried Annecke Institute in Tzaneen (Limpopo Province) was that the Tzaneen population (see Appleton et al. 1989) had been translocated there from somewhere in south-eastern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) by an official of the Union of South Africa Health Department working at the Institute. If true, this suggests an unusually long lag period and an exceptional example of the ‘long fuse big bang’ scenario thought to be common among invasive organisms ( Williamson 2000). Bearing in mind Germain’s (1911) comment that P. waterloti seemed to be a recent introduction to West Africa and suggestions by other authors (e.g. Te 1978) that it was probably introduced from the Caribbean via the slave trade, there might have been a lag period before the species was actually found in West Africa as well.

During the 18 years since its appearance in Durban, P. marmorata has spread widely over the city’s metropolitan area and into the eastern lowlands of South Africa, particularly in the northern half of KwaZulu-Natal (see below). A second record for Mozambique, a wetland at Ponta da Ouro in the extreme south of the country, just north of the border with KwaZulu-Natal, was made by P.E. Reavell in May 2004 but this is probably an extension of its northwards spread through KwaZulu-Natal .

This picture is however complicated by an enigmatic record by Brand et al. (1967) of P. mosambiquensis from the low gradient Valley Sand Bed Zone (head of estuary to 233 m altitude) of the Umgeni River, Durban. The collections on which Brand et al.’s survey was based were made between 1958 and 1962 by the National Institute for Water Research, Durban, but the location of the material is not known and the identification cannot be checked.Although this record may have been based on elongate specimens of P. acuta (it coincides with the first report of P. acuta in South Africa, viz. Umsinduzi River, Pietermaritzburg, 1958), the Umgeni River runs close to Pinetown where P. marmorata was discovered in 1986, about 25 years later. P. marmorata may therefore have been introduced into South Africa in the 1950s but did not become invasive until the 1990s.

Strangely P. mosambiquensis View in CoL was not recorded by Schoonbee (1964) in his account of the 1958–1962 Umgeni River survey which also formed the basis for Brand et al.’s later 1967 report. More mollusc species were however recorded from the Valley Sand Bed Zone of the Umgeni by Brand et al. (1967) than by Schoonbee (1964) and this appears to be due to more careful identification by Brand et al. Schoonbee may not have recognised the physid since this family was at that time virtually unknown in South Africa.

Distribution of Physa marmorata in South Africa

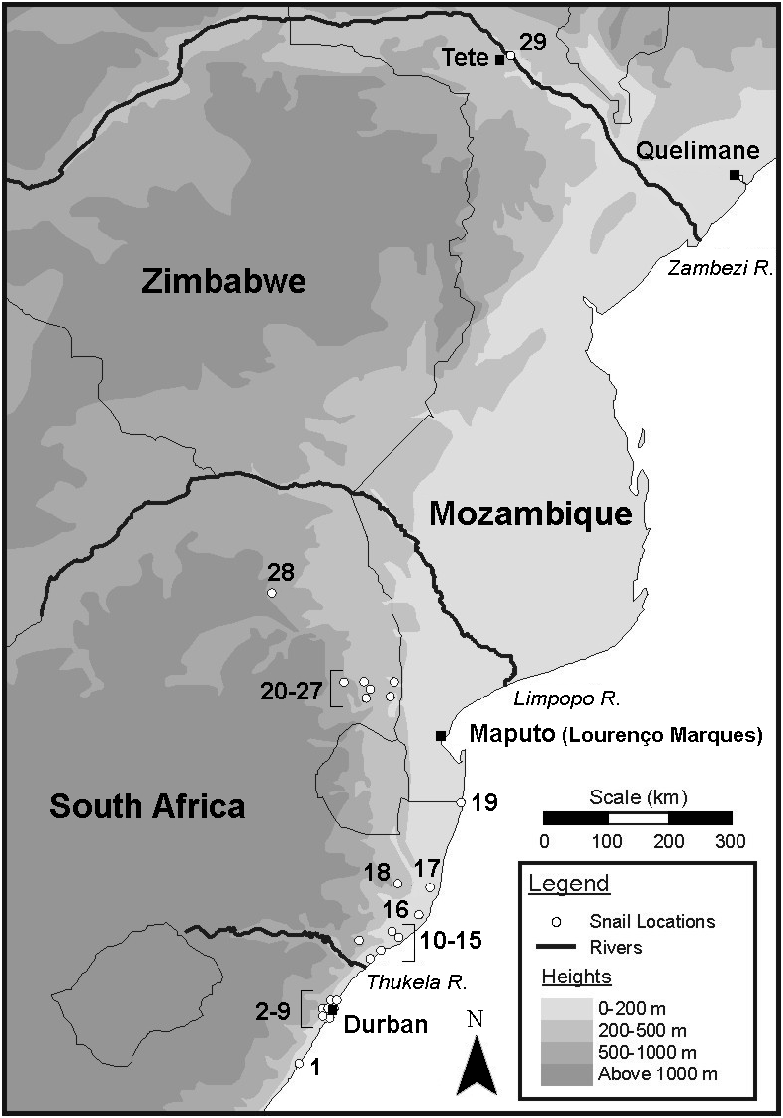

P. marmorata is spreading in South Africa and has become the third most widespread invasive freshwater snail in the country after Lymnaea columella and P. acuta ( Appleton & Brackenbury 1998; Appleton 2003). Since its discovery in the Durban area in 1986 it has been collected from 29 localities in the low-lying parts of three eastern provinces, mostly in KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga, with an isolated record in Limpopo (Table 2, Fig. 4 View Fig ).

These localities all lie below an altitude of 726 m, with 26 (89%) below 500 m and 20 (69%) below 200 m on the coastal plain. They include many types of lentic waterbodies, both natural (e.g. streams, small lake, pools and pans) and artificial (e.g. dams, canals and concrete-lined ponds). Exceptions are the records from a backwater in the perennial Sabie River and three seasonal streams in the Kruger National Park, Mpumalanga ( de Kock & Wolmarans 1998; de Kock et al. 2002). Notes on these watercourses (K.N. de Kock pers. comm.) describe low snail densities in clear, slowly flowing water with substrata of sand, stone and decaying organic matter and generally sparse emergent and/or floating vegetation.

Since habitats in most localities ( Fig. 4 View Fig ) are lentic or slowly flowing, it seems that, compared to the related P. acuta , P. marmorata is less able to colonise large flowing watercourses. This may explain its virtual absence from the country’s major river systems, a factor that could be slowing its spread. However, the aggregation of localities (numbers 20–27) in the southern part of the Kruger National Park, an area where dispersal by human agency can probably be discounted, suggests that similarly comprehensive surveys in other areas would show a wider geographic distribution. The study by de Kock et al. (2002) ascribed the species’ spread in this area between 1995 and 2001 to passive transport via floods during a period of abnormally high rainfall. Annual rainfall figures measured during this period at five stations in the newly colonised area ranged from 39 to 95% (mean 69%) higher than the mean of the previous five years (466 mm).

Interspecific differences in habitat preference were also observed by the senior author in rivers, streams and irrigation furrows in several districts of Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, in August 2000. Physa cubensis — equated with P. acuta by Paraense and Pointier (2003) —was the only physid present (often abundant) in larger, flowing rivers, while both it and P. marmorata occurred (though only in moderate numbers) in smaller channels where flow was generally slight or lacking.

A similar situation was observed in Puerto Rico, where Harry and Hubendick (1964) noted that P. marmorata and P. cubensis had different habitat preferences. They reported that ‘ P. cubensis occurs in the larger streams of low gradient, but P. marmorata does not seem to occur there. P. cubensis extends into the steeper gradient headwater streams where the individuals are small and rare, but P. marmorata was not found in such habitats’.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Physa marmorata Guilding, 1828

| Appleton, C. C. & Dana, P. 2005 |

Stenophysa marmorata:

| TAYLOR, D. W. 2003: 113 |

| TE, G. A. 1978: 206 |

Physa waterloti

| BROWN, D. S. 1980: 213 |

| GERMAIN, L. 1911: 322 |

Physa mosambiquensis Clessin, 1886: 366

| CONNOLLY, M. 1925: 189 |

| CLESSIN, S. 1886: 366 |

Physa marmorata

| PARAENSE, W. L. 1986: 459 |

| GUILDING, L. 1828: 534 |