Paradelia Ringdahl

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.178592 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D1A14994-A95A-4B0E-B52F-9DAC4DDCBFDC |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6236379 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0B722F74-FF86-FFFC-FF49-FF544129BE67 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Paradelia Ringdahl |

| status |

|

Genus Paradelia Ringdahl View in CoL View at ENA

Paradelia Ringdahl, 1933a: 33 View in CoL (as subgenus of Hylemya View in CoL [as ‘ Hylemyia ’] Robineau-Desvoidy). Type-species Pegomyia lundbeckii Ringdahl, 1918 , by monotypy.

Pegomyiella Ringdahl, 1938: 191 (as subgenus of Pegomya View in CoL [as ‘ Pegomyia ’] Robineau-Desvoidy). Type-species Anthomyza lunatifrons Zetterstedt, 1845 , by original designation.

Pseudonupedia Ringdahl, 1959: 292 View in CoL . Type-species Anthomyia intersecta Meigen, 1826 View in CoL , by subsequent designation ( Huckett 1971: 76).

Description. Small to medium-sized anthomyiids (WL 3.1–6.5mm) with fully developed sexual dimorphism ( Figs. 1, 3 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ).

Male. Cuticle entirely dark brown to black, or certain parts (basal articles of antenna, palpus, coxae, femora, tibiae, abdomen) to varying extent coloured brown, dark reddish ochre, yellow ochre or yellow. Nearly all parts of body and appendages covered in lighter or darker olive grey to olive brown dusting. A pattern of three darker stripes tends to be visible in certain views on anterior mesonotum. Likewise, a dark mid-dorsal stripe, often even dark anterior bands, tend to be visible on tergites II–IV(–V) of abdomen. Prementum shiny brownish black to black, without any dusting. Even caudal segments of abdomen often sparsely dusted and to varying extent appearing shiny black.

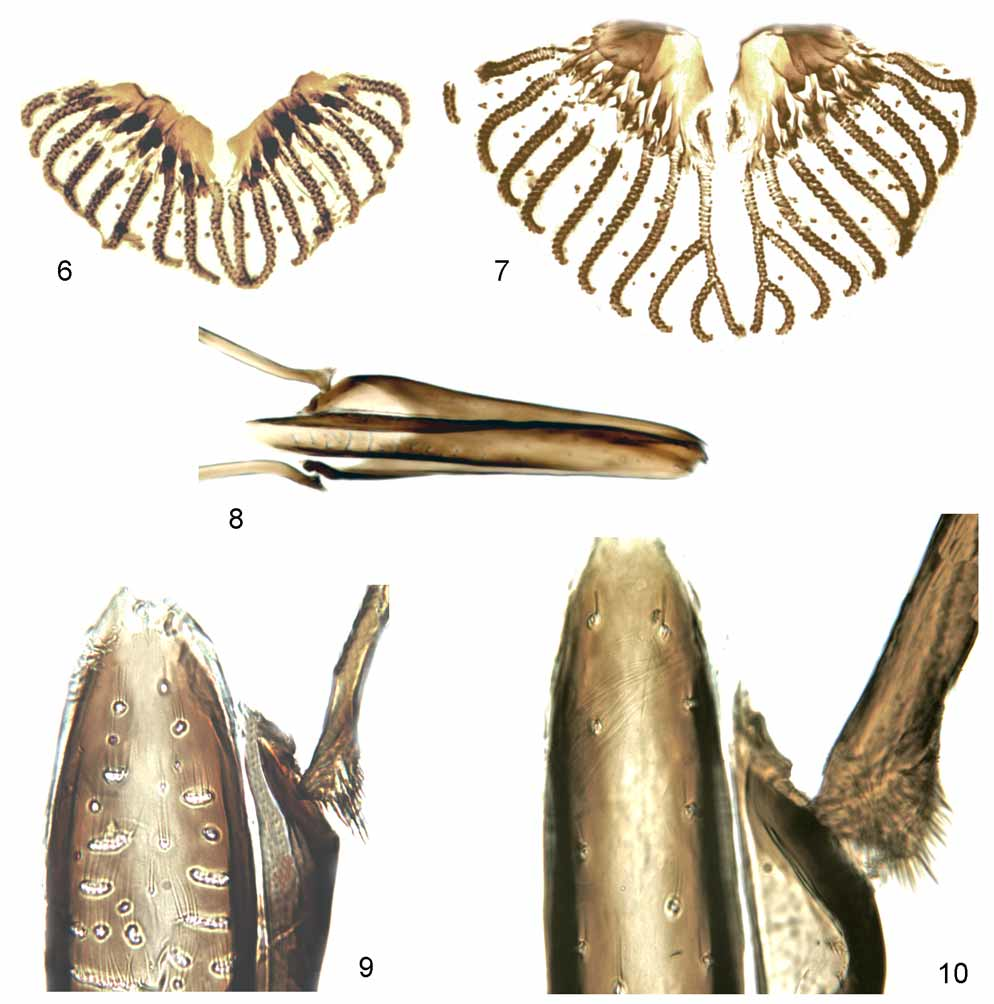

Upper frons usually narrower than diameter of anterior ocellus with linear, widely contiguous parafrontals. Frontal setae 3–4 pairs confined to lower half of frons. Pair of interfrontal setulae on middle of frons present or absent. Pair of minute fronto-orbital setulae often seen on upper part of frons. Genal setae arranged in single or multiple rows. Facial margin less projecting than frontal angle. Antenna unremarkable, with shortpubescent arista. Proboscis and palpus unremarkable except for relatively small labella ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES 6 – 10 ) with primary series of prestomal teeth moderately enlarged, tending to become uni-cuspid.

Distance between acrostichal rows anteriorly equal to or slightly shorter than distance between acrostichal and dorsocentral rows. Posterior posthumeral seta present. Prealar seta shorter than or of same length as posterior notopleural seta. Setulae at tip of scutellum stronger than hair-like setulae beneath tip of scutellum. Proepisternals 2–6; proepimerals 3–20, all setulose except for 1–2 setae. Katepisternals 1+2(–3). Prosternum bare, rarely with 1–3 pairs of marginal setulae. Vein C on dorsal and ventral surfaces extensively setulose or these surfaces in part or entirely bare. Lower calypter subequal to or smaller than upper calypter.

Fore tibia with 0–1 ad and 0–2 pv, apically with 1 d and 1 pv seta. Mid femur with a few short av setae basally and several longish pv setae on basal half that tend to stand in multiple rows basally. Mid tibia with 0– 1 ad, 1 pd and 1–4 p setae. Hind femur with complete row of av setae and a row of pv setae that may be complete or fall short of distal third to half. Hind tibia with 1 av, 2–3 ad and 2 pd setae, without any short setae on p–pv surfaces and without apical pv seta.

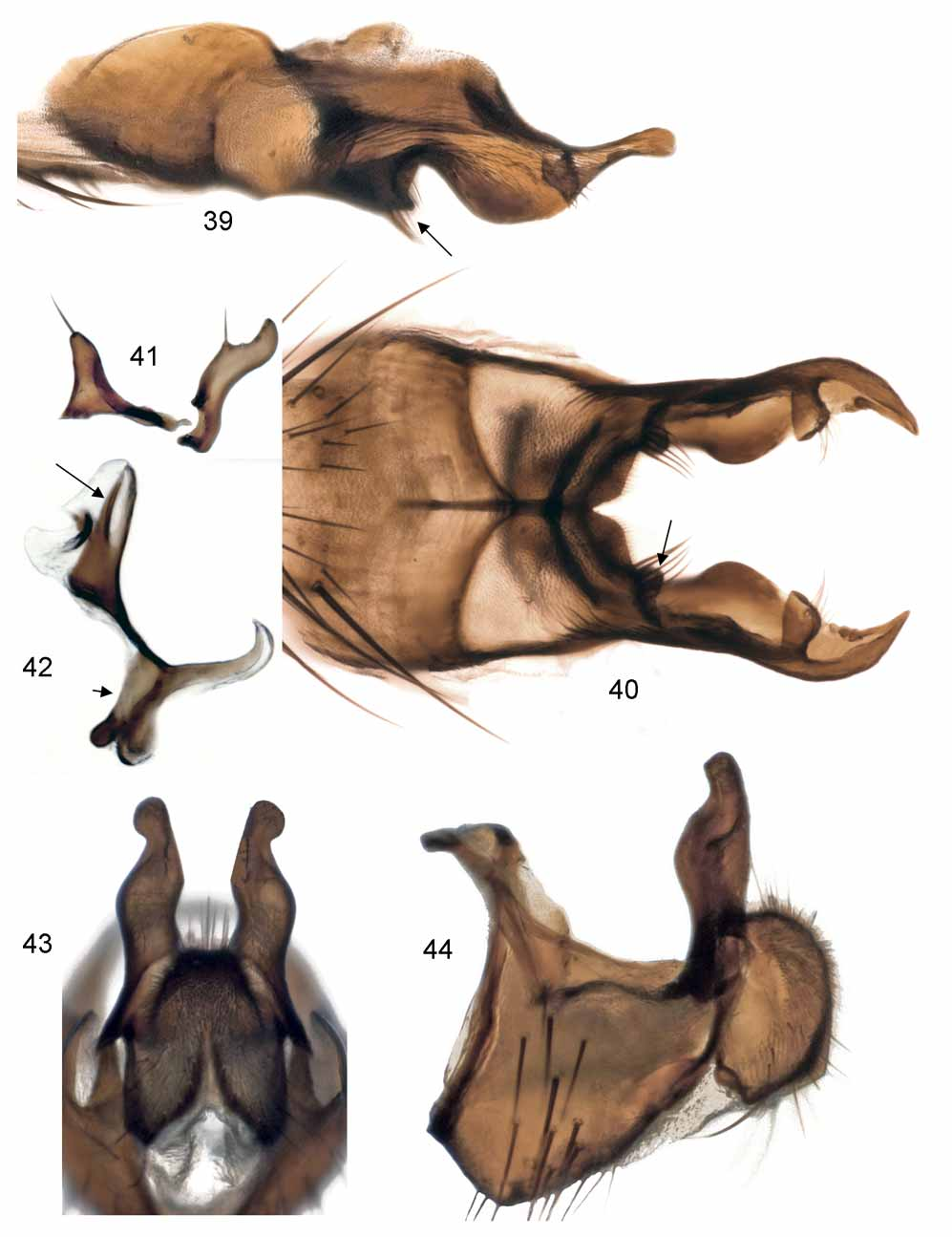

Abdomen slender to very slender, parallel-sided, depressed except more or less thickened on caudal segments. Tergites II–V with hind marginal but no discal setae. Tergite VI bare, sometimes very short and fused together with syntergosternite. Sternite V deeply incised at hind margin, forming a pair of posterior, subvertical lobes; each lobe possessing a more or less prominent bare angular lamella subdistally (e.g., Figs. 17 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , 24 View FIGURES 23 – 28 , 34 View FIGURES 34 – 38 ) that in some species (e.g., Figs. 39 View FIGURES 39 – 44 , 45 View FIGURE 45 , 69 View FIGURES 69 – 74 ) surpasses setose apex. In many species the setose apex of the posterior lobes of sternite V is uniquely tranformed into a small, articulated, inwardly directed, digitiform appendage more or less concealed from beneath by lamella (e.g., Figs. 40 View FIGURES 39 – 44 , 51 View FIGURES 50 – 53 , 70 View FIGURES 69 – 74 ). Cerci (e.g., Figs. 19, 20 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , 37, 38 View FIGURES 34 – 38 ) forming a convex, cordiform structure without a freely projecting apex between surstyli. Surstyli (e.g., Figs. 19, 20 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , 37, 38 View FIGURES 34 – 38 ) simplified, with usual meso-distal incision merely retained as a concave field on inner distal part delimited basally by a tiny knob. Gonites (e.g., Figs. 22 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , 28 View FIGURES 23 – 28 , 41 View FIGURES 39 – 44 ) subequal; pregonite with 0–1 submedian setula and 1 to several apical setulae; postgonite with 1 submedian setula. Phallus ( Figs. 42 View FIGURES 39 – 44 , 74 View FIGURES 69 – 74 ) with a club-shaped distiphallus supporting an acrophallic sclerite and smooth paraphallic processes.

Female. Cuticle more variable in colour than in male in as much as anterior parts of head (including parafacials, face and genae), postpronotal calli and rarely even scutellum and tarsi may be reddish to yellow ochre. Otherwise wholly dark species always orange red to yellow on lower part of frontal vitta. Dusting of head and body tends to be lighter greyish than in conspecific males and with darker striping faded on dorsum of thorax and abdomen.

Parafrontals always separated by wide frontal vitta with 1 pair of crossed interfrontal setae, on upper half with 2 reclinate and 1 proclinate pairs of fronto-orbital setae, on lower half with 2–3 pairs of inclined frontal setae. Antennal postpedicel sometimes enlarged and fully extended to margin of face. Palpus sometimes enlarged ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ), exceeding length of haustellum and/or strikingly expanded apically. Setation of legs as in male except for fewer and shorter av and pv setae on mid and hind femora. Abdomen broader, caudally tapering. Setae at hind margins of tergites II-V shorter, decumbent.

Oviscapt ( Figs. 11–15 View FIGURES 11 – 15 ) medium long, slender, tergites VI–VIII and sternites VI–VII extensively membranized, spiracles VI–VII opening close together at hind corners of tergite VI. Epiproct with several setae apically; hypoproct large, pubescent and abundantly setose. Cerci distally freely projecting, subcylindrical, abundantly setose, at apex with one particularly long seta. Three blackish spermathecae small, subglobular, with transverse wrinkles on surface.

Taxonomic history. The present concept of the genus Paradelia Ringdahl was first proposed by Michelsen (1985) and has the following background: Ringdahl (1933a) established Paradelia , as a new subgenus of Hylemyia , for the species Pegomyia lundbeckii Ringdahl. Ringdahl (1938) subsequently proposed Pegomyiella , as a new subgenus of Pegomyia , for the species Anthomyza lunatifrons Zetterstedt. Much later, Ringdahl (1959) upgraded Paradelia and Pegomyiella to genera and proposed the new genus Pseudonupedia for Anthomyia intersecta Meigen and six other species sharing some structural peculiarities of the male sternite V.

Huckett (1965) synonymized Pegomyiella Ringdahl with Pegomya , while he ( Huckett 1971) maintained Pseudonupedia Ringdahl as a subgenus of Pegomya . In his Palaearctic monograph on Anthomyiidae, Hennig (1972) treated Paradelia and Pseudonupedia as valid genera, but synonymized Pegomyiella with Paradelia without much argument other than mentioning that the two species involved appeared to be closely related to each other and to Pseudonupedia based on a similar phallus structure.

It was the structure of the male sternite V that convinced me that Hennig’s concept of Paradelia is paraphyletic in terms of Pseudonupedia and should either be narrowed or expanded to embrace both taxa. I preferred the latter solution ( Michelsen 1985) that was also adopted for the Nearctic monograph on Anthomyiidae by Griffiths (1987). However, Chinese dipterists ( Fan et al. 1988; Wei et al. 1999) have maintained Hennig’s classification by still keeping Paradelia and Pseudonupedia as separate genera.

Monophyly and outgroup relationships. Species of Paradelia are small to medium-sized, muscoid flies

with “typical” anthomyiid facies and only 2 pd submedian setae on hind tibia. The monophyly of Paradelia is

supported by the following presumed autapomorphies:

1. Labral food canal towards base with alveoles of gustatory sensilla merged into more or less transverse, bacilliform clusters ( Figs. 8, 9 View FIGURES 6 – 10 ). In other anthomyiid genera examined so far these labral sensilla arise from isolated alveoles ( Fig. 10 View FIGURES 6 – 10 ).

2. Male sternite V with a bare angular lamella arising from about mid-length of inner margin of posterior lobes (e.g., Figs. 24 View FIGURES 23 – 28 , 34, 35 View FIGURES 34 – 38 , arrow). This character assumes that the small, angular projection arising from the posterior lobes of sternite V in Paradelia lunatifrons ( Figs. 17, 18 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , short arrow) is homologous with the more elaborate lamella seen in other species of Paradelia .

3. Subepandrial sclerites ( Fig. 21 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , long arrow) posteriorly firmly connected to ventral bases of surstyli. Plesiomorphically the subepandrial sclerites articulate freely against the surstyli, as is seen in Pegomya and allied genera. It should be cautioned though, that the apomorphic state has certainly been attained through homoplasy in other lineages of Anthomyiidae .

4. As a plesiomorphy of Anthomyiidae — or at least in a major section of the family that also includes

Paradelia — small articulatory sclerites are inserted between latero-basal margins of surstyli and the

epandrium. These sclerites are in Paradelia basally inseparable from the epandrium (e.g., Fig. 38 View FIGURES 34 – 38 , arrow),

or ( P. lunatifrons only) rather reduced and even distally firmly attached to surstyli ( Figs. 20, 21 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , short

arrow). – Discrete articulatory sclerites are present in all the genera believed to stand closest to Paradelia ,

e.g., Pegomya , Eutrichota Loew and Alliopsis Schnabl & Dziedzicki.

Many species of Paradelia are easily confused with species of the large, diverse genus Pegomya , especially if they have setulae on the ventral surface of wing vein C. Paradelia are in the male sex separable from Pegomya by the simpler structure of the surstyli without ventro-basal and meso-basal processes as found in Pegomya (cf. Michelsen 2006a). Female Paradelia are in most cases separable from female Pegomya by their slender cerci with long, free apices bearing long tactile setae. As discussed by Michelsen (2006a), this presumably plesiomorphic condition has in Pegomya only been retained in the few species assigned to the P. testacea and P. ruficeps species groups.

It has been argued that the overall similarity between species of Paradelia and Pegomya is based on symplesiomorphy. As pointed out by Hennig (1976) and supported by Griffiths (1987), there exists more substantial evidence for a closest relationship between Paradelia and the genus Alliopsis (s. lat., including Paraprosalpia Villeneuve , Circia Malloch and Sinoprosa Qian & Fan ). The support for such a relationship concerns details of the mouth parts and male terminalia and may be summarized as follows:

1. Prementum ( Fig. 2 View FIGURES 1 – 5 ) piceous to black, with a strong shine due to absence of dusting.

2. Labella ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES 6 – 10 ) proportionately small, indicated by the lack of furcations of the posterior pseudotracheae. 3. Prestomal teeth in first row ( Fig. 6 View FIGURES 6 – 10 ) enlarged, tending to be uni-cuspid; subsequent teeth rows weak to

obsolete. The enlargement of the prestomal teeth is most pronounced in species of Alliopsis in which the

adults of both sexes are predacious on other insects (see below).

4. The presence of a more or less narrow and deep incision meso-distally on the male surstyli is so wide-

spread among Anthomyiidae that it probably belongs to the ground plan of the family. In Paradelia the

meso-distal incision (e.g., Fig. 20 View FIGURES 16 – 22 , long arrow) on surstyli is reduced, only retained as a more or less well-

defined concave field delimited basally by a small hump. Similar conditions are seen in Alliopsis . 5. Anterior sclerotized closure of basiphallus ( Fig. 42 View FIGURES 39 – 44 , short arrow) narrow and weak.

6. Distiphallus with paraphallic processes ( Fig. 42 View FIGURES 39 – 44 , long arrow) simple, devoid of any denticles or serrations.

Griffiths (1987) added the raised, sharp-edged, and sparsely setose inner margin of the posterior lobes of the male sternite V as a probable synapomorphy for Paradelia and Alliopsis . That supposition requires, however, that the ‘fleshy’ and abundantly setose posterior lobes of sternite V in the Alliopsis glacialis (Zetterstedt) species-group has been attained secondarily, which I find hard to believe.

The above list of characters in support of a closest relationship between Paradelia and Alliopsis may seem impressive, but taken individually none of the characters is very persuasive. The two genera further have very different life habits and ecological preferences. Most species of Alliopsis are “terrestrial” and more or less hygrophilous, often strongly depending on wetlands or littoral zones at running or standing waters for larval development. The adults feed regularly on live prey such as soft-bodied, adult or immature nematocerous Diptera . Species of Paradelia are on the contrary aerial and mesophilous, occupying both forested areas and open meadows. No observations have so far suggested that species of Paradelia share the predatory habits of Alliopsis .

As the above text implies, I am not fully convinced about the idea of a closest relationship between Paradelia and Alliopsis . Fortunately, it can be expected that the present, morphology-based hypothesis will soon undergo testing of new and independent evidence based on molecular data.

Species relationships. Griffiths (1987) analyzed the evolution of adult characters in Paradelia which gave support to the following three basic lineages: subgenus Pegomyiella [= P. lunatifrons ] + ( P. lundbeckii section + P. intersecta section [= subgenus Paradelia ]), a branching pattern that incidentally agrees with the taxa recognized by Ringdahl (1959) on the basis of a smaller, regional fauna: Pegomyiella , Paradelia and Pseudonupedia . The different, well supported monophyletic entities that Griffiths (1987) recognized within the present genus Paradelia are in the following all treated as informal groups in order to keep formal nomenclature as simple as possible [Griffiths’ names for the corresponding groups are given in brackets]:

Paradelia lunatifrons section [subgenus Pegomyiella ]

Paradelia intersecta section [subgenus Paradelia ]

Paradelia lundbeckii subsection [ lundbeckii section]

Paradelia intersecta subsection [ intersecta section]

Paradelia intersecta infrasection [ intersecta subsection] Paradelia intersecta species group [ intersecta superspecies]

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Paradelia Ringdahl

| Michelsen, Verner 2007 |

Pseudonupedia

| Huckett 1971: 76 |

| Ringdahl 1959: 292 |

Pegomyiella

| Ringdahl 1938: 191 |

Paradelia

| Ringdahl 1933: 33 |